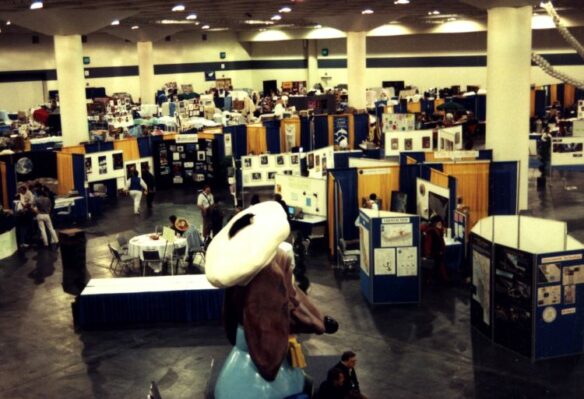

Worldcon Wayback Machine Introduction: Thirty years ago this weekend ConFrancisco, the 1993 World Science Fiction Convention, was held in San Francisco, California. I thought it would fun to compile a day-by-day recreation drawing on the report I ran in File 770, Evelyn Leeper’s con report on Fanac.org (used with permission), and the contributions of others. Here is the fourth daily installment.

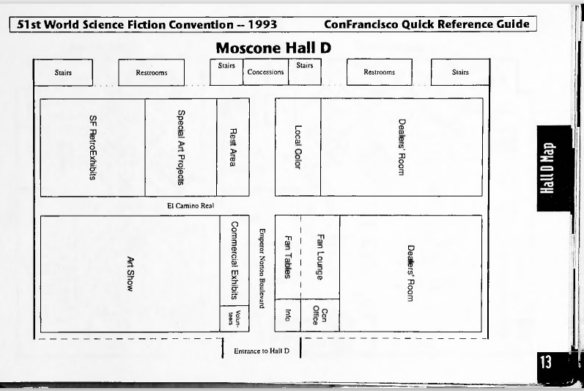

The Worldcon was held in the Moscone Convention Center, ANA Hotel, Parc Fifty Five, and Nikko Hotel.

Fans woke up Sunday morning and reached for a copy of the daily newzine to find out what they’d done the night before.

[Kurt Baty & Scott Bobo] Saturday Night Party Roundup. (Excerpted from The Norton Reader #8) Round 3! And we were greeted in the San Antonio in 97 suite by a Brad Foster party announcement drawn on erasable(!) board; we thought this primo in party decor.

Our now sizable entourage trooped to the top o’ the Parc to bridge the Bridge Publications party, where we watched Wanna the temple slave dance teasingly before the heroic proportions of the costume Battlefield Earth cutout. She was a hall costume winner and celebrating.

Now in a prehistoric mood, we entered the a WesterCon’94/95 suite and admired the in-progress Crayola crayon wall mural a la early “Con”ozoic.

In Atlanta in 98 we found a punch packed with peach, both with and without C2,H3OH (as they put it). Now in a jolly roger mood, we decided to pirate some rum and Coke from the friendly Baltimore in ’98 crew. Yo-he-ho.

Fans must have been hungry last night, as St. Louis in ‘97 set out a new set of bittersweet, milk and white chocolate bars (has it been 60 pounds already? Watch those hips! Morning aerobics, anyone?) Healthniks who were able to look beyond the chocolate agreed their veggie platter balanced the caloric orgy.

We backtracked to the Winnipeg/Glasgow Presidential suite for a fabulous blowout. Our fave fish cheeks chef, Hans Schweitzer (he’s all the rage now, you know, and a veritable fixture at WorldCons) sauteed cheeks (fish) for us. We consequently awarded him one of our Bheer pins for his chef’s sash. We satisfied our thirst with Glasgow’s inimitable and very Smooooth whiskeys.

We discovered smoked buffalo in the Coenobium party at Sophie’s urging. It was totally bison – and that’s no beef. We chilled out at the Cryonics party while discussing whole-body vs. head options. Really. Frankly, we’re partial to feet when it comes to party-hopping. Fetish, anyone?

The Space Access group gave us some space to breathe while we took a moment to catch our breath (great videos later – ed). In Norway (the party) we tested the varieties of aquavit (both above and below the equator) and were assured that a real Norweigan can tell the difference. Ja, sure.

Our Russian friends had their first beer (root, that is) in the Arisia suite. They decided they prefer the real thing, although we’re partial to A&W.

By this time, we had worked up a sweat so were delighted to discover the Sno-Cone machine in the Silicon party festooned with blue and orange crepe paper and balloons. What party review would be complete without a mention of the Con Suite? They were holding their own at 11:50, largely because of the spillover from the masquerade and the upbound fan jam (and the “Ice Cream of the Future” was pretty weird, too – ed).

We wandered overto the midnight Cult seance, but the only spirits we saw being raised were alcoholic. Going back to the top o’ the Parc, we returned to San Antonio (the suite) to hear that “some varmints had rustled the cacti!” Marshal Lisa later apprehended the desperados. We intend to give her a medal (Bheer!) for valor in defense of parties.

