(1) SELLING FANTASY. [Item by Andrew (Not Werdna).] “Lester del Rey invented the fantasy genre in book publishing” alleges Slate’s Dan Sinykin.

Lester del Rey wore 1950s-style horn-rimmed glasses, an unruly billy-goat beard, and his silver hair brushed back above a big forehead. He liberally dispensed cards that said: Lester del Rey, Expert. He sometimes said his full name was Ramón Felipe San Juan Mario Silvio Enrico Smith Heathcourt-Brace Sierra y Alvarez-del Rey y de los Verdes. He was in fact born Leonard Knapp, son of Wright Knapp, in 1915 in rural southeastern Minnesota, subject to the Minnesotan fever—Jay Gatz, Prince Rogers Nelson, Robert Zimmerman—for reinventing oneself. In 1977, del Rey, then in his 60s, turned his proclivity for fabulism to profit: He invented fantasy fiction as we know it….

(2) PAYING OUR RESPECTS. Condolences to Cora Buhlert whose father passed away today.

(3) JUMP ON THE BANNED WAGON. “Banned Books Week: PRH’s ‘Banned Wagon’ Hits the Road” – Publishing Perspectives has the story. Banned Books Week is October 1-7. The tour schedule is at the link. The dozen showcased books include two genre works, The Handmaid’s Tale and Too Bright to See.

The arrival of this year’s Banned Books Week—led by one of the most comprehensive coalitions of free-expression organizations in the business–is themed Let Freedom Read. Engaged in the effort are the American Library Association, Amnesty International USA, the Authors Guild, the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund, the National Book Foundation, PEN America, and the Center for the Book at the Library of Congress, among others.

Hearing the call, Penguin Random House–the world’s largest and most internationally positioned of trade publishers– is gassing up something new: its “Banned Wagon: A Vehicle for Change.”

The goal is to take the debate right into the American South during Banned Books Week. Putting wheels on its “Read Banned Books” message, the vehicle not only will showcase a selection of 12 of the publisher’s frequently challenged books but will also distribute free copies of those books to attendees in each of the cities in which the tour makes a stop….

These are the 12 books published by Penguin Random House and being loaded into the Banned Wagon as it rolls through the American South during Banned Books Week.

- I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings by Maya Angelou

- The Handmaid’s Taleby Margaret Atwood

- Shout by Laurie Halse Anderson

- I Am Jazz by Jessica Herthel and Jazz Jennings

- The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini

- How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi

- The Magic Fish by Trung Le Nguyen

- Too Bright to See by Kyle Lukoff

- The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison

- Pride: The Story of Harvey Milk and the Rainbow Flag by Rob Sanders

- The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot

- Dear Martin by Nic Stone

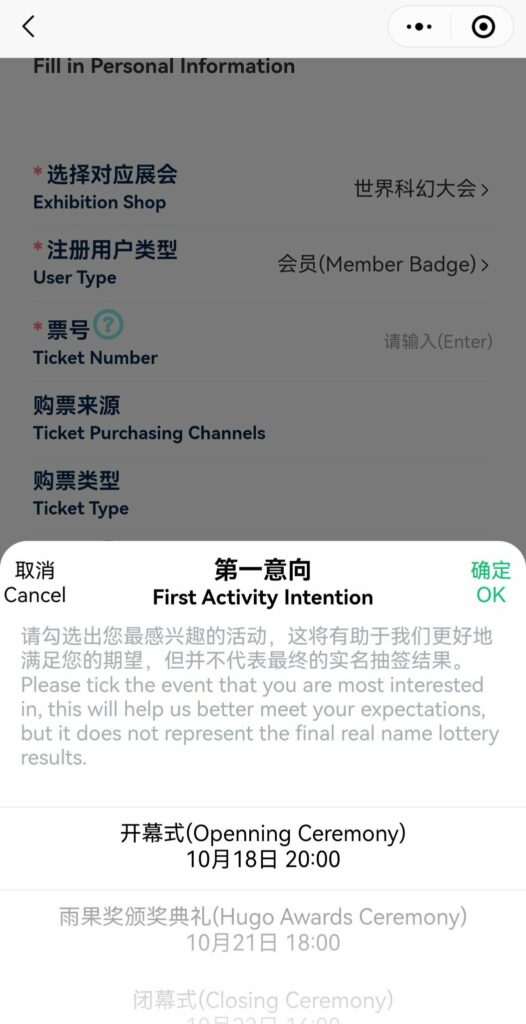

(4) CHENGDU WORLDCON ROUNDUP. [Item by Ersatz Culture.]

