(1) VISIT A BRADBURY HOME. The house Ray Bradbury lived in when he was 11 years old will be included in Tucson’s Armory Park home tour, which will be happening November 12.

From the outside, Dolores and Jerry Cannon’s house looks like an antique dollhouse with a white picket fence — not the kind of place one would think the author of such celebrated books as “Farenheit 451” or the “Martian Chronicles” once lived.

But it is — Ray Bradbury called the Armory Park home in 1931, when he was just 11. You can imagine where he might have gotten some of his early inspiration on the Nov. 12th Armory Park Home Tour which will include 15 homes.

The Bradbury family lived in Tucson, Arizona at two different times during his boyhood while his father pursued employment, each time returning to Waukegan.

(2) NO ENVELOPE, PLEASE. Adrian Tchaikovsky’s guest post for SFFWorld, “Mad Science and Modern Warfare”, describes the tech in his MilSF novel Ironclads.

Ironclads is set in the near future. There’s a lot in the geopolitics and social elements of the book that is a direct, albeit very negative extrapolation from the way things are now. The technology, though, goes to some odd places, and I was conscious of not just pushing the envelope but ripping through it a few times. I like my science fiction, after all, and some of what Ted Regan and his squad face up against has more fiction than science to it.

“Designed for deep insertion.”

Most of Ted’s own kit, and that of his squadmates Sturgeon and Franken, is not much different to a modern military payload, but then the chief lesson Ted’s learnt about the army is that they get yesterday’s gear compared to the corporate soldiers. Hence their vehicle, the abysmally named ‘Trojan’, is not so far off a modern armoured car – resilient and rugged but, as the Englishman, Lawes, says, “what soldiers get into just before they get ****ed”. Most of the rest of their kit is drawn direct from cutting edge current tech. Their robotic pack-mule is a six-legged version of the “Big Dog” robots currently being developed, and the translation software in Ted’s helmet isn’t much beyond what advanced phone apps these days are being designed to do.

(3) BREAKTHROUGH ARCHEOLOGY. “Unearthing a masterpiece” explains how a University of Cincinnati team’s discovery of a rare Minoan sealstone in the treasure-laden tomb of a Bronze Age Greek warrior promises to rewrite the history of ancient Greek art.

[Jack Davis, the University of Cincinnati’s Carl W. Blegen professor of Greek archaeology and department head] and Stocker say the Pylos Combat Agate’s craftsmanship and exquisite detail make it the finest discovered work of glyptic art produced in the Aegean Bronze Age.

“What is fascinating is that the representation of the human body is at a level of detail and musculature that one doesn’t find again until the classical period of Greek art 1,000 years later,” explained Davis. “It’s a spectacular find.”

Even more extraordinary, the husband-and-wife team point out, is that the meticulously carved combat scene was painstakingly etched on a piece of hard stone measuring just 3.6 centimeters, or just over 1.4 inches, in length. Indeed, many of the seal’s details, such as the intricate weaponry ornamentation and jewelry decoration, become clear only when viewed with a powerful camera lens and photomicroscopy.

“Some of the details on this are only a half-millimeter big,” said Davis. “They’re incomprehensibly small.”

…“It seems that the Minoans were producing art of the sort that no one ever imagined they were capable of producing,” explained Davis. “It shows that their ability and interest in representational art, particularly movement and human anatomy, is beyond what it was imagined to be. Combined with the stylized features, that itself is just extraordinary.”

The revelation, he and Stocker say, prompts a reconsideration of the evolution and development of Greek art.

(4) GRRM’S ROOTS. George R.R. Martin will make an appearance on a PBS series:

Day before last, I spent the afternoon with Dr. Henry Louis Gates Jr, taping a segment for his television series, FINDING YOUR ROOTS.

I thought I had a pretty good idea of my roots, but Dr. Gates and his crack team of DNA researchers had some revelations in store for me… and one huge shock.

PBS is currently airing Season 4 of Finding Your Roots, with episodes featuring guests Carmelo Anthony, Ava DuVernay, Téa Leoni, Ana Navarro, Bernie Sanders, Questlove, and Christopher Walken.

(5) PKD: STORY VS TUBE. Counterfeit Worlds, a blog devoted to exploring the cinematic universes of Philip K. Dick, has published a series of weekly essays comparing and contrasting each episode of Philip K. Dick’s Electric Dreams (which has been airing in the UK) with the original Philip K. Dick short story. The series will soon be available in the U.S. on Amazon.

Here’s a sample: “Electric Dreams Episode 1 The Hood Maker”.

… The Short Story: Published in 1955, ‘The Hood Maker’ was—like the majority of Philip K. Dick’s work—incredibly prescient of the world we now live in. It opens with a scene of an old man attacked on the street by a crowd. The reason? He’s wearing a hood that blocks his mind from telepathic probe. One of the crowd cries out: “Nobody’s got a right to hide!” In today’s world where we seem happy to ‘give away’ our privacy to Facebook or Google in return for access, the world of Philip K. Dick’s hood maker is not all that alien….

