By Carl Slaughter:

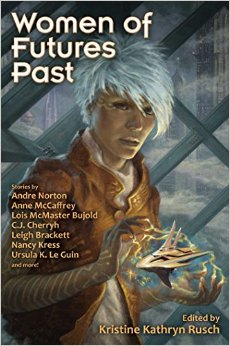

WOMEN OF FUTURE PAST

Editor: Kristine Kathryn Rusch

Released: September 6

Baen

Meet the Women of Futures Past: from Grand Master Andre Norton and the beloved Anne McCaffrey to some of the most popular SF writers today, such as Lois McMaster Bujold and CJ Cherryh. The most influential writers of multiple generations are found in these pages, delivering lost classics and foundational touchstones that shaped the field.

You’ll find Northwest Smith, C.L. Moore’s famous smuggler who predates (and maybe inspired) Han Solo by four decades. Read Leigh Brackett’s fiction and see why George Lucas chose her to write The Empire Strikes Back. Adventure tales, post-apocalyptic visions, space opera, aliens-among-us, time travel—these women have delivered all this and more, some of the best science fiction ever written!

Includes stories by Leigh Brackett, Lois McMaster Bujold, Pat Cadigan, CJ Cherryh, Zenna Henderson, Nancy Kress, Ursula K. Le Guin, Anne McCaffrey, C.L. Moore, Andre Norton, James Tiptree, Jr., and Connie Willis.

Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: Invisible Women by Kristine Kathryn Rusch

- The Indelible Kind by Zenna Henderson

- The Smallest Dragonboy by Anne McCaffrey

- Out of All Them Bright Stars by Nancy Kress

- Angel by Pat Cadigan

- Cassandra by C.J. Cherryh

- Shambleau by C.L. Moore

- The Last Days of Shandakor by Leigh Brackett

- All Cats Are Gray by Andre Norton

- Aftermaths by Lois McMaster Bujold

- The Last Flight of Doctor Ain by James Tiptree, Jr.

- Sur by Ursula K. Le Guin

- Fire Watch by Connie Willis

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Bill, is the data set also too small to support the argument that women were NOT discriminated against? I believe that was the idea Jayn and others were raising, so perhaps you are agreeing with them?

You can study history and draw conclusions when the data you have are sufficient to support (or detract from) those conclusions.

Fortunately, the counting done by Davin isn’t the only information we have to go upon. All of the material that Davin dismisses in his glide to his conclusions constitute material upon which we can rely to draw conclusions. If the numerical data is insufficient to conclude women were discriminated against, it is also insufficient to conclude that they were not. The obvious thing to do in that case is to look to the accounts written by people of the era that Davin tries to hand-wave away – almost all of which point towards the conclusion that women were discriminated against.

Soooo…. drop Fire Watch? It’s not as if it needs the signal boosting.

Davin’s research has always trotted out by certain parties to explain that there was never any discrimination in the field, but then his numbers don’t actually say that, and his conclusions are iffy, at best. Anyone with access to Contento’s Science Fiction, Fantasy, & Weird Fiction Magazine Index (cd or digital) can work out the publication gender breakdowns for themselves, and they don’t really match up with his. Take any sample set at random, say, Weird Tales, for 1940, and you get 12%, for example. (Earlier years are exceedingly worse. Far far worse.) But putting that to the side: it also ignores that under Dorothy McIlwraith’s editorial reins, things improved dramatically. In 1949, it was 22%! Which is suggestive. You do have to break out each editorial time period, and compare them against each other, and that might outline additional issues or interpretations of the data. But the data is there, in any case.

@ JJ: KBK is offering what I call a “Reader’s Digest argument”, after an article I read there sometime in the 90s which claimed that nobody should be complaining of being poor because [comparison of wages and salaries for various positions in the 60s vs. the 90s] the average person made 3 or 4 times as much now as they did then! What was omitted? The cost of living change between the 60s and the 90s, which went up significantly more than the wages and salaries did.

@ Bill: Now you’re getting into the chicken-and-egg argument, which is much beloved by apologists of many stripes. “How can you claim that X are being discriminated against if X don’t submit / apply for / participate?” This is where perception and representation make a difference. if X don’t see themselves being represented, they are going to be less likely to make the effort in the first place. In this particular instance, that means it’s the job of the editor (the person in the power position) first to put the word out that they are actively seeking more submissions from X, and then to follow through without falling into the related trap of judging the submissions from X against a set of standards already slanted to favor not-X. (AKA “I judge stories on merit, it’s only coincidence that my entire Best-Of list is stories by white men!”)

@Mark

So, you’re happy to draw conclusions from limited data in other circumstances,

What in the world did I say that leads you to that conclusion?

I think the bar you’re setting is too high,

I think you are wanting to argue about something, but I’m not sure what.

@BigelowT

is the data set also too small to support the argument that women were NOT discriminated against?

If, by “data set”, you mean the statement that SF mags between 1926 and 1965 had 1055 stories published by (at least) 233 women authors, then yes. To know if discrimination occurred, you need to be able to compare how stories submitted by women were treated compared to how stories submitted by men were treated. The “data set” is but one small insufficient part of that data.

