By John Hertz: (reprinted, mostly, from No Direction Home 29) Also reaching a centenary this year is Felix the Cat, who arrived with The Adventures of Felix or, if as sometimes considered he continued Master Tom introduced earlier, Feline Follies (each 1919). He came from the studio of Pat Sullivan, created by Sullivan (1885-1933), Sullivan’s lead animator Otto Messmer (1892-1983), or both, the first animated-cartoon character to win international fame. In 1921 Winslow B. Felix (1890-1936), a friend of Sullivan’s, opened a Chevrolet automobile dealership in Los Angeles irresistibly called Felix Chevrolet; in 1958 new owner Nick Shammas (1915-2003) put up a giant Felix the Cat sign, still proudly maintained by the current owner, 3330 S. Figueroa St., Los Angeles 90007. Everyone knew Felix’ pacing deep in thought during the cartoons (at left, from Oceantics, 1930). There was also a comic strip for newspapers (1923-1966). The fantasy element was broader, or something, than anthropomorphism; at a moment when a man might tip his hat, Felix might raise an arc with his ears from the top of his head; wanting to see at a distance, he might take off his tail and look through it as a telescope. Later, at the hands of Joe Oriolo (1913-1985) for television, Felix had a satchel Bag of Tricks; this may have been a weakening, or even a blandification, but it produced an object which an opponent could try to get. Joe’s son Don (1946- ), a painter, musician, and maker of guitars, inherited Felix, became known as the Felix the Cat Guy, and licensed him in the United States and abroad, particularly in Japan; dozens of Felix paintings by Don have appeared, some with guitars, at least one noting the resemblance of Felix and the Kit-Cat® Klock (invented 1932 by Earl Arnault 1904-1971, adopting a distinctive bow tie in 1954, or pearls for the Lady Kit-Cat in 2001). In 2014 rights to Felix were acquired by DreamWorks Animation, now part of NBCUniversal owned in turn by Comcast.

By John Hertz: (reprinted, mostly, from No Direction Home 29) Also reaching a centenary this year is Felix the Cat, who arrived with The Adventures of Felix or, if as sometimes considered he continued Master Tom introduced earlier, Feline Follies (each 1919). He came from the studio of Pat Sullivan, created by Sullivan (1885-1933), Sullivan’s lead animator Otto Messmer (1892-1983), or both, the first animated-cartoon character to win international fame. In 1921 Winslow B. Felix (1890-1936), a friend of Sullivan’s, opened a Chevrolet automobile dealership in Los Angeles irresistibly called Felix Chevrolet; in 1958 new owner Nick Shammas (1915-2003) put up a giant Felix the Cat sign, still proudly maintained by the current owner, 3330 S. Figueroa St., Los Angeles 90007. Everyone knew Felix’ pacing deep in thought during the cartoons (at left, from Oceantics, 1930). There was also a comic strip for newspapers (1923-1966). The fantasy element was broader, or something, than anthropomorphism; at a moment when a man might tip his hat, Felix might raise an arc with his ears from the top of his head; wanting to see at a distance, he might take off his tail and look through it as a telescope. Later, at the hands of Joe Oriolo (1913-1985) for television, Felix had a satchel Bag of Tricks; this may have been a weakening, or even a blandification, but it produced an object which an opponent could try to get. Joe’s son Don (1946- ), a painter, musician, and maker of guitars, inherited Felix, became known as the Felix the Cat Guy, and licensed him in the United States and abroad, particularly in Japan; dozens of Felix paintings by Don have appeared, some with guitars, at least one noting the resemblance of Felix and the Kit-Cat® Klock (invented 1932 by Earl Arnault 1904-1971, adopting a distinctive bow tie in 1954, or pearls for the Lady Kit-Cat in 2001). In 2014 rights to Felix were acquired by DreamWorks Animation, now part of NBCUniversal owned in turn by Comcast.

In 1925, Felix at his height, Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) led a Vanity Fair article with him.

In the course of one of his adventures, my favorite dramatic hero, Felix the Cat, begins to sing…. little black notes hang in the air above him…. He reaches up, catches a few handfuls of them, and…. fit[s] them together into the most ingenious … scooter … the wheels … made out of the round heads of the notes, the framework of their tails. He helps his companion into her seat, climbs in himself, seizes by its barbs the semi-quaver which serves as the lever of propulsion and, working it vigorously backwards and forwards, shoots away…. What the cinema can do better than literature is to be fantastic…. A study of Felix the Cat would teach … many valuable lessons.

“Where Are the Movies Moving? The brilliant success of the cinema in portraying the fantastic and preposterous”; July, pp. 39, 78

Having spoken of a fictional black cat famous through graphics I must bring another, who started earlier, ended earlier, stayed mainly on the plain printed page (though there were 230 animations – half as many as Felix), was less widely known but perhaps greater: Krazy Kat, in the eponymous 1913-1944 comic strip by George Herriman (1880-1944). Fantasy element broader, or something, than anthropomorphism? The landscape is strange, and while the characters are stationary may change. Krazy has been called androgynous; sometimes she seems to be female, sometimes he seems to be male. The characterization, the layout, the language, the plot (if any) – is there anything that isn’t extraordinary? maybe the policeman, Officer Pupp? – no – maybe Ignatz Mouse’s bricks? yet if they are the anchor to reality, that is very strange. And William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951) loved it. P. McDonnell et al. eds., Krazy Kat (1986) is a good overview. Bill Blackbeard while at Eclipse reprinted the 1916-1924 Sunday strips in nine volumes 1988-1992, then at Fantagraphics the 1925-1944 Sundays in ten more volumes 2002-2008.