Chengdu Worldcon makes Chinese-language-only announcement about attending registration and participation rules

This has been published on the official Chinese-language site, WeChat and Weibo, but as of 19:00 BST, I haven’t seen any equivalent English language statement. As such this item is very dependent on machine translation, and could contain misunderstandings. However, the text has been run through Google Translate, DeepL and Vivaldi Lingvanex, with similar results output each time.

This is the Google Translate version of the main text of the page on the official site: https://www.chengduworldcon.com/Xnews/275.html

2023 Chengdu World Science Fiction Convention Membership Registration and Drawing Participation Rules for Three Major Ceremonies Released

Release time: 2023-10-01 12:42

Dear fantasy fans:

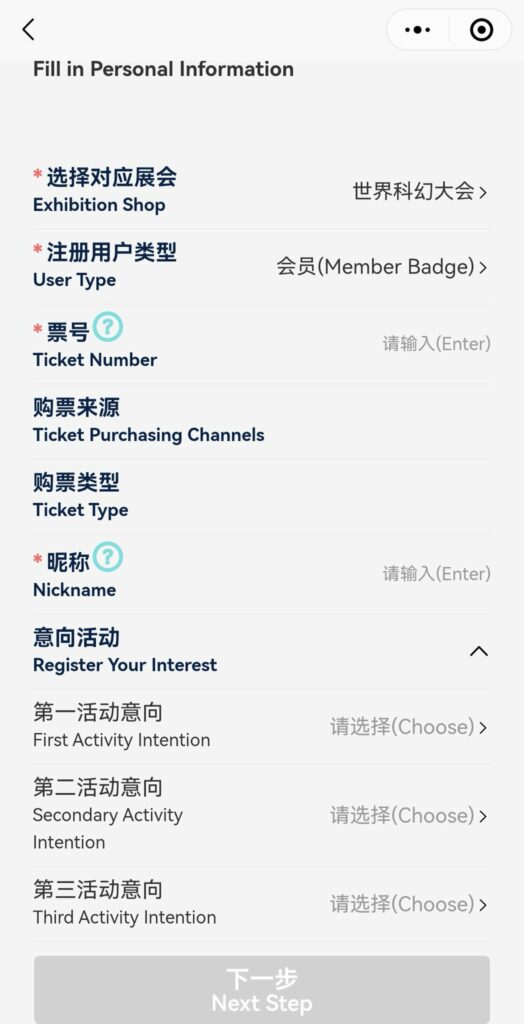

Thank you for your attention to the 2023 Chengdu World Science Fiction Conference. From now on, the WeChat applet for membership certificate registration (“Exhibition Hall Appointment”) is officially launched. Members who purchase offline conference passes need to register through the mini program [DeepL translates this as “app”] to obtain the QR code for the replacement certificate. The membership certificate [DeepL translates this as “membership ID”] exchanged with this code on site will be your only voucher [DeepL translates this as “credentials”] for entering the venue during the conference. Please log in and register in time.

In accordance with the convention [DeepL translates this as “usual practice”] of the World Science Fiction Convention, the opening ceremony, Hugo Award Ceremony and Closing Ceremony will have a maximum number of on-site spectators. This conference will confirm the offline participation pass members who will participate in the opening ceremony, Hugo Award ceremony and closing ceremony through online lottery in advance.

There’s a QR code which I presume links to the aforementioned WeChat applet, followed by details of the various rules and regulations; the bits that I thought noteworthy are:

- From now until 24:00 on October 9, members with offline participation passes can register for certification by searching the “Exhibition Hall Appointment” WeChat applet.

- The lottery will be sorted according to the information about the intended viewing activities filled in by each member, and will be notarized and implemented by the Shudu Notary Office in Chengdu, Sichuan Province. Each winning member can only participate in one grand ceremony. The winning results will be sent to the winning members via SMS in a timely manner.