I believe that was the idea Jayn and others were raising, so perhaps you are agreeing with them?

I refer you to my statement here, where I specifically said “And, just to be clear, I am not saying that women weren’t discriminated against” in attempts to ward off the possibility that I was sympathetic to any idea that women weren’t discriminated against. (In fact, I don’t see how I could have been more clear – perhaps you could propose a better wording?)

@Lee – If I came across as an apologist by bringing up the idea that society broadly suppressed women such that they were reluctant to write SF stories, that was not my intention. Certainly, Campbell and the other editors could have made greater outreach efforts.

Jayn, are you aware I am devoting one review a week for a year plus to Tanith Lee?

@Bill

Maybe I misread you then. I’ll start again.

You are giving the appearance to me of wanting a high level of data in a subject where that data inevitably doesn’t exist and basically has no chance of existing. One of the reasons it doesn’t exist is that e.g. Campbell didn’t think the level of female representation was a problem and so didn’t record the data on his slush pile that you want.

When the problem is under representation or lack of concern about a subject, it’s inevitably more difficult to prove it because the neglect itself means the data isn’t recorded.

So we have to go to secondary comparisons of data (such as proportions of stories published vs gender breakdown of the population) and more qualitative evidence such as the known attitudes others have posted about.

Put it another way: if it’s accepted that gender attitudes in the period in question were poor, is it reasonable to say that the problems all happened prior to reaching the slushpile unless it can be conclusively proved otherwise?

@JDN’s fine list: Though I appreciate Élisabeth Vonarburg, Reluctant Voyagers is a curate’s egg. It has some very remarkable imaginative and observational passages (love the scene where the main character and a child play with ants in a garden and discuss weighty philosophical and moral issues) but it is long and repetitve, and Vonarburg‘s racism, only sporadically obvious in her other works, pervasively affects her vision of an alternate modern Montréal. I would suggest short stories, maybe “Stay Thy Flight” or “The House Beside the Sea.”

James Davis Nicoll:

I really appreciate your review of Davin’s work. I have a question, though: what was the erasure Pohl did of his wives?

It has been a while since I read the work and I do not own it but my memory is Pohl neglected to mention them in a context where it would have been logical to mention them as writers.

I preferred Larbalestier’s The Battle of the Sexes in Science Fiction.

@James Davis Nicoll

Well, you have actually read and reviewed Partners in Wonder, so you can criticise Davin on the basis of the book itself.

Justine Larbalastier’s The Battle of the Sexes in Science Fiction is indeed excellent, as is Lisa Yaszek’s Galactic Suburbia.

The Secret Feminist Cabal: A Cultural History of Science Fiction Feminisms by Helen Merrick is another academic study in a similar vein that I haven’t yet read, because of the hefty price tag. Though the price seems to have come down by now, hurray.

Finally, filer Robin Anne Reid has edited two volumes of Women in Science Fiction and Fantasy. Again, I haven’t read it because of a combination of hefty price tag and a limited university library.

@James: those are EXCELLENT suggestions. Some I’ve read, some I own, and they’re all worthy, so I’m going to believe that the others are equally interesting.

Rusch shouldn’t have gone on about Clingerman so much and not put one of her stories in there! She’s legit past and forgotten (Connie, Ursula, Lois, Anne — not so much) and should have been in there. Does anyone have a link to some of her work? Subversive or housewives in space, whatever.

Clingerman and some of the ladies on James’ list could have gone in in place of “Fire Watch”. And why not one of Connie’s short stories if she had to be in there? “Letter From the Clearys” is early and devastating; so’s “Last of the Winnebagos”. I’d have liked a Killough tale, myself. Vinge! Van Scyoc!

What BigelowT said; those statistics cited by KKR are useless to either prove or disprove discrimination. What I am objecting to is KKR’s apparent effort to use those statistics as part of her case to deny the existence of discrimination.

What the numbers KKR cited can prove is this, and only this: some women were writing SF between 1926 and 1965. Whether those women were writing SF among SF writers in any percentage close to the 50% of the population they demographically represent, or whether they were were something like a 1% drop in the bucket, we don’t know. If it were close to 50%, or even 40 or 30% – well, it wouldn’t be proof of nondiscrimination in the SF field, but it would be evidence in its favor, IMO. If it were 1% or thereabouts? Not proof of discrimination – but evidence. But KKR does not provide those percentages.

Which would be fine if the only aim KKR had with her anthology was to prove to ignorant young folks (apparently mostly women, in KKR’s view) that, yes, there really were women who wrote SFF between 1926 and 1965 – good SFF, too. I find it hard to believe that there are too many young women who think that absolutely NO women ever wrote SF in the past (except KKR, apparently, since they were talking to her and according to KKR they did evince some awareness that she was an SF writer). But the well of human ignorance is bottomless and I’m fully prepared to believe in the existence of such hypothetical dunces. If KKR’s mission statement was solely to educate these poor benighted souls, as well as the undoubtedly much larger proportion of the young who are aware that women DID write SF but no longer have the information to know about the great foremothers of the field, I don’t think I or anyone else would have a problem with that.

