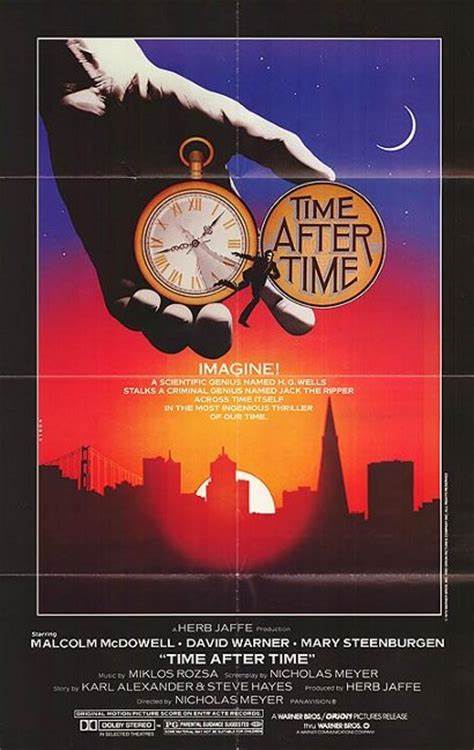

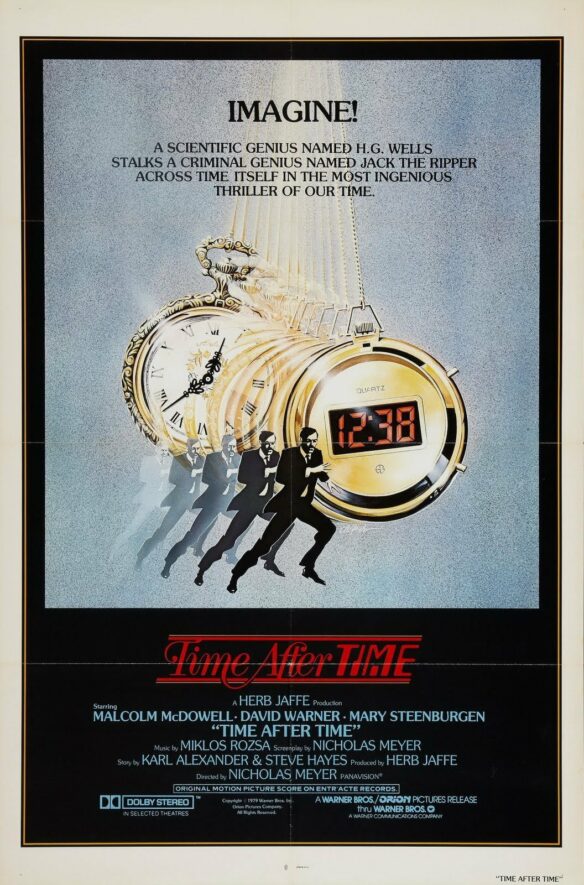

For the fortieth anniversary of Nicholas Meyer’s romantic fantasy masterpiece, released September 28th, 1979, here is a look back at the soundtrack release of the brilliant motion picture classic, Time After Time, and its legendary score by Miklos Rozsa.

The film, which suggested an entirely imaginary friendship between writer H.G. Wells and Jack The Ripper, follows the exploits of the famed science fiction author as he courageously chases the infamous murderer through time and space in a fabulous device of his own making.

His journey to prevent future bloodshed is the intoxicating premise of this sublime science fiction thriller for which three-time Oscar winning composer Miklos Rozsa fabricated one of his most exquisite romantic scores.

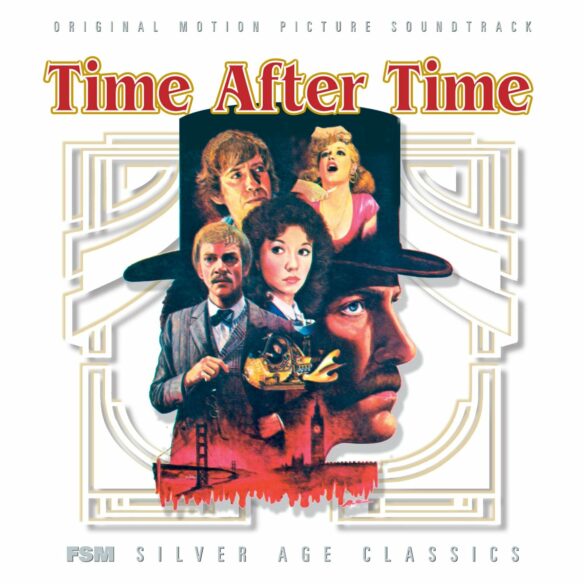

Produced by Lukas Kendall for his wonderful succession of soundtrack releases at Film Score Monthly, Rozsa’s inspired score is a musical journey worth taking … Time After Time.

By Steve Vertlieb: Toward the end of a summer cluttered with loud, virtually indistinguishable motion picture fare, a small cinematic miracle called Time After Time emerged quietly amidst the visual noise. Released by Warner Bros. on August 31, 1979, Nicholas Meyer’s tender fantasy was a ray of radiant sunshine spilling over a cloud covered, obediently commercial horizon. Based upon a novel by author Karl Alexander, from a story idea by Alexander along with Steven Hayes, the story found its inspiration unashamedly in the pages of Nicholas Meyer’s The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, in which a resurrected Sherlock Holmes battles his arch nemesis once more on paper and on film. Rather than pit the master detective against crime and punishment, however, Alexander decided to extract H.G. Wells from Victorian England and have him impersonate Holmes while trailing Jack the Ripper through portals of time. Nicholas Meyer, both flattered and intrigued by this updated tribute to his own work, decided that the novel might make an interesting film and, when approached by Karl Alexander, determined to option the novel with Warner Bros. for the screen rights.

Meyer wished to helm the picture himself and, as a novice director, wanted to fashion a retro sense about his introductory screen effort. He envisioned the traditional Max Steiner logo sequence opening the film, a concept that didn’t particularly excite Warner Bros, as the Forties intro hadn’t been used by the studio in years. He cast Malcolm McDowell as his hero, a courageous reversal of type casting since the actor had largely portrayed only villains and sleazy anti-heroes thus far in his career. It was an interesting choice, considering that Wells would be enacted as a sweet, innocent idealist with little worldly background or sophistication. For the music, Meyer wanted to have an old fashioned Hollywood score as the blanket caressing his lost protagonists. He chose one of his favorite composers, the legendary Miklos Rozsa, to create the magical score for his fantastic voyage.

Rozsa, for his part, was in the process of winding down his motion picture career and had been called upon only sporadically in the past twenty years by a film industry jaded, cynical, and blithely ignorant of its musical past. After winning his third and final Oscar for MGM’s 1959 epic Ben Hur, the composer found his talents ill used in a growing climate of slavish adoration to youthful demands, and insistence upon popular song score compilations. Except for a precious handful of worthwhile offers, such as Billy Wilder’s unforgettable The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes in 1970, Rozsa remained content to write music solely for the concert stage. All of that was about to change in 1975 with Jaws and, more importantly in 1977, with Star Wars and Close Encounters of the Third Kind. The rising popularity of composer John Williams, coupled with the spectacular sci-fi/fantasy epics of Steven Spielberg and George Lucas, had returned symphonic film music to its former glory. With increasing, renewed demand for dramatic, full blown orchestral scoring, both Williams and Jerry Goldsmith leaped to the forefront of a new musical renaissance in Hollywood. While each rose admirably to the occasion, neