By Brian Z. SF author and historian Andrew Liptak’s informative review essay, “Narratives of Modernization: China’s History of Science Fiction” is up at Barnes & Noble. Liptak places Chinese SF in its historical context and showcases some important works available in English, including Lao She’s 1930s interplanetary social satire, Cat Country, Cixin Liu’s short fiction collection, The Wandering Earth, and Chan Koonchun’s banned political allegory, The Fat Years.

On Saturday, August 22nd, 2015, author Ken Liu stepped up to the podium at Sasquan, the 73rd World Science Fiction Convention, to accept the Hugo Award for Best Novel on behalf of Liu Cixin, author of The Three-Body Problem. It was a historic moment: Liu Cixin’s novel was the first translated novel to ever win the award, one of the highest honors in SF/F fandom.

Precipitating this moment is a long history of science fiction in China. The genre enjoys its own vibrant tradition of speculative works, developed over the past century. Liu Cixin’s award comes at an interesting time for China: the Asian nation has become a major player in the world economy, and as it grows, its authors and culture are reaching new, global audiences, introducing the western genre culture to new worlds of ideas and stories.

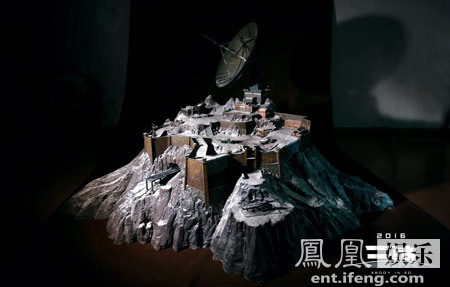

In related news, Cixin Liu fans might be interested in seeing two-meter high, three-meter wide model of Red Coast Base from the upcoming movie “Three Body” (July 2016), first unveiled at the Chinese Nebula Awards on October 18. Photos, not terribly well lit, have been posted on various websites (some accompany an article translated to English, “’Red Bank base’ debut tour family Nebula award Pictures called ‘three body’ will exceed expectations”, at Sunning View), and the Red Coast Base design sketch turned up on Facebook.

Just ahead of Chinese Nebula Weekend there had come news about the construction of China’s 500 meter Aperture Spherical Telescope, or FAST, prompting twitter users to ask: Red Coast Base?

“China enters the search for alien life with the construction of the world’s biggest radio telescope” at the Independent.

Chinese scientists are constructing the world’s biggest radio telescope, which will be more effective than any other at picking up weak messages from outer space that could be linked to intelligent life.

Assembly of the Five-hundred-metre Aperture Spherical Telescope, or FAST, began in July and is expected to be completed in 2016.

A rare glimpse at the massive telescope China built to talk to aliens. WATCH– http://t.co/vOw1ftiruL pic.twitter.com/WpDWImTmuo

— Slate (@Slate) October 19, 2015

@Slate Red Coast Base?

— Humpty D. (@Humperdinck_D) October 19, 2015

A CCTV news report from a while back included some interesting footage of the filming of “Three Body,” the actors and the special effects team, and some comments from Cixin Liu. Chinese only, but fun to look at.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Cool!

Andrew Liptak’s essay is bugging me. Modern Chinese history isn’t my specialty, but a lot of the essay seems to be misleading.

For instance, Lu Xun wasn’t part of the reaction to the 1900 Boxer Rebellion as the article suggests. He wrote and published his first story (“Diary of a Madman”) in 1918 and was part of the New Culture Movement, which emerged after the fall of the Qing.

However, he did early work as a translator. It was he who translated Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon–something Liptak at first doesn’t seem to understand–

–but later does. I don’t know what to make of that but it reads very confusingly and makes me think he doesn’t really know much about the topic.

And while it’s been awhile since I’ve read Lu Xun (and I read all of his fiction), I don’t remember him writing a sci-fi story. I wish Liptak had mentioned at least one story he wrote that was influenced by sci-fi. I wouldn’t be surprised if he wrote one, but it does not form a prominent part of his oeuvre. Not doing so seems like co-opting Lu Xun (often thought to be the greatest modern Chinese writer) to give sci-fi a more prominent place in Chinese literature.

In fact, he seems rather misleading throughout, playing up famous people’s connections to sci-fi. Lao She’s Cat Country is sci-fi, but calling him a sci-fi author is misleading. He is perhaps even better known as a realist, the novel Rickshaw Boy and the play Teahouse are perhaps his most famous work. Similarly, Hu Feng as far as I know is best known as a critic and poet, not a sci-fi author.

He also ignores Kang Youwei, Liang Qichao’s teacher (of sorts), who wrote Datong Shu which is a utopian work, albeit I’ve only read about it and it seems more to predict the future than be a fictional account of the future. It wasn’t published until 1935 or so but was circulating in manuscript form beforehand. I’m sure Liang Qichao knew of it.

He also uncritically quotes Xia Jia on the “Chinese dream.” The Chinese dream is simply Xi Jinping’s latest slogan. Every Chinese president needs one. It’s not a very good tool for analyzing history.

Also, to be honest, pretty much all the historical background he gives is extremely misleading if not flat-out wrong. I don’t think this is the fault of the one book of Chinese history he read, but the fact he seems to have read only one book, and a very short survey history at that. For instance,

This suggests that China had been unified before. That was not really the case. After the fall of the Qing (which the Guomindang played an important role, which is one reason why Sun Yat-sen is seen as the founder of modern China), various warlords took control of various parts. The Guomindang was located in the south, and helped unite China (still imperfectly) with its Northern Expedition in 1928. The Communist Party’s story at the time is very different; it was much smaller and uneasily allied with the Guomindang.

He seems to be on solid ground with modern Chinese sci-fi, but mainly because he is quoting others and seems to have read some of their work. Still, the overall impression I get is he really has no idea what he’s talking about.

@Shao Ping

Thank you for that. 🙂

@Shao Ping

Lu Xun was a science fiction translator a decade before the New Culture Movement, and Liptak claimed neither that he was a science fiction writer nor that Lao She was primarily one. (Though one could say that Cat Country was Lao She’s most politically problematic work).

Xia Jia’s statement seems accurate enough. Early 20th century writers articulated ideas about a modern “Chinese dream” prior to the political slogan.

Brushing past wrinkles in the convoluted history of Chinese communism might be clumsy, but to lay them out in their intricate glory would be rather too much for a Barnes & Noble blog post about science fiction.

You are quite right about Datong Shu, which was partly in response to Edward Bellamy. In fairness to Liptak, nearly everyone always misses that.

Liptak was wrong that:

But he wasn’t that far off. What Lu Xun read in New Fiction was a Chinese translation of (a Japanese translation of) Verne’s Vingt mille lieues sous les mers.

And Liptak is not the first to be fuzzy about what Lu Xun translated next: it was Inoue Tsutomu’s 1883 Japanese translation of Verne’s sequel, Autour de la lune, which included a very long summary of the first book.

Thanks for pushing back, but I still disagree.

Lu Xun was a translator. In his life he translated over 200 works. I don’t know how many of them were sci-fi, but it would have to be a lot more than two before I said he was a sci-fi translator. I’m also pretty sure translating was largely to supplement his income (he was first a student, then a teacher, and finally an important author in his own right), so even saying Lu Xun was a translator is misleading.

Liptak does say he was a sci-fi writer:

Liang Qichao’s book is not a translation, it is sci-fi (of a sort) he wrote. Lu Xun (and why call him Xun? I suspect Andy doesn’t understand Chinese names), as far as I know, did not.

He also suggests Lao She was primarily a sci-fi writer by lies of omission and by putting his death in the context of the Cultural Revolution bringing sci-fi writing to a halt. Technically true (a lot of literature grounded to a halt during the Cultural Revolution!), but misleading as all heck.

However,

sounds like it was because of Cat Country Lao She was targeted. That, I daresay, is wrong. I’m sure he was publicly criticized for things he wrote in Cat Country, but I’m also sure he was criticized for much else besides. The Red Guards would criticize people for all sorts of things! But Cat Country criticized China during the Japanese invasion so the immediate target was China under warlord and Guomindang rule. It didn’t target Communist China.

