(1) WHEN WILL YOU MAKE AN END? Unlike other recent kerfuffles, John Scalzi has a good deal to say about the copyright controversy in “Two Tweet Threads About Copyright” at Whatever.

Background: Writer Matthew Yglesias, who should have known better but I guess needed the clicks, offered up the opinion that the term of copyright should be shortened to 30 years (currently in the US it’s Life+70 years). This naturally outraged other writers, because copyrights let them make money. This caused a writer by the name of Tim Lee to wonder why people were annoyed by Yglesias’ thought exercise, since he thought 30 years was more than enough time for people to benefit from their books (NB: Lee has not written a book himself), and anyway, as he said in a follow up tweet: “Nobody writes a book so that the royalties will support them in retirement decades later. They’re mostly thinking about the money they’ll make in the next few years.”

This is where I come in….

6. The moral/ethical case is ironically the easiest to make: think of the public good! And indeed the public domain is a vital good, which should be celebrated and protected — no copyright should run forever. It should be tied to the benefit of the creator, then to the public.

7. Where you run into trouble is arguing to a creator that *their* copyright should be *less* than the term of their life (plus a little bit for family). It’s difficult enough to make money as a creator; arguing that tap should be stoppered in old age, is, well. *Unconvincing.*

8. Likewise, limiting that term limits a creator’s ability to earn from their work in less effable ways. If there’s a 30-year term of copyright and my work is at year 25, selling a movie/tv option is likely harder, not only because production takes a long time (trust me)…

9. …but also because after a certain point, it would make sense to just wait out the copyright and exclude the originator entirely. A too-short copyright term has an even *shorter* economic shelf-life than the term, basically. Why on earth would creators agree to that?

The comments at Whatever include this one by Kurt Busiek distinguishing patent and copyright protections:

“I’m not sure I understand why copyright and patent terms are such different lengths. My father is an electronic engineer who designed an extremely successful glassbreak sensor (e.g. for home security systems). Guess how long a patent term is at max? Twenty years from date of filing. It’s a far cry from 120 years or life+70 for copyright.”

Because patents and copyrights cover different kinds of things.

On the one hand, patents are often more crucial — if we had to wait 120 years for penicillin to go into the public domain, that hampers researchers and harms the public much more than if we had to wait that long for James Bond. The public domain needs that stuff sooner.

If you patent a process that allows solar radiation to be collected and stored by a chip, then anyone who wants to do that has to license the process from you, even if they came up with it independently. You’ve got a monopoly on the whole thing.But if you write a book about hobbits on a quest to dunk some dangerous mystic bling in lava, well, people can’t reprint your book or make a movie out of it without securing permission. But they can still write a book about halflings out to feed some dangerous mystic bling to the ice gnoles — what’s protected by copyright is that particular story, not the underlying plot structure. Tolkien gets a monopoly on his particular specific expression of those ideas, not on piece of science that can be used a zillion different ways.

I’m sure there are other reasons, but those two illustrate the basic idea, I hope.

(2) RIGHTS MAKE MIGHT. Elizabeth Bear’s contribution to the dialog about copyrights is pointing her Throwanotherbearinthecanoe newsletter audience at three installments of NPR’s Planet Money podcast that follows the process of gaining rights to a superhero. At the link you can hear the audio or read a transcript.

- Comic book companies horde thousands of characters for future use : Planet Money : NPR

- Thousands of superheroes exist in the public domain : Planet Money : NPR

- Micro-Face gets an original comic book : Planet Money : NPR

Here’s an excerpt from the third podcast:

…SMITH: The daughter of the original artist who created Micro-Face, Al Ulmer. Maybe we should have our lawyers here just in case it gets a little litigious. After the break.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC)

MALONE: You want to start by just telling us your name and who you are?

LOUCKS: Hi. Yes. I’m Peggy Loucks (ph), and I’m 83 years old. And I’m a retired librarian. And I’m the daughter of Allen Ulmer – U-L-M-E-R.

SMITH: When we found out that Al Ulmer’s daughter, Peggy, was still alive, I was thinking, yes. I have so many questions for her.

MALONE: I, on the other hand, was nervous because, look; we don’t need Peggy’s permission to do anything with her father’s character, Micro-Face, since he is in the public domain. But like, look; if she hates this project, I mean…

SMITH: Yeah, it would be a jerk move to be like, tough luck, lady; we’re taking your father’s idea and completely changing it and making a fortune off of it. So we started off with some easy questions for Peggy.

MALONE: Do you know what he thought about drawing superheroes? Did he enjoy doing superheroes in particular, creating them?

LOUCKS: Oh, yes. You know, the – especially some of these characters, they were always in tights with capes and, you know, some kind of headgear or masks.

SMITH: So what was your father like as a person?

LOUCKS: You know, he would’ve been really someone you would like to have known and been in their company. You know, he was a gourmet cook. His beef Wellington was to die for. We always waited for that….

(3) STAY TUNED TO THIS STATION. Amazon dropped a trailer for The Underground Railroad, based on Colson Whitehead’s alternate history novel. All episodes begin streaming on Amazon Prime Video on May 14.

From Academy Award® winner Barry Jenkins and based on the Pulitzer Prize winning novel by Colson Whitehead, “The Underground Railroad” chronicles Cora Randall’s desperate bid for freedom in the antebellum South. After escaping a Georgia plantation for the rumored Underground Railroad, Cora discovers no mere metaphor, but an actual railroad beneath the Southern soil.

(4) AURORA AWARDS. The Canadian Science Fiction and Fantasy Association has announced an updated Aurora Awards calendar.

Nominations will now open on March 27th, 2021. Nominations will now close on April 24th, 2021. The ballot will now be announced on May 8th, 2021.

The Voter’s Package will now be available on May 29th, 2021.

After that date, the calendar will be back on track.

Voting will open July 31st, 2021. Voting will close September 4th, 2021.

The Aurora Awards will be announced at Can*Con in Ottawa, held October 16-18.

(5) PAYING IT FORWARD. In this video Cat Rambo reads aloud her contribution to the collection Pocket Workshop: Essays on Living as a Writer.

One of the great traditions in fantasy and science fiction writing is that of the mentor/mentee relationship. We’re told of many of the earlier writers mentoring newer ones offering advice passing along opportunities and sometimes collaborating…

(6) IT GETS VERSE. [Item by Martin Morse Wooster.] In Isaac Asimov’s autobiography In Joy Still Felt, he reprints part of a poem called “Rejection Slips” where he discusses being rejected by Galaxy editor H.L. Gold.

Dear Ike, I was prepared

(And boy, I really cared)

To swallow almost everything you wrote.

But Ike, you’re just plain shot,

Your writing’s gone to pot,

There’s nothing left but hack and mental bloat.

Take past this piece of junk,

It smelled; it reeked, it stunk;

Just glancing through it once was deadly rough.

But Ike, boy, by and by,

Just try another try

I need some yarns and kid, I love your stuff.

(7) BURIED IN CASH. “How Dr. Seuss became the second highest-paid dead celebrity” at the Boston Globe – where you may run into a paywall, which somehow seems appropriate.