- Starting from 15:00 on October 13, you can check the lottery results through the official website of the 2023 Chengdu World Science Fiction Conference and the “Exhibition Hall Appointment” WeChat applet.

- The results of this lottery will not affect participation in other activities such as on-site theme salons and theme exhibitions. The relevant schedule of the theme salon and theme exhibition will be announced soon, so stay tuned.

- The right to interpret these rules belongs to the 2023 Chengdu World Science Fiction Convention Organizing Committee

The QQ link is: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/EFcTsNCg0pyt2qbTxVPzJg. The Weibo link is: https://weibo.com/7634468344/NlPaCz8yw (which has received 52 comments as I write this up)

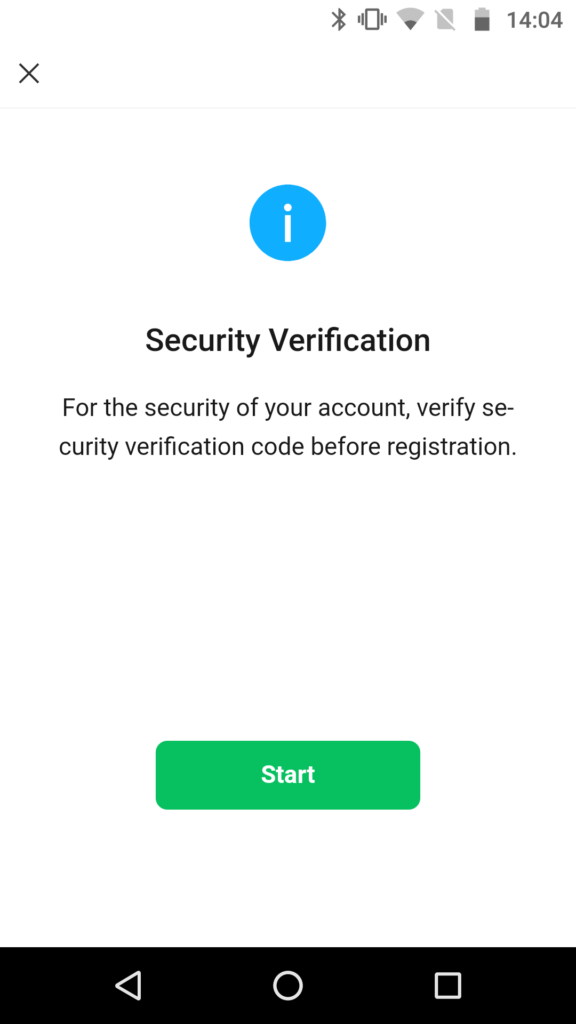

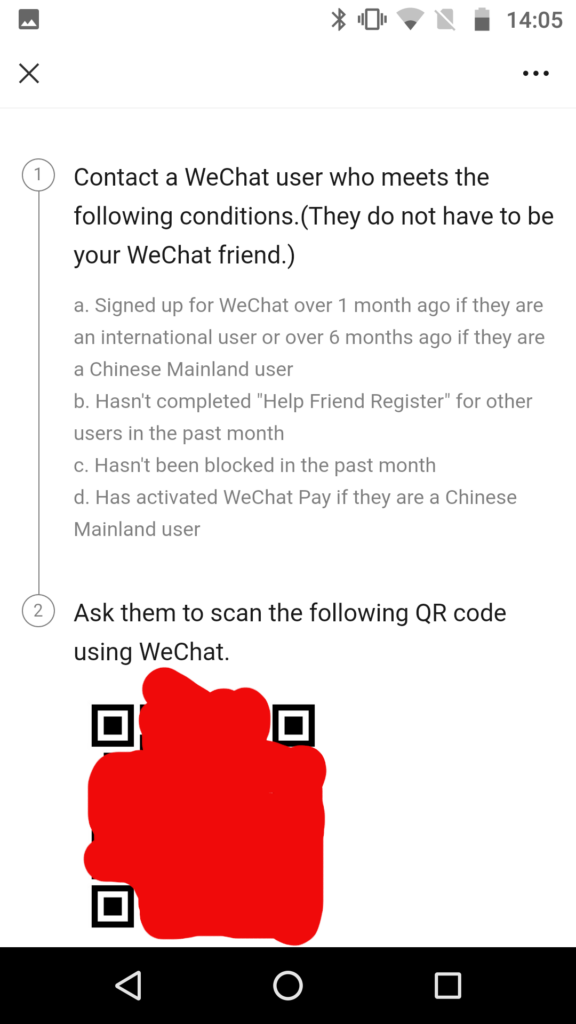

Assuming that my interpretation of this is correct, in that it’s necessary to install the WeChat app on your phone to be able to even get into the con venue, it should be pointed out that concerns have been raised about the security and privacy aspects of that app: https://foundation.mozilla.org/en/privacynotincluded/wechat/ (2001)

I’d previously installed this app on an old unused Android phone (using a test Google account,) and I suspect that many foreign users will struggle to register a WeChat account, as it requires an existing user to verify you via a QR code:

1. Contact a WeChat user who meets the following conditions. (They do not have to be your