The Television Episode: In bringing ‘The Hood Maker’ to television, screenwriter Matthew Graham faced a challenge. The material would obviously have to be expanded to fill an entire 50-60 minute episode of television, but exactly how that expansion was realized could make or break the show. The television version of ‘The Hood Maker’ is, as a result of that expansion, a mixed success.

Richard Madden stars as Clearance Agent Ross (using his natural Scottish accent, for a welcome change), while Holliday Grainger is the teep, Honor, assigned to him as a partner with special skills. This is a world, visually and conceptually, that is reminiscent of Blade Runner. Madden is dressed and acts like a cut-rate Rick Deckard, while the shanty towns, marketplaces, and urban environments (some shot in the Thamesmead estate made famous by Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange—instantly recognizable, despite an attempt to hide it through all the murky cinematography and constant rain) all recall scenes from the first ever Philip K. Dick big screen adaptation. It seems, as ever, that any take on Dick’s work has to somehow pay homage to the foundation text of Blade Runner….

(6) BETANCOURT NEWS. John Betancourt has launched a membership ebook site at bcmystery.com (to go with their new Black Cat Mystery Magazine).

The model is subscription-based: for $3.99/month or $11.97/year, you get 7 new crime and mystery ebooks every week. We’re going through the Wildside Press backlist (currently about 15,000 titles) and digitizing new books from estates I’ve purchased. Wildside owns or manages the copyrights to 3,500+ mysteries. For example, this year I purchased Mary Adrian’s and Zenith Brown’s copyrights (Zenith Brown published as Leslie Ford and David Frome — she was a huge name in the mystery field in the 1950s and 1960s.)

(7) HE DIDN’T GO THERE. Did John W. Campbell kill his darlings? Betancourt reports discovering a new segment of a famous old science fiction classic:

Of SFnal interest, an early draft of John W. Campbell’s “Who Goes There?” has turned up amidst his papers. It’s 45 pages longer (!) with 99% of the new material taking place before the events in the classic story. I’m discussing what best to do with it with my subrights agents. I’m thinking of publishing it myself as a 200-copy limited hardcover edition.

(8) TODAY IN HISTORY

- November 8, 1895 – X-rays discovered

- November 8, 1969 – Rod Serling’s Night Gallery aired its pilot episode.

(9) TODAY’S BIRTHDAY BOY

- Born November 8, 1847 – Bram Stoker

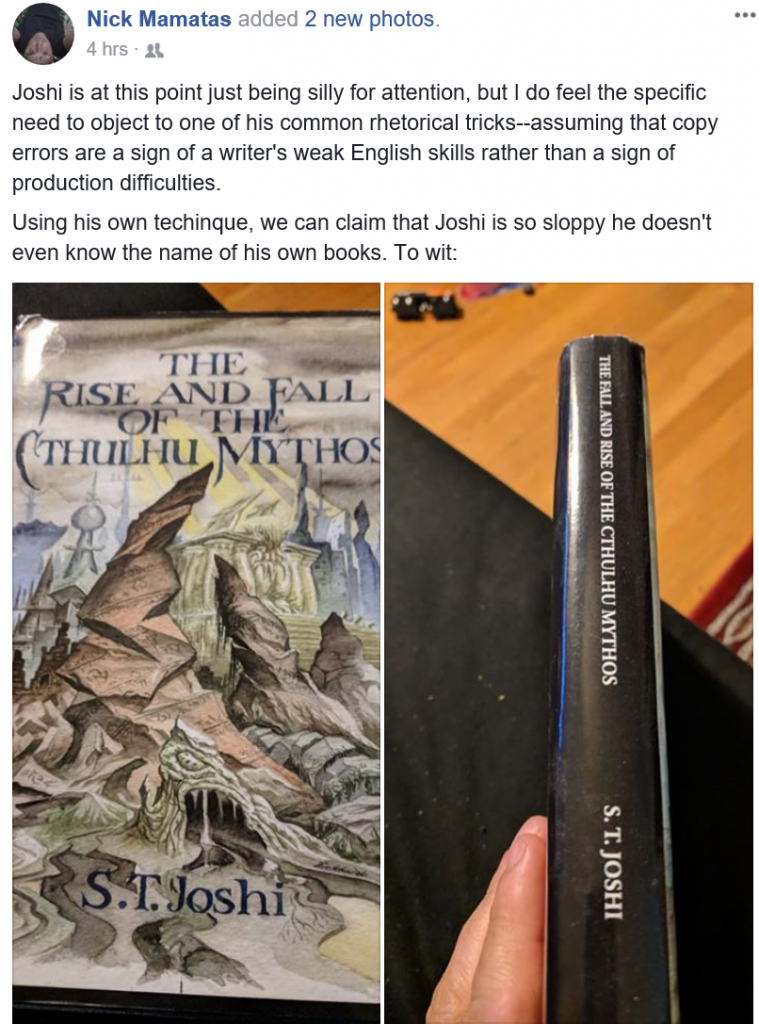

(10) THE VIEW FROM INSIDE THE GLASS HOUSE. S.T. Joshi devoted 5,600 words to ripping the work of Brian Keene, as reported here the other day, leading to this priceless observation by Nick Mamatas:

(11) LTUE BENEFIT ANTHOLOGY. The annual Life, the Universe, & Everything (LTUE) academic symposium has been a staple of the Utah author community for decades. LTUE helps students of all ages by providing them with greatly discounted memberships. So that practice may continue, Jodan Press—in conjunction with LTUE Press—is creating a series of memorial benefit anthologies.