…In fact, according to Forbes.com’s annual inventory of the highest-paid dead celebrities, the guy who grew up Theodor Geisel in Springfield ranks No. 2 — behind only Michael Jackson — with earnings last year of $33 million. In other words, the Vipper of Vipp, Flummox, and Fox in Sox generated more dough in 2020 than the songs of Elvis Presley or Prince, or the panels of “Peanuts” creator Charles Schulz.

And Dr. Seuss stands to make even more money now. That’s because the announcement that six of his 60 or so books will no longer be published has sent people scurrying to buy his back catalog. On Thursday, nine of the top 10 spots on Amazon’s best-sellers list were occupied by Dr. Seuss, including classics “The Cat in the Hat,” “One Fish, Two Fish, Red Fish, Blue Fish” and “Oh, the Places You’ll Go!”

A fortune’s a fortune, no matter how small, but $33 million is a mountain that’s tall. So how does Dr. Seuss continue to accumulate such wealth? It turns out Geisel, who died in 1991 at the age of 87, doesn’t deserve the credit. His wife does. Two years after the author died, Seuss’s spouse, Audrey Geisel, founded Dr. Seuss Enterprises to handle licensing and film deals for her husband’s work….

(8) MEDIA BIRTHDAY.

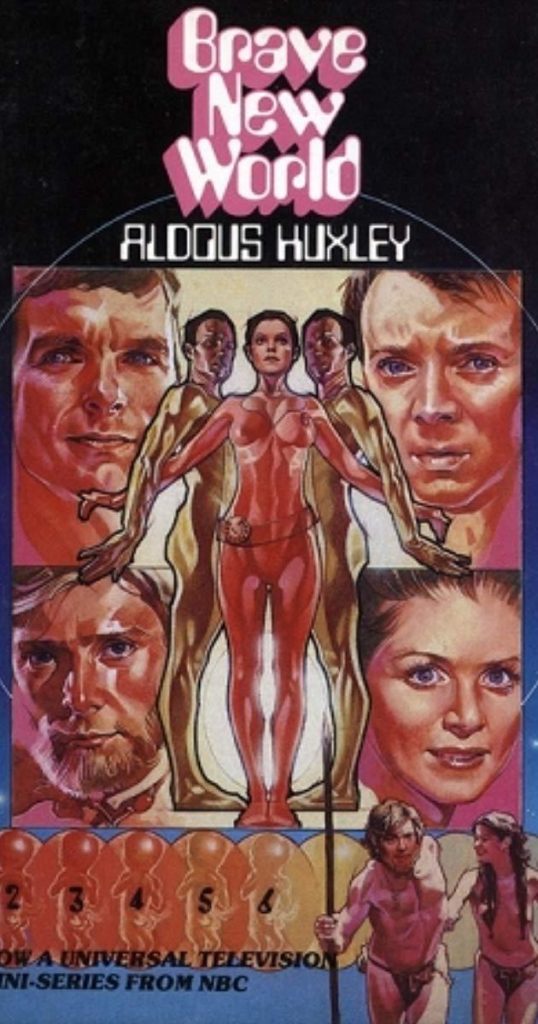

- March 7, 1980 — On this day in 1980, the Brave New World film premiered on NBC. (It would show on BBC as well.) It was adapted from the novel by Aldous Huxley by Robert E. Thompson and Doran William Cannon, and was directed by Burt Brinckerhoff. It starred Kristoffer Tabori, Julie Cobb and Budd Cort. It has a forty-six percent rating among audience reviewers at Rotten Tomatoes. You can watch it here.

(9) TODAY’S BIRTHDAYS.

[Compiled by Cat Eldridge and John Hertz.]

- Born March 7, 1944 — Stanley Schmidt, 77. Between 1978 and 2012 he served as editor of Analog Science Fiction and Fact magazine, an amazing feat by any standard! He was nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Professional Editor every year from 1980 through 2006 (its final year), and for the Hugo Award for Best Editor Short Form every year from 2007 (its first year) through 2013 with him winning in 2013. He’s also an accomplished author. (CE)

- Born March 7, 1945 — Elizabeth Moon, 76. I’ll let JJ have the say on her: “I’ve got all of the Serrano books waiting for when I’m ready to read them. But I have read all of the Kylara Vatta books — the first quintology which are Vatta’s War, and the two that have been published so far in Vatta’s Peace. I absolutely loved them — enough that I might be willing to break my ‘no re-reads’ rule to do the first 5 again at some point. Vatta is a competent but flawed character, with smarts and courage and integrity, and Moon has built a large, complex universe to hold her adventures. The stories also feature a secondary character who is an older woman; age-wise she is ‘elderly,’ but in terms of intelligence and capability, she is extremely smart and competent — and such characters are pretty rare in science fiction, and much to be appreciated.” (CE)

- Born March 7, 1959 — Nick Searcy, 62. He was Nathan Ramsey in Seven Days which I personally think is the best damn time travel series ever done. And he was in 11.22.63 as Deke Simmons, based off the Stephen King novel. He was in Intelligence, a show I never knew existed, for one episode as General Greg Carter, and in The Shape of Water film, he played yet another General, this one named Frank Hoyt. And finally, I’d be remiss to overlook his run in horror as he was in American Gothic as Deputy Ben Healy. (CE)

- Born March 7, 1966 — Jonathan Del Arco, 55. He played Hugh the Borg in Star Trek: The Next Generation and in Star Trek: Picard. That is way cool. He also showed up as on Star Trek: Voyager as Fantôme in “The Void” episode. (CE)

- Born March 7, 1970 — Rachel Weisz, 51. Though better known for The Mummy films which I really, really love (well the first two with her), her first genre film was Death Machine, a British-Japanese cyberpunk horror film which score a rather well fifty one percent among audience reviewers at Rotten Tomatoes. I’ve also got her in Chain Reaction and The Lobster. (CE)

- Born March 7, 1974 — Tobias Menzies, 47. First off is he’s got Doctor Who creds by being Lieutenant Stepashin in the Eleventh Doctor story, “Cold War”. He was also on the Game of Thrones where he played Edmure Tully. He is probably best known for his dual role as Frank Randall and Jonathan “Black Jack” Randall in Outlander. He was in Finding Neverland as a Theatre Patron, in Casino Royale as Villierse who was M’s assistant, showed up in The Genius of Christopher Marlowe as the demon Mephistophilis, voiced Captain English in the all puppet Jackboots on Whitehall film and played Marius in Underworld: Blood Wars. (CE)

- Born March 7, 1903 – Bernarda Bryson. Painter, lithographer; outside our field, illustrations for the Resettlement Administration, like this. Here is Gilgamesh. Here is The Twenty Miracles of St. Nicholas. Here is Bright Hunter of the Skies. Here is The Death of Lady Mondegreen (hello, Seanan McGuire). (Died 2004) [JH]

- Born March 7, 1934 – Gray Morrow. Two hundred fifty covers, fifty of them for Perry Rhodan; four hundred interiors. Also Classics Illustrated; Bobbs-Merrill Childhoods of Famous Americans e.g. Crispus Attucks, Teddy Roosevelt, Abner Doubleday; DC Comics, Marvel; Rip Kirby, Tarzan; Aardwolf, Dark Horse. Oklahoma Cartoonists Associates Hall of Fame. Here is Buck Rogers in the 25th Century. Here is the NyCon 3 (25th Worldcon) Program & Memory Book. Here is The Languages of Pao. Here is The Best of Judith Merrill. Here is Norstrilia. Here is a page from “The Doors of His Face, the Lamps of His Mouth” in GM’s Illustrated Roger Zelazny. (Died 2001) [JH]