WeChat friend.)a. Signed up for WeChat over 1 month ago if they are an international user or over 6

months ago if they are a Chinese Mainland user

b. Hasn’t completed “Help Friend Register” for other users in the past month

c. Hasn’t been blocked in the past month

d. Has activated WeChat Pay if they are a Chinese Mainland user

2. Ask them to scan the following QR code using WeChat.

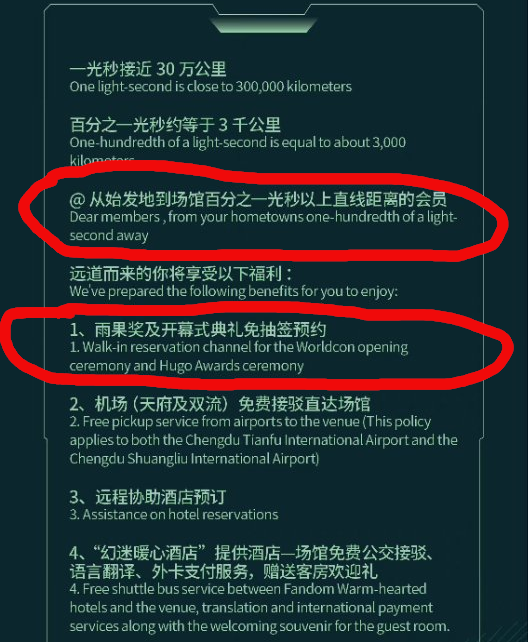

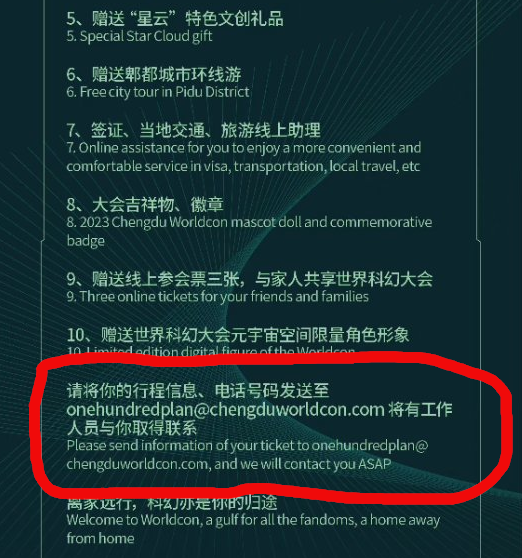

It has since been pointed out to me that the previously announced “100th Light-second Plan” covers some of this (maybe)? That indicated that if attendees email the provided address, they will gain access to a “reservation channel” for the opening and Hugo ceremonies.

This doesn’t directly address the implication in today’s announcement that you need WeChat to enter the con venue – and I note that it only talks about the opening and Hugo ceremonies, not the closing ceremony – but maybe this hints that this has already been thought about? On the other hand, I must confess I’m more than a bit uncomfortable at the idea that foreigners get privileged access to some of the main events, but locals have to take their chances in a lottery.

For reference, here are a couple of screenshots I was sent of what the WeChat app registration looks like.

(5) WHO SPEAKS FOR THE TREES? Alyssa Hall considers “’The Long Defeat’: Reading Tolkien in the Time of Climate Change” at Tor.com.