The first will be Trace the Stars, A Benefit Anthology in Honor of Marion K. “Doc” Smith. It will be edited by Joe Monson and Jaleta Clegg, and they have put out a call for submissions.

Trace the Stars, is a hard science fiction and space opera anthology created in honor of Marion K. “Doc” Smith. Doc was the faculty advisor to the symposium for many years before his passing in 2002. He had an especially soft spot for hard science fiction and space opera. From his nicknamesake, E.E. “Doc” Smith to Orson Scott Card, and Isaac Asimov to Arthur C. Clarke, these tales inspired him. This anthology will contain stories Doc would have loved.

We invite you to submit your new or reprint hard science fiction or space opera short stories to this anthology. Stories may be up to 17,500 words in length. Those wishing to participate should submit their stories to [email protected] by July 31, 2018. Contracts will be sent to those whose stories are accepted by September 30, 2018. Stories not accepted for this anthology may be considered for future benefit anthologies for LTUE. The anthology is projected to be released during the LTUE symposium in February 2019 in electronic and printed form.

As this is a benefit anthology, all proceeds beyond the basic production costs (such as ISBN and any fees to set up distribution) will go toward supporting the symposium in its goals to inspire and educate authors, artists, and editors in producing the next generation of amazing speculative fiction works.

(12) MONSTROUS BAD NEWS. Dangerous games: “Caught Up In Anti-Putin Arrests, Pokemon Go Players Sent To Pokey”.

To be sure, Sunday’s arrests at Manzeh Square near the Kremlin are serious business: Authorities say 376 people described as anti-government protesters linked to the outlawed Artpodgotovka group were rounded up. The group’s exiled leader, Vyacheslav Maltsev, called the protest a part of an effort to force President Vladimir Putin to resign.

“We showed them that we’re all really trying to catch Pokémons. Police asked us why we all gathered together. One of us answered. ‘Try catching it on your own,'” one player, identified as a 24-year-old history studies graduate named Polina, told The Moscow Times.

What we might call the “Pokémon 18” now faces court hearings next week on charges of violating public assembly rules. The infraction carries a fine of 20,000 rubles ($340), according to the newspaper.

"Revolution" circa 2017: One of the protesters detained outside the Kremlin is catching Pokemon in the police van. Via @mynameisphilipp pic.twitter.com/EXysWjHsry

— Alec Luhn (@AlecLuhn) November 5, 2017

(13) A STITCH IN TIME. The BBC profiles another set of women who make significant contributions to the space program in “The women who sew for Nasa”

Without its seamstresses, many of Nasa’s key missions would never have left the ground.

From the Apollo spacesuits to the Mars rovers, women behind the scenes have stitched vital spaceflight components.

One of them is Lien Pham, a literal tailor to the stars – working in the Jet Propulsion Laboratory’s shield shop to create thermal blankets, essential for any spacecraft leaving Earth.

It may not sound glamorous, but Lien does work with couture materials.

The Cassini mission, her first project at Nasa, went to Saturn cloaked in a fine gold plate for durability over its 19-year journey.

(14) RECOGNIZABLE TRAITS. Sarah A. Hoyt’s survey of the characteristics of various subgenres of science fiction is interesting and entertaining — “Don’t Reinvent The Wheel”. Here are a few of her notes:

Hard SF comes next. It’s usually — but not always — got some element of space. Even if we’re not in it, this change whatever it is, relates to space. Again, not always, but the ones that sell well seem to have this. I’ve talked a bunch about the genre above, so no more on it need be said.

Next up is Time Travel science fiction. This differs from time travel fantasy in that the mechanism is usually explained in science terms, and from time travel romance in that there are usually (but not necessarily) a lot fewer hot guys in kilts. Either the dislocated come to the present, or we go to the past. Your principal care should be that there should be a semi-plausible mechanism for time travel, even if it’s just “we discovered how to fold time” and if you’re taking your character into historic times, for the love of heaven, make sure you have those correct. My favorite — to no one’s surprise — of these is The Door Into Summer which does not take you to past times. Of those that do, the favorite is The Doomsday Book by Connie Willis. My one caveate, re: putting it on Amazon is for the love of heaven, I don’t care if you have a couple who fall in love, do not put this under time travel romance. Do not, do not, do not. You know not what you do.

Next up is Space Opera — my definition, which is apparently not universal — Earth is there (usually) and the humans are recognizably humans, but they have marvels of tech we can’t even guess at. The tech or another sfnal problem (aliens!) usually provides the conflict, and there’s usually adventure, conflict, etc. My favorite is The Moon Is A Harsh Mistress. (And by the knowledge of his time I think it was hard SF except for the sentient computer which we STILL don’t have. Yes, I cry when Mycroft “dies” What of it?)