By 2:30, the AussieCon bid party was still strong; we took a moment to admire their edible monster table decoration. Amazing what can be done with a cantaloupe…and a little wax. Norway and Australia both performed admirably, but we decided to award the now well-experienced hosts of Winnipeg/Glasgow the Saturday “Party of the Night” Award. (Polite applause, please.)

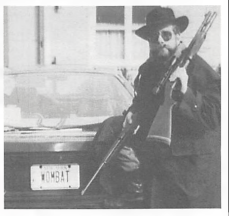

[Mike Glyer] Panel: Smoke-Filled Back Room. (Sunday 10:00 a.m.) [Panelists:] Arlan Andrews, Ben Bova, jan howard finder, Steve Gillett, Mike Glyer, Hugh Gregory, Bradford Lyau, Richard Lynch, Charles Sheffield] [Topic:] “Our Honored Guest jan howard finder presents his shadow cabinet as a presidential “candidate” who is pro-space. WOMBAT For President!”

Among the GoH program items was a panel moderated by jan howard finder, who took the role of a presidential candidate surrounded by a cabinet composed of pros and fans called to answer the question: “What would be your initial program to get the country moving in the right direction which involves the space program and space?” His romantic call for renewed space exploration came paired with a practical understanding that voters would need to be motivated to pay for any proposal.

The idea never really worked because finder did nothing to keep the majority of panelists, Steve Gillett, Ben Bova, Brad Lyau, and Hugh Gregory, from changing ground to something they knew about. The panel became a 2-hour symposium on SSTO (single-stage-to-orbit) spacecraft. Two other writers made worthy but futile attempts to pull the others back on track, Arlan Andrews, possibly the only panelist who had worked for a presidential administration, and Charles Sheffield, who illustrated his remarkable insights with cleverly expressed lines like: “The soil conservation bureau long ago realized that mud is a national treasure.”

[Evelyn C. Leeper] Panel: Northern California in SF/F (Sunday, 10:00 AM) [Panelists:] David Bratman (m), Don Herron, Pat Murphy, Diana L. Paxson [Topic:] “The where and why of using real world locations in speculative fiction, with examples drawn from the world right outside the convention’s doors”

I arrived a little late to this, and missed the beginning, but Paxson was comparing using northern California to using Britain as an inspiration. In Britain, she said, there are a lot of structures, ancient and not so ancient, that can be used, and northern California lacks those. But northern California does have legends, and those can take the place of buildings. One of the stories set in the area that she talked about was Ursula K. LeGuin’s Always Coming Home, set in the Napa Valley in the far future after an earthquake has changed the contours of the land. To get the geography right, LeGuin had a cartographer friend of hers (George Hirsch) construct a three dimensional map of the area, then tilt the appropriate sections and flood it with water to see what the new shapes of the bodies of land and water would look like.

Many authors have used San Francisco as a setting. But do they really have that “sense of place” that is so important? Philip K. Dick had it in Martian Time-Slip and other stories, according to the panelists, but Dean R. Koontz’s Shattered (written under the pen name K. R. Dwyer) made it obvious that Koontz had never been in San Francisco. The Net by Loren J. MacGregor did a good job of describing the bars south of Market Street. Perhaps the classic use of San Francisco in science fiction/fantasy is Fritz Leiber’s Our Lady of Darkness, though Pat Murphy’s own The City, Not Long After certainly ranks up there.

Regarding her work, Murphy said that her work in the Exploratorium trained her to observe and “see beyond the surface,” and that is what lets her see the potentials of settings. Someone apparently mapped out all the places mentioned in The City, Not Long After, though Murphy says that the map would probably be a disappointment to try to follow; for example, the vacant lot where the refrigerator sculpture is in the book has no such sculpture in real life (yet!). Regarding this, one of the joys I find is walking around a new place and finding the settings that were described in literature or even other travelogues. And I am not alone–when we were on a boat of about ninety passengers in the Galapagos Islands a few years ago, at least five of us were reading Galapagos by Kurt Vonnegut. Murphy also warned that she and other authors often change some details (such as house numbers) to protect the people who live in the houses. You can claim that room 1247 of the Marriott is haunted– it’s a public building and “fair game.” But if you claim that 1726 Fairlawn Drive is haunted, the people who live there may not like the reputation their house gets. (Does the name “Amityville” ring a bell?)

And of course this sort of desire has spawned the “literary tour” movement, which has two subcategories: tours that visit places mentioned in books, and tours that visit places connected with the authors of these books. Some tours combine both, perhaps showing you where Dashiell Hammett lived and also the places he wrote about. The places connected with authors are often a disappointment–someone said that you go to some house where a famous author wrote his first novel, and you discover that it’s being inhabited now by a Vietnamese family who can’t understand why you are standing on the street taking pictures of their house. (It’s sort of like going back to your childhood home years later. People think you’re casing the joint.)