- Born March 7, 1952 – John Lorentz, age 69. Active, reliable in the excruciating, exhilarating, alas too often thankless work of putting on our SF conventions, e.g. chaired Westercon 43 & 48, SMOFcon 8 (Secret Masters Of Fandom, as Bruce Pelz said a joke-nonjoke-joke; a con annually hoping to learn from experience); administered Hugo Awards, sometimes with others, 1998, 2002, 2006, 2015; finance head, Renovation (69th Worldcon). Fan Guest of Honor at Westercon 53, Norwescon XXI (with wife Ruth Sachter). [JH]

- Born March 7, 1954 – Elayne Pelz, age 67. Another indispensable fan. Currently Treasurer and Corresponding Secretary of the Southern Cal. Inst. for Fan Interests (yes, that’s what the initials spell; pronounced skiffy), which has produced Westercons, Worldcons, and a NASFiC (North America SF Con, since 1975 held when the Worldcon is overseas). Widow of B. Pelz; I danced at their wedding; E chaired Westercon 55 upon B’s death. Twice given LASFS’ Evans-Freehafer Award (service; L.A. Science Fantasy Soc., unrelated to SCIFI but with some directors in common). Fan Guest of Honor at Leprecon 9, Loscon 13 (with B), Westercon 48, Baycon 2004. Several terms as LASFS Treasurer, proverbially reporting Yes, we have money; no, you can’t spend it. [JH]

- Born March 7, 1967 – Donato Giancola, age 54. Gifted with, or achieving, accessibility, productivity, early; Jack Gaughan Award, three Hugos, twenty Chesleys, two Spectrum Gold Awards and Grandmaster. Two hundred seventy covers, four hundred forty interiors. Here is Otherness. Here is The Ringworld Engineers. Here is his artbook Visit My Alien Worlds (with Marc Gave). Here is the Sep 06 Asimov’s. Here is the May 15 Analog. Two Middle-Earth books, Visions of a Modern Myth and Journeys in Myth and Legend. [JH]

- Born March 7, 1977 – Brent Weeks, age 44. Nine novels, a couple of shorter stories. The Way of Shadows and sequels each NY Times Best-Sellers; four million copies of his books in print. Cites Homer, Dante, Shakespeare, Yeats, Tolkien. “I do laugh at my own jokes…. scowl, change the word order to see if it makes it funnier, scowl again … try three more times…. occasionally cackle…. This is why I can’t write in coffee shops.” [JH]

(10) LIADEN. Sharon Lee and Steve Miller have issued Liaden Universe® InfoDump Number 127 with info about the availability of a new Adventures in the Liaden Universe® chapbook. Also:

LEE AND MILLER PANELISTS AT MARSCON

Sharon and Steve will attending the virtual MarsCon, to be held March 12-14 (that’s this weekend!) Here’s the convention link.DISCON III

Steve and Sharon hope to attend DisCon III virtually. We have no plans to attend in-person, as much as we’d been looking forward to doing so.ALBACON 2021

Sharon and Steve will be Writer Guests of Honor at the virtual AlbaCon, September 17-18, 2021. Here’s the link to the convention siteUPCOMING PUBLICATIONS

The Trader’s Leap audiobook, narrated by Eileen Stevens, is tentatively scheduled for April 11, 2021

(11) PROPS TO THE CHEF. Ben Bird Person shared “My last commission with food illustrator Itadaki Yasu. It’s an illustration of the prop food featured in the original star trek episode ‘The Conscience of the King’ (1966).”

(12) THE BURNING DECK. Your good cat news of the day, from the Washington Post. “Thai navy saves four cats stranded on capsized boat in Andaman sea”. (The article does not say whether the boat’s color was a “beautiful pea green.”)

The four small cats trapped on a sinking boat needed a miracle. The abandoned ship, near the Thai island of Koh Adang, was on fire — sending plumes of thick black smoke into the air as the waters of the Andaman sea rose around them. The ship was not just burning: It was sinking. And it would not be long until it disappeared beneath the surface.Wide-eyed and panicked, the felines huddled together. When the help they so desperately needed arrived, it came in the form of a 23-year-old sailor and his team of Thai navy officials….

(13) GOOD DOG. In the Washington Post, Steven Wright says video game developers are making an effort to have animals in the games that you can pet and interact with but that it takes up a lot of additional pixels since the designers are trying to make the games realistic and are using tons of pixels having characters run and blast foes. “The ‘Can You Pet The Dog’ Twitter account is having a big impact”.

… Tristan Cooper, who owns the Twitter account “Can You Pet the Dog?,” never set out to create a social media juggernaut. Rather, he was just trying to point out what he felt was a common quirk of many high-profile games: While many featured dogs, wolves and other furry creatures as hostile foes of the protagonist, those that did feature cuddly animal friends rarely let you pet them. Cooper says the account was particularly inspired by his early experience with online shooter “The Division 2.”

… However, as the account quickly began to grow in popularity, Cooper and others began to notice a subtle increase in the number of games that featured animals with which players can interact. To be clear, Cooper doesn’t wish to take any credit for the proliferation of the concept, despite the obvious popularity of the account. (“Video games had pettable dogs long before I logged onto Twitter, after all,” he wrote. “That’s the whole reason I created the account.”)

However, he and the account’s fans do sometimes note the timing of these additions, particularly when it comes to certain massive games. For example, he notes that battle royale phenomenon “Fortnite” patched in pettable dogs only a few weeks after the account tweeted about the game. And “The Division 2” finally let you nuzzle the city’s wandering canines in its “Warlords of New York” expansion, which came out in March 2020 — around the same time Cooper was celebrating the year anniversary of the Can You Pet The Dog? account….

(14) WHAT’S THE VISION FOR NASA? [Item by Martin Morse Wooster.] In the Washington Post, Christian Davenport says that the increasing rise of private spacecraft with a wide range of astronauts as well as cost overruns in its rocket development programs is leading the agency to do a lot of thinking about what its role in manned spaceflight should be. Davenport reports a future SpaceX mission will include billionaire Jared Isaacman and will be in part a gigantic fundraiser for St. Jude’s Children Research Hospital (a St. Jude’s physician assistant will be an astronaut as will the winner of a raffle for another seat). “NASA doesn’t pick the astronauts in a commercialized space future”.

… And it comes as NASA confronts some of the largest changes it has faced since it was founded in 1958 when the United States’ world standing was challenged by the Soviet Union’s surprise launch of the first Sputnik into orbit. Now it is NASA’s unrivaled primacy in human spaceflight that is under challenge.

… In an interview, Steve Jurczyk, NASA’s acting administrator, said the agency is well aware of how its identity and role are changing, and he likened the agency’s role to how the U.S. government fostered the commercial aviation industry in the early 20th century.

NASA’s predecessor, NACA, or the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, “did research, technology development to initially support defense … but also later on supporting a burgeoning commercial aircraft industry and aviation industry,” he said. “So that may be how we evolve, moving forward on the space side. We’re going to do the research and the technology development and be the enablers for continuing to support the commercial space sector.”

