By Carl Slaughter:

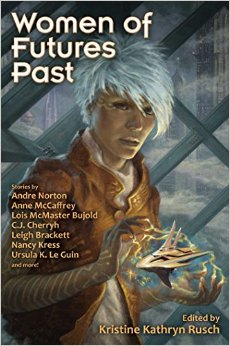

WOMEN OF FUTURE PAST

Editor: Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Released: September 6

Baen

Meet the Women of Futures Past: from Grand Master Andre Norton and the beloved Anne McCaffrey to some of the most popular SF writers today, such as Lois McMaster Bujold and CJ Cherryh. The most influential writers of multiple generations are found in these pages, delivering lost classics and foundational touchstones that shaped the field.

You’ll find Northwest Smith, C.L. Moore’s famous smuggler who predates (and maybe inspired) Han Solo by four decades. Read Leigh Brackett’s fiction and see why George Lucas chose her to write The Empire Strikes Back. Adventure tales, post-apocalyptic visions, space opera, aliens-among-us, time travel—these women have delivered all this and more, some of the best science fiction ever written!

Includes stories by Leigh Brackett, Lois McMaster Bujold, Pat Cadigan, CJ Cherryh, Zenna Henderson, Nancy Kress, Ursula K. Le Guin, Anne McCaffrey, C.L. Moore, Andre Norton, James Tiptree, Jr., and Connie Willis.

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Invisible Women by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

- The Indelible Kind by Zenna Henderson

- The Smallest Dragonboy by Anne McCaffrey

- Out of All Them Bright Stars by Nancy Kress

- Angel by Pat Cadigan

- Cassandra by C.J. Cherryh

- Shambleau by C.L. Moore

- The Last Days of Shandakor by Leigh Brackett

- All Cats Are Gray by Andre Norton

- Aftermaths by Lois McMaster Bujold

- The Last Flight of Doctor Ain by James Tiptree, Jr.

- Sur by Ursula K. Le Guin

- Fire Watch by Connie Willis

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

From Baen. Fuck. Oh, well, someone else can review it.

I read that – bought it because I thought there was an Andre Norton story in it that I hadn’t read as well as a few others, though it turned out later that I HAD read that Norton story and forgotten it. I didn’t mind seeing it again, though, as well as reading the stories that were new to me (which turned out to only be the Cadigan, the Kress and the Bujold). The stories themselves were uniformly excellent; though I was familiar with most of them, having read them in the Eighties and Nineties.

The preface, though, seemed – tendentious. Kristine Kathryn Rusch states the problem that women in the history of SF seem to be forgotten too quickly, even citing the fact that Locus once completely omitted her own tenure as the editor of F & SF when naming past editors, also that younger writers, including women, seem unaware of most of them. She states that the purpose of her anthology was to introduce the stories to younger readers who may not be aware that the stories and their writers existed. I was a little nonplussed at first; I’d read most of those stories in anthologies printed decades after they were first published, and didn’t think of them as ‘forgotten’ classics, but then I reminded myself I’m becoming a decrepit Old, and it’s surely a good thing to have a primer of these writers for the young who were not yet reading in the 80’s and 90’s.

I also didn’t have any objection to another of Rusch’s stated goals, to choose some of the stories in which men are the protagonists, and deal with “women’s issues” because ‘feminist anthologies’ tended toward choosing stories which deal solely with such issues and have female protagonists. Given that another of Rusch’s goals was to choose writers who were ‘successful’ in having a larger following of fans but have been left out of the “so-called canon” (who called it a canon? Rusch doesn’t say) of accepted classic female writers, even though those omitted writers had a much larger following than the “canon” writers, I can’t blame her for choosing stories to have as broad an appeal as possible to increase potential sales.

What I do have a problem with, is her broad statement that “The idea that women are discriminated against in science fiction is ludicrous to me.”

Yes, it is certainly a problem that younger female writers feel that SF is hostile to women, and feel that the few female predecessors they know of are ‘the exception’, and that they are ignorant of many others. But I think to flatly state that their impression of discrimination is utterly false isn’t necessarily convincing…and the fact that she uses a series of straw men to ‘prove’ her argument doesn’t strengthen it.