I’m unpersuaded Xia Jia’s statement isn’t repeating Chinese propaganda. Pretty sure you’re wrong about it being common before the slogan and even if it were, I would need additional convincing that Xia Jia wasn’t equivocating. Also pretty confident Lu Xun (and others) would hate the idea if he had heard of it. As he makes clear in his famous preface to Call to Arms, the point is not to dream but to awake.

Perhaps someone like Hu Shih who was educated in the US and wanted China to be a “democratic, independent, prosperous modern nation state” would, yet I don’t remember reading anything by him or about him that references it. So I hope he didn’t: it’s an ugly, vapid phrase

If you’re going to give background history, it should be accurate. All of Liptak’s history is misleading. He doesn’t simplify, he seems simply not to know what happened. Which is understandable since apparently he just read a very short introduction to Chinese history. I could equally have criticized other parts of his history, e.g.

The Opium Wars–awful as they were–weren’t particularly damaging to China, at least not in comparison to the Taiping Rebellion (and note: it was one, big rebellion though other, smaller ones also happened). The Taipings took over half of China and tens of millions of people died. This happened over a fifteen year period. The Second Opium War took place during this time, when the Qing were understandably occupied with the Taipings. Putting the Opium Wars first and not specifically mentioning the Taiping Rebellion is misleading. Also, the focus on Western influences also suggests that the book he relies on is a bit old (the author studied under Fairbank in the 50s, which shows), stressing China’s reaction to the West over forces inside China.

Still, that might do nothing other than instill misleading Chinese history in the reader or hint that Liptak simply doesn’t know much about Chinese history. It may not be important to the main article. (though why include it then?) Not tying Lu Xun to the New Culture Movement, however, is inexcusable. That is why Lu Xun is well-known. If not for that, he would have remained one translator out of many. And even then, I believe he was more in the tradition of Yan Fu, who translated important works in the 1890s, well before the Boxer Rebellion.*

As for Liptak being correct about Verne,

From Liptak’s account it seems Lu Xun read it in Chinese, liked it, then read it in Japanese and, not realizing he had already read it, decided to translate it. According to you, he read Vingt mille lieues sous les mers. That seems right from what I can find, but it means Liptak was quite wrong. Lu Xun didn’t realize that Jules Verne wrote both books, not that both books were the same. This is a fairly easy error to avoid and again points to Liptak not knowing what he is writing about.

And he was quite fuzzy about what he translated next: if not for your comment I would have had no idea it was the sequel to De la terre à la lune he translated, albeit one that apparently included a long summary of De la terre à la lune. When I Google “Travelling on the Moon” and “Verne” the only results I get are to Liptak’s article. Though to be honest, given most of the sources I can find says he translated De la terre à la lune and Voyage au centre de la Terre, I’m still rather confused about what he actually translated.

Any case, confusions aside, I still think he uses this to misleadingly make sci-fi more influential than it was.

So I stand by my original criticisms. Liptak’s article is extremely misleading due not to any maliciousness, but simply because he wrote about something he doesn’t really understand. His confusion is also plain in his writing, which at times is quite hard to follow. I don’t doubt Chinese sci-fi has an interesting history, but Liptak’s article is extremely misleading and doesn’t really touch upon it, focusing, instead, on already famous authors like Lu Xun and Lao She.

I imagine articles like this happen whenever something new appears. They are necessary and more accurate ones will follow. Doesn’t make them any less wrong or annoying though.

*”The Boxer Rebellion prompted a foreign invasion of Beijing, and ensured western access into China. The rebellion prompted a new progressive reformation in the country, which injected a wealth of western values into the country” also really annoys me (“progressive reformation” is just bad writing!), but enough is enough. I’ve gone on far too long.

I want to take that back a bit. It suggests sci-fi wasn’t influential. I’m sure it was! I’m also sure it (or maybe just Verne) also influenced Lu Xun. But Liptak’s article does a poor job showing how sci-fi was influential and where that influence was.

