By Steve Vertlieb: I’ve read with interest some of the recent discussions concerning the measure of Hugo Friedhofer’s importance as a composer, and it set my memory sailing back to another time in a musical galaxy long ago and far away. I have always considered Maestro Friedhofer among the most important, if underrated, composers of Hollywood’s golden era. His contributions to this lyrical art form have placed him high above most contemporary artists and musicians in my estimation and he will, perhaps, live on as one of the unsung immortals of film scoring.

I recall conversations with Miklos Rozsa regarding Friedhofer’s contribution to motion picture music forty-five years ago. Rozsa found Hugo Friedhofer an enormously gifted composer who had contributed more to the world of music than he would ever know. Indeed, Friedhofer’s assessment of his own accomplishments was, to put it bluntly, derogatory and self-punishing. Whenever the two spoke on the matter, Friedhofer would ridicule his own achievements and describe his career as miniscule and inadequate.

Friedhofer, as Rozsa discovered, lambasted the studio system and ridiculed his own significance within the industry. He had serious issues concerning his own self-worth, and grew increasingly morose and cynical. He turned ever frequently to alcohol as a temporary cure for his depression and, during these bouts with feelings of inadequacy, became sadly impossible to reach. Rozsa told me that he had often tried to bolster Friedhofer’s sense of worth by commiserating with him, and reminding him of his many successes but that Friedhofer simply refused to accept his value and importance as an artist. Finally, it grew too painful to broach the subject. If Friedhofer felt more comfortable in his escalating self-flagellation, there was little that Rozsa could do to lift him out of it. He couldn’t allow his own positive attitude to be pulled down by someone who could only continue to wallow in self-pity and emotional suicide.

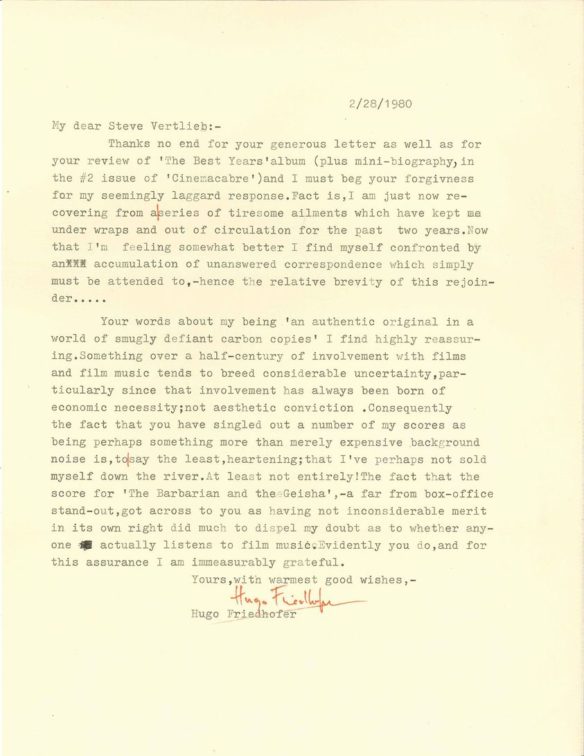

A year later, I decided to try to track Friedhofer down and attempt to repay the gift of beauty he had bestowed upon my life. I found his address and wrote him a long, loving letter of genuine admiration for his work and artistry. In late February, 1980, I received a reply written on an old, rickety typewriter. The page appeared stained with tears. The letter remains one of the most treasured pieces of correspondence that I’ve ever received. If I may, I’d like to share it with you.

2/28/1980

My Dear Steve Vertlieb:-

Thanks no end for your generous letter as well as for your review of ‘The Best Years’ album (plus mini-biography, in the #2 issue of Cinemacabre’) and I must beg your forgiveness for my seemingly laggard response. Fact is, I am just now recovering from a series of tiresome ailments which have kept me under wraps and out of circulation for the past two years. Now that I’m feeling somewhat better I find myself confronted by an accumulation of unanswered correspondence which simply must be attended to,-hence the relative brevity of this rejoinder…..

Your words about my being ‘an authentic original in a world of smugly defiant carbon copies’ I find highly reassuring. Something over a half-century of involvement with films and film music tends to breed considerable uncertainty, particularly since that involvement has always been born of economic necessity;not aesthetic conviction. Consequently, the fact that you have singled out a number of my scores as being perhaps something more than merely expensive background noise is, to say the least, heartening; that I’ve perhaps not sold myself down the river. At least not entirely. The fact that the score for ‘The Barbarian and the Geisha’,- a far from box-office stand-out, got across to you as having not inconsiderable merit in its own right did much to dispel my doubt as to whether anyone actually listens to film music. Evidently you do, and for this assurance I am immeasurably grateful.

Yours, with warmest good wishes,-

Hugo Friedhofer

The last time Miklos Rozsa had seen Hugo Friedhofer was in a small restaurant in Hollywood. Friedhofer was seated, alone, at a table in a darkened corner of the room. His head was bowed and resting within his arms. Before him was a drink, half consumed. As Friedhofer weakly lifted his head from the table, he saw Rozsa walking in. Rozsa waved. Friedhofer managed merely a feeble attempt at raising his own arm in response.

I think of the Oscar winning triumph and majestic beauty of his music for William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946). I hear the exquisite strains of his love themes for The Barbarian and the Geisha and Soldier of Fortune. I experience the rapturous joy of listening to his music for Boy On A Dolphin, and I am moved to tears by the gentle expression of a man’s inner depth and creativity. Would that HE might have seen the value and importance of his contribution to this wondrous and magical art form while he lived.

A little more than a year after I received his letter, Hugh Friedhofer suffered complications from a fall and passed away. His incomparable gift to the world of film and film music will, I believe, endure and flourish for many joyous years to come.