“But the narrative in which there has been no female participation in SF, no women writing SF, in which women had to hide under pen names and initials because of being discriminated against…that narrative has triumphed over the truth.

That narrative is insulting. It’s demeaning. And it’s wrong.”

Sure, it’s insulting and demeaning and wrong. But I’m pretty sure no one – not even the young ignorant writers she rails against who believe in the laughable bogeyman of discrimination – believe that there has been NO female participation in SF. AFAIK, they only believe that women have been published less, and marginalized and forgotten more than their talent actually warrants.

As for pen names and initials…in Rusch’s introduction to C. L. Moore’s “Shambleau” (a story I love, BTW) Rusch tells us:

“And now, we ease into the mythbusting part of our anthology…Articles on discrimination against women in SF consistently cite Catherine Lucille Moore’s 1933 decision to use her initials as a byline as proof that she was afraid she would be discriminated against for her gender.” She then cites some biography to say (not in a quote from Moore) that “she used her initials because writing for the pulp magazines was a disreputable thing to do – for men and women – in the 1930’s, and she was afraid of losing her job in the depths of the Depression.”

This is pretty thin stuff. The fact that she wanted to protect her job does not logically exclude the possibility that she might ALSO have wanted her gender to be less obvious to publishers and readers. It becomes even thinner when you realize Rusch is well aware that Moore used many pseudonyms in her career – she even mentions it herself (“She was so prolific under many names, with Kuttner and on her own…”). But, oddly, Rusch omits to mention that most of those pen names – maybe ALL of them – were either asexual or masculine. Since I doubt such an eminent SF personage as Rusch was ignorant of that, I can only conclude she deliberately omitted it to strengthen her argument of ‘no discrimination in SF’.

Why? I’d guess because of something she said about another goal of the anthology: “I did not want the stories in this volume to have a political slant. This introduction and the introduction to the stories have a slant, because I’m trying to introduce the important women writers of science fiction to a generation who does not know they exist.”

To Rusch’s credit, I think her selected stories do not have an overt political slant. But the introductions – why do they require Rusch to pooh-pooh the idea that women in SF were ever discriminated against before she allows the reader to dig in to their goodness? Who is her intended audience of people who do not know women in SF ever existed, but need a spoonful of sugary reassurance that them feminists were full of it before downing what they anticipate to be the bitter medicine of a story by a woman? Do I hear the dulcet tones of puppywhistles in the air?

The rest of her proof of nondiscrimination is equally thin. She cites someone who made a careful count of all stories in SF magazines from 1926 to 1965 (heroic indeed) and found “at least” 233 women writers who published a total of 1055 stories in that time. Gosh wow! That’s a lot. And how many total stories and male writers of such, so that we can do the simple math ourselves and see whether the percentage of women is around the 50% we would expect if we accept Rusch’s premises that women have no specific handicap in writing sf AND that there is no discrimination against them in the field? Oddly enough, that number’s – not there.

The most upsetting part of the introduction, to me, was Rusch’s treatment of Joanna Russ. To me, if you’re going to talk about the erasure of women from the SF field, you kind of HAVE to talk about Russ’ contribution regarding how to suppress women’s writing – whether you’re going to agree or vehemently disagree with her views. Rusch does neither. She only brings up Russ to dismiss her briefly: “In the 1970s, Joanna Russ doubly dismissed hearth-and-home stories in her analysis of the kinds of SF women tend to write. She called hearth-and-home stories either “galactic suburbia” or “ladies science fiction” which she defined as stories “in which the sweet, gentle, intuitive heroine solves an interstellar crisis by mending her slip or doing something equally domestic after her big heroic husband has failed.”

Now, Russ is pretty clearly castigating writers like Mildred Clingerman, whose ladies-in-the-domestic-sphere stories do match Russ’ sarcastic description. Russ was no doubt wrong to dismiss such writers wholesale. But Rusch is wronger than Russ when she says this:

“Russ, as with many critics, often couldn’t see the forest for the trees. Clingerman’s fiction, for example, is extremely subversive and biting. Yes, her intuitive heroines solve problems in untraditional not-always-heroic ways and that is the point. Clingerman, [Shirley] Jackson, early Kit Reed, all focused on powerless people who managed the world much better than the powerful.”