Lu Xun was not a sci-fi writer (though I imagine many readers will take that from this article). Yet an enormous amount of this essay is about him because he translated some Jules Verne as a young man–and Liptak can’t even clearly and accurately report what Verne he translated! Actual Chinese sci-fi stories like those by Huangjiang Diaosou and Lu Shi’e are given the most cursory of mentions, despite sounding interesting and part of a Chinese sci-fi tradition.

Ever more interesting.

I have found that the more I know about its subject, the less accurate the article seems to be. Rather disturbing. It causes me to take a lot of news articles skeptically.

I appreciate your frustration and your desire to see writers get the details right.

Even specialists in Chinese literature get fuzzy on some of these details, so what Liptak read in academic studies could have been incorrect or confusing. But sure, he got some things wrong.

If Lu Xun was a famous SF writer, the article would have mentioned some important genre thing he wrote, and it didn’t. Sure, that could have been spelled out.

The reason those wars and rebellions are important to this article is that in their aftermath there was increased exposure to Western ideas and literature – that could have been expressed better.

However. I think I have two other disagreements with you.

First, you objected to quoting without criticism a statement by a contemporary Chinese author because it is saddled with the vocabulary of contemporary Chinese nationalism. Yet the aim of the tor.com article was for Xia Jia to communicate her perspectives about the genre. She made a useful point – that early 20th century Chinese writers were searching for new, modern ideas and paradigms. Yes, she drew on loaded terms like Chinese Dream, 5,000 years of history, prosperous nation, etc., and those underscore the political context in which she is working. But we all have political contexts in which we write. Isaac Asimov did. Larry Correia and Jim C. Hines do. You and I do. It is great that Anglo-American fans can hear Xia Jia’s views, and I’m glad the present article linked to an interesting point she made without totally dissecting it.

Second, you are underestimating the importance of those early translations to Chinese SF. Can you imagine someone going on US television to promote their latest summer blockbuster being asked, which authors do you find most influential, and they answer, “Arthur C. Clarke and Jules Verne”? Because that’s China. With authors like Liu Cixin, understanding of how early SF created their building blocks, and the achievement of Lu Xun and others in building new vocabularies with which to tell their stories, can’t really be overemphasized.

Thanks for the conversation.

It can’t because he wasn’t, but the article nonetheless tries to claim he was–“In addition to Xun, other authors produced science fiction stories during this time.”

Rer: the Chinese Dream. We all have political contexts. However, from my experience most Chinese people know that slogans like the Chinese Dream are nonsense. No one takes them seriously even if when speaking in public artists and officials do. I doubt Xia Jia herself believes what she said. There’s certainly no reason for Liptak to. It’s propaganda.

Lu Xun translated two novels. There is no evidence in the article that those translations were influential (and some that it wasn’t, e.g. Liang Qichao–who at the time was extremely famous and influential–had already translated some Verne). There also isn’t much info on what other books were translated, how they were received, etc. Translations are important, but this article does a poor job of showing how they were important in China (and does quite a bit of bungling along the way).

I simply don’t think the author knows enough Chinese history or sci-fi to make interesting or accurate claims.

Heck, there isn’t even mention of how Chinese sci-fi (both original works and translations) roughly before the May 4th Movement would have been written in classical Chinese and afterwards in vernacular. Which would seem like a pretty big deal.

In my view, you are predisposed to give that sentence an ungenerous reading. I had simply understood it as a reference to the Verne translations. Perhaps we can agree to disagree.

If, as you are arguing here, not even Xia Jia thought that dropping the slogan “Chinese Dream” was anything more than a rhetorical gesture, and Chinese readers wouldn’t take it seriously, why not set it aside and instead comment on her substantive discussion of early SF? While it was hardly a rigorous scholarly treatment, I found it thought provoking and it seems very useful for fans not familiar with “New China” and other such works. You can disagree – but since all Liptak did was link to her discussion, you are being a little hard on him.