[Mark R. Leeper] Panel: Getting Around the Solar System (Sunday, 2:00 PM) [Panelists:] Jim Baen, Suzanne Casement, William S. Higgins, Gentry Lee, Jonathan V. Post (m) [Topic:] “What will life be like when we’re not confined to Terra?”

The panel started with the members introducing themselves. Gentry Lee was director of scientific analysis on the Viking Mission and a co-author with Arthur C. Clarke. Bill Higgins is from Fermi Labs. (Personal note: He also put together the science program at Chicon which in my humble opinion was the best at any Worldcon I have ever attended.) Jon Post works on research into nanotechnology, worked on the Magellan space mission and also Voyager 2. Suzanne Casement is a graduate student at UCLA. (In general Lee is more an advocate of unmanned robotic information[1]gathering missions. Higgins, active in the National Space Society, wants man to become a space[1]faring race and would much rather see manned missions than mechanical proxies.)

Post suggested that the first half of the discussion concentrate on what is currently being done in space and what will be done for the next thirty to fifty years. Later they would get to longer term. Lee thought that on the short term the emphasis would be on unmanned missions mostly. Manned missions would be mostly be “Antarctica-type” colonies. With robots we can do a lot more. Decisions have to be made who will pay for space exploration where are we going to go. The Challenger disaster was a real tragedy for the program and now engineering foul-ups, like on the recent Mars mission are making things worse for funding. The Mars Observer was an important lynch-pin and would lead to a lot of future planning. Losing it will cause a huge problem in deciding on new missions needed. We are now going for smaller craft that will have smaller ranges.

Post asked what major changes did members see coming. Higgins said there will be more of a push from the NSS to make hardware that is small and smart. He suggested that there would also be a look at other methods of propulsion. We still seem to be using the same old chemical propulsion rockets and we are nowhere near trying some other propulsion. He expanded on the National Space Society’s position saying that they are working to create a space-faring civilization and that they will really push for anything that will forward that goal. Particularly favored are plans to do prospecting on the moon and asteroids. However, the NSS is not particularly pushing for the missions to map Venus since it seems unlikely that Venus will be a near-term source of resources.

Casement said that in November a wide-field camera will be put in the shuttle for the Hubble telescope. It will be used to look a the planets and design missions. However the problem with the Hubble is that its designs were frozen about ten years ago in order to be able to build it and it would be much more effective with up-to-date technology.

From there the discussion moved to Post’s work experiences. He talked about his work on the Titan 34D. They worked to improve designs on that. His group made basic improvements to the shuttle like using multicolor displays. They also worked on error detection to predict component failure. Among the things that he worked on was a proposal for advanced launch systems including single-stage to orbit. One scheme he proposed included using a huge ground-based laser to power a craft. However, he feels that even if there is research into other propulsions, it will be a long time before rockets have much competition for sending things into orbit. He did discuss using solar sails once equipment is in space. Also he said he had invented a magnetic sail using magnetic field to push huge loop of wire. One of the long-term proposals was to build a craft out of solid hydrogen, cryogenically frozen, so that when it gets to its destination the entire structure could be used as fuel. If there is ice at Mercury’s poles, he suggests that we purify the water and use the poles as a fuel depot near the sun.

Lee considered all the possibilities and said we are in a sort of Burgess Shale point in technology. In the period of the Burgess Shale being formed there were many and very diverse life-forms. Some seem very strange to modern eyes. Evolution pared them down to a few successful types of life-forms and the rest died out. Technology is at a similar stage when there are many baroque ideas for how to solve problems of space travel. The vast majority of these will be discarded. With all the different possibilities for powering cars we have basically one kind of car, one powered with the petroleum[1]fueled internal combustion engine. We have basically one kind of rocket, and we will find which of the current weird ideas for space travel are the best of the lot and the rest will all be discarded. There will be one or two space transportation systems in the future. There will be one or two kinds of propulsion. Lee thinks that in the future we will be seeing primarily robot-control in space in the future. People will fly but not be doing the driving. He sees no compelling reason to put people into space.

Higgins responded with a defense of placing people into space. He said that we are in a time of rapid technological evolution. There will come a time when it will be cheaper and more convenient than today to send people into space. At that point far more people will want to travel in space. Scientists would like to be near what they study. And the biggest product from space will be information. A lot of people on earth will want to learn about new places.

Post asked the panel what is it that calls to us from beyond the solar system and how will we answer that call.

Casement said that people have an interest in finding other solar systems. JPL is already investing in interstellar exploration. But if there is an explorer mission to stars it will take a long time to get data back. Closer to Earth there is Voyager and Pioneer sending data back about more distant destinations and they are still finding interesting things.

Post observed that Gentry Lee sees no compelling reason to send people to the stars, but that does not mean that people will want to go anyway. Post asked what it is that pushes people. Why did people in the United States head west? Most were not looking to get rich, they were fleeing a society they could not stand.