Stop, Rusch! STOP RIGHT THERE!

Do you REALLY think that Joanna Russ was such an idiot that she described any of Shirley Jackson’s protagonists as “the sweet, gentle, intuitive heroine” who problem-solves the apocalypse with her sewing kit? Again, I can’t imagine that you do, and the picture of you straw-manning words of attack on Shirley Jackson into Russ’ mouth that she surely didn’t intend is distasteful to me.

Funnily enough, after defending Mildred Clingerman from Russ, Rusch – didn’t actually include any stories of Clingerman’s in her anthology. Though some of Clingerman’s stories are pretty good, I’d guess that despite all Rusch’s condemnation of Russ’ judgement, Rusch DID tacitly agree by omission that Clingerman’s works aren’t quite good enough to have withstood the test of time.

So, in conclusion – the set of stories themselves are an excellent introductory anthology to these writers. But Rusch’s editorializing is not a lot of value added to it.

By any change, did she cite Partners in Wonder: Women and the Birth of Science Fiction 1926-1965 — Eric Leif Davin ? Because some of the rhetorical stances sound familiar.

Actually, yes. Devin was the guy she cited who’d counted up all the stories in the SF magazines and the female authors he’d found between 1927 and 1965. I’d be interested to know how much of what Rusch said was based on his work (though if it strikes the same confessed political slant I wouldn’t read it with too much trust).

One aspect of Devin that really stood out was the bit where he tried to rehabilitate Campbell’s reputation.

I noticed last year Devin seems to be the go-to critic for the Puppies and their ilk.

I further remember that back when GvG was editor of SF&F, Rusch defended him from accusations that he was buying a smaller proportion of women writers. The problem was, checking the stats to verify that yes, GvG bought fewer works by women than his predecessor is trivial to do.

@Jayn: To be fair, the one Mildred Clingerman story that I recall, “Letters from Laura” (which I encountered in Boucher’s A Treasury of Great Science Fiction) is subversive and biting, and very funny. But that caveat aside, point thoroughly taken.

@James Davis Nicoll: I just read your review of Devin’s work. Very good (I especially liked being introduced to the concept of the “curate’s egg”.) And yes, that does sound a lot like the tone Rusch took.

@PhilRM: I actually do like what little of Clingerman’s work that I’ve read (which is not a lot; I mainly found her in older secondhand anthologies going yellow and crumbly). It was mostly light and fluffy comedy with traditionalist female characters, mainly of the housewifely or soon-to-be-housewifely persuasion, though it’s true in at least some of the stories there were undertones signalling that the lady in question is less happy with her role than just resigned to it. IIRC, her more serious stuff was from the same point of view but more overtly liberal politically. Whether that makes it better or not may be a question of taste. The description of “Letters from Laura” in Jennre looks fun; will try to find it on Amazon.

Compared to Lisa Yaszek and Justine Larbalastier, who did similar studies of women writers in early science fiction, Eric Leif Davin clearly has an axe to grind with feminist science fiction in general and Joanna Russ in particular.

Regarding the anthology, I had pretty high hopes for the project (and that cover is positively subdued for Baen), but those supposedly forgotten women writers are all pretty big names. Including someone like e.g. Mildred Clingerman would have been good. I’ve also read most of the stories before, so I’ll probably pass.

I have just spend twenty minutes on isfdb and I can say with some confidence I have never read a story by Clingerman.

Can’t find any e-books of hers on Amazon. The cheapest new paperback anthology with ONE story of hers in it is 26 bucks. There’s a Facebook page (apparently run by a relative) that says they’re planning to reprint her collected stories, A Cupful of Space, sometime soon (though this was last updated November 2015).

@Jayn

I read that intro a while ago, and I think you’ve put your finger on exactly what confused me about Rusch’s argument.

I think she needed to identify who was actually saying the things she was arguing against.

Other than that the anthology looks really interesting – I particularly want to read the Cherryh.

Most of the stories are available to read for free online (links here).

I just looked at the contents and I’m kind of disappointed. I have all but one of them in my library (I don’t think I have the Brackett) and I’ve read them all. None of the authors can be considered obscure in the least.

There’s not much point for me to buy the anthology.

Luckily, I, too, am an Old and thus have read all and own most of them; I shan’t have to sully myself.

Is it a Baen requirement that good old content be encumbered by bad new editorials? Seems to happen a lot with their reprints.

Kinda puzzled why McCaffrey, Bujold, and Willis are even in it, though — they all won Hugos, Anne sold about a bajillion books and Lois and Connie are still writing and selling a lot and getting Hugos. Would have preferred to see older and less well-known (today) authors.

lurkertype: Kinda puzzled why McCaffrey, Bujold, and Willis are even in it

Maybe to bolster the (in my belief incorrect) assertion that women in SF haven’t been marginalized?

I’m mystified by the TOC, too. I’d have preferred that neither they nor LeGuin were in it. Why not give bandwidth to little-known, underappreciated women authors?

But then I guess that would have contradicted the narrative of the introduction. 😐

@JJ: Aha! QED. Can’t contradict the narrative. (Avoid the narrative!)

Still, there are women who were publishing regularly back in the day (which would fit the narrative) who could use more of a boost today. If I was doing a similar anthology of men, I’d pick men who used to be “the thing” in the 40s-80s and then disappeared. Surely there could have been 4 other women who could have been in it, of the Henderson or Kress sort. Why NOT Clingerman?

How about Katharine Burdekin? (oops, contradicts narrative — she wrote as Murray Constantine… but then why is Tiptree allowed in?) Octavia Butler, FFS. Suzette Haden Elgin!!!

There’s an answer regarding Butler in the preface, at least…Rusch specifically wanted one of her stories but couldn’t come to an accord with the estate about it.

Interested in see what she says about Connie in the introduction. Definitely not an overlooked writer or story.

Gah. I’m a New who has heard of all these authors but not read any of the included works except the Tiptree, so this could have been perfect. But reading about Rusch’s editorial line has taken it down from a “will buy” to a “probably give it a miss”. I have other ways to broaden my reading on women of the genre without putting up with dismissive and disingenuous editorialising.

On the plus side, this comment thread has actually introduced me to some new names. So that’s a success!

You can have my copy if you like. The stories are really good. And if it gets some puppies reading the authors, I suppose it can transcend the rest and be a net benefit to some.

Tomorrow, I shall try to come up with a better TOC. Unless I forget.

James Davis Nicoll: Tomorrow, I shall try to come up with a better TOC. Unless I forget.

Oh, I would really like that. I would like to be better-read in the less-well-known women SF authors.

“The rest of her proof of nondiscrimination is equally thin. She cites someone who made a careful count of all stories in SF magazines from 1926 to 1965 (heroic indeed) and found “at least” 233 women writers who published a total of 1055 stories in that time……Devin (sic) was the guy she cited who’d counted up all the stories in the SF magazines and the female authors he’d found between 1927 and 1965. I’d be interested to know how much of what Rusch said was based on his work (though if it strikes the same confessed political slant I wouldn’t read it with too much trust)..”