… But NASA officials are concerned that much of the future workforce is going to be attracted to a growing number of commercial companies doing amazing things. There is Planet, for example, which is putting up constellations of small satellites that take an image of Earth every day. Or Relativity Space, which is 3-D printing entire rockets. Or Axiom Space, which is building a commercial space station. Or Astrobotic, which intends to land a spacecraft on the moon later this year.

The question NASA faces, then, is an urgent one: “How do you maintain that NASA technical expertise?” Jurczyk said.

The agency does not know….

(15) YOU COULD BE SWINGING ON A STAR. OR — Ursula Vernon could no longer maintain what critics call “a willing suspension of disbelief.”

Commenters on her thread had doubts, too. One asked: “Were any special herbs or fungi involved before this message was received?”

As for the possibility of putting this phenomenon to a local test —

[Thanks to Andrew Porter, John Hertz, Ben Bird Person, Martin Morse Wooster, Michael Toman, John King Tarpinian, Cat Eldridge, JJ, and Mike Kennedy for some of these stories. Title credit goes to File 770 contributing editor of the day Daniel Dern.]

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

@John A. Arkansawyer: I said I had a similar reaction; please don’t presume to tell me what I am or am not chiming in with, simply because it’s not 100% the same thing. What I was reacting to was Sunkara mocking an immediate concern people have—being treated with racial bias as an employee or a customer—because he thinks addressing this is a distraction from addressing the entire economic system. And I don’t think “mocking” is too strong a word, as he flippantly dismisses the whole idea of anti-bias efforts within companies as if it’s an arbitrary thing “liberals” care about rather than real radicals, with the strong implication that they care about it only because it makes them feel better about big corporations. This is all very much in line with the reductio-ad-absurdum version of the “class, not race” argument that a small segment of the US left, commonly but not exclusively associated with Jacobin, unfortunately likes to use to dismiss anti-racism efforts in general—a way of saying that all other activists are doing it wrong. I really don’t think it’s a stretch for me to liken it to an argument that making it possible for authors to earn a living is just a distraction from the real work of entirely dismantling capitalism.

Sunkara’s argument—and, again, I don’t feel compelled to take this kind of thing incredibly seriously from someone who’s been at the head of his own company for literally his entire career and has never engaged with politics in any way other than publishing a magazine, but even taken entirely on its own merits I think the problems are clear—also falls apart as soon as one notices that it’s not only employees of large companies who are affected by bias within those companies. He hand-waves this away by saying in effect “Well yes, there are also customers of those businesses who might suffer from their racism— but, lots of people are too poor to be customers, so that’s just a distraction too.” This is exactly akin to saying that the civil rights movement was just being a bunch of bourgie liberals by having sit-ins at diners or on buses, because what about the people who don’t have access to diners or buses anyway. It also (very ironically for a self-styled socialist) completely ignores the fact that anti-bias efforts also happen within government agencies and public institutions that affect the lives of millions of people regardless of whether those people are buying anything, and that the right wing mocks those in virtually the same style that Sunkara mocks them in from the left, without the “we’ll fix it by getting rid of capitalism” bit of course, but with the same sneering about how “micro-aggressions” are irrelevant.

There is an endless list of whatabouts that can be put in front of anyone else’s demand for fairness that one doesn’t wish to listen to.

@John A. Arkansawyer: It’s not my wish to derail the comments here with an argument about Jacobin or the proper approach to socialist action; I realize that those never go anywhere and that’s not what this blog is about. So I won’t engage with any further responses about that— carry on if you want to, I’ve said my piece. I’ll just sum it up like this: while “we should address the root causes of X rather than only immediately addressing X” is a valid point of view, it is way too easily twisted to mean “anyone who wants to address X is missing the point” and, not surprisingly, that rhetorical approach is often used by people who don’t have much personal experience with X and aren’t interested in others’ experience.

@ Eli

I totally agree. The leftists at Jacobin like to kiss away lots of systemic problems by waving a magic wand and eliminating capitalism. I don’t think it will ever work that way—you won’t find that wand at Mugworts.

Eli, I have my issues with Sunkara’s politics at times, along with some of the political tendencies that can be found in the writers at the Jacobin, but I’m not seeing a very substantial engagement with what is on the page. The critique doesn’t seem to be directed towards those who experience racist discrimination either as workers or as customers, but towards a particular framework of addressing those issues. The essay even points to empirically driven research that seems to show the limitations of that approach. One of the significant points is not only that it potentially has limited effects, but the current solutions don’t even succeed in those limited effects. It then goes on to critique some of the commodification of dissent that we have seen recently. I do think that there are some issues with the essay. It leans a bit too heavily on the history of union organizing as a solution, which ties into a tendency to ignore or minimize the racist elements of the New Deal, including the NLRA. The work would do better to look to the collective projects of the civil rights movement or present anti-racist projects to oppose the business model that is being critiqued, but that requires engaging in the substance of the argument rather than not liking Bhaskar Sunkara, which feels like a bit too much of the motivation of the response.

I think the problems with copyright as it stands down can be boiled down to two elements: The fact that software is copyrightable, and the length of work-for-hire copyrights (which effectively means corporately-owned copyrights).

I also believe that laying out exactly what sort of changes are being talked about is useful for assessing the situation. The first proposal has been for a single 30 year term for copyright. 30 years ago was 1991. If that was in effect, that would mean that any book, movie, song, or piece of art that was put out prior to 1991 would now be out of copyright. That would mean Star Wars would be out of copyright. So would every Beatles song, as well as every song McCartney made with Wings and most of his solo work.

On the upside, this sort of shortening of copyright might mean we could get an intact DVD version of WKRP in Cincinnati, since the music rights issues wouldn’t be present. On the other hand, no one actually involved with the production of WKRP in Cincinnati would be likely to benefit from such a release. One can argue over which option is better, but having that out in the open means everyone basically knows what the stakes are.

Even the longer proposal of two consecutive 18 year terms would result in pretty much all of these works being out of copyright.

As an initial matter, I don’t think shortening the term of copyright would benefit individuals so much as it would benefit corporations – mostly those involved in movie and television production. I don’t really think there is a groundswell of authors desperate to write stories using other author’s work, but there are almost certainly a bunch of production companies looking to make movies and television shows out of published books. Right now, if a production company wanted to make, say, an Elric of Melnibone series would have to go to Moorcock and get him to agree to sell the rights to them. If copyright was significantly reduced in length, they could make the series and Moorcock wouldn’t see a dime from it. Effectively, I think that shortening copyright significantly would a great boon to corporations that make inherently derivative works.

I don’t even think shortening copyright would significantly affect Disney, who is the monster that looms large in the background of any copyright discussion. Disney isn’t a media company. They are, by revenue, a parks and hospitality company that has a comparatively small media division. Losing the copyright on Steamboat Willie would bother them some, but mostly what it would mean is that others could use it in public performances. But Mickey would still be protected, because he is not merely in copyrighted work, he is also trademarked. Disney would still make all of the money it wants to selling items with Mickey (and most of the rest of their recognizable characters) on them, and they would still be able to prevent others from making such things due to trademark law, and since they make a lot more of their money selling stuff in their parks than they do on Disney cartoons, shortening copyright probably wouldn’t hurt their bottom line too much.