Lee countered that they could breathe in California–they will not be able to do that in space.

Post asked if price came down, would people go? In the days of the Western expansion the cost of a covered wagon and the provisions to go west would be about $300,000 in modern money. If the cost comes down to $300,000 to go to Mars, he expects people will go. And everything said in this panel assumes nothing big is going to happen. If we find proof of alien intelligence, everything changes. If things get so bad on Earth that we will have to escape that will also push us into space.

Lee did not envision a massive move into space. He polled the audience as to how many people they thought would be living off Earth in 500 years. Most said they expected the number to be more then a million.

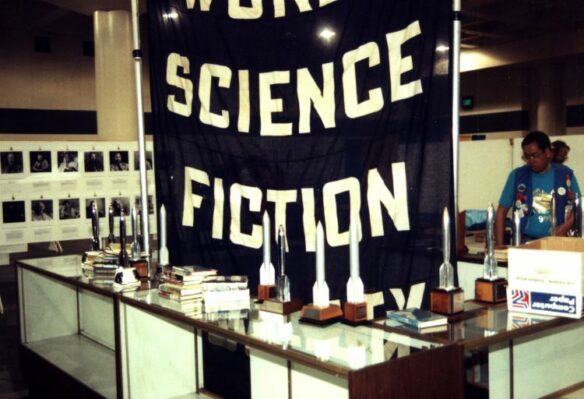

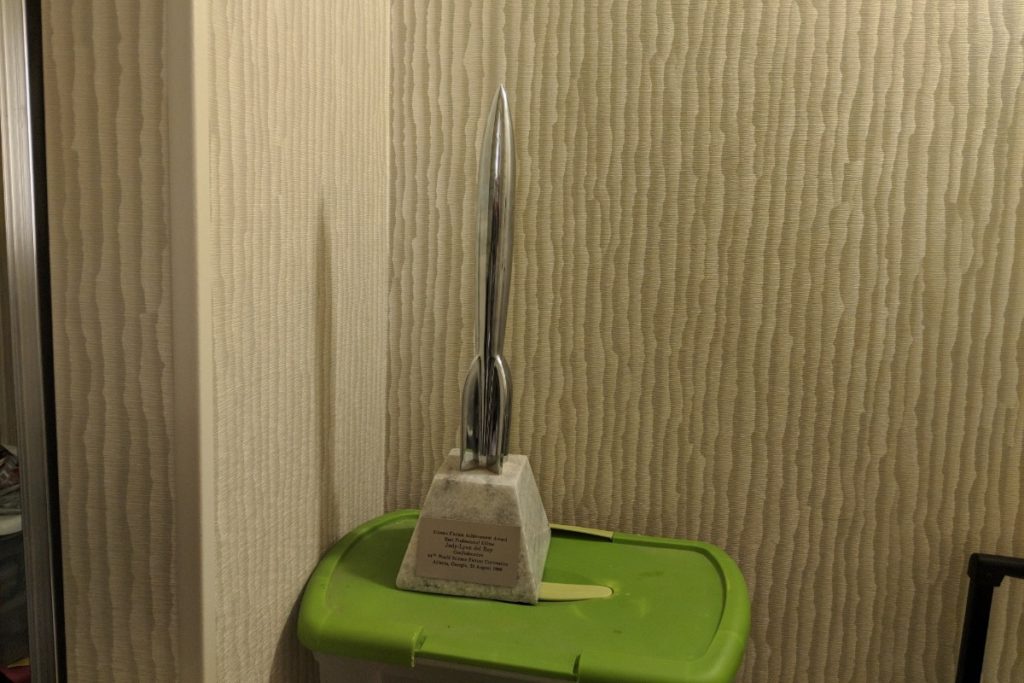

[Mike Glyer] A SMOFfish Controversy: Should Fans See The Hugo Base Before the Awards Are Given? In 1988, NOLAcon II chair John Guidry passionately believed that the Hugo base should be a beautiful work of art, and in 1992 artist Phil Tortorici fulfilled a similar vision for MagiCon.

ConFrancisco’s bases were being produced by artist Arlin Robbins and expecting something beautiful, the committee wondered if a copy of the base might be displayed in the Hugo Awards exhibit at the start of the con.

When the committee asked this year’s nominees for an opinion they found three schools of thought, by far the largest made up of those completely apathetic about the subject. Since the splinter group opposing early display of ConFrancisco’s Hugo base included the woman running the Hugo ceremony and the man in charge of the Hugo exhibit, ConFrancisco kept the traditional award-night unveiling.

Remember that Worldcons did not have a Hugo history exhibit before 1989. Most people never saw a Hugo close-up unless they bumped into a winner in the hallway. Then again, almost all Hugos given before 1984 were mounted on wooden bases and looked like glorified bowling trophies. There wasn’t anything about them that deserved an audience, and no special reason to be curious about their appearance. One glorious exception was Tim Kirk’s ceramic dragon base for the 1976 Hugos.