– If it doesn’t follow the ideological line, then it can’t possibly be true. When the Right does this with global warming denial, liberals and the Far Left justifiably groan and shake their heads, and justifiably so. But, oh – we can’t possibly actually READ Davin’s (yes, Jayn, that’s Davin, not Devin, Eric Leif Davin, professor of history at the University of Pittsburgh, winner of the Eugene V. Debs Foundation’s Bryant Spann Memorial Prize in Literature for his historical writing) who time and time again has his actual research quoted whenever someone, in this case a woman (!!!) goes against militant victimology and identity group ideology. But when science or academic research goes against the ideological line of extremists of the Far Left or the Far Right, denial becomes imperative and politically, well, correct. Davin has been referred to and quoted again and again as a respected authority when these discussions come up. Over and over again, it is suggested that people go out and buy his book or get it from the library and actually read it. But we couldn’t do that now, could we? How can you not have heard of him, unless you never stick your head out of the echo chamber it must be stuck in? You might find some interesting info, such as the fact that, along with women’s SF/F being published more in the Teens, 20’s and 30’s than in the post-WWII era, in parallel, more women were getting scientific degrees in those earlier decades. Pick up some old copies of Amazing Stories from the 1920’s. You will see that Gernsback and Sloane published line drawing portraits (yes, actual female faces!!!) and brief biographical sketches of women authors along with male authors, at the beginning of each story, giving lie to the claim that unless a women wanted to come out from behind initials, she and her work were discriminated against or blacklisted, and of course ignored by readers. Davin’s book gives a more nuanced critical view of the history and dynamics of the publishing and progress of women in the early 20th century. (In the future, similar well researched studies of the treatment and success or difficulties of women in SF will perhaps study changes, decade by decade, in the SF literature, the world around it, the publishing industry, and writers’ changing society and support systems.) I could go on and on, but what would be the point? Anything that Rusch, Davin, or I would say would be dismissed because it doesn’t fit the Party Line. SF history, earlier SF writers, and the backlist used to be regarded with affection and respect by fandom and the SF community. Now, they are fashionably pissed on as hopelessly reactionary and worthless. They’re sneered or patronized in Locus. Unless, it appears that some can be resurrected to fit somebody’s political agenda……

KBK: If it doesn’t follow the ideological line, then it can’t possibly be true

Okay, KBK, so you tell me: during the 40-year period that Davin says “at least 233 women writers published a total of 1055 stories”, how many men published how many stories? 2,000 men publishing 8,000 stories? 5,000 men publishing 20,000 stories? How many?

Why isn’t Davin including that information in his claim that women SF authors have not been marginalized?

I have a pretty good idea why.

ETA: Note that Davin’s statistics mean that an average of 6 women a year published an average of 26 stories a year. Woo-hoo.

“Past” (the final word of the title) seems an odd fit for a book of works in which 42% of the authors are still alive and writing. Not so much with the “respect for the unknown backlist” either; these are almost all works you can find easily anyway. I’d rather have seen works by the other 230 writers. Heck, some of those stories might have slipped into public domain and then no problem with estates, either.

230 women over 40 years of who knows how issues of how many magazines is a pitiful amount, BTW — especially without the comparable stats for men. Did the learned Davin bother to count those up, or didn’t that fit into his narrative?

HOLY EFFING SHIT. The Kindle version of Davin’s book is $35.25. Used paperback versions start at $41.00. A new copy is $51.00.

Why wouldn’t people read the book?

WTFF. 😐

@KBK

Goodness, that’s a remarkably … enthused … denouncement of everyone who is simply questioning Rusch’s editorial line. I’m afraid that, like Rusch, you seem to be arguing with stances that people aren’t actually taking.

That’s a remarkably unawful cover for Baen. And no mention of an extended afterword by Sarah A. Hoyt.

Rule of thumb. If someone’s not got their own Wikipedia page then it’s reasonable to think that they’re not a household name. Not meaning that Wikipedia is the only source of knowledge, but when someone who everyone knows about doesn’t have a page then someone’s going to create it sharpish.

He has no entry. Therefore I’m not the least bit surprised some of us have never heard of him.

From the “well isn’t that interesting” dept, I had a re-read of James review of Davin, and who do I find leaving a long comment at the bottom? KBK of course.

The review is interesting for revealing, for example, that Davin didn’t pay much attention to the question of proportions, mostly just showing that there were some women getting published – a proposition that I don’t think anyone sensible has denied.

@KBK

Mea culpa on the Davin misspelling, mine is the sole blame. Which doesn’t change the fact that saying “233 women writers who published a total of 1055 stories in that time! Gasp, that’s a lot!” proves doodly-squat about whether or not women were discriminated against, unless you provide the total numbers of male writers and the stories they published in that time, so that you can check the proportion of women against them.