(15) POPPYCOCK. Shaun Duke is touchy about the notion that there is such a thing: “On the “Right” Kind of Reviews”.

One of the things that often bothers me about the reviewing process is the idea that some reviews are inherently more valuable than others. By this, I don’t mean in the sense of the quality of the writing itself; after all, some reviews really are nothing more than a quick “I liked it” or are borderline unreadable. Rather, I mean “more valuable” in the sense that different styles of reviewing are worth more than others. While I think most of us would agree that this is poppycock, there are some in the sf/f community who would honestly claim that the critical/analytical review is simply better than the others (namely, the self-reflective review).

Where this often rears its head is in the artificial divide between academia and fandom-at-large (or “serious fandom” vs. “gee-golly-joyfestival fandom”). I don’t know if this is the result of one side of fandom trying desperately to make sf/f a “serious genre” or the result of the way academics sometimes enter sf/f fandom1. But there are some who seem hell bent on treating genre and the reviews that fill up its thought chambers as though some things should be ignored in favor of more “worthy” entries. I sometimes call these folks the Grumble Crowd2 since they are also the small group of individuals who appear to hate pretty much everything in the genre anyway — which explains why so much of what they do is write the infamous 5,000-word “critical review” with nose turned up to the Super Serious Lit God, McOrwell (or McWells or McShelley or whatever).

(16) ICE (ON) NINE. Amazing Stories shared NASA’s explanation about “Giant Ice Blades Found on Pluto”, our (former) ninth planet.

NASA’s New Horizons mission revolutionized our knowledge of Pluto when it flew past that distant world in July 2015. Among its many discoveries were images of strange formations resembling giant blades of ice, whose origin had remained a mystery.

(17) MARVEL’S LOCKJAW. Call me suspicious, but I’m inclined to be skeptical when I see that the author of a comic book about a dog is named “Kibblesmith.”

He’s been a breakout star since he could bark, a faithful sidekick to his Inhuman masters, and has helped protect an empire. Now, he’s got his own mission to take on — Marvel is excited to announce LOCKJAW #1, a new four-part mini written by Daniel Kibblesmith with art by Carlos Villa.

When Lockjaw finds out his long-lost siblings are in danger, he’ll embark on a journey which will result in a teleporting, mind-bending adventure. “We’re super excited about this book. Daniel Kibblesmith—a hilarious writer who works on The Late Show and recently published a book called Santa’s Husband—has cooked up an incredibly fun, heart-filled romp around the Marvel Universe,” said series editor Wil Moss. “Back in BLACK BOLT #5, writer Saladin Ahmed and artist Frazer Irving finally settled the mystery of Lockjaw’s origin: He’s definitely a dog, birthed by a dog, who happens to have the power of teleportation. But now we’re going even further: How did Lockjaw obtain that power? And is he really the only Inhuman dog in the universe? So in issue #1, we find out that Lockjaw’s got brothers and sisters. From there, we’ll be following everybody’s best friend around the universe as he tracks down his siblings—along with a surprising companion, D-Man! It’s gonna be a fantastic ride, all beautifully illustrated by up-and-comer Carlos Villa! So grab on to the leash and come with!”

You heard us: Grab a leash, prepare your mind, and teleport along with Lockjaw when LOCKJAW #1 hits comic shops this February!

(19) ANOTHER OLD NEIGHBORHOOD. See photos of “The birth, life, and death of old Penn Station” at NY Curbed. Andrew Porter recalls that the hotel across the street from the station was the site of numerous comics and SF conventions, including the 1967 Worldcon and SFWA banquets, etc. Porter says:

The Pennsylvania Hotel was built directly across the street, to capture the trade of those using the Pennsylvania Railroad to get to NYC. At one time, the hotel had ballrooms (replaced with TV studios), swimming pools, etc. Renamed the Statler-Hilton in the 1960s, re-renamed the Pennsylvania Hotel in recent decades. The hotel’s phone number remains PEnnsylvania 6-5000, also a famous swing tune written by Glenn Miller, whose band played there before World War Two.

The current owners of the hotel planned to tear it down, replace it with an 80-story office building (shades of Penn Station!) but those plans fell through a couple of years ago.

[Thanks to John King Tarpinian, JJ, Cat Eldridge, Martin Morse Wooster, Chip Hitchcock, Carl Slaughter, and Andrew Porter for some of these stories, Title credit goes to File 770 contributing editor of the day Peer.]

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

George is a Targaryen. I knew it.

(14) “The Moon is a Harsh Mistress” as space opera? That’s not the Heinlein I would pick as space opera (I’m not sure I’d pick any Heinlein as space opera – “space opera” (afaik) was not a big part of the field while Heinlein was at his peak (though I suppose “Have Spacesuit, Will Travel” is space-opera-ish – easy interstellar (extragalactic!) travel, lots of aliens, vile villains, and the fate of all humanity depending on a couple of plucky kids))

(2) Ruud Mechanicals! I can’t believe I missed that pun when I was reading Ironclads.