And then you get to software copyrights, which is a subject so complicated I don’t even know where to begin other than to say I don’t think copyright is a very good means of protecting the intellectual property of software and some other means should be developed specifically for it. That is probably beyond the scope of a comment like this.

Basically, this is a long way of saying that I would shorten corporate copyright to something like 50 years, and keep individual copyrights at something like life +35 or life +50, and make them subject to a single posthumous transfer, so an author’s immediate heirs could benefit, but no farther. And I would take software and construct an entirely different regime of intellectual property protection for it.

@cat Moon’s science fiction stores are great, but even more impressive to me are her original Paksenarrion trilogy and the five-volume Paladin’s Legacy follow on which is just amazing.

@Aaron:

We already have a mostly intact release of WKRP. Not completely, as there were a handful of holdouts, but the vast majority of the music got cleared, and the exceptions did not impact my enjoyment one bit. (Yes, I own the box set, and I watched the whole series almost as soon as I got it.)

Further, I don’t see “copyright should be shorter because then obstinate rights-holders couldn’t pose an obstacle to corporate greed” as a winning proposition, and that’s what the “WKRP could use all of the original music on DVDs” model amounts to. If a property is valuable enough to merit a DVD release, the holders of the music rights deserve to get paid. It’s not their fault the corporate contract writers of the day were not canny enough to purchase those rights. Yes, this might drive the price of the box sets up, but that’s what negotiation is for. It’s better to get a nickel on a released product than a dime on one that’s never made.

As for what I’d like to see happen with copyright? I think that it needs to last for at least one complete nostalgia cycle, to allow creators to profit from “sleeper” hits. I’d also like to see software treated differently from poetry and prose, as well as a provision for “abandonware” in all three cases.

In short, as much as I loved the Apple II games I played and utilities I used in high school, both the hardware and the software have been discontinued for decades. At least the software should be in the public domain by now. A short story, song, or novel from the same time, though? No, that’s too short.

And to go on the record by putting my money where my mouth is: if I should happen to die with completed works on my hard drive but no estate to oversee or benefit from them, I’m fine with them getting put into the public domain. For that matter, it is a virtual certainty that I will never finish fleshing all of the story seeds in my notes out into finished stories. I have no issue with those getting released to the world after my death, so others can write the stories I never got to, but I would like an acknowledgment and/or a line on the copyright page for any which do make it to fruition. Seems only fair, not that I aim for any of that to become an issue anytime soon.

@all, unrelated:

I just finished watching the second episode of NBC’s new Debris series, and I have a question – not a spoiler! – that I’d like to toss to the Filers and see if anyone’s got an answer.

The first two screens of both episodes establish that (a) three years ago, telescopes picked up a damaged alien spacecraft moving through the solar system and (b) debris from it has been falling to Earth for the past six months.

So my question is… HOW? What possible path can this ship be following that makes this possible? There’s no mention of the ship being captured into Earth orbit, and on even the most favorable unpowered path, Earth would have to be emerging from the field Real Soon Now… but there’s no indication that this is the case. Indeed, the series premise appears to be that the fall of debris is going to continue indefinitely.

Am I the only one grinding my teeth over this detail?

Some of Scalzi’s arguments seem a bit disingenuous, such as saying that the US’ hands regarding duration of copyright terms are tied anyway because of the international treaties they are subject to — as if the terms of those treaties had not been negotiated under substantial US influence in the first place, and were not sometimes enforced on reluctant parties with substantial US pressure.

I usually find myself on tech sites being a minority voice in favor of copyright against hordes of “Information Wants to Be Free / Musicians Should Live Off T-Shirt Sales / Programmers Should Eat Bitcoins” techbros, but at the same time, I think copyright terms have grown excessively long, and the erosion of the public domain and of fair use rights is a real problem.

One of the biggest problem with long copyright terms, in my opinion, is not even in having to pay the heirs of an author for a work — in most cases I’d be glad to do so, but so often I don’t even get the opportunity to do so, because the work for decades gets stuck in a limbo where it’s no longer worth publishing commercially, but cannot legally be published non-commercially. Maybe the problem is particularly acute in a small market such as Switzerland, but it’s absolutely crazy how novels like “Die Sechs Kummerbuben” are not in print.

@Cat Eldridge: (Simak Meredith moment)

I found no less than FIVE of Simak’s short fiction collections available for $1.99 each on Amazon today, including the one you cited. Together with the one I already owned, that nets me half of the volumes in that series.

@No one in particular–

My $0.02 worth on copyright, and why, in one particular instance, I am very annoyed with it:

I tend to collect DVD series of old television shows I was fond of when I was a kid. I buy brand-new, legit copies partly because it’s the right thing to do, and partly because of good production quality.

That said, there are four shows I have never been able to find legit copies of. One is “Twelve O’clock High.” I have no idea why that one has never been available, but it isn’t, never has been. The other three are a trio of wonderful (to me) private eye shows produced by Warner Brothers from the late 1950s through the early 1960s: “77 Sunset Strip,” “Surfside 6,” and “Hawaiian Eye.”

None of those three WB shows has ever been released on DVD. I have run across two ideas as to why not, and both revolve around the live-music scenes that ran through all of them. One is that WB has found it impossible to track down the rights holders to the music they included–to which I wonder how they got the rights to show the music in the first place. The other is that one or more music persons involved in the production of those shows (or his/her heirs) flat refuses to allow the shows to be reissued.

Both problems involve copyright, and both are very, very frustrating to a legitimate customer who wants to pay the proper amount of money to the primary rights holder (WB) to purchase copies of their old shows for home use.

I’ve managed to find copies of all of these shows via gray market, and have purchased such, but I’m not satisfied. Gray-market quality is very spotty. I’d really like to own legit, high-quality copies. And WB, because of rights hassles, either won’t or can’t provide what I and many other prospective customers want. These were not fluffy flops. They were top-rated shows in their day.

So, normally I think copyright is a good thing, but in this case, rights issues keep me from buying legitimate, quality copies of something that would be available but for rights issues.

Other studios had no trouble putting out complete sets of shows like “Perry Mason,” “The Man from U.N.C.L.E.,” and “The Untouchables.” Not to mention “The Twilight Zone” and “The Outer Limits.”

So, I am supremely annoyed at copyright, in this particular situation.

One of my channels briefly had “77 Sunset Strip” as well as Route 66.

I preferred 77 because it just seemed so over the top–almost like the Lucy episode where they went to a coffee-shop and found themselves surrounded by ‘beat-nicks’.

But that was apparently an aberration because I’ve been looking for them ever since.

1). I’m not sure why they seem to think there’s a dearth of writers unable to turn out new work. If my bedside table, dresser top and other flat surfaces around here are any indication , I’m having enough trouble keeping up now.

I’m kind of wondering who these poor creative types are who are apparently unable to work because other people’s copyrights are preventing them from making a living or something.

As far as I can tell, they can still write all the various tropes around; they just can’t use other people’s characters.

@Jeanne (Sourdough) Jackson–You seem to be overlooking what seems to me to be a glaringly obvious possible reason for those shows to not be available in legit, high-quality copies.

They may not exist, or not enough of the run of the series to be perceived as commercially viable. An awful lot from the 50s and early 60s doesn’t. Kinescope didn’t produce high-quality copies, and even after Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz started filming I Love Lucy rather than kinescoping the broadcast, it took time for that significantly more expensive process to spread through the industry.