Now, maybe Davin DID provide those numbers in his work (I’m not spending 35 bucks on Kindle to find out right now) but KKR did not, and hers is the book that I’m critiquing. Regardless of the source, the incomplete figures KKR provides don’t prove anything on their own, certainly not the lack of discrimination she swears is a fact, and they seem misleading. Now KKR acknowledges there is a political slant in her preface and story introductions. She declares this is necessary (why? not explained) to introduce these writers to a younger generation. But if that slant requires her to call anyone who believes that women were ever discriminated against – whether in 1927 or today – ludicrously deluded, then she’s got to be rigorous about her proofs, and she’s not. She misleads in her figures, and she omits and misleads in the other points I touched on in my review (as well as dismissing and straw-manning one of her eminent predecessors on the subject).

I’d say it’s not a stretch to assume that it’s her political slant that causes her to omit points that would undermine her preferred conclusion and give misleading numbers that seem to support it. And as I said, if Davin uses the same slant that KKR used, I’d read his work with mistrust, just in case he is also misleading the way KKR seems to be.

Note well that I didn’t say I would refuse to read it, merely read with mistrust, as you might read, say, the New York Times. 🙂 And I might well do that if I do come across his works in a library. And no, the fact that I won’t spend money on them is not an indication of my closed-mindedness. I have never spent that kind of money on a book of pure academic analysis, regardless of its political leanings. I have the Women of Wonder series because it had STORIES in it – stories I never would have read any other way – though I read their literary analysis with enthusiasm. I bought and own KKR’s Women of Futures Past because it has STORIES in it. At bottom, it’s the stories I love. And (as I acknowledged in my original review) KKR’s choice of stories was impeccable. I wish she hadn’t chosen to surround them with slanted special pleading. If my review pointing that out puts some people off buying the book, I don’t think that’s too much of a loss, because (as others have pointed out) most of these authors are not that “forgotten,” still in print and easily available. I did and do highly recommend them all.

Disco Era debuts is easiest, because that’s when I started reading in an organized way and also I have a list. Snipping out the ones whose work I don’t care for, the ones I have not read, and the ones I think are very well known. I’ve added one suggested work, generally of novel length (because to my surprise, when I looked at the magazines and Best Ofs of the 1970s, women were very scarce). Many of the books are more recent than the 1970s.

Eleanor Arnason: A Woman of the Iron People

Joy Chant: Red Moon and Black Mountain

Suzy McKee Charnas: Walk to the End of the World was

Jo Clayton: Diadem from the Stars

Phyllis Eisenstein: Born to Exile

Dian Girard: “The Nothing Spot”

Monica Hughes: The Keeper of the Isis Light

Leigh Kennedy: Wind Angels

Lee Killough: The Doppleganger Gambit

Katherine Kurtz: Deryni Rising

Elizabeth A. Lynn: Watchtower

Vonda N. McIntyre: Fireflood and Other Stories

Patricia A. McKillip: The Riddlemaster of Hed

Janet Morris: Ha ha ha no. Well, some shared universe thingie like Heroes in Hell, if you insist

Pat Murphy: The City, Not Long After

Rachel Pollack: Temporary Agency

Marta Randall: Islands

Pamela Sargent: Venus of Dreams

Sydney J. Van Scyoc: Assignment Nor’Dyren

Nancy Springer: Larque on the Wing

Lisa Tuttle: Lost Futures

Joan Vinge: Eyes of Amber and Other Stories

Élisabeth Vonarburg: Reluctant Voyagers

Cherry Wilder: The Luck of Brin’s Five

It sounds like a great anthology overall, but by no means is it a list of unknown or forgotten writers.

I’d like Rusch to explain exactly how Anne McCaffrey or Ursula K Le Guin have been forgotten or ignored by the current generation of feminist writers. (Critiqued, yes, in for example the examinations of what exactly dragon mating entails for the mindbonded human) but to critique one must read. And the more common reaction to both I’ve encountered is more along the lines of “Inspired by”.

And Connie Willis and Lois McMaster Bujold? I don’t consider them ‘of the past’ at all. They’re contemporary.

Ooh, that’s a good list based on the ones I’ve read.