Having spoken of a fictional black cat famous through graphics I must bring another, who started earlier, ended earlier, stayed mainly on the plain printed page (though there were 230 animations – half as many as Felix), was less widely known but perhaps greater: Krazy Kat, in the eponymous 1913-1944 comic strip by George Herriman (1880-1944). Fantasy element broader, or something, than anthropomorphism? The landscape is strange, and while the characters are stationary may change. Krazy has been called androgynous; sometimes she seems to be female, sometimes he seems to be male. The characterization, the layout, the language, the plot (if any) – is there anything that isn’t extraordinary? maybe the policeman, Officer Pupp? – no – maybe Ignatz Mouse’s bricks? yet if they are the anchor to reality, that is very strange. And William Randolph Hearst (1863-1951) loved it. P. McDonnell et al. eds., Krazy Kat (1986) is a good overview. Bill Blackbeard while at Eclipse reprinted the 1916-1924 Sunday strips in nine volumes 1988-1992, then at Fantagraphics the 1925-1944 Sundays in ten more volumes 2002-2008.

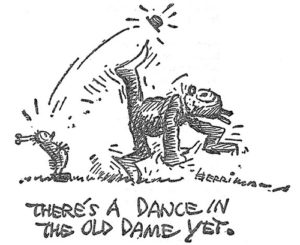

Because Herriman illustrated the tales of Archy and Mehitabel by Don Marquis (“MAR-kwiss”; 1878-1937) we know Mehitabel, an alley cat with whom Archy the cockroach hung out, was also black. Starting in 1916 Marquis ran them in his column for the New York City newspaper The Evening Sun, then in the Tribune, then in Collier’s magazine, then The Saturday Evening Post. Archy, the protagonist, had been a free-verse poet in an earlier life; he took to writing stories and poems on a typewriter in the newspaper office after everyone had left, climbing onto the machine and hurling himself onto one key at a time; he couldn’t manage capital letters, which called for simultaneously pressing the Shift key (though once landing on the Shift Lock key he wrote CAPITALS AT LAST). Several collections have been published; Herriman is in them only, starting about 1932. Michael Sims edited The Annotated Archy and Mehitabel in 2006.

Because Herriman illustrated the tales of Archy and Mehitabel by Don Marquis (“MAR-kwiss”; 1878-1937) we know Mehitabel, an alley cat with whom Archy the cockroach hung out, was also black. Starting in 1916 Marquis ran them in his column for the New York City newspaper The Evening Sun, then in the Tribune, then in Collier’s magazine, then The Saturday Evening Post. Archy, the protagonist, had been a free-verse poet in an earlier life; he took to writing stories and poems on a typewriter in the newspaper office after everyone had left, climbing onto the machine and hurling himself onto one key at a time; he couldn’t manage capital letters, which called for simultaneously pressing the Shift key (though once landing on the Shift Lock key he wrote CAPITALS AT LAST). Several collections have been published; Herriman is in them only, starting about 1932. Michael Sims edited The Annotated Archy and Mehitabel in 2006.

Filers know a long run of photographs from people under the topic “Cats Sleep on Science Fiction”. Last September I sent a photo I took at the 2018 World Science Fiction Convention of Steven Barnes asleep on some SF he was writing. He was, I explained, one of the coolest cats I knew. Note that Our Gracious Host uses the spelling “SFF”, presumably to make certain-sure, in these days of uncertainty, that both science fiction and fantasy are included.

The KitKat candy bar, wafers coated in chocolate, was originally made in England by Rowntree’s of York; now by Hershey in the United States, by Nestlé elsewhere. When I went to Yokohama for the 2007 Worldcon (“The Worldcon I Saw”, File 770 152 [PDF]; “The Residence of the Wind”, Argentus 8 [PDF]), Terry Karney said I should be sure to try a green-tea KitKat, because they were strange. He was right. I had been brought from the U.S. by the Hertz Across to Nippon Alliance (hana meaning flower or blossom is a Japanese word much used in poetry), Chris O’Shea from the United Kingdom by the Japanese Expeditionary Travel Scholarship (JETS).

As I was going my way west

Farther than ever one day,

I met a traveler going east.

The world is round, they say.

Title, Felix Mendelssohn and His Times p. 1 (H. Jacob, 1963; J.L.F. Mendelssohn-Bartholdy 1809-1847); felix in Latin means happy or fortunate, felicissimus is the superlative; fortunate lingers in English happy (which is mostly cheerful, contented, sunny), since hap is occur, and English still has happen, still allows e.g. “He had the happy knack of bringing people to like him”.