And the rerun market, making that an obvious source of future revenue, couldn’t take off until filming shows properly had reached a certain critical mass. Until that did happen, and was firmly enough established that even the less quick-minded caught on, even shows that did get filmed were at some risk, after cancelation, and after the first flush of the rerun market for them had passed, of their space-eating canisters of film being perceived as excess, before the appetite for “classic” shows took off.

I’m curious why some people think software deserves less copyright protection than literature, TV shows and movies.

Software dates more quickly than any of those, both in terms of the platform that supports it and in its features. Comparisons are difficult, but it seems to rack up more abandonware (which is primarily a software term, in fact), including for well-known work, than the others.

Whether these add up to a difference in principle is another question, but they are practical differences in the market.

I hear you on the practical side. But, for example, there’s been a growing interest in old computer games and many are available to run on an emulation platform. I think strictly speaking these should still be under copyright. They are in effect products of piracy (something which, in the context of games, has always seemed acceptable to a large fraction of the game-plating population). That being said, there’s no practical way to ensure royalties can be paid to the original authors, since the publishers, distributors etc are long gone.

Software is far more like other inventions, whose innovations ought to become available for use by others, to keep innovation and technical progress moving forward, than it is like a good book, or song, or other varieties of art.

@Sourdough: “One is that WB has found it impossible to track down the rights holders to the music they included–to which I wonder how they got the rights to show the music in the first place.”

You’re talking about shows made well over half a century ago. Original rights holders have this nasty little habit of dying in that kind of time frame, and tracking down their heirs is a nontrivial problem. As to how the shows got the rights in the first place, broadcast and syndication rights do not cover reproduction on home video media. Thus, acquiring the first set decades ago does not help at all with getting the second set now.

Or, in lay terms, getting permission to borrow your car twenty years ago does not tell me who owns the car now, and it certainly doesn’t entitle me to just take it for a spin today.

Let’s also note that, in the 50s and early 60s, neither the makers of the shows, nor the owners of any other intellectual property used by license within them, had any reason to be thinking about the home video market as it now exists.

@Lis Indeed, c.f. the BBC not saving episodes of Doctor Who (most famously) and many other programs.

Genuine innovations in software tend to be protected by patents which, as others have noted, have a much shorter duration than copyright.

Let’s also not forget that ‘tracking the rights owner’ can be more complicated because those rights can be sliced up and sold to different companies over the years. If any of those companies goes out of business then it can be extremely difficult to find out who/what owns and/or licenses that slice of rights. Nowadays, to release something the company wants to be certain that all of the rights are in hand so there aren’t any nasty surprises in the future.

But the real issue behind the lack of release of shows like the ones we’re talking about is not the owners wanting more cash than the companies are willing to pay. It’s that the companies are trying to buy out unlimited rights, often including the right to use the song/character/scene to market third party products, or the right to create all new content based on the song/character/show. Combine that with how companies try to shed themselves of obligations to rights creators by “selling” the content to a sister company conveniently without including the obligations (like what’s happened to Alan Dean Foster) and people aren’t willing to play along with the legal theft of their work.

The ‘problems’ with copyright that keep coming up are clearly due to shenanigans by companies not individuals, so why we keep discussing solutions that limit the rights of individuals is beyond me.

@Lis and Paul Weimer – And it’s not just the episodes, but the paperwork relating to the show that has also been tossed. Meaning there’s no way of being certain what happened to the rights.

I’ve worked for companies trying to develop concepts based on public domain stories/shows and it is by far more difficult than it seems. We had trouble finding proof that shows made in the 1910s were actually fully in the public domain sufficient to convince our lawyers that the company wouldn’t end up liable for costs that outweighed earnings.

I demand satisfaction. Pixels at dawn.

I think it’s far more likely that these old shows just were never preserved in a more durable format than that it’s a rights issue. Most really old tv has disappeared, along with a lot of movies for this reason. However, FWIW, Route 66 is available on one of the weird little streaming apps (a free one). I can’t recall the name offhand but I found it through the FireTV ecosystem.

With tv shows there is also the issue of residuals as well as copyright. I am aware of BBC programmes that have not had a DVD release because the cost of tracking down who to pay residuals to for now deceased or otherwise unlocatable performers would be prohibitive. In these cases there was no copyright issue involved as the DVD would have been issued or licenced by the BBC who own the copyright (for example, one programme has had series one and two issued on DVD but the releases of series three and four were cancelled for this reason).

As far as length of copyright is concerned, a lot of comments have considered providing support to a writer’s offspring until maturity. However, suggesting 18 or 25 years as suitable for this doesn’t take into account that support for a writer’s spouse in old age may be cut off.

In the IT shop I used to work for, we had a way of dealing with undocumented or poorly-documented stakeholders when making system changes. First, we announced the proposed changes and held a meeting of all who might have an interest. We also watched to see if anyone squawked about the proposed changes. If no squawks, and no negative feedback during the meeting, we made the changes. Then we watched again for anyone who squawked. Then we dealt with the complaints.

In a studio situation, “dealing with the complaints” would probably include payments to the otherwise-lost copyright holders. Bear in mind that such copyright holders will not get one thin dime if there is no new commercial distribution. Neither will the studio–its intellectual property is commercially worthless if nothing is done with it. And the potential customers won’t get any product to purchase. Nobody wins.

So, I don’t see why the studios don’t take the path my IT shop did. As for lack of copies to use for masters–those gray-market bootlegs I bought came from somewhere, probably somebody taping off the air during reruns after VHS became common. There had to have been kinescopes, films, or (later on) videotapes. Also, the gray-market copies exist–if there are no others available, the studios could, in theory, purchase those, and run digital cleanup on them.

@Jeanne (Sourdough) Jackson–The kinescopes or films did exist at one point, but you’re talking about shows from before they had any recognized commercial value after the run of the show was over–often cancelled because viewership, to the extent they could measure it then, had dropped below what were considered acceptable levels.

This resulted in a lot of those kinescopes and early films getting dumped to free up space. Or if not actively dumped, they just got lost track of, because they weren’t seen as important. I.e., yes, they did exist, but now they don’t exist.

As for the gray-market bootlegs–tracking them down, buying them, doing digital clean-up on them–how much are you going to be willing to pay for the resulting sort-of-acceptable videos? How many other people are going to be willing to pay for them? That’s an awful lot of work, and an awful lot of expense, for the studio to expend on something they may see as having a low likelihood of being commercially viable.

As for unknown rightsholders, entertainment lawyers and accountants tend to be risk-averse. They don’t know how many people might come out of the woodwork, or how many who do will have any idea how the market for videos of old tv shows work, or any realistic notion of what the properties are worth. That could make reaching agreement with them difficult and expensive out of all proportion to what the properties will earn in any reasonable length of time.

In regards to notifying potential rights holders and waiting for complaints – there’s no way of knowing who is a potential rights holder if the documentation is missing. It’s not as easy as notifying employees, stockholders and vendors. We’re talking about potentially anyone, anywhere in the world.