“My illegal third child is the Student of the Month at the Battle School”

14) In literary fiction there is a subgenre of utopian literature – books about a hypothetical utopian society, Plato Republic being the most famous. I would classify The Moon is a Harsh Mistress as belonging to the subgenre of Utopian Scifi. Another example would be Dispossed.

My pixel is the scroll of the month at Godstalk.

And the Marvel “Inhumans replace X-Men” corporate directive disaster ends as it should, with the only likable Inhuman character – the dog – getting a series.

(14) — I’d say Citizen of the Galaxy is relatively space opera-ey. Moreso than Moon, much as I enjoyed it. I agree that Have Spacesuit, Will Travel also fits the bill; and I wonder if a case could be made for The Star Beast?

@bookworm1398: ISTM that Utopian works are primarily about the ideal(ized) society; tMIaHM is about the process of getting there. A rather large amount of SF could be classified as Utopian if this work is.

Ah yes, Dispossed — the story of a sheriff whose posse went thisaway when he went thataway. (Not mine — from an F&SF contest at least 40 years ago.)

(12) MONSTROUS BAD NEWS.

I am so glad to be in a country where playing Pokemon doesn’t get you arrested.

(14) RECOGNIZABLE TRAITS.

I confess that I haven’t bothered clicking through, though I am curious to know if she used taverns to signify specific (sub)genres.

19) Just one more example which proves that the demolition mania of the 1950s, 60s and 70s did much more damage to architecture than WWII.

14) Uh, has she read anything other than Heinlein? Okay, so she does mention Lois McMaster Bujold and Clifford Simak at one point, but otherwise her examples are Heinlein, Heinlein and more Heinlein.

I would think it needed more swanning about in spaceships to be space opera. Instead, it had a more realistic view of space travel and the effect of low-gee living on returnees to Earth, as I recall.

CITIZEN OF THE GALAXY has extended space opera sections, at least.

But most of the books set within the solar system don’t feel that space-opera-ish to me. Space travel is travel, and it’s fairly utilitarian, not the romantic outer-space swashbuckling of classic space opera. Even, say, STARMAN JONES, STARSHIP TROOPERS and TIME FOR THE STARS don’t feel like space opera — they’ve got the space but not the opera.

On the other hand, “The Scourge of the Spaceways,” within THE ROLLING STONES, that’s clearly space opera.

Andrew:

I was surprised at this one too. I thought Space Opera was more outer space and space ships.

“File770, book recommendations at the speed of a scrolling pixel!”

14: she mentions Heinlein’s “sensitives” and uses that to place the works in “space opera”, or at least not in “:hard sf”…except that concept was based, as was much of the “special talent” stuff, on serious work that was being done at universities and government research labs; at the time of writing, much of this stuff was straight extrapolation of the scientific research being conducted.

I belong to the school of thought that says you classify a work of science fiction within the context of its time, which means that anything written prior to (arbitrary but close) 1985 is classified as SCIENCE FICTION. (After that date publishers began paying attention to newly minted MBA types caught up in the fever dream of marketing metrics – which don’t really fit works that are both science fiction and fantasy, hence, the distinct lack of such works until recently) (Would Dhalgren have been published today? What niche does that novel fit into?)

That’s it…from Asimov to Zelazny, regardless of their style, subject or theme, they all wrote SCIENCE FICTION, full stop. No arbitrary, marketing-niche derived sub-genre bullshit. We could just as easily refer to Starship Troopers as “political” SF, Skylark of Space as the inaugural SF Romance, The Dragon Masters as Genetic SF…The Martian Chronicles as “Fantasy masquerading as SF”.

(Have Spacesuit Will Travel has detailed and accurate descriptions of orbital mechanics, of spacesuit engineering…how is this “space opera” rather than “hard sf”?)

Do you think it’s Science Fiction? You do? Point at it. Go ahead, point a finger at it. It’s SF.

more: there are actually TWO sub-genres of Science Fiction. They are:

Good Science Fiction

Bad Science Fiction

and of course Science Fiction that straddles those two sub-genres.

@steve davidson: Classifying things in the context of their time makes sense in terms of “was this plausible extrapolation from the science of the time?” That covers at least some pre-Mariner stories set on Mars, even though they don’t fit with what we now know about Mars.

But I don’t buy what you seem to say here, that nothing from before the mid-1980s counts as fantasy rather than SF. Easy examples: both The Lord of the Rings and A Wizard of Earthsea are clearly fantasy rather than science fiction.

Yes, there are weird edge cases: we seem to have agreed to allow all sorts of handwaving and phlebotinum to justify FTL travel and, often, time travel, and not always by connecting the two. But the fuzziness of some categories (as you allude to Damon Knight) doesn’t make pre-1985 fantasy a subset of science fiction. If anything, it’s the other way around, with different kinds of nonexistent or impossible things. (I think it was Algis Budrys who argued that sf is a subset of fantasy, which in turn is a subset of children’s literature.)