I’d theorize that *if* Monica Hughes is forgotten (And her books still show up around here) it’s because Canadian not female.

I was delighted when someone pointed me to Marta Randall’s The Sword of Winter. She made the comment it included one of the most realistic child characters she had encountered. It does, and also a great adventure.

I recall reading and liking Janet Morris. But I was a teen young enough my mom was worried about the sexual content, though not worried enough to stop me. Have not read her since. (The other similarly worrying stuff at the same age was Joan D. Vinge, whose work I have reread as an adult and whose biggest classics hold up well IMO, though some of her output is uneven.)

@James Davis Nicoll, Seconding Lenora Rose — I’ve read a little over half of the suggested titles (and other works by about half of the authors whose cited titles I have not read) and that’s a very strong list.

One wonders how Bujold and Willis like being called of the past?

Maybe novels were cheating. Let’s see what I can come up with from memory:

Sonya Dorman: When I Was Miss Dow

Dian Girard: … And Settle Down with a Good Book

Zenna Henderson: The Anything Box

Lee Killough: Aventine

Elizabeth Lynn: The Woman Who Loved the Moon

Ardath Mayhar: Who Courts a Reluctant Maiden

Katherine MacLean: The Snowball Effect

Wilmar H. Shiras: In Hiding

Margaret St. Clair: The Man Who Sold Rope to the Gnoles

Evelyn E. Smith: Collector’s Item

Lisa Tuttle: The Bone Flute

Joan D. Vinge: Media Man

Cherry Wilder: Mab Gallen Recalled

Cassie B: the 1970s were an awesome time to be exploring SF, though I think the current era and its vast troves of e-books is even better.

COMMENT FASTER, PEOPLE.

I used to run into this problem on tor.com, where I would make six comments in a row as ideas came to me. This did not go over well with other commenters and made me worry I was tor.com’s Vos Post. Although as I might someday mention to Charles Stross, Ann Leckie, Kameron Hurley or John Scazli, at least *I* don’t shamelessly namedrop.

What about Candas Jane Dorsey and Margaret St. Clair?

Tanith Lee? Her output was uneven, but when she was good she was very VERY good. I recommend Biting the Sun among her multiple novels.

I had a St Clair but I am ashamed to admit I don’t think I have knowingly read a Dorsey.

(I also have a gigantic Shirley Jackson-shaped hole in my reading, The Haunting aside)

@Jayn

Which doesn’t change the fact that saying “233 women writers who published a total of 1055 stories in that time! Gasp, that’s a lot!” proves doodly-squat about whether or not women were discriminated against, unless you provide the total numbers of male writers and the stories they published in that time, so that you can check the proportion of women against them.

But even if you had complete publication statistics, men and women, I don’t think you could authoritatively say anything about discrimination. You’d need numbers on how many stories were submitted by men and and by women before you could make that case, and I can’t imagine that that particular data set exists anywhere.

One could check to see if particular editors at major magazine ever said they wouldn’t buy from women or published editorials or letters complaining bitterly about women writers.

@Bill

If that particular data doesn’t exist for this subject (or any other subject) why can’t we talk about it with the facts we do have? To suggest otherwise would mean abandoning most studies of, say, history on the grounds that we don’t know everything.

@KBK

I don’t think anybody here is disrespecting Davin’s work – since doing a survey of how many women published SFF during the pulp era is certainly a valuable undertaking. However, several people here disagree with his conclusions or rather the ones Kristine Kathryn Rusch draws.

What is more, Partners in Wonder is very expensive, even by academic publishing standards, which makes it difficult to access, unless you live near a university library which happens to have it (mine doesn’t, though Göttingen probably does). I have an academic interest in SFF criticism and still haven’t purchased a copy because of the price tag. What is more, Justine Larbalastier’s The Battle of the Sexes in SF and Lisa Yaszek’s Galactic Suburbia, both of which are highly recommended BTW, cover similar ground at a cheaper price tag.

@James David Nicoll and Lenora Rose

“Keeper of the Isis Light” by Monica Hughes has the distinction of being the first SF novel I read. Somehow, it ended up among all the boarding school stories and “realistic” problem YA in the spinner rack at the local news agent.