What sticks in my craw and raises my hackles and does other things to portions of anatomy I probably don’t possess is (as I said) her statement that “The idea that women are discriminated against in science fiction is ludicrous to me.” Also her statement that “I was coming to realize that today’s young female writers had no idea that they weren’t storming the barricades – that there were no barricades and had never been any in SF -” (my bolding).

Seriously? She knows for a fact that since 1926 there has been no discrimination? What she writes there is contradicted even within her own preface and story introductions. Later in her book, in her introduction to Andre Norton’s story, KKR briefly mentions that she changed her name legally from Alice to Andre mainly because “she wanted to write boys adventure fiction, and in 1934, she believed it would be easier to sell to that market if she had a male name. She did not become a science fiction writer for nearly twenty years after the 1934 publication of her first novel.”

Sooo – by 1953 or so there was for sure no discrimination problem in SF, so Andre Norton just continued to use the name out of unnecessary habit? Citation needed. Checking Wikipedia, I find Andre Norton’s first SF publication happened in 1947 – The People of the Crater. Now Wikipedia is not that reliable, but Google Books seems to back it up completely – including the fact that Norton published it under the male pseudonym Andrew North. Apparently Norton was still concerned that a male pseudonym was necessary – even for the SF field. Would KKR say that Norton’s concerns were “ludicrous”?

KKR even describes the process in her preface, noting that Damon Knight published an anthology of SF of the Thirties without one woman, that Greenberg and Olander had two women out of 21 in their anthology of the Fifties, that Silverberg had one of 18 in his anthology for the same decade, that Malzberg and Pronzini had 0 out of ten for theirs. She mentions that even a best-of collection from 1993 had only 7 out of 23 women, and among those only one of the 2 female Hugo winners for that year.

She goes on to say, “Discrimination? Oh, probably not. Probably something called unconscious bias or second-generation discrimination. The person who has unconscious bias, unlike a hardcore bigot, will prefer someone who looks like them to someone who doesn’t.”

Er… how does KKR square this with her blithe pronunciation that the very concept of discrimination in SF is ‘ludicrous’? Regardless of whether the discrimination is motivated by conscious mustache-twirling bigotry, subconscious patronizing and dismissal or unconscious bias, the end result to the aspiring female writer still means being often discarded from the slush pile, being forgotten from the anthology, eventually falling out of print.

It’s okay to say that a large proportion of your potential readers hold a belief that you think is wrong, if you’ve got the data to back it up and a convincing way of presenting it. To say that the belief of a large proportion of your potential readers is ludicrous is, IMO, gratuitously insulting. Even being insulting is not entirely out of bounds – but you’d BETTER have the data and be absolutely convincing with it to justify the insult. KKR, IMO, does not.

She may have some doublethink going on regarding discrimination, as when she says, regarding the reasons for the best stories being forgotten, “The young writers, particularly female writers, immediately assumed discrimination. Since I know most of the editors and publishers in the science fiction field, I never assumed discrimination.” (Did she know their unconsciousnesses as well as their consciousnesses?)

Or maybe she’s aware that proclaiming that it’s ludicrous to believe that there could possibly be or ever have been discrimination in SF is insulting and likely to outrage, and she’s less interested in soberly substantiating a controversial claim than in generating publicity for clicks and giggles. Whether that’s what she’s doing or not, it might actually increase sales. I suspect that any lost sales that my review (for example) might cause would be more than offset in some circles by the word that some horrid SJW gave KKR’s book a bad review. I’d rather not believe that’s what KKR is doing, though.

@JDN

YES! And I am happily following along.

@lurkertype

I checked sketchily, I didn’t find a single thing of Clingerman’s online.

Looking through my collection for other recs, I refound my copy of The Hidden Side of the Moon, collection of short stories by Joanna Russ, and was happily reminded of just how good a fiction writer she really was. Funny that KKR only mentions her to dismiss her opinion on home-and-hearth writers, because when I check her on Amazon I find she seems to meet the criteria KKR sets for worthy woman writers being unfairly forgotten; her short works were nominated for Nebulas several times and won twice, and one even won a Hugo as recently as 1982, but now all her short fiction seems to be out of print. It’s probably too much to ask that KKR consider “The Cliches From Outer Space” as a candidate, but “The Experimenter” is suitably memorable and chilling, and has the male protagonist KKR prefers. She meets the criteria for a forgotten writer better than a lot of the writers KKR chose, IMO, so why the omission? Unconscious bias?

I never assume anyone reads my reviews 🙂

Something went wrong with Lee’s North American career around 1990, maybe? She kept being published in the UK (she’s one of the women Gollancz deigns to admit wrote SF) but for some reason US publishers stopped picking up her stuff.

She may have been victim of having a book marketed as horror just as the horror market imploded. The timing looked right to me, anyway.

@Mark

You are giving the appearance to me of wanting a high level of data in a subject where that data inevitably doesn’t exist and basically has no chance of existing.

It’s not so much me wanting the data, as it is the necessity for the data to exist in order to prove the discrimination that several (most?) people here believe happened. We can infer discrimination in SF from other directions, but we can’t prove it. If someone is invested in the idea that SF editors/publishers were discriminating against women (again, a premise that I am not going to dispute here), it’s unfortunate for them that the data doesn’t exist.

Jayn alluded to some sort of demographic proportionality as being evidence for or against discrimination. I don’t think that is a particularly useful yardstick, because during the period under discussion, women were far less interested in SF than men (I believe that to be the case even today, just not so much). If 12% of the stories in Weird Tales in 1940 were written by women, but women were only 12% as interested in writing weird fiction as men were, and submitted only 12% of the stories in the WT slushpile, then it is very difficult to attribute any of the imbalance to discrimination by the editors/publishers of WT. OTOH, if you could show that women were in fact 20% as interested, the case becomes somewhat stronger. But again, the data doesn’t exist.

If KKR had started with the premise “I’ve run into women who are unaware that SF has a rich history of women writers, and this book is meant to expose modern readers to that legacy,” and went on to say “Good stories can always find a market, even if they were written by women in an era when society did not look to them for genre literature” I think she would have just as useful a book and would be on much stronger ground logically. But this business of using a very sparse data set to prove or disprove discrimination is chasing windmills.

(And I think some of this discussion results from applying 21st century standards to people who lived and worked 50 – 90 years ago, which isn’t particularly useful or illuminating. I don’t think JWC was a bad person because he didn’t devote his editorial efforts to making sure that half of all Astounding bylines were feminine.)

Bill: It’s not so much me wanting the data, as it is the necessity for the data to exist in order to prove the discrimination that several (most?) people here believe happened.

That’s not really what’s happening here. What’s happening here is that KKR and ELD are claiming that discrimination against women in SF did not exist, without any real, legitimate data to support that — and people here are not only 1) pointing out that those claims have not been proven by KKR and ELD, people here are saying that 2) if anecdata is to be considered substantiation, then there is a hell of a lot more anecdata that says that discrimination did (and still does) exist, rather than indicating that it doesn’t.

@JJ

Exactly. And…

Some significant anecdata in favor of the possibility of discrimination was even apportioned by KKR herself in the book, as I mentioned above (reporting that no woman’s story was published in anthology of the 30’s sf, not even C. L. Moore’s landmark “Shambleau”, women showing up in token numbers or none in other historical and even near-contemporary SF anthologies), but she handwaves this off as “Probably something called unconscious bias or second-generation discrimination” which apparently doesn’t count as real discrimination – thinking so would be ludicrous! (sorry, that still annoys me).

Bill,

I should very much like to know where you got your figures for this assertion. I’ve been told all my life that “women don’t like science fiction”. Often to my face, while I have an actual SF book in my actual hand. And never with any supporting evidence. It seems to be one of those things that “everybody knows”… and you know how unreliable that sort of thing can be.

I’m sorry if I sound testy, but as a women with a substantial SF library, with plenty of female SF-fan friends and acquaintances, I’m honestly getting a little tired of hearing “girls don’t read SF” without substantiation.

@James Davis Nicholl:

As to Tanith Lee’s career in the US, it’s been many years, but I recall Lee saying something in an interview in Locus about her career in the US. If I remember rightly, she mentioned taking an offer from a publisher other than DAW, for more money and HC publication, because at the time, DAW wasn’t doing HCs and she went for the opportunity to be published in HC. Somewhere around that point, her career in the US stalled. C.J. Cherryh was the first author done in HC by DAW, as I recall. Don’t bet the farm on the accuracy of my memory. 😉

No love for Doris Piserchia yet? The Spaceling was my introduction to her, and probably still my favorite of her books, but if you don’t like YA vibes, then maybe try A Billion Days of Earth.

She also wrote short fiction, about which I know zilch other than she had a story in The Last Dangerous Visions.

@ Cassy —

Note that I didn’t say “women don’t like science fiction” or “girls don’t read SF”. Obviously, neither statement is true.

A specific counter-example, like yourself, doesn’t disprove the general statement (and I could provide many more counter-examples; one of my best friends met her husband through SF, and I know a number of other women who are deeply interested in SF/F).

But as far as figures — Everything I can count regarding gender balances in SF/F from 1926 – 1965 leads me to believe that my statement is correct. Look at authors in the magazines. Look at names that pop up in fanzines. Look at photos of attendees at club meetings. Look at Letters of Comment in magazines. Look at membership rosters of conventions.

Historically, there have always been women involved in fandom. Historically, there always have been more (sometimes, many more) men involved. Some of that imbalance may be (is?) due to discrimination. But some of it roots from the fact that men (in general) are wired differently than women (in general), and this difference manifests itself in levels of involvement in fannish activities.

Bill said:

Whoooooooa nope. The march of science has lately obliterated every claim that the genders are “wired differently”; differences previously considered inherent have been variously traced to cognitive biases, culture, social pressure, and, yes, discrimination.

(For some of the particularly interesting studies, look up “stereotype threat”.)

headdesk

Bill, you are totally ignoring the reasons that photos, fanzines and convention rosters had a lot fewer women in them, that had nothing to do with the way women are “wired”.

What’s more, the way women were the driving force behind Star Trek fandom makes it clear that they are indeed “wired” that way — and it just takes an environment where they aren’t being excluded for that to become apparent. Which usually ends up being an environment women have made for themselves, because so many men have worked so hard to keep women out of their “manly, wired-differently” environments.

And honestly, I am so tired of hearing that “women and men are wired differently” bullshit. I’ve been listening to men say that my entire life as a way of justifying discrimination and exclusion against women. It’s not true, and it reflects very badly on you that you keep repeating it as if it’s true. 😐

It brings to mind the cartoon of the dinosaur watching the meteor streaking across the sky and saying, “hey, what’s that?”.

Everything I can count regarding gender balances in SF/F from 1926 – 1965 leads me to believe that my statement is correct. Look at authors in the magazines. Look at names that pop up in fanzines. Look at photos of attendees at club meetings. Look at Letters of Comment in magazines. Look at membership rosters of conventions.

Everything you bring up here is prima facie evidence of pervasive discrimination in the fannish genre world.

So we’ll ignore the women-heavy categories of fannish activities like costuming and fanfiction, go back to the old claim women are just more nurturing and less scientific, and call it a day?

Nope. not satisfied. We have had decades of discussion of the difference between men and women, how much is socialized from nursery onwards, and how there’s a vastly smaller difference between the average man and average woman than the people who use it to explain the social gaps are willing to admit. Your vast oversimplification is even more self-serving than are those from the women trying to point out the discrimination.

Bill,

Everything I can count regarding gender balances in SF/F from 1926 – 1965 leads me to believe that my statement is correct. Look at authors in the magazines. Look at names that pop up in fanzines. Look at photos of attendees at club meetings. Look at Letters of Comment in magazines. Look at membership rosters of conventions.

Look at the way that pervasive sexual discrimination kept women out of magazines, fanzines, and clubs. Look at the way sexual harassment kept women away from conventions. (You don’t think there was a pervasive “boys club/no girlz allowed” atmosphere at conventions? Trust me; I was going to SF conventions in the 1970s and I can tell you differently.)

What you’re describing is symptomatic of pervasive discrimination. Look at the way the gender balance at conventions has moved toward parity in the last decade or two, and the “sudden” success of female SF authors (Nebula awards! Hugo awards!) and ask yourself if human brains have been rewired in the space of a decade… or if pervasive barriers to female participation have started coming down. Occam’s Razor….

@Bill

Possibly Cassy B. was making a general point about the potential irritation factor of someone making a sweeping statement of some controversy as if it were an established fact when there’s no convincing proof. Like, saying “the fact that men (in general) are wired differently than women (in general) and this difference manifests itself in levels of involvement in fannish activities.” (Did women get rewired in the 60’s when Star Trek came out?) Or, “It’s ludicrous to say there’s any discrimination in science fiction!” (Sorry, I just can’t get over that). I suppose you’re ahead of KKR on points for not saying Cassy B is being ludicrous, as well as not publishing a book using wonderful stories as an pretext to rant about it while attaching unnecessary statistics that don’t actually support your rant.

On that note, I looked through the book again (yes, I am getting obsessed, for some it’s the moon landing ‘hoax’, for me it’s this book). I was wondering about this line:

“Articles on discrimination against women in SF consistently cite Catherine Lucille Moore’s 1933 decision to use her initials as a byline as proof that she was afraid she would be discriminated against for her gender. Nothing could be further from the truth.”

KKR makes such a flat proclamation, but she then paraphrases some source that says C. L. Moore said she only used initials to keep her employer from finding out about her writing for the pulps, NOT for any other reason (like to conceal her gender). KKR, however, does NOT quote C. L. Moore saying this. I wondered why, wondered if what C. L. Moore said might be open to interpretation. KKR gives her source as Davin, P. 114, which – huzzah! – turned out to be free on Google Books.

“Why did C. L. Moore use initials? Most knowledgeable fans have known the true reason for many years. Far from any desire to conceal her gender from the fantasy and science fiction world where absolutely no one cared [my bold], the reason was purely mundane; to protect her job. Moore worked at a bank, said Marion Zimmer Bradley, and “C. L. Moore told me once that she had adopted initials because had she published her first story…under her own name, she might have lost her job as a bank teller. In 1933, the depths of the Depression, Ms. Moore was the only working member of her family and the sole support of her aging parents; she did not want to risk her livelihood on the uncertain business of fiction writing.”

That’s all? So we have MZB’s memory of a reason Moore gave for using initials that does not include either an avowal that it was her only reason or a denial that gender was a factor. I attempted to find the source for MZB’s quote, but it was inaccesible online. Stymied, I found myself gazing at the statistician’s bold statement that in the SFF world of 1933, absolutely no one cared about C. L. Moore’s gender. I wondered helplessly what numbers he could be privy to that he could so confidently claim that in the world of 1933 SFF not one single person cared that C. L. Moore was female. Drawn on irresistibly, I fell into the vortex of mystery…

(to be continued)

@Cassy B

I posted that reply to Bill above before I saw yours, I didn’t mean to speak for you.

Back to the vortex…

Jayn, you have it exactly. I’m tired of sweeping statements that “women were far less interested in SF than men” — especially when the reason given is handwaving like “brain wiring” with no actual valid study to back it up. Would it be equally valid to say that African-Americans were “far less interested in SF” than European-Americans? After all, looking at convention photos, publication records, etc, hardly any African-American are represented historically in SF fandom, and even today they are strongly under-represented; even more under-represented than women are. Would Bill therefore conclude it must be brain wiring or some other fundamental difference between African-Americans and European Americans? I certainly hope and expect that he would not. But that’s the level of support he has for his argument about women in SF.

And I really am sorry for snapping at Bill, but it’s just the last of a lifetime of “boys club” reasoning and I, well, snapped. <wry>

<edit to add> Jayn, I saw your apology. Accepted, but unnecessary; you understood my meaning perfectly and made my point in a different way than I did. Sometimes it takes a different approach to get through. It’s all good.

I entered the conversation only to make the point that a count of # of women authors and stories in a given period was not enough data to say that women were, or were not, discriminated against in that period. I haven’t seen anything here that refutes that observation, and some seem to agree with it, so that is good.

I’ve rejected several times the argument that women weren’t discriminated against; I’ve said here

https://file770.com/?p=30835&cpage=1#comment-485753

that social factors matter, and that they are a subtle form of discrimination. I’ll even say that yes, women were and are discriminated against in SF. We agree on that.

But I won’t concede that all imbalances are solely due to discrimination – overt and specific, or general cultural pressures. To say that imbalances in photos, rosters, bibliographies, etc. is prima facie evidence of discrimination is the same chicken and egg argument that Lee brought up earlier. You can’t anymore justify the statement that the underrepresentation of women in SF is clear proof of discrimination and only discrimination any more than KKR can use the existence of some stories as proof that discrimination was nonexistent. It’s not 100%, it’s not 0% — it’s somewhere in between, and likely has been dropping from 1926 until now.

It’s been said many times on comments here that gender parity in publication of stories is a good thing, because women have a different voice and POV. I don’t think you can reconcile that belief with the idea that men and women aren’t wired differently.

@Cassy — you reject my statement that “women were far less interested in SF than men”. Do you believe the contra — that women were just as interested in SF as men? Is there any data that supports such a view?

Bill: you reject my statement that “women were far less interested in SF than men”. Do you believe the contra — that women were just as interested in SF as men? Is there any data that supports such a view?

Is there any “data” which contradicts such a view? “Data” that cannot be explained by alternate forms of “data”?

Bill, by the same evidence you give regarding women, African-Americans were, and are, far less interested in SF than white Americans. Do you accept this contention? Why or why not?

You made a statement of fact. I’m asking for support for that statement. So far I haven’t seen support for it. An assertion is not evidence.

Women may, or may not, have been as interested in SF as men. As it was your assertion that they were not, the burden of proof is on you.

Bill said:

Sure you can, at least as long as you also think that voice and POV can be affected by life experiences. If women are systematically treated differently than men, voilà!

WTF.

Women aren’t wired differently, Bill.

Women are socialized differently by our culture. It’s something that is essentially forcibly done to them, as a result of the way women are treated from the moment they’re born. They are constantly treated like sex objects. They are constantly told that they are supposed to be the nurturing ones. They are constantly told that they aren’t as smart, or as mentally or physically capable, as men.

As Petréa has says, of course women often come to think differently because of that — and as she has also pointed out, claims that women are biologically “wired” differently have been consistently discredited in medical reasearch.

Given that you apparently don’t have any understanding of Biology, Sociology or Psychology, you would be well-advised to not display it so prominently on here, because such ignorance seriously undermines the credibility of anything you say.

I just can’t even. I mean, I know that there are some men still living who spout this sort of bullshit. I just didn’t expect to see it on File770. 😐

People are wired differently.

Chromosome structure isn’t necessarily a factor in that. I know at least a dozen people who can do higher math problems practically in their sleep who can’t balance their checkbooks, for example. There are both men and women in that group. People all have different skill sets which aren’t coded pink or blue.

I’m kind of impressed with how quick evolution works. Just 1-2 generations has caused so much difference in the female biology that a lot more women are winning awards.

Hampus Eckerman: A lot of the voters have turned female, too.

That “women just aren’t interested in SF” and “women just aren’t writing and submitting SF” argument has been trotted out since forever. Ditto for that “women are wired differently” crap.

However, it’s not true. Women (and POC) have always been reading SF. In The Battle of the Sexes in Science Fiction, Justine Larbalastier quotes lots of letters from letter columns from SF magazines of the 20s and 30s. Quite a few of these letters are from female fans, several of them mention that they know several other women who read SF. Some of those letters are online at Justine Larbalastier’s site. Coincidentally, some of the letters by young male fans (one of them a teenaged Isaac Asimov) might explain why not more women engaged with fandom, since it was clearly a hostile space to women even back then.

