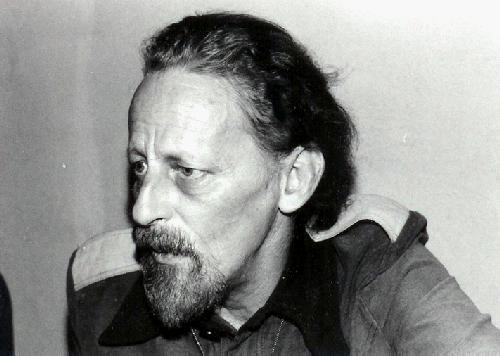

By John Hertz: (reprinted from Vanamonde 1333) It’s the centennial year of Theodore Sturgeon. Let us salute him.

He left seven novels, one published posthumously; two hundred shorter stories, republished in two dozen collections, then fully in The Complete Stories, thirteen volumes 1995-2010, a labor of love – I use the word deliberately – by Paul Williams, Debbie Notkin, Noël Sturgeon, Harlan Ellison, and a host of others.

Hundreds of book reviews, for Galaxy, Venture, Twilight Zone, National Review, The New York Times, and Hustler while Paul Krassner was editor, are so far uncollected.

The sounds above open “The Man Who Lost the Sea” (1959), title tale of Complete Stories vol. 10, whose editor found it apparently the first science fiction chosen for The Best American Short Stories (i.e. 1960).

Best was edited 1941-1977 by Martha Foley (1897-1977), whose magazine Story had introduced J.D. Salinger, William Saroyan, Tennessee Williams, and in 1938 gave first prize to Richard Wright; Best had previously introduced Sherwood Anderson, Edna Ferber, Ernest Hemingway; Foley’s own first story, published in the Boston Girls’ Latin School magazine, was “Jabberwock”.

An Ellison story was in the 1993 Best (“The Man Who Rowed Christopher Columbus Ashore”; the oceanic coincidence does not seem substantive, although Robert Bloch, who like Ellison was both a fan and a pro, said Ellison was the only living organism he knew whose natural habitat was hot water).

Ellison wrote the foreword to Collected Stories 11, which volume includes one they co-authored (see Partners in Wonder, 1983), a Western co-authored with Don Ward, two from mystery-fiction magazines, and one from Sports Illustrated.

In 1952 Sturgeon said a good science fiction story was one “built around human beings, with a human problem, and a human solution, which would not have happened at all without its scientific content”. That was before “The [Widget], the [Wadget], and Boff” (1955) – which one of our finest editors, Anthony Boucher, put into one of our finest anthologies, A Treasury of Great Science Fiction (vol. 1, 1959). Come to think of it –

In theory science fiction and fantasy are distinct. In practice – well, I don’t want to decide whether, say, “Seasoning” (1981), which I apparently rate higher than the editor of Collected Stories 13, is science fiction or fantasy, or in what sense we are to suppose the two characters know what is happening at all.

“Yesterday Was Monday” (1941) must be fantasy. But another of our finest editors, Groff Conklin, chose it to open another of our finest anthologies, Science Fiction Adventures in Dimension (1953). It’s been translated into Dutch, Finnish, French, German, and Japanese, and reprinted two dozen times. Its protagonist, and other characters, don’t know what’s happening.

In “The Skills of Xanadu” (1956), another candidate for Sturgeon’s best, the protagonist doesn’t know what’s happening. Everybody else knows.

The title character of “The Comedian’s Children” (1958) – another candidate – is the only one who does know what’s happening. If the protagonist of a story is the one who changes, that may be Nobel Prize scientist Iris Barran; she finds out. This is a transformation story. We transform. There is a bad guy. If his immense talent were not genuine, there would be no story. Is he sympathetic? Well –

Sturgeon also said Science fiction is knowledge fiction. If the best puns resonate in each meaning, this is one of our best. Consider the Latin root of science.

Robert Heinlein (Collected Stories 3, p. 367; from his 1985 introduction to Godbody): “Mark Twain said that the difference between the right word and almost the right word was the difference between lightning and lightning bug. Sturgeon did not deal in lightning bugs.”

Isaac Asimov (v. 3, p. xi): “He had a delicacy of touch that I couldn’t duplicate if my fingers were feathers.” Connie Willis (vol. 12, p. ix): “he was writing about different things…. problematic, dangerous … ultimately tragic…. in a simple … style…. Like Fred Astaire, Theodore Sturgeon made it look easy.”

Samuel Delany (v. 2, p. x): “The range of Sturgeon’s work is a … galaxy of … dazzling and precise lights shining out against … ordinary rhetoric…. the single most important science fiction writer during the years of his major output – the forties, fifties, and sixties.”

Ellison (v. 11, p. xiii): “He could squeeze your heart till your life ached.”

Horace (The Art of Poetry, l. 143 – two millennia ago): “His thought is not to give flame first and then smoke, but from smoke to let light break out.”