Since 1984 almost all the committees have rejected the cliched wooden base in favor of original art or a base made of a unique material, like Australian rosewood or Georgia granite. The artistry of the Hugo base has become a convention’s voice in the ongoing dialogue about how to express the award’s meaning in physical form. Tony Lewis, like everyone else on the Noreascon 3 committee, was proud of Noreascon 3’s Hugo base, a design inspired by landmarks of the 1939 World’s Fair. During the con he guided me into an office to see one close-up. Twenty Art Deco Hugos were lined up on the table, an impressive sight. Jill Eastlake, responsible for the awards, decided not to object since the nameplates were covered with masking tape and I wasn’t going to be handling them. Yet I privately wondered if I was indecently peeping before the ceremony. Thinking now about that experience I realize that I reflexively responded to an aura of secrecy associated with the need to guard the Hugo winners’ name plaques until they have been properly announced; the concealment of the design has only been a coincidental byproduct of that security. Further, for most years before 1984 there was no special reason a committee would want to display its generic wooden base, and prior to 1989 there was no planned exhibit where the current-year Hugo might be shown.

I’m Spartacus! No, I’m Spartacus! Hugo nominees, presenters and guests were invited to a 7:00 p.m. Sunday reception behind the stage in the Esplanade Ballroom, and cautioned to arrive by 7:30 with an eye to an 8:00 starting time for the ceremony. Everyone who cooperated was rewarded with an extra wait of 45 minutes for a late start. There was time for many conspiracies to hatch while the nominees grew restless, munching cheese cubes and gourmet crackers. We began improvising our own amusements.

Andy Hooper noticed Martin Hoare, Langford’s perennial Hugo accepter, and suggested if Langford won, “Let’s all stand up and yell, ‘I’m Dave Langford! I’m Dave Langford!”‘

Dick and Nicki Lynch, Lan Laskowski, Leah and Dick Smith [remembering last year’s mixup] and I also pretended to agree that no matter who they announced for Best Fanzine we would stand in unison and ask, “Are you sure?”

Hugo nominees had been asked by the committee to come in formal attire. I chafed at the suggestion, but division chief Janet Wilson Anderson swayed me with her clever reply to my complaint: “We do want a certain ‘air’ for the Hugos. Tuxes by all means for those who like ’em. Fannish Formal is perfectly appropriate, however, for those ‘tux-phobic.’ I attended the Confederation Hugos as a representative of a Hugo nominee dressed in Irulan’s gold gown from the movie Dune, and at Chicon wore my Napoleonic Court gown. Such garb would also be fine here (though it probably isn’t quite your style.) Gary [Anderson] wore the Padishah Emperor’s Uniform and looked quite formal.”

Diana Pavlac eventually convinced me Denisen Fraser issued the “black tie” advisory out of a gracious sense of wanting to let people know what is appropriate rather than letting it come as a surprise that many nominees do, indeed, dress to the teeth.

So, Diana and I took a few moments before the awards to see how people responded to the committee’s advice. Many did dress formally. Those who dared to be different did it with flair, like Andy Porter in the robes of an Oxford University Doctor of Divinity. Joe Haldeman thanked the committee for allowing him to present Hugos in two categories and giving his tux the extra exposure.

When the guests were dispatched to reserved seats in the VIP section, Fraser was ready to set the wheels in motion. Kevin Standlee perched on a chair and relayed her briefing to the nominees about their order of march. Kevin’s many colorful ribbons covered him like the high priest’s breastplate.

Hugo base artist Arlin Robins was introduced, and waved a sample of her 1993 Hugo overhead. Robins’ octagonal Hugo base was decorated with pewter castings, a compass rose on top and reliefs of well-known sf figures on several sides, including Hugo Gernsback. The craftsmanship was not equal to the idea, for the metal did not take the facial features very well and the identities of the figures weren’t apparent without reading the names underneath.

At last, the nominees were formed up and paraded to their seats.

In the dusk at the edge of the stage I recognized Val Ontell’s voice. She asked if I could see her husband, Ron, standing beside the last seat on the far side and said to walk to him. Ron picked that very moment to leave, and not knowing whether it was part of the plan I kept after him like a runaway steer until Marjii Ellers circled in front of me and aimed me at my seat. For all the jokes I made about Noreascon 3, I wish I could march in to the gladiator’s theme from Ben-Hur once more…

Several pros, most notably, Patrick Nielsen Hayden (on GEnie), accused ConFrancisco of poor hospitality toward program participants in general and Hugo nominees in particular. “I have to wonder at ConFrancisco’s many ‘anti-perks.’ Program participants had the extra-special excitement of additional lines and complications to chase down. Hugo nominees were honored even more by being made to stand up in the wings for forty-five minutes, and made to miss the cool Delta Clipper video.

“In general, I think we could stand to lose this whole procession-of-nominees thing. It was goofy and embarrassing when Noreascon did it, but at least they pulled it off with organization and dispatch. …At ConFrancisco, we had the spectacle of nominees’ spouses standing around looking puzzled and out-of-sorts while their significant others were held captive in the wings. Further, nominees and their spouses had the even more extra-special honor of being unable to pick where they sat, or who they sat with.

“One suspects the whole thing is designed to lather the egos of the people stage-managing the spectacle, rather than to honor anyone or make it an entertaining experience for the audience.”

My personal reaction was quite different and completely subjective. The rest of my weekend was so hectic that I regarded the nominees’ reception to be an oasis of relaxation. I welcomed the opportunity to talk to long-time friends, including Martha Beck, who I otherwise would have missed altogether.

I Never Wrote SF for My Father: Toastmaster Guy Gavriel Kay engaged in byplay with the tech crew and confidently assured everyone he had things under control: there would be no repeat of last night’s problems because he had — a TV remote control. Out of Kay’s sight his every comment was sarcastically denied by verbal slides projected on a screen at the left of the stage.

Three non-Hugo awards were presented first.

The Japanese national convention’s Seiun Awards won by Americans were presented by Masamichi Osako, Takumi Shibano and Nozomi Tashiwaya. Best Novel went to Poul Anderson for Tau Zero in translation. Poul was the only winner present; two other winners were R.A. Lafferty, for a short story, and Daniel Keyes for a nonfiction book.

Forry Ackerman presented a richly-deserved Big Heart Award to Marjii Ellers.

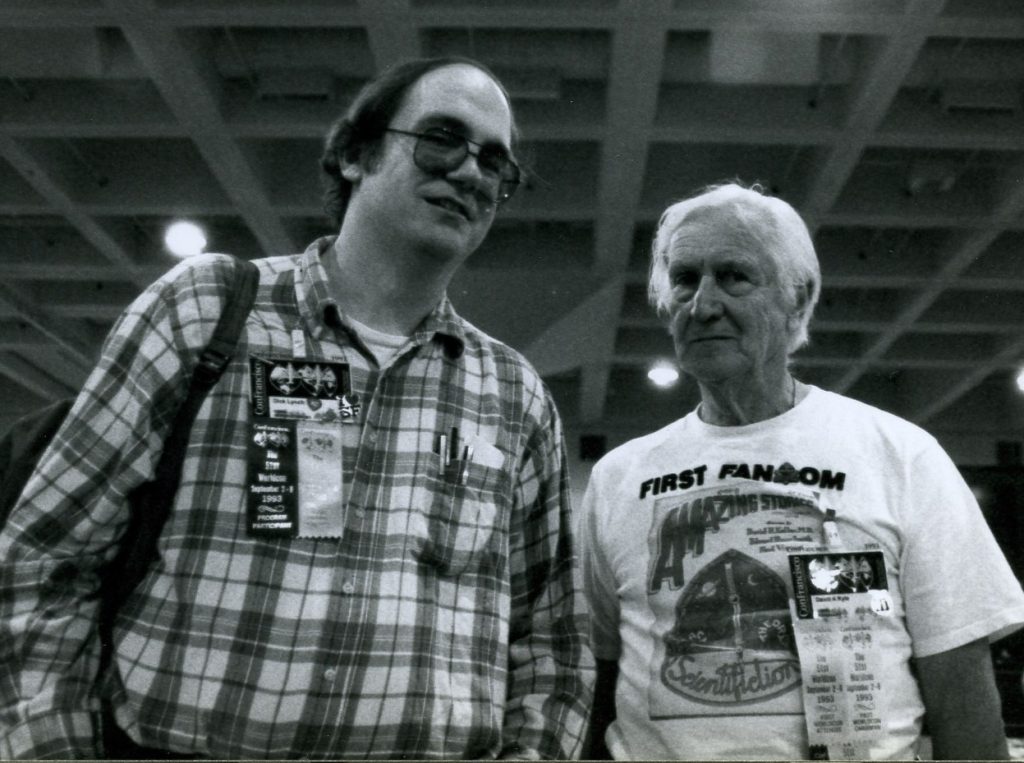

Dave Kyle came out and introduced Catherine Crook DeCamp, who presented the First Fandom Award to Ray Beam, turning the tables on the man who has given out that award so many times. Beam’s remarks closed, “Remember: if it wasn’t for our efforts, you wouldn’t be here tonight.”