I guess the “novel claim” here is the importance of those early Verne translations to the development of Chinese SF. There have been studies of that, and it would be interesting to see one now, especially from someone like Liptak who I gather is probably as interested in the history of fans, writers and editors who made up the genre “community” as in doing traditional literary criticism. But more immediately, the article did give a clear sense of why those translations were important:

Its interesting to remember how writing (and translating) science fiction seems to have always had some kind of political purpose.

Interesting. Another one of those machine translated articles:

http://en.sunningview.com/article/41654

Liu Cixin revealed that his first contact with the French science fiction writer Jules Verne” geocentric Travels. ” “It was a hot summer evening, I think this book was found in the house his father, he took a book and gave me, and told me that called science fiction. I asked my father, this inside are out of fantasy? father said, is fantasy, but there are scientific analysis. This simple answer, established science fiction my whole philosophy, and continued to the present. ”

in Liu Cixin opinion, this traditional, core sci-fi concept is not widely accepted by the domestic literature. “We are more concerned about domestic science fiction theory, creation become very advanced, often trying to frame a ladder across a lot of things, and then reach a particular height. In fact, the science fiction terms, something difficult to cross, I also of those in other science fiction writers have crossed the road, and we must get down through such a phase. “

CONSOLIDATED LIST OF SCIENCE FICTION MOVIES:

These are the list of movies that will compete in the bracket. All of them had three or more nominations (including mine).

2001 (1968)

20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (1954)

A Scanner Darkly (2006)

Akira (1988)

Alien (1979)

Aliens (1986)

Alphaville (1965)

Avatar (2009)

Back To The Future (1985)

Barbarella (1968)

Bill & Teds Excellent Adventure (1989)

Bladerunner (1982)

Brazil (1985)

Bride of Frankenstein (1935)

Children of Men (2006)

Clockwork Orange (1971)

Close Encounter of the First Kind (1977)

Cocoon (1985)

Cube (1997)

Dark City (1998)

Delicatessen (1991)

District 9 (2009)

Dr. Strangelove (1964)

Dune (1984)

Escape From New York (1981)

ET (1982)

Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind (2004)

Fantastic Planet (1973)

Fantastic Voyage (1966)

Flash Gordon (1980)

Forbidden Planet (1956)

Frankenstein (1931)

Galaxy Quest (1999)

Gattaca (1997)

Ghost In The Shell (1997)

Ghostbusters (2016)

Godzilla (1954)

Guardians of The Galaxy (2014)

Independence Day (1996)

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956)

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978)

Iron Man (2008)

Journey to the Center of the Earth (1959)

Jurassic Park (1993)

King Kong (1933)

Logan’s Run (1976)

Mad Max: Road Warrior (1981)

Mars Attacks! (1996)

Matrix (1999)

Men in Black (1997)

Metropolis (1927)

Minority Report (2002)

Moon (2009)

Nausicaa of the Valley of the Wind (1984)

Paprika (2006)

Pitch Black (2000)

Planet of the Apes (1968)

Quartermass and the Pit (1967)

Repo Man (1984)

Return of the Jedi (1983)

Robocop (1987)

Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975)

Serenity (2005)

Slaughterhouse V (1972)

Sleeper (1974)

Solaris (1972)

Solaris (2002)

Soylent Green (1973)

Stalker (1979)

Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982)

Star Trek: First Contact (1996)

Star Wars (1977)

Starman (1984)

Start Trek IV: The Voyage Home (1986)

Strange Days (1995)

Summer Wars (2009)

Terminator 2 – Judgement Day (1991)

The Abyss (1983)

The City of Lost Children (1995)

The Day The Earth Stood Still (1951)

The Empire Strikes Back (1980)

The Fifth Element (1997)

The Fly (1958)

The Fly (1986)

The Hidden (1987)

The Hunger Games: Catching Fire (2013)

The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957)

The Iron Giant (1999)

The Man In The White Suit (1951)

The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976)

The Prestige (2006)

The Running Man (1987)

The Terminator (1984)

The Thing (1982)