In regard to upconverting old product to 16×9, HD, with 5.1 sound (the standard tech spec for most streaming companies), I have some experience with that. It’s an effing nightmare. You usually don’t have one high enough quality dupe or master in the vaults so you end up trying to Frankenstein together a product from different video and audio sources. It also costs quite a lot – our minimum cost for a 90 minute program was $15,000 and could cost significantly more depending on what we were dealing with. And I’m not talking about a remastering – that’s so much more expensive. I’m talking about a simple (hah!) upconvert from tape.

The license fees we could expect from digital streaming companies for old content was around $2,000-$5,000 for a 2 to 5 year license if they were willing to take it at all. This was for 10 year old content that had been stored in climate-controlled vaults by Hollywood studio professionals. I’ve worked on more than one project that was killed as soon as costs hit a certain point.

If there was a risk that the company would get sued by an old license holder or by an old actor with a residual claim, then the risk of selling the product was higher than potential earnings. $500/hour lawyer fees can blow up the loss to the company all by themselves and that’s if the company settles as fast as possible.

There are so many moving parts and potential pitfalls that have nothing to do with the copyright holder. The argument that limiting copyright terms would make putting out these old shows more likely is just not logical.

@Lis Carey and Lorien,

I see your points. It still bothers me that I’ve been able to purchase legit copies of the complete Twilight Zone, Untouchables, Perry Mason, 87th Precinct, and Car 54, Where Are You? which are from the same time period–but not these three immensely popular (in their time) private-eye shows.

I am thankful that somebody managed to make gray-market bootlegs of them (and also of 12 O’clock High and Rescue 8). My conscience doesn’t bother me, since the studios insist upon sitting on their hands. I just wish I could buy legit copies that are of better quality.

77 Sunset Strip was rerun in Germany in a graveyard slot in 21st century. Furthermore, it’s coming out on DVD in three volumes in Germany in July 2021 and a soundtrack CD is also available. So they must have found some way to deal with the music rights.

Of course, the German TV reruns and DVD release are based on the West German broadcast from the 1960s, which was preserved (West German TV was pretty good about preserving tapes, though much of the East German film and TV archive was destroyed in the 1990s). And indeed, some Doctor Who episodes only survived because of a broadcast in a different country and could be restored via the tape recordings of episodes made by fans. However, I strongly suspect that no one made extensive tape recordings of the US broadcast of 77 Sunset Strip, so this route is closed, since I doubt American viewers want to see the German dub of 77 Sunset Strip, even if it was very good. One of the voice actors was the legendary Hans Clarin.

Regarding the lost BBC tapes, I actually helped to recover some lost BBC programs. I was on the staff of the university literary magazine and organised our regular booksales. We stored the equipment and the cash box in the office of a professor of English literature. One day, while putting away the books and the all important cash box, I chanced to notice a few old film reel cans in the storage cabinet and asked the professor about them.

“Oh, those are just some old black and white movies I used to show in class”, he told me, “I no longer use them and we don’t even have the equipment anymore to play them, but it feels like a waste to throw them away.”

Me, excited: “Are those perchance BBC productions?”

Professor: “Yes, they are. But they’re really old.”

Me, even more excited: “The BBC dumped a large part of their archive in the 1970s and are now missing a lot of old programs. They want them back and are actively searching for any tapes that might have survived.”

Anyway, I gave the professor the contact info of the people at the BBC in charge of recovering lost tapes, who were very happy to get those old film reels back and send the professor a VHS or DVD copy of the films he’d returned. Of course, it wasn’t Doctor Who or anything similarly cool – it was just a few documentaries about farming and WWI and I forgot what the last one was. But I still helped to recover and preserve them for future generations.

The category of “Things I ought to be able to buy legit copies of, except for the rights issues,” however frustrating it may be, also includes inside its Venn circle “Things the rights holder chose not to make available for purchase at this time, nor to preserve it for future generations, which is their right.” (Like the Seuss 6!) There’s no “unless I really really really want to purchase them, which desire morally obligates the rights holder to either make them available for me to purchase, or else have no complaint about my making bootlegs” exception.

I don’t think anyone would argue that it would be OK for some rando to print new copies of the Seuss 6, whether to sell or to distribute for free like pamphlets, and say “Well, since the rights holder won’t make them available…” for example. Nor would it have been right for Pratchett’s family to ignore his wishes about destroying his unfinished manuscripts, saying, “But future generations!” So I guess I don’t see a moral difference between that and “the copyright holder failed to create a legitimate way for me to buy it, so I’m going to bootleg it, because my right to have a copy supersedes their right to control its availability.” To say those are different cases seems to me to say that the rights holders only get to exercise their rights if we approve of how they do it, and why. And that’s not how copyright works. (It’s not how most property laws work, either. It’s certainly not how consent works.)

I mean, yes, I’m probably going to feel less guilty about violating a corporation’s copyright than an individual’s. Depending on the corporation. Depending on the individual. And I’d like to see adjustments to copyright law for recognizing the difference between creators and those who prey on creators, or offering better remedies for unexpected rights boondoggles beyond “Well, you should have expected it and edited the contract to cover it”. And I’m not going to go scold bootleggers or authors or whoever for handling such situations in “irregular” ways. But I really feel like I’m standing in a glass house if I get too blithe about, “Oh, that copyright is all right for me to violate, because reasons.”

CAVEAT: The above is not intended to get into the weeds of all the ways TV shows fall out of circulation due to things not under rights holders’ control, like aging technology and so on. I acknowledge that. Others are handling that discussion ably and do not need my half-assed input. That is all. Thank you.

I’m upset to this day that there is no intact copy of the 1980 Lathe of Heaven, due to PBS’s utter lack of commercial instinct.

It’s not just that they couldn’t afford to keep the rights for the Beatles’ song and had to replace it with a (lousy) cover in the DVD…that’s understandable. What REALLY bugs me is that they placidly lost the master tapes and had to eventually piece a new copy together from other people’s VHS tapes, losing footage in the process. There’s a bit where George Orr and Heather Lelache are riding a monorail to Haber’s institute while the world is falling apart and Mount Hood is erupting outside the window, and an old lady passenger quavers “Nothing seems to go quite RIGHT today,” which was just perfect in the original and gone from the DVD version that I saw.

I may be a bit overemotional about it, but that film was perfect in its low-budget way and it was my gateway drug to Ursula K. Le Guin, so it still hurts.

@Sourdough: “Then we watched again for anyone who squawked. Then we dealt with the complaints. […] So, I don’t see why the studios don’t take the path my IT shop did.”

Because, in the studio case, it’s illegal. Simple as that.

@jayn–I’m totally with you, on the loss of the 1980 The Lathe of Heaven.

Complete audio survives for every episode of Doctor Who, thanks to fan recordings, though 90+ episodes are missing in visual form. Who is often mentioned in conjunction with missing episodes because it’s of particular fan interest, but that’s a better position than many contemporary shows.

Hampus Eckerman on March 8, 2021 at 4:16 am said:

“Someone has not heard of Project Gutenberg.”

As an almost daily user of Gutenberg, I’m well aware of it. But this is not really about putting free digital copies of works, whose copyright is lapsed, available online for people to read or download. Nobody loses or wins financially.

This is about people making money out of authors’ works, and how long the authors or their heirs should be among those people making money.

When the Internet Archive – most of whose old books will never be republished by commercial publishers – put online works by still copyright protected authors, living and dead, the reaction was justifiably fierce by both from authors and publishers.