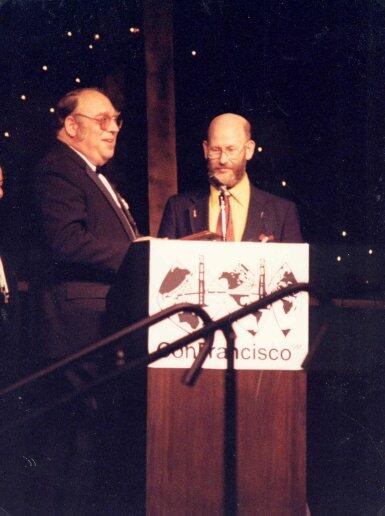

Chairman Dave Clark announced ConFrancisco had designated a Special Award based on its central theme of building international bridges, to Takumi Shibano. It was a big weekend for Takumi, also selected (together with his wife, Sachiko) as Fan Guest of Honor for L.A.con III in 1996.

Then Janet Wilson Anderson narrated an excellent retrospective of the Hugos composed of slides of old photos taken by Jay Kay Klein, trivia questions spanning the entire history of the award, and chronologically-ordered pictures of books or magazines containing Hugo-winning fiction. Janet and company’s lively and innovative approach made one forget that retrospectives have been done at the past several Hugo ceremonies.

Kevin Standlee, whose responsibilities included supervising Hugo administrators Seth Goldberg and Dave Bratman, engaged in a comic moment by declaring ConFrancisco had gone beyond Price Waterhouse to insure the secrecy of the results. “Security to the bridge,” ordered Kevin and a pair of Klingons came out carrying the award envelopes.

Between the delay and the time devoted to other awards, the first of the official awards, the John W. Campbell Award, was given at 9:47 p.m. The Campbell was won by Laura Resnick. As she was somewhere in the Kalahari region of Africa, her father accepted the plaque for her. Laura had already conquered the romance genre by the time she turned to science fiction: she also won an award for Best Romance Novel of the Year in 1993. Mike Resnick announced later, “My stud fee just doubled!”

In a departure from the usual, each Hugo presenter announced two winners. TAFF delegate Abi Frost gave out the Best Fanartist Hugo to Peggy Ranson, and the Best Fanwriter Hugo to Dave Langford’s proxy, Martin Hoare. Martin was sure when he phoned Dave in London a little later, Dave would answer, “You bastard, you woke me up this time last year, too!”

One of the con’s guests of honor, jan howard finder, presented the Best Fanzine Hugo to Mimosa, which won for the second year in a row. Amid the applause I heard Stu Shiffman yell out, “Bring back Nicki Lynch!” to compensate for my attributing that quote to him in my MagiCon report when he’d actually been in Seattle at the time. And who says fans aren’t timebinders… Then at the end of the ceremony Jay Kay Klein asked me for his subscription check back, “So I can give it to the fanzine that won.”

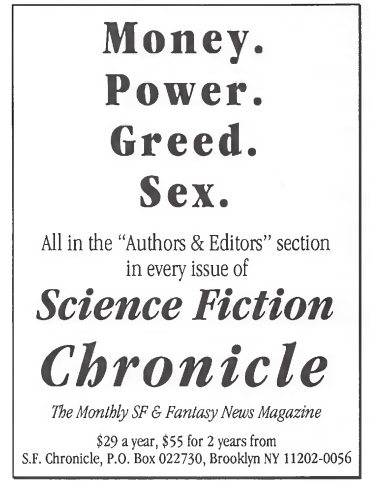

Finder also got to unleash the surprise of the night. When the Best Semiprozine Hugo went to Science Fiction Chronicle, a quarter of the audience gave a standing ovation. Andy Porter practically flew to the stage with his doctoral robes fluttering like wings. He declared, “These are not the robes of a Doctor of Divinity, but bless you all.” Locus had won the category the nine other years it had been given, and for four consecutive years before that won as Best Fanzine. (Andy Hooper asked, “Do you think Andy will have the new masthead cut by tonight?”)

Winners received the announcement cards along with their Hugos. Jeremy Bloom, of the daily newzine staff, reported the card listing SF Chronicle as Best Semiprozine added underneath in parentheses, “Really. Not Locus. No Kidding.”

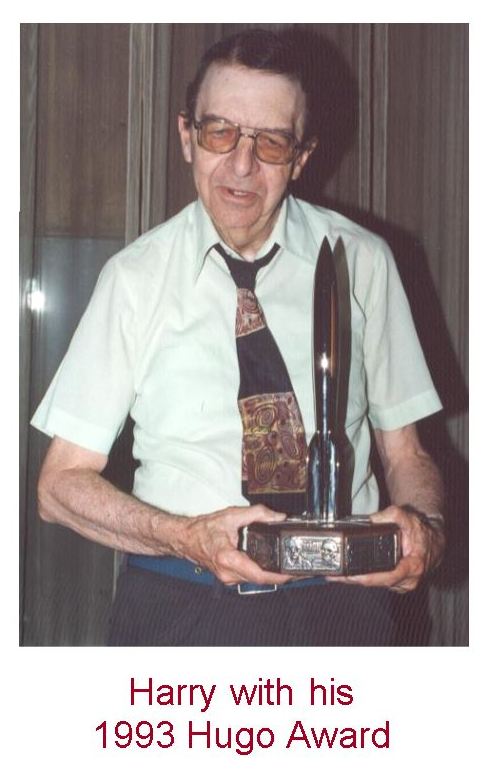

Tom Digby, also a con GoH, delivered the Best Nonfiction Book Hugo won by Harry Warner’s A Wealth of Fable, edited by Rich Lynch, to the publisher’s representative, Bruce Pelz. (The book had been published by SCIFI, the group responsible for L.A.cons II and III.)