The Truman Show (1998)

The War of The Worlds (1953)

Them! (1954)

They Live (1988)

Things to Come (1936)

THX-1138 (1971)

Time After Time (1979)

Time Bandits (1981)

Total Recall (1990)

Tremors (1990)

Tron (1982)

Twelve Monkeys (1995)

V for Vendetta (2005)

WALL-E (2008)

Wargames (1983)

Westworld (1973)

Young Frankenstein (1974)

Movies with too few nominations:

These movies had two or fewer nominations. If someone see that they missed a movie among these that they wanted to nominate, they have a short time to do so. Or just talk about a more unknown or misunderstood movie they think more people should have seen.

1984

2010

28 Days After

A Trip To The Moon

Airplane II: The Sequel

An America Werewolf in London

Appleseed: Ex Machina

Armageddon

Attack of the Block

Banlieue 12/District 13

Battle Royale

Beneath the Planet of the Apes

Capricorn One

Captain America: The First Avenger

Captain America: Winter Soldier

Cloud Atlas

Cloverfield

Coherence

Cold Comfort Farm

Colossus: The Forbin Project

Contact

Cowboy Bebop

Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon

Cube

Dark Crystal

Dark Star

Day of the Triffids

Deathrace 2000

Donnie Darko

Dune – Documentary

Eden Log (2007)

Edge of Tomorrow

Edward Scissorhands

Enemy Mine

Equilibrium

Escaflowne

Evangerion shin gekijôban: Ha

Event Horizon

eXistenZ (1999)

Fahrenheit 451

Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within

Flatland The Film (2007)

Flesh Gordon

Frankenstein: the true story

Frau im Mold

Gravity

Hancock

Hell Comes to Frogtown

He-Man and She-Ra: The Secret of The Sword

Her

I am Legend

Idiocracy

Impostor

Inception

Innerspace

Interstella 5555

Jin-Rô – The Wolf Brigade

Just Imagine

Killer Klowns From Outer Space

Life of Brian

Liquid Sky

Looper

Macross: Do You Remember Love

Mad Max: Beyond Thunderdome

Max Max

Memento

Millenium Acress

Monster vs Aliens

Moonraker

Mr. Nobody (2009)

MST3K the Movie

Next

Nineteen-Eighty-Four

On The Beach

Pacific Rim

Patlabor 2

Pi

Plan 9 from Outer Space

Predator

Predestination

Primer

Quest for Fire

Rise of the Planet of the Apes

Robinson Crusoe on Mars (1964)

Robotjox

Rollerball

Sexmission (Seksmisja)

Shaun of the Dead

Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow (2004)

Space Jam

Spider-Man 2

Spy Hard

Star Trek

Star Trek III: The Search for Spock

Stargate

Stepford Wives

Sunshine

Super 8

Superman

Testament (TV Movie)

Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989)

The 10th Victim

The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension (1984)

The Andromeda Strain

The Blob

The Book of Eli

The Boys from Brazil

The Brother From Another Planet

The Day After (TV Movie)

The Girl Who Leapt Through Time

The Haunted Place

The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy (2005)

The Hunger Games

The Illustrated Man

The Invisible Man

The Island Earth

The Last Man on Earth

The Man with Two Brains

The Mysterious Island

The Omega Man

The Quiet Earth

The Road

The Secret of NIMH

The Thing From Another World

The Time Machine

The Time Travelers Wife

The Zero Theorem

Timecrimes

Tomorrow I’ll Wake Up and Scald Myself with Tea

Treasure Planet

Under The Skin

Underworld

Up!

Upstream Color

Van Helsing

Waterworld

When Worlds Collide

Videodrome

Wings of Honneamise

(wrong thread for this one too)

I thought that Liptak essay was o.k., if, as people pointed out, not that up on Chinese history.

12 Hours later is a great source on Chinese Science Fiction and fantasy.

http://www.twelvehourslater.org/wp/2007/08/twelve-hours-later-about-this-blog/

Wow! Can we plead with them to update it more often? There’s some great stuff there.

From 2008: