Monday, September 4, 1989 at Noreascon Three. Final installment of my reminiscences about the once-in-a-generation convention that took place 25 years ago this week.

This is really only a postscript. My work schedule made it necessary for me to fly home and miss the last day of Noreascon 3. Yet luck was with me. I still picked up a good story while waiting for the plane.

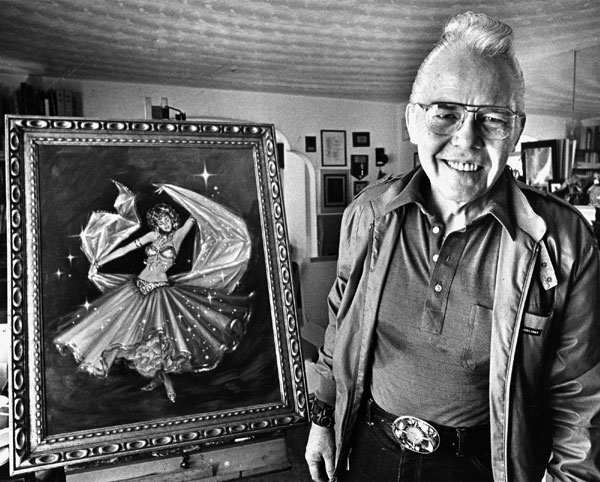

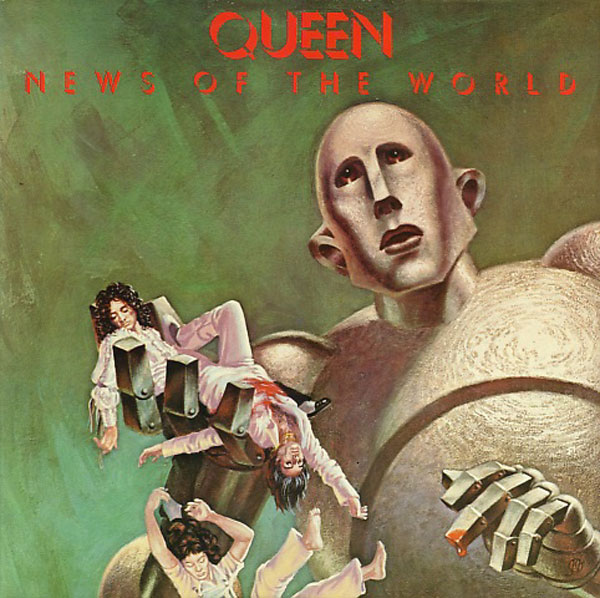

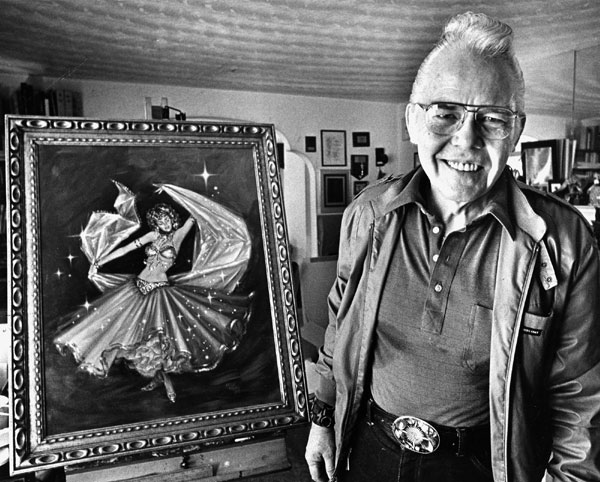

Rainy Days and Mondays: With a cup of coffee in front of me I might have been any commuter, but Laura and Kelly Freas hesitated, decided they knew a Hugo when they saw one, and joined me at my table beside the jetway snack stand. Once Kelly recovered from Laura’s discovery that the stand wasn’t licensed to sell any of the beer visible in a refrigerated display case until 8:00 a.m., and in fact was doing a land office business in muffins, he and I traded pleasantries about the Hugos.

Kelly remembered being offended by the shoddy 1970 Hugo base given at Heidelberg (“looked like scraps from someone’s barn door”), inexplicably bad woodwork from the country famed for Black Forest cuckoo clocks. When Freas got home he chucked the committee’s base and made his own. Bruce Pelz later told me – the 1970 Hugo bases truly were cobbled together from an old barn door by Mario Bosnyak when the real bases failed to arrive.

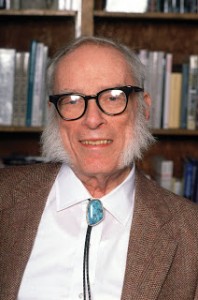

Isaac Asimov’s Speech at Noreascon Three: Over a thousand fans attended the featured event on Monday’s program, a speech by Isaac Asimov. Edward F. Roe sent me an account of what I missed. Here are some choice paragraphs from his report.

By Edward F. Roe: Asimov was asked to write a sequel to his Foundation Trilogy 30 years after its first publication. In the words of one of his critics, “nothing happens” in an Asimov story. “Nothing happens” means that no one gets killed, raped, or blows up the galaxy. When Isaac re-read the Foundation Series he commented, “You know, that guy was right. Nothing happens.” Asimov’s prose employs dialog heavily, and what the people say is interesting. Asimov went to the publisher and said he couldn’t write a sequel. The publisher took the time and explained it very nicely. He said get out of here, go home and write!

Asimov states that only people over 65 years old understand the Great Depression. To him it was the greatest disaster in human history not involving war or plague. It left him with a deep sense of insecurity. His family owned a candy store and he worked 16 hours a day, 7 days a week, except for school. It was impressed on Asimov that this was a normal work week, a habit he maintains to this day. He feels insecure when he is not working. He said, “Mentally I’m still imprisoned in that candy store.” Even though he has written many hundreds of books he still feels he has many books yet to write. He said that his dying thought will be, “Only six hundred?”

And with that Noreascon Three went into the history books as one of the best Worldcons ever. For most of the 6,837 members it was all over…except for the many volunteers who stayed to take apart the art show hangings, cart away the exhibits, roll up Warp Drive and Alice Way, and do the thousand-and-one other jobs involved in winding down a Worldcon. Even they were soon on their way out the door like everyone else, richer in memories and anticipating the new friendships they’d make next year in Holland.