Gardner Dozois, looking spiffy in his salt-and-pepper jacket, gray slacks and shoes of a color that instantly brought Ricardo Montalban to mind [“rich Corinthian leather”], took away another Best Pro Editor Hugo. GoH Alicia Austin handed out the two artist Hugos, to James Gurney for “Dinotopia” and to Don Maitz. Dead guest of honor, Mark Twain, bestowed a Hugo on “The Inner Light” episode of ST:TNG, accepted by Peter Lauritsen.

Presenter Joe Haldeman saddened to suddenly remember that, 25 years before, his wife had been here in California while he was in the battlefields of Vietnam with two weeks to go until their R&R rendezvous, one he never kept because he was seriously wounded and hospitalized. Joe recovered and made jokes about his tux, and handed out the first of Connie Willis’ two Hugos. Connie Willis got a big laugh in her thank-you speech for “Even the Queen” when she said she had complained to Gardner Dozois on winning the Nebula for it that she would now have to go home and tell people what it was about — and she didn’t know what to say. “Tell them it’s a period piece,” suggested Gardner.

Haldeman delivered another Hugo to Janet Kagan who emotionally thanked her mom “for reading me science fiction before I could read it for myself.”

GoH Larry Niven announced the final two Hugos. Lucius Shepard’s Best Novella was accepted by Gardner Dozois who admitted, “I’m not Lucius Shepard, but I play him on TV.” Then came the tie for Best Novel between Connie Willis’ Doomsday Book and Vernor Vinge’s A Fire Upon the Deep. In the past there have been nine ties for Hugo or Campbell awards, and this was the first tie in the Best Novel category since 1966, when Herbert’s Dune and Zelazny’s …And Call Me Conrad shared the Hugo.

Ray Pettis told this story showing how SF Chronicle’s win overshadowed every other result: “When I was riding up in the elevator at the ANA after the ceremony, someone got on at the Filk floor — I assume he saw the high proportion of fancy dress — and said, ‘Hugo’s over?’ <‘yes’> ‘Any news?’ Robert Silverberg’s first comment from the back of the elevator was ‘Andy Porter won; Locus didn’t.’ On a night when there was a tie for Best Novel, and Star Trek: The Next Generation won a Hugo, and women writers dominated the wins, the first comment is ‘Andy Porter won.'”

1993 HUGO AWARD WINNERS

Best Novel (tie)

- A Fire Upon the Deep by Vernor Vinge (Tor)

- Doomsday Book by Connie Willis (Bantam)

Best Novella

- “Barnacle Bill the Spacer” by Lucius Shepard (Asimov’s, July 1992)

Best Novelette

- “The Nutcracker Coup” by Janet Kagan (Asimov’s, December 1992)

Best Short Story

- “Even the Queen” by Connie Willis (Asimov’s, April 1992)

Best Non-Fiction Book

- A Wealth of Fable: An informal history of science fiction fandom in the 1950s by Harry Warner, Jr. (SCIFI Press)

Best Dramatic Presentation

- “The Inner Light” (Star Trek: The Next Generation) (Paramount Television)

Best Professional Editor

- Gardner Dozois

Best Professional Artist

- Don Maitz

Best Original Artwork

- Dinotopia by James Gurney (Turner)

Best Semi-Prozine

- Science Fiction Chronicle, edited by Andrew Porter

Best Fanzine

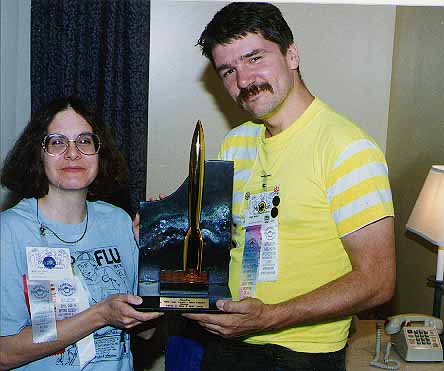

- Mimosa, edited by Dick and Nicki Lynch

Best Fan Writer

- Dave Langford

Best Fan Artist

- Peggy Ranson

John W. Campbell Award for Best New Science Fiction Writer of 1991-1992

- Laura Resnick

Special Committee Award

- Takumi Shibano, “For building bridges between cultures and nations to advance science fiction and fantasy”

ConFrancisco received 841 valid ballots for the awards. They were counted and verified by the ConFrancisco Hugo Administrators, David Bratman and Seth Goldberg, with the assistance of a computer program developed by Jeffrey L. Copeland.