Allegorical readings of The Lord of the Rings vexed Tolkien. In the Foreword to the second edition of the books, he wrote of his distaste for allegory altogether: “I much prefer history, true or feigned.” The environmentalism that’s evident throughout his chronicles of Middle-earth, from the rebellion of Fangorn Forest to the Scouring of the Shire to the destruction of the Two Trees of Valinor? That was all based in history and autobiography, from a childhood in which “the country in which I lived was being shabbily destroyed before I was ten,” only made mythic.

Before I was ten, the third in a series of international scientific reports on our warming Earth was published, and the Kyoto Protocol set targets for countries to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. Prior to those developments, Svante Arrhenius had connected the burning of coal to rising carbon dioxide levels and hotter climates; John Tyndall had identified the gases responsible for the greenhouse effect; and Eunice Foote had realized that carbon dioxide gas could trap heat from the sun. In fact, Arrhenius did his work long before I was born, near the beginning of Tolkien’s own lifetime; Tyndall and Foote, before Tolkien was born.

When it comes to what is true and what has been feigned, the historicity of climate change is an established fact, and the willful denial of its reality is a toxic fiction. Climate change was already occurring during the years when Tolkien lived and wrote. Though he may not have been aware of a growing knowledge of global warming, I think his work is directly applicable to all of us who face the current onslaught of frightening headlines about climate disasters and think, like Frodo, “I wish it need not have happened in my time.” Tolkien, if not a professed environmentalist, was certainly a pastoralist, a lover of trees and countryside and an opposer of polluting industrialization. Ents, Eagles, Beornings, and other forms of nature personified fill his work, as do plot points and revelations that hinge on the destruction of one or more trees (or Trees). His letters put it even more plainly: “The savage sound of an electric saw is never silent wherever trees are still found growing.” Climate change is industrial deforestation writ large. For me, there’s no author who gives the natural world its due the way Tolkien does.

With Amazon’s The Rings of Power series driving a new pop-cultural wave of interest in Middle-earth at the same time global temperatures are shattering records and driving extreme weather events around the world, I’ve found myself longing for Tolkien or a Tolkien-like voice of the twentieth-first century: Someone pouring out words about the living world, writing that emerges from unabashed, earnest love for nature. The mounting threat of climate change has me returning to my childhood favorites to seek wisdom for these long defeats in this Century of Disasters, to look for a light forward in dark times for the planet and its inhabitants….

(6) RECORD SETTING RESENTMENT. The Guardian lists the “Top 10 grudge holders in fiction”. No. 4 in the list is —

The Employees: A Workplace Novel of the 22nd Century by Olga Ravn, translated by Martin Aitken

“Ravn’s novel is set on the Six-Thousand Ship, which is orbiting a faraway planet New Discovery, where the crew has discovered a number of strange objects. The book is structured around a series of recorded statements, of varied degrees of redaction and fullness, made by the ship’s human and humanoid crew to some kind of committee about the effects of these objects upon themselves. The objects have the effect of defamiliarising the workplace for the crew, making them see it anew, making them realise their lives might have meaning beyond work. Over the course of the book, their resentment against their employers grows and grows.”

Several others are genre by virtue of being ghost stories of one kind or another.

(7) SERIES KILLER. Hugo voting closed yesterday. Nicholas Whyte has something he’d like to say: “2023 Hugos: Best Series – why I voted No Award” at From the Heart of Europe.

I voted No Award for this year’s Hugo Award for Best Series. I think the category is a bad idea in principle which is now showing its limitations in practice. My objections are as follows:

- The Hugos ought to celebrate the best activity of the previous year, and only the previous year. For some of the other categories (Semiprozine, Fanzine, Fancast), earlier work is taken into account to determine eligibility, but the award is clearly for achievements of the previous calendar year. Best Series is inevitably an award for a multi-year set of activities.

- It is impossible for the diligent reader to read all of the work nominated for Best Series in a given year. By giving the award we are deliberately engineering a situation where voters cast their votes based on imperfect knowledge of the finalists.

- We are now seeing repeat nominations for series that have been unsuccessful finalists before. I feel sympathy for authors who must feel that they are waiting for their turn, but that’s not the way an awards system should run…

More analysis, and how he ranked the finalists, at the link.