Sturgeon became fond of Ask the next question, and used as an emblem a Q with an arrow through it. I never asked him about Ask the previous question.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

John Clute: “Sturgeon’s stories… give off a sense that something terrible must have happened long ago, almost certainly to Sturgeon himself…They are like the residues of some terrible accident, one of those mass pileups on the interstate only visible from the CNN helicopter, anguished Edvard Munch faces turned up to the television cameras trying to convey something.”

https://www.salon.com/2000/11/15/sturgeon/

Someone needs to do a proper evaluation of Sturgeon as a queer writer, I think, among the many things he was.

I remember the feeling of shocked epiphany when I heard that Vonnegut’s Kilgore Trout was Theodore Sturgeon. “What…? But of course it was, why didn’t I see that?”

I recall talking to Larry Janifer about Sturgeon and how he upset a few marriages in the 1950’s when he lived in New York by seducing the husbands.

The title slips my mind, but Sturgeon had a short story in Paul Krassner’s THE BEST OF THE REALIST that was not in his “complete” collection”.

John quotes from the Harlan Ellison introduction to volume 11, and it’s a favorable quote, but overall that is an extremely ungenerous essay, with Ellison saying he felt required to tell the ugly truths about Sturgeon that no one else was saying in their introductions. I don’t remember anything of what he said, and I’ll never read it again.

Clute says that Sturgeon’s stories give off a sense that something terrible happened…..

I don’t know what Clute was seeing, but Argyll is a memoir by Sturgeon about his horribly abusive father.

I just reread The Dreaming Jewels and it’s got an utterly harrowing description of workplace harassment that I didn’t even notice when I was a kid. I noticed the jewels in the dark, and the kid eating ants, and the guitar playing….

I wouldn’t presume to say what Sturgeon was fundamentally talking about. People used to say Sturgeon knew all about love and I was never sure about that– but he did seem to be an expert on hate.

I do recommend reading or rereading more Sturgeon.

“The Man Who Lost the Sea” was not the first science fiction in BEST AMERICAN SHORT STORIES.

Judith Merril’s “Dead Center” (F&SF, November 1954) made the cut five years earlier. And that may not be the earliest one, either. I once scoured the index and found another mid-50s pulp SF story, but I’ve forgotten what it was and I don’t feel like doing the search again.

Ted Sturgeon said he was the man being described in his story “…and now the news.”

Kind of irks me that Ray Palmer has had two biographies about him and his work, and Sturgeon has none.

About a decade ago I wrote a 30,000 word biographical/critical essay about Ted Sturgeon, written with one of Bruce Gillespie’s blockbuster fanzines in mind.

http://efanzines.com/SFC/SteamEngineTime/SET13.pdf

Sturgeon stated in Argyll that he lost his virginity as teenager to his secretly gay doctor’s boyfriend when he was briefly left in the doctor’s care while Sturgeon’s family was elsewhere. Something I didn’t include because it was the very vaguest of rumours was that Sturgeon may have been a male prostitute at some point. On at least one occasion the rumour was so garbled I wondered if it wasn’t an overwhelming misunderstanding and misremembering of the above. Certainly Sturgeon was very keen on Kinsey’s revelations about the prevalences of gradations of bisexuality.

@Piet Nel — I always understood that Merril’s “Dead Center” and Sturgeon’s “The Man Who Lost the Sea” were the only genre-originated SF stories to appear in Martha Foley’s Best series. (Much later, Harlan Ellison and Tim Pratt, at least, and I think others maybe, appeared in the series.)

George P. Elliott had several stories in Foley’s anthologies, and some of them, including I think “The NRACP”, were reprinted in F&SF. Could that be what you’re thinking of? Or something similar?

Thomas Disch, in The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of, wrote about being propositioned by Sturgeon and his wife at some point… and then proceeded to say absolutely nothing about Sturgeon’s writing. That was my first big clue (though hardly the only one) that that wasn’t going to be the kind of book I had hoped.

Chip Delany wrote in his FB page that Sturgeon hit on him. There must be a lot of stories not generally known.

The 1964 story in The Realist, “Encounter with the Beast” is more of a columnist’s satirical exposition:

http://www.ep.tc/realist/50/22.html

Sturgeon’s other 1964 piece in The Realist is more of a political op-ed

http://www.ep.tc/realist/53/10.html

Every now and then, I prod people to read Sturgeon’s “Mr. Costello, Hero”– it’s the one about a man who creates divisions among people. He gets some fraction of what he deserves.

It was written when Sturgeon was distracted by Joe McCarthy, and it keeps getting more relevant.

Unfortunately, the original text isn’t easy to find online, and the audio version is considerably different.

Page by page through the magazine version

Inconveniently formatted text. Skip down to Cost ell o

My only disagreement with Vonnegut and “Kilgore Trout” is that Kilgore Trout was an abysmal pornographer and hack, which Sturgeon never was. Vonnegut is closer to being Kilgore Trout than anyone else.