Various things:

a. There’s a difference between subgenres (or indeed genres) as a tool for comparison and criticism, and subgenres as a means of – I would say marketing, but that sounds like something men in suits do, which isn’t exactly what I mean – a basis of recommendation, perhaps, a focus for a community of readers. Subgenres of SF in the first sense might include Time Travel Story or First Contact Story. Subgenres in the second sense would include Epic Fantasy, Urban Fantasy, MilSF, Alternate History and Steampunk. Any body of literature will contain subgenres of the first kind. I’m inclined to agree with Steve that Science Fiction didn’t acquire subgenres of the second kind until relatively recently. (I take it he isn’t trying to say that Fantasy wasn’t a distinct thing.) There are also still plenty of works that don’t fit neatly into any of these categories. (I don’t see either Hard SF or Space Opera as subgenres of this kind – they are rather points on a scale, indicating a quality you can have more or less of.)

b. I’m fairly sure people did talk about Space Opera in Heinlein’s time; I think it was originally meant to contrast with stuff that didn’t contain any serious scientific content, but just used space as a background for adventure, romance or whatever. Now it often seems to be used just to mean ‘set in space’, with the consequence that the same works are frequently described both as Space Opera and as Hard SF, when in the olden days they were more often contrasted. (Not that there aren’t edge cases – there always are for any classification – but now it’s not clear that even the central works of the two areas are being distinguished.)

c. And ‘Hard SF’ is itself multiply ambiguous, with some people insisting it should be scientifically accurate, while others use it for any work that’s based on following out a scientific hypothesis, however weird. (And works where the science is weird are often the ones where it’s most central.) And it’s also used in vaguer ways, e.g. in the Tor.com ‘Best Books of the Eleven Year Decade’ poll, where, as I’ve mentioned before, it was used to cover almost anything you’d naturally call Science Fiction.

@Vicki Rosenzweig: fantasy was entirely outside of what I was discussing.

I understand the confusion; I meant to refer to anything science fictional from 1985 and earlier, leaving the class of fantasy entirely out of the equation.

I believe that Budrys was discussing standardized literary classifications, something like –

Fiction – sub-class Fantasy – sub-sub class Science Fiction

but then that’s very broad (and it would be less confusing if it were named something else, such as non-realism, so that at least we aren’t forced to make “fantasy” a sub-genre of “Fantasy”)

I’ll also take issue with your classification of FTL and Time Travel as fantastical elements: the Alcubierre drive or something like it has not been ruled impossible, and the door remains open for limited time travel (into the past) as well. So long as they have not been ruled out by science, they are not magical.

Hoyt’s categories are weirdly specialized. For instance, her “space colony or planetary exploration sub-genre” is about as close as she gets to planetary romance or ecological SF, but the description seems too narrow for things like A Door into Ocean, Golden Witchbreed, or Grass.

@Andrew M: Space Opera was most definitely a term of opprobrium…pretty much sitting side-by-side with “Skiffy” (sci-fi); westerns with six-guns replaced with blasters, spaceships instead of wagon trains, Mars or Venus instead of the wild west.

For me, it is very telling that Roddenberry supposedly presented Star Trek to network executives as “wagon train to the stars”, because he was talking to an audience that only knew “skiffy”, talking down to them (without their knowledge) with the very apt variation of space opera/horse opera. Star Trek was of course very much NOT space opera (in its day), nevertheless, Roddenberry reached for a description that reflected the very worst kind of SF, because that would have been the only kind of SF the execs would have understood. It’s also indicative of how nasty the space opera association was within SF circles.

I came to understand that term early in my reading career and it still turns my head when I see it used as a term of endearment and praise.

Yes, sorry, that should have been ‘contrast with Hard SF, and mean stuff that didn’t contain…’,

@Vicki Rosenzweig: I think what steve davidson is saying is that there were no hybrid works prior to the mid-80s because the classification didn’t exist yet. I don’t agree, and I think his blaming of market fragmentation on an influx of market-driven professionals is some weak sauce (I mean, come on, SF has always been mercenary as all hell, it was just ad-hoc rather than organized), but I think classifying a work based on where it would have fallen when it was published has some value (making retroactive classifications also has value, depending on what you’re trying to talk about). If you want less hyperbole, you can very quickly learn that “space opera” as a sub-genre descriptor goes back almost 80 years, and was initially pejorative, though by the ’70s it was simply descriptive.

@steve davidson: Dhalgren absolutely would be published today–by a mainstream press, because an SFF press wouldn’t touch it with a ten foot pole. And people would be arguing about whether or not Delany was just another tourist.

(14) It wouldn’t have occurred to me to call The Moon is a Harsh Mistress space opera either, but I don’t find it the least bit operatic in either tone or scope. It’s a small-scale Atlas Shrugged as narrated by Yakov Smirnov. Nor would I consider it a utopian fiction, though I imagine Heinlein probably thought of it that way. It looks dystopian af to me. I’d rather live in Gibson’s Sprawl.