(8) FREE READ. Sunday Morning Transport encourages subscriptions with this story by John Chu, “Halfway Between Albany and West Point”.

October kicks off with John Chu’s thrilling vision of academia and his spectacularly embattled graduate student.

(9) TANKS FOR THE MEMORIES. “Toxic Avenger Remake Trailer: First Look at Peter Dinklage Film” – Gizmodo provides a gloss and a warning.

…Directed by Macon Blair, this new Toxic Avenger stars Game of Thrones fan favorite Peter Dinklage as Winston, a widower struggling to raise a stepson played by Jacob Tremblay. When his job, run by an evil corporate ass played by Kevin Bacon, won’t pay for health insurance, Winston fights back and ends up in a vat of toxic waste. Now, you don’t see really any of that in this first teaser (note that it’s very much NSFW!), but take that story and put it in this world, and you begin to get the idea of what this movie is….

(10) TODAY’S BIRTHDAYS.

[Compiled by Cat Eldridge.]

- Born October 1, 1914 — Donald Wollheim, 1914 – 1990. Created DAW Books. NolaCon II (1988) guest of honor. Founding member of the Futurians, Wollheim organized what was later deemed the first American science fiction convention, when a group from New York met with a group from Philadelphia on October 22, 1936 in Philadelphia. As an editor, he published Le Guin’s first two novels as an Ace Double. And would someone please explain to me how he published an unauthorized paperback edition of The Lord of the Rings? (Died 1990.)

- Born October 1, 1930 — Richard Harris. One of the Dumbledores in the Potter film franchise. He also played King Arthur in Camelot, Richard the Lion Hearted in Robin and Marian, Gulliver in Gulliver’s Travels, James Parker in Tarzan, the Ape Man and he voiced Opal in Kaena: The Prophecy. His acting in Tarzan, the Ape Man him a nominee for the Golden Raspberry Award for Worst Actor. Anyone seen that film? And why it got him that nomination? I saw the film a long time ago but don’t it clearly enough to say why this is so. (Died 2002.)

- Born October 1, 1935 — Dame Julie Andrews, DBE, 88. Mary Poppins! I could stop there but I won’t. (Hee.) She had a scene cut in which was a maid in The Return of the Pink Panther, and she’s uncredited as the singing voice of Ainsley Jarvis in The Pink Panther Strikes Again. Yet again she’s uncredited in a Panther film, this time as chairwoman in Trail of the Pink Panther. She voices Queen Lillian in Sherk 2, Shrek the Third and Shrek Forever After. And she’s the voice of Karathen in Aquaman.

- Born October 1, 1943 — Sharon Jarvis, 80. Did I ever tell you that aliases give me a mild headache? Well, they do. She did a splendid trilogy of somewhat erotic planetary adventures called These Lawless Worlds that Ellen Kozak co-wrote. She wrote two more series, charitably called pulp, one as Johanna Hailey and another as Kathleen Buckley. Now more interestingly to me, she was an editor in the early day, Seventies and Eighties. I’m going to quote at length from her website: “Sharon Jarvis has worked in the print media for more than twenty-five years for newspaper, magazine and in publishing companies. She has built a reputation for her market-wise expertise in the cutthroat world of publishing. Ms. Jarvis has been a sought-after editor from her days at Ballantine where she helped promote the billion-dollar science fiction boom. At Doubleday she was the acquisitions editor and worked with some of the biggest names in science fiction, including Isaac Asimov, Marion Zimmer Bradley and Harlan Ellison. At Playboy Press, Ms. Jarvis developed, instituted and promoted the science fiction line which helped sustain the publisher through many a setback in other general lines.”

- Born October 1, 1944 — Rick Katze, 79. A Boston fan and member of NESFA and MCFI. He’s chaired three Boskones, and worked many Worldcons. Quoting Fancyclopedia 3: “A lawyer professionally, he was counsel to the Connie Bailout Committee and negotiated the purchase of Connie’s [1983 Worldcon’s] unpaid non-fannish debt at about sixty cents on the dollar.” He’s an active editor for the NESFA Press, including the six-volume Best of Poul Anderson series.