I guess a lot of the women here have heard the “women and girls just aren’t into SF” stereotypes and the “women are wired differently” claims so many times (and probably had people telling us to our faces that we’re wrong when we say that yes, we like SF and no, we’re not nurturing and no, we don’t like insert stereotypically feminine thing here) that we’re heartily sick of it, which is why Bill is getting so much backlash.

What is more, these stereotypes often hinder girls from developing an interest in SF. I was born in the 1970s and had liberal parents. However, no matter how many longing looks I cast at Star Wars toys, I was never given any. No matter how many times I remarked “This looks like an interesting movie”, whenever there was a trailer for an SF film on TV or a poster at a bus stop, I only got taken to Disney movies. I was given a lot of books, but never SF books, just girls at boarding schools or girl detectives or teen romances (Monica Hughes snuck in there somewhere, probably picked up because someone thought it was about ancient Egypt). The first SF novels I bought for myself were hidden at the bottom of a closet, where no one would find them (when I cleared out my room years later, I found a half-read SF novel from the 1980s in said closet – I tried to read the rest, but unfortunately the suck fairy had visited). When I drew up a list of books I wanted for my 15th birthday (because otherwise I would only get more teen romances and boarding schools and problem novels), my aunt doublechecked with me whether I really wanted a particular book (an Anne McCaffrey novel), because it was science fiction and girls don’t read that.

Girls and women are bombarded with these messages all the time, so it’s no wonder that “women aren’t interested in science fiction” becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Steve Carper (who thinks more highly of Davin’s book than James does, but still finds it badly wanting) estimates that in 1926-1949 period, women wrote about 3% of the stories published in sf magazines. He also notes that few of them stayed in the field for long, based on Davin’s counts:

(Quote and stat are from an article Carper wrote for NYRSF, available here.

I’m reminded about how all those orchestras who didn’t hire women as performers because women just objectively weren’t as good as men were at playing whatever musical instrument suddenly started hiring women when they were basically dared to start auditioning musicians behind a screen, so the people who would be hiring them couldn’t tell who were men or women. Suddenly the very same objective judges who objectively knew that men were better performers than women found themselves hiring as many women as men.

But they would have sincerely told you that they were truly objectively just judging skill when they hired a vastly larger proportion of men to women, before the blind auditions became a thing.

People can sincerely, honestly, believe themselves to be objective when they’re not. And funnily enough, in the 1930s and 40s and 50s and so on, editors weren’t “blind auditioning” writers. They usually knew the sex of the writer. And everyone knew that women didn’t read or write SF. Men did. You know, men like the ineluctably masculine Tiptree.

If we were looking at orchestral musician proportions from, say, the 30s or 40s or 50s, we might assume that women were hardly ever musicians; that even when they were, they probably didn’t audition much, and that even when they did, they just weren’t as good as the men. But now, thanks to blind auditions, we know that women really ARE just as good musicians as men are.

Unconscious bias. It’s a thing. Were (and are) editors less prone to it than orchestras, do you think?

Cora: You’re too polite. “Bill is getting so much backlash” because he’s talking bollocks (pun unintended, but appropriate).

Unconscious bias is still discrimination. And there was plenty of conscious bias going on back in the day too.

Anyway, the vortex thing, barely escaped with my life. Ahem.

Helplessly, I say, my eye was drawn to these words of Davin’s in Partners in Wonder, which came after much verbiage apparently intended to prove that all SFF fans and professionals knew C. L. Moore was a woman pretty much immediately at the start of her career and none had a problem with it:

“Obviously, it was quickly and widely known in the fantasy and science fiction communities that the popular “C. L. Moore” was a woman – and it mattered not in the least.”

Er…bullshit? A widely known story about Moore is that she met her husband Hank Kuttner when, as an established SF writer in his own right, thus presumably a knowledgeable member of the SFF community, he wrote a fan letter to Mr. C. L. Moore – in 1936. That is, three years after her landmark tale “Shambleau” was published to acclaim, followed by “Black Thirst”, “The Bright Illusion”, and “Black God’s Kiss” (the debut of Jirel of Joiry, the prototype Warrior Princess) all of which were highly praised and good enough to end up in the “Best of C.L. Moore” volume I have on my lap. Even after the renown of these great stories, a prominent member of the SFF community did NOT know that the talented C.L. Moore was a woman, AND assumed that the gender-neutral name of course belonged to a man.

The story of how Moore and Kuttner met is well known to anyone with any significant knowledge of Moore. It is no recent SJW fabrication; a token search on Google Books shows it goes back to at least 1962 (in Amazing Stories). Since I can’t imagine a man so obviously versed in SFF as Davin is NOT aware of it, I assume he deliberately omitted it because it undermines his preferred sweeping conclusion…a depressingly familiar tactic.

Shaken, I search for more on Moore, and find an explanation why she and other writers ONLY adopted male pseudonyms, as well as a denunciation by Davin on the ridiculous notion that any woman in SFF history ever used a male pseudonym to avoid discrimination. (P. 99)

“...it is impossible to find any evidence of the practice – anywhere. This widespread allegation is a complete fiction!” (His italics, my bold). He tells us that two whole men used female pseudonyms to publish SFF stories, therefore it’s ridiculous to suppose there could be any bias against women in SFF publishing. This drops from mere special pleading into the depths of the sublimely goofy with this explanation of Moore and other women’s male pseudonyms:

“…none were deliberate attempts to conceal gender identities from the science fiction community…this happened because wives collaborated with their husbands – and the resulting co-authored stories by spouses appeared under a single male pseudonym.”