(15) I have only two beefs with this. First: “I liked it” isn’t a review; it’s an opinion, and a valid one, but that’s only part of what a review is–a review also tells you why. It doesn’t need to be long or deep or academic, but it does need to explain the opinion to some degree, not just express it (“I liked it because…”). A professional review needs to do more, but I’m not of the opinion that reviews by people who aren’t professional critics/reviewers need to look like professional reviews, nor am I of the opinion that professional reviews are the only ones with value. (And professional reviews come in different flavours: I write both self-reflective and analytical reviews in professional contexts, depending on what struck me as most important about the book or about what interested me in the book.)

Second: criticism and reviewing aren’t the same things, and they are conflated here. Reviews contain value judgements about about a book, and seek to answer questions about whether or not a work is good or bad, beautiful or ugly, things like that. Criticism doesn’t care if a book is good or bad, beautiful or ugly (or rather, modern criticism doesn’t; in the early days when my grandfather was a young man that was very much considered the province of criticism, but that hasn’t been true since my father was young). Criticism cares about how the book works. It wants to know about how it’s structured, how the elements interact with each other, what social/philosophical assumptions are made and what ideas it challenges or what point of view it supports or stands in opposition to, how it relates to other books, and so on. Erik Davis has made an extremely strong case that writing–not just the act, but the result–is a technology, and books are in that sense machines. Reviews tell us if we like those machines, or if they are useful or pleasing to us in some way. Criticism tells us how the machines work* (or more frequently how some part of them works).

*Seeks to tell us, anyway.

@August: no, you are missing my point entirely. Leave fantasy out of the equation. This has nothing to do with fantasy. Yes, there are works that could be called “science fantasy” (if you want to resort to the sub-genre crap).

What I am saying is: employing Damon Knight’s definition of SF (what we point to when we say SF), we do not need sub-genres; in times past, earlier than 1985, anything that got pointed at was classed as “science fiction”…not “Hard SF Science Fiction” or “Space Opera Science Fiction”; just plain, old, widely encompassing “Science Fiction”

There was fantasy…LoTR, Fafhrd, Conan, Donaldson, etc…, classified as fantasy; there was some SF that some readers questioned its sfnalness (but at least some fingers pointed at it, so – SF). The divide is clearly science & general logic vs non-science and internal logic, with SF in all its iterations falling on the side of the former. Edge cases, certainly, always are…but read what I wrote with the assumption that we are only talking about works that have already been identified as Science Fiction and nothing else.

Good morning!

There is Sun. Stuff, including necessary daily meds, and solid food, are staying down.

I am headed out into the sunlight.

Today, one way or another, I will get chicken noodle soup.

Glad you are feeling better, Lis! Enjoy the sunlight. 🙂

Lis Carey, may the Quest for the Soup of Chicken Noodle be successfully completed.

I would have thought Sir Thomas More’s Utopia would be the most famous Utopian novel. I guess it’s better than them being called Republican novels.

Twitter seems abuzz with the death of Mjølnir. I keep pointing out that it was surely an imposter as its handle was much too long. Did Marvel ever cover its creation in the comics?

Yes, MGC is the “Always mention Heinlein” blog.

File770, on the other hand, is the “Always mention Bradbury” blog.

In those olden days (some of which I lived through) there was already a boundary-crossing category called “science-fantasy.” There was even a UK magazine of with that title, though it might have been intended to signal an intermingling of SF and F stories, in much the same way F&SF‘s name did. But before that, Campbell’s Unknown Worlds published stories that mashed up SF and F motifs–notably from Heinlein, de Camp & Pratt, Jack Williamson, and Fritz Leiber–and in the mid-1940s Jack Vance was writing the Dying Earth stories that were published in 1950. This kind of pan-fantastic/mixed-motifs spectrum has been recognized for my entire reading life.

There’s a whole other conversation worth having about what “genre” means in various contexts, and the difference between rigorous and loose uses of the term, but that might be tedious and inappropriately pedagogical. I’ll just say that every time I read a Wikipedia entry that touches on genre matters, I have to suppress the urge to grab a piece of chalk and start drawing diagrams.

@ Steve Davidson: One might find it useful to look up various categorical terms (e.g., hard science fiction, space opera, science fantasy) in the excellent jessesword.com lexicography site. The citations indicate when the terms appeared in print and offer contextual hints as to how they were used.

I do find it interesting that the parallel worlds novel Transition was sold as Iain M Banks’ SF in the US and as Iain Banks’ mainstream fiction in the UK.

At last someone who recognizes this heinous fraud.

Paradigmatic authors?:

MCG- Heinlein

File770 Posts – Bradbury

File770 Comments – LeGuin

Castalia House – Burroughs

JCW – A. E. van Vogt

And So Pixels Made of Sand Scroll into the Sea, Eventually.

I vigorously dispute @steve davidson’s assertion that there was no differentiation before 1985; I think Heinlein would have been rightfully annoyed at being considered in the same bin as Doc Smith. (People who think of older work as homogeneous are amazed to find that the operatic Lensman books were first published 1948-1954.) And there certainly was division, even if there was so little work that people would read most of what was published just to get their fix; similarly, “hard science fiction” (e.g., Astounding) was seen as separate from social SF (e.g., Pohl, Sturgeon, and other mostly-Galaxy writers), not to mention what-do-you-call-Delany. That editors saw differences was clear when I researched a paper on definitions of SF for my high-school English class — in 1970. It’s true that all of those could be covered by “science fiction” — but so can all of them be today; I think people may be more likely to talk about classification because there’s so much available that fast readers can still be picky, but the arguments about “Is it science fiction” go way back.