- Born October 1, 1948 — Michael Ashley, 75. Way, way too prolific to cover in any detail so I’ll single out a few of his endeavors. The first, his magnificent The History of the Science Fiction Magazine, 1926 – 1965; the second being the companion series, The Time Machines: The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the Beginning to 1990. This not to slight anything else he has done such as The Gernsback Days: A Study in the Evolution of Modern Science Fiction from 1911 to 1936.

- Born October 1, 1964 — John Ridley, 59. Author of Those Who Walk in Darkness and What Fire Cannot Burn novels. Both excellent though high on the violence cringe scale. Writer on the Static Shock and Justice League series. Writer, The Authority: human on the inside graphic novel. And apparently the writer for Team Knight Rider, a female version of Knight Rider that would last one season in the Nineties.

- Born October 1, 1989 — Brie Larson, 34. Captain Marvel in the Marvel film universe. She’s also been in Kong: Skull Island as Mason Weaver, and plays Kit in the Unicorn Store which she also directed and produced. Her first genre role was Rachael in the “Into the Fire” of Touched by an Angel series; she also appeared as Krista Eisenburg in the “Slam” episode of Ghost Whisperer. She’s in The Marvels, scheduled out next month.

(11) COMICS SECTION.

- Tom Gauld has a sneak peek at a celebrity bio.

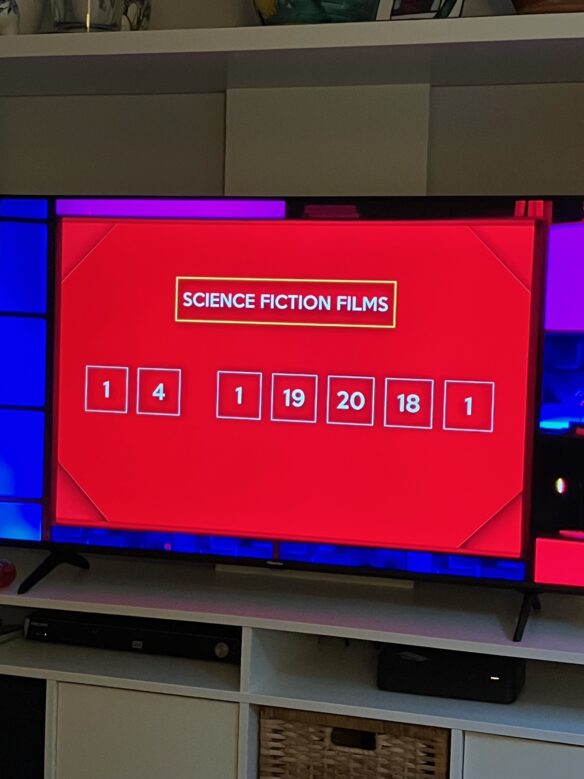

(12) SCIFI IN HOUSE OF GAMES. [Item by Steven French.] During the week BBC2 runs a nightly half-hour quiz show called House of Games in which each round features a different kind of puzzle and not even the host (Richard Osman, now perhaps even more well known as a crime writer) knows what kind is coming up next.

Watching a repeat from last year I noticed that one round featured science fiction movies whose titles were given in code; e.g.:

1 4 1 19 20 18 1

which one of the contestants got pretty quickly even though she’d never seen or even heard of the film!

(13) MORE THAN A SNOWBALL FIGHT. “What would happen if Russia invaded Finland? I went to a giant war game in London to find out” — the Guardian’s Tom Lamont brings back the story.

… It is 10am. Banks asks everyone present to imagine they are on the threshold of geopolitical catastrophe, somewhere a little beyond, though not that far beyond, our current perilous state. He fleshes out a scenario. Prolonged and humbling conflict in Ukraine as well as Finland’s recent accession to Nato has tested Russian pride to breaking point. Worsening matters, Nato has decided to press its advantage in the region by staging a military exercise on the Finnish-Russian border. China, Iran and India have made it plain: they’re not impressed by Nato. The Swedes are jangly, too. Spy planes, satellites and troop carriers are in play. A few wrong moves and all this posturing and provocation could ignite into something far worse. It is up to the players assembled in Bush House to try to war-game us back from the brink.