Why of course! That’s the only explanation! When a man and woman get married they become one flesh, and that flesh must naturally display ONLY a penis, never the least public hint of a possible vagina! What could that possibly have to do with gender discrimination, concealment or sexism?

What was Davin’s basis for his sweeping declaration that it is impossible to find evidence anywhere of a woman using a male pseudonym in SFF? His survey of 288 stories published between 1926-1949. When I read those dates I started to twitch. What about Andre Norton? Who has said she took a male pseudonym to avoid discrimination? Who published her first short work of SFF in 1947 under the pseudonym Andrew North?! I had thought Davin heroic for risking lumbago and postnasal drip in counting stories through countless crumbling pulp magazines to gather a complete index of invaluable hard facts. Is he unreliable even in that?

I search for Norton in his book. I find this (page 154), in a chapter which begins by implying that Tiptree was unjustifiably paranoid for believing in the “myth” that she needed a male pseudonym to be taken seriously in SFF. He goes on, “Sheldon kept up this subterfuge till her gender was accidentally revealed in 1977. Given the number of women who were being nominated for and winning Hugos by that time, it is difficult to believe there was any real need for such secrecy. Indeed, Andre Norton, another woman who published under a male pen name, (which has also been frequently cited as another explicit example of discrimination), explicitly said as much. Speaking in the 1970s she stated that, while there might have been a need for male pseudonyms earlier in the field, “This is not true today, of course.”

My blood pressure rises. And because I have learned distrust, I grimly fetch Andre Norton’s complete quote from its source (More Women of Wonder, p. xxviii):

“When I entered the field I was writing for boys, and since women were not welcomed, I chose a pen name which could be either masculine or feminine. This is not true today, of course. But I still find vestiges of disparagement – mainly, oddly enough, among other writers. Most of them, however, do accept one on an equal basis. I find more prejudice against me as the writer of “young people’s” stories now than against the fact that I am a woman.”

So…Andre Norton was saying in the 1970’s, with an illustrious SFF career of 20 years standing, that she STILL saw “vestiges” of disparagement against her as a woman – just less than previously and less often than she was disparaged as a writer for children. And you, Professor Davin, saw that quote and deliberately cut that part out. And you did it so you could use the remnant to DARE try to throw shade at TIPTREE to imply that she was a deluded ninny for believing that there might be sexism in SFF. You motherfucker.

…I really have to stop this, I’ve sprained my chiasma with so much eye-rolling. I think I can safely say that Google Books is an invaluable tool for deciding not to buy a book after looking at a few pages (especially a book as thick with WTFuckery as Davin’s). Also that KKR’s praise of Davin as a source seems a tad…disproportionate.

Damn, correction of the first line in the 9th paragraph, should read:

What was Davin’s basis for his sweeping declaration that it is impossible to find evidence anywhere of a woman using a male pseudonym in SFF to escape sexism?

And sorry for babbling on so long.

Ursula K. Le Guin once recounted in an essay for The New Yorker an anecdote about submitting a short story to Playboy in the late sixties. Her agent, Virginia Kidd, had sent the story, “Nine Lives,” a work of science fiction in which most of the characters were men, to the magazine’s fiction editor. “When it was accepted,” Le Guin wrote of her agent, “she revealed the horrid truth.” The horrid truth, of course, was that the two initials at the front of her pen name, U. K. Le Guin, stood for Ursula Kroeber. The story’s author was a woman.

Playboy’s editors responded that they would still like to publish the story, but asked if they could print only Le Guin’s initials, lest their readers be frightened by a female byline. “Unwilling to terrify these vulnerable people,” Le Guin wrote, “I told Virginia to tell them sure, that’s fine.” After a couple of weeks, Playboy asked for an author bio. “At once, I saw the whole panorama of U.K.’s life,” Le Guin remembered, “as a gaucho in Patagonia, a stevedore in Marseilles, a safari leader in Kenya, a light-heavyweight prizefighter in Chicago, and the abbot of a Coptic monastery in Algeria.” Eventually, Le Guin did submit an author bio. It read: “It is commonly suspected that the writings of U. K. Le Guin are not actually written by U. K. Le Guin, but by another person of the same name.” Playboy printed it.

Ursula K. Le Guin on Writing in the 21st Century

Yep, in 1968, girl cooties were still a problem for male readers.

@Jayn: You’ve done a real woman’s job plowing through this mendacious crap. Please appertain yourself many drinks and I wish your eyeballs well. Thanks for doing better research than the “critic” did — even on his own stats, as the 3% figure shows.

Thank you, lurkertype, don’t mind if I do. Your appreciation means a lot, especially after the migraine I got wading through and debunking Davin’s stuff.

Have some more appreciation from me, Jayn.