I also doubt

. “Space opera” was deprecated in the 1950’s (see Blish and Knight); Fancyclopedia claims that “sci-fi” was disliked as soon as it appeared, but I recall a fannish essay treating the term as newly execrable — and I wasn’t reading anything fannish before 1973. It was certainly being used by ignorant outsiders — the type specimen, possibly apocryphal, is the CBS exec telling Roddenberry “We don’t need another sci-fi series; we have Lost in Space!” — but I don’t think it was universally deprecated; I’ve already had to get an unwarranted credit out of my Fancy bio, so I don’t consider them reliable — especially on dates before the editors became active. (Anyone who has an original Fancyclopedia 2 should chime in; the online claims to have absorbed it, but doesn’t make clear what was absorbed vs what is new.)

(*) I remember reading what I think was the first essay deprecating “sci-fi”, in some fannish print; I wasn’t reading any such until 1973.

@Chip Hitchcock

The Lensman series was first published in book form from 1948 through 1954, but the Lensman novels (starting with “Triplanetary”) were published in magazine form starting in 1934.

(3) BREAKTHROUGH ARCHEOLOGY. – Wow, that is cool. Any history-oriented Filers have ideas about how that could have been done? My understanding is that lenses weren’t used/created for another several hundred years after that piece was etched.

File770 Comments – P.C. Hodgell (surely?)

Good point. When LASFS dropped out of the Science Fiction League in the late 1930s, the new name of the club became the Los Angeles Science Fantasy Society.

Whereas for every other -SFS club, the SF stands for science fiction.

bookworm1398 on November 8, 2017 at 8:16 pm said:

The moon in TMIAHM is a prison colony with harsh living standards. It may be seen as a Libertarian Utopia but I don’t consider it a Utopia at all.

I know some people, possibly including the author, class The Dispossessed as an SF Utopia. I do not consider a book where half the story takes place in an oppressive capitalist dystopia and most of the other half concerns a civilization trying desperately for years to avoid starving to death, and where individual thought is collectively smothered, as any kind of Utopia.

@Camestros Felapton:

Surely it’s Niven/Pournelle. It’s mostly Hoyt that’s got Heinlein going on.

@ULTRAGOTHA: Le Guin’s subtitle for The Dispossessed was ‘An Ambiguous Utopia’, which has always struck me as intentionally ironic.

@ Ultragotha: I wouldn’t choose to live in either of those societies either, but that’s not the point. Both books talk about a society organized with significant differences from the current one, mention how the people are socialized into accepting those mores and what the advantages and weaknesses of those societies are. You may not find the arguments convincing, but that doesn’t make them not Utopian SF – just as you wouldn’t say the Ramayana is not a religious text because you don’t believe in it.

That’s not what “utopia” means, though. It can’t just be a “different” society, it has to be an ideal one. That’s why More chose the word “utopia” (“no-place”, or “the place that cannot be”, if you prefer) in the first place.

I think Le Guin was showing us what idealized, and therefore utopian, capitalist and (anarcho) communist societies would look like, but also pointing out that by our current standards the “goodness” of neither society is absolute; there is ambiguity in the tradeoffs they have to make for each society to function.

Yay, title credit!

I think subcategories are handy when discussing work, especially things like tone, target audience and setting. You would usually not find magic or cyberspace in space opera.

But you could find them, because its just that: a handy tool. Try to set boundaries on them is moot, because a)there will always be grey zones, b) SF itself is a pretty wobbly term and c) why would you? If a novel breaks the expectation of its subcategory its noteworthy because of that. Trying to fit it in somewhere else is missing the point.

We are twelve pixels from hell and will scroll all over your little town!

I have enjoyed the sunlight.

I have captured the elusive chicken soup.

There are books to read, and a dog who legit qualifies as an SJW credential to cuddle with.

Life is good.

While Our Good Host certainly takes every opportunity he can to report Bradbury-related news, that’s not quite the same as injecting Bradbury into every vaguely-sfnal discussion.

And yeah, Hoyt’s definition of “space opera” looks extremely idiosyncratic (but she does sort of acknowledge that), but if that and a mild obsession with Heinlein are the worst things I can find in one of her essays, then I’m certainly not going to complain.

“The Scroll Is A Harsh Pixel”?

(someone must have used that one already)

Are there really any Utopian novels? There are books about utopias – The Republic, More’s Utopia, Bacon’s New Atlantis, Wells’s A Modern Utopia – but they tend not to be actual stories as such: in a utopia (as envisaged by the author) nothing much could really happen. (You could have a story about the adventures of some individuals against the background of a utopian society, but I don’t think that’s what ‘utopian fiction’ is normally taken to mean – that wouldn’t be its genre.)