@Bill

Good point. Will address when I’m home with the book.

A propos of nothing, an event of moment – I just found a used bookstore that was new to me in NYC! Center for Fiction, 17 E. 47 st. Must browse.

@Mark

If that particular data doesn’t exist for this subject (or any other subject) why can’t we talk about it with the facts we do have?

You can talk about discrimination against women SF writers all you want. I’m just saying that the data mentioned (how many stories published by women in this period) don’t support any conclusions that women were discriminated against. Total # of stories published is only part of the data you need.

To suggest otherwise would mean abandoning most studies of, say, history on the grounds that we don’t know everything.

No, I don’t think so. You can study history and draw conclusions when the data you have are sufficient to support (or detract from) those conclusions. You don’t need to know everything.

(And, just to be clear, I am not saying that women weren’t discriminated against.)

I’m interpreting “discrimination”, in this context, to mean that a woman who submitted a story had a lesser chance of getting it published than a man who submitted an equivalent story, based on her being a woman.

If you want to argue that the way society treated women in general in that time period prevented women from ever writing or submitting stories, and that environment was discrimination, and that a small number of published stories is evidence of that discrimination, then I can see the point, but I believe that this data set is still too small to fully support the argument.

As far as deducing Rusch’s motives and reasons, we’re in luck. Rusch kept a blog for the last year and a half while she was reading for this anthology, which was originally to be titled “Tough Mothers, Great Dames, and Warrior Princesses: Classic Stories by the Women of Science Fiction”.

http://www.womeninsciencefiction.com/

In certain instances she explains that if she selects a long novella like “Fire Watch” then it will devour much more of the total 100,000 words for the book. In fact she acknowledges in her most recent post that her favouring novellas has meant the exclusion of other shorter stories, such as Mildred Clingerman whom she likes a lot.

http://www.womeninsciencefiction.com/?tag=mildred-clingerman

One of the motives for editing she claims was “I’ve been told repeatedly by young female writers in the sf genre that women never did anything in sf until the year 2000 or so,” which she takes partly as an affront from young women. If that’s the case then, while Connie Willis and Le Guin are very much alive, the stories she’s selected by them are almost 35 years old. I’ve read them, you’ve read them, many File770 commenters have read them, but we’re not necessarily the audience.

And as for it being published by Baen:

“…a corrective volume of fiction by the women of the field—the influential women of the field… I knew exactly who I wanted to pitch this book to—the woman who heads a major science fiction publishing house, who published and continues to publish some of the most famous women sf writers in the field. I sat down with Toni Weisskopf of Baen and talked to her about the invisible women in the field and what we could do about it…. I knew my politics and the perceived politics of Baen were on opposite ends of the political spectrum. So the pairing of two long-time female professionals, me and Toni, from different backgrounds and with different perceived political perspectives, was something else this project needed. I want the field to understand that women work in all parts of the field, both physically and intellectually. We don’t have the same views of the world, but we’re here, we’re working, and we’re making a difference.”

Rusch’s original manifesto:

http://www.womeninsciencefiction.com/?p=31

Her final thoughts:

http://www.womeninsciencefiction.com/?p=620

@Bill

So, you’re happy to draw conclusions from limited data in other circumstances, but you’re claiming that the data is insufficient to draw any conclusions in this case?

I think the bar you’re setting is too high, especially if you’re happy to to see historians reach conclusions based on, say, data on medieval demographics.

I will, on at least two grounds.First, quoted from my review:

he quotes the most strident section of Shawna McCarthy’s 1983 discussion of women in SF (which appeared as an editor’s note in Isaac Asimov’s Space of Her Own and is not so far as I know linkable], he relegates her later admission that she was overstating the case to his endnotes.

That seems … thoughtfully misleading.

Secondly, his attempt to rehabilitate John W. Campbell, Jr’s reputation seems misguided at best.

While I appreciate his bean-counting, having done some myself, it seemed like he was highlighting the material that supported his case while ignoring or concealing in end notes material and context that might contradict his thesis.