@Aaron

There’s at least one more problem: Orphan works. At some point well before (life + 75) or (creation + 95), if no one actively claims “this work is mine” by registration or other means for decades, then the copyright should be viewed as “abandoned” and available for exploitation by others.

That would be a good thing. Look at all of the fan-made Star Wars films that have been produced by amateur filmmakers, some of which are quite good. Now consider what could have been made by professionals with the incentive of above-board profits. Disney made an empire turning public domain fairy tales into classic animated films; what movies (and other works) could Star Wars generate? (And how many jobs could be created by making them?)

@microtherion

The Berne Convention is what modern Western copyright law conforms to. It was created in 1886; the United States did not join it until 1989 (and is still not fully compliant with it).

@Rev. Bob

And then shouldn’t the inventors of the laser technology that makes DVDs possible continue to get paid, even though their patents have expired?

All IP protection is a balancing act between incentivizing creators, and allowing the public maximum benefit. The only argument for lengthy copyright is that it incentivizes the creation of works that would not otherwise get written or drawn or sung or filmed if the copyright term was shorter. If you can make the case that Andy Weir wouldn’t have written The Martian if his grandkids wouldn’t be making money off it decades after his death, then that’s an argument for (life + many years). An income stream for his grandkids it is not in and of itself a reason for copyrights to be long (nor, for that matter, is a retirement income for Weir or his spouse) . (Especially when you consider that the vast majority of books are published and then go out of print, and never make any more money after that. Why should copyright law be based on the economics of exceptional works, rather than the routine ones?)

@Jeanne (Sourdough) Jackson

Perhaps the solution for this is some sort of compulsory licensing such as exists with music (your local bar band can play a cover of “Free Bird” without Lynyrd Skynyrd’s specific permission; the ASCAP or BMI license held by the bar pays money to the band. And radio stations can play Skyryrd’s own recording without specific permission).

@Cliff

Why should it be the same? IP law treats inventions different from novels, logos different from drugs, audio recordings different from video recordings, in-print books different from out-of-print books.

But a specific answer is that software has a public utility that novels do not, thus the balancing act of “length of time for creators to hold exclusive control” vs. “how soon should it go into public domain for 3rd parties to exploit” (which is what congress decides when it sets copyright lengths) is different.

@Nicole J. LeBoeuf-Little

If you are arguing that creators have an absolute right to take works out of distribution and push them down the memory hole, never to be seen again, I’ll take the contra-position. The whole philosophical/legal justification for copyright is that society grants creators exclusive rights for a period of time in order to incentivize creators to generate material that benefits society. See, for example, the language of the copyright clause in the U.S. Constitution.

So if an author enjoys the benefits of a copyright (royalties, protection from pirate works, etc.) then they have an obligation to allow society to enjoy the work.

@Rev. Bob

You’re making the argument for shorter copyright terms here. When the reality of how copyright holders maintain and store their works means that you can’t pay royalties anyway, then the terms are too long.

Most silent movies are lost, never to be seen again. The fact that we have as many as we do is because of “pirates” who kept and copied films clandestinely. If it was easier for 3rd parties to exploit materials (from shorter copyright terms, compulsory licenses, or other means), we’d have high quality copies of more of these TV shows to watch today.

The reality of today’s commercial exploitation of IP content in the US is that the copyright is separated from the right to commercially exploit, distribute or license the content for use. Some of those contracts run for very long terms, some even in perpetuity. These contracts usually also include the right to create derivative works based on the original content, or at least a mandatory first offer, first refusal or first look at subsequent works.

Since that’s the case, it doesn’t matter if copyright terms are shorter or not. The company holding the publication or distribution rights can stop any works being created based on the original content. THERE is your issue preventing people from creating new content on works that have entered public domain. Until that end of things is dealt with, there is no point to shortening copyright terms. Unless your point is to advantage media companies at the expense of content creators.

If I’m not a party to the contract, it doesn’t restrain me. Copyright is what restrains me.

Federal copyright law pre-empts state contract law.

This is from the Nevada Law Journal:

Policy Against Extension of Copyright Duration

Attempts to contractually extend the Act’s grant of monopoly rights by requiring royalties to be paid for use after copyright expiration should be unenforceable per se as violative of the clear public policy against extending copyright duration. Here, as in patent law, the statutory terms can be viewed as quid pro quo for the grant of monopoly rights.

[A]ny attempted reservation or continuation… of the patent monopoly, after the patent expires, whatever the legal device employed, runs counter to the policy and purpose of the patent laws …. By the force of the patent laws…is the invention of a patent dedicated to the public upon its expiration …. [The patent laws] … do not contemplate that any one by contract or any form of private arrangement may withhold from the public the use of an invention for which the public had paid by its grant of monopoly ….

Thus, by analogy, the force of the copyright law itself prevents extension of the copyright monopoly in time. Regardless of the situation of the parties or the circumstances surrounding the agreement, an agreement to extend the duration of the copyright monopoly is unenforceable per se. State contract law that would allow enforcement of contract terms specifying indefinite or extended royalties should be preempted. In April Productions, Inc. v. G. Schirmer, Inc.,the highest court of New York State held that federal copyright law required royalties to end at the expiration of the copyright term if no earlier date was contractually indicated. The court also indicated that an express provision purporting to extend royalties beyond expiration might be unenforceable per se under copyright law.

https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/33140187.pdf

(14) From the quoted article:

“Now it is NASA’s unrivaled primacy in human spaceflight that is under challenge.”

NASA hasn’t had “unrivaled primacy” since July 2011, when the last Shuttle flew.

That ship has sailed.

@Bill

In the age of e-books and print on demand, very few books go out of print anymore. That’s why a lot of books which have been out of print for years, if not decades, are available again, because e-books and print on demand makes it feasible to reissue those books and keep them in print.

@Cora Buhlert

I’m not sure this is true. I looked at an issue of Publisher’s Weekly from Mar 1996 (25 years ago) and checked a number of books advertised in it. Less than half were currently available as Ebooks or otherwise still in print (all are available on the second hand market, though).

But even old books recently brought back into “print” via ebooks represent “long-tail” sales. Books generate most of their income for authors via the initial advance, and then from sales immediately after publication. Backlist sales are not significant — OGH has linked a number of articles over the years that support this. When registration and renewal was required to keep copyrights, the vast majority (>80%; I wish I could locate the study for link) were not renewed, because they were commercially exhausted. Very few copyrighted works generate significant income a generation after their release; the law should reflect this, rather than act as if the economics of Sherlock Holmes is typical.

@bill – Why would you look to a pre-ebook year to evaluate post-ebook reality?

Makes no sense.

Because I wanted to make the point that there are many relatively recent books that aren’t available as ebooks.

But if it’s important that the books be current, here’s an example. My main hobby is conjuring/sleight of hand. The big magazine in the field is Genii. They’ve reviewed 9 books in the first three issues of 2021. Only one of them is available as an Ebook.

My personal opinion is that I am OK with one of “N years from creation” (N somewhere in the region of 25 to 125 years) OR “life + M years” (m somewhere in the 15 to 50 years region) for individually-owned copyright and J years non-renewable for corporation-owned copyright (J being ideally 25, but I could be argued into anything up to 50).