Now Banks moves among the crowd, handing out jobs like sweets. During this phase of a game, a real-life general might get a tap on the shoulder and tumble to become a low-level functionary for the first time in decades. A career shit-eater might get to feed somebody else the shit. (Maybe the general.) Anyone – a data specialist, a science nerd, an archive-dwelling academic – might find themselves near-omnipotent for the day. With a pointed finger, Banks elevates four random people to play as Russian high command. In a corner of one of the conference rooms, put aside for their exclusive use, the four newly minted Russians are told they can organise themselves and their decision-making however they want. “If you want to be equals here, that’s fine,” says one of Banks’s PhD students. “Or if you want to appoint a dictator, that’s fine, too.”…

(14) A DIFFERENT CHORD. “Queen guitarist Brian May helps NASA return asteroid sample to Earth” at USA Today.

When he’s not rocking out on stage as a founding member of Queen, Brian May enjoys a healthy scientific interest in outer space.

But it’s no mere hobby for the 76-year-old guitar legend to gaze upon the stars or research the nature of the universe. May, an accomplished scientist who has a doctorate in astrophysics, recently helped NASA return its first ever asteroid sample to Earth.

The sample consisting of rocks and dust was obtained from the asteroid Bennu and arrived Sunday back in Earth’s orbit. May was an integral part of the mission, creating stereoscopic images that allowed the mission’s leader and team to find a safe landing spot on the asteroid, which has the potential to crash into Earth sometime in the future…

(15) WHEN THINGS GO BUMP IN THE NIGHT. The New York Times discusses a hypothesis: “Saturn’s Rings May Have Formed in a Surprisingly Recent Crash of 2 Moons”.

Try to imagine Saturn without its signature rings. Now picture two large icy moons shifting closer together little by little until — boom. Chaos. What was solid is now fluid. Diamantine shards scatter into the darkness. Many icy fragments tumble close to Saturn, remain there and dance around the gas giant in unison, ultimately forging the heavyweight body’s exquisite discs.

This spectacular scene comes from an attempt to answer one of the greatest mysteries of the solar system: Where did Saturn’s rings come from, and when did they form?

A study, published this week in The Astrophysical Journal, leans into the notion that they are not billions of years old, but were crafted in the recent astronomic past—perhaps by the collision of two modestly sized frost-flecked moons only a few hundred million years ago.

“I’m sure it would have been great to see if the dinosaurs had had a good enough telescope,” said Jacob Kegerreis, a research scientist at NASA’s Ames Research Center in Mountain View, Calif., and one of the study’s authors….

(16) DREAM HOMES. The New York Times speculates “Maybe in Your Lifetime, People Will Live on the Moon and Then Mars”. “Through partnerships and 3-D printing, NASA is plotting how to build houses on the moon by 2040.”

… NASA is now plotting a return. This time around, the stay will be long-term. To make it happen, NASA is going to build houses on the moon — ones that can be used not just by astronauts but ordinary civilians as well. They believe that by 2040, Americans will have their first subdivision in space. Living on Mars isn’t far behind. Some in the scientific community say NASA’s timeline is overly ambitious, particularly before a proven success with a new lunar landing. But seven NASA scientists interviewed for this article all said that a 2040 goal for lunar structures is attainable if the agency can continue to hit their benchmarks.

The U.S. space agency will blast a 3-D printer up to the moon and then build structures, layer by additive layer, out of a specialized lunar concrete created from the rock chips, mineral fragments and dust that sits on the top layer of the moon’s cratered surface and billows in poisonous clouds whenever disturbed — a moonshot of a plan made possible through new technology and partnerships with universities and private companies….

(17) VIDEO OF THE DAY. [Item by Danny Sichel.] Math counts as science. So this 14-minute animation by Alan Becker — which begins by providing simple visualizations of basic arithmetical concepts and quickly devolves into an all-out battle with lasers and giant mechs — is science fiction. “Animation vs. Math”.

[Thanks to SF Concatenation’s Jonathan Cowie, Mike Kennedy, Andrew Porter, Bill, Steven French, Danny Sichel, Jeff Smith, Andrew, (Not Werdna), Brown Robin, Ersatz Culture, John King Tarpinian, Chris Barkley, and Cat Eldridge for some of these stories. Title credit belongs to File 770 contributing editor of the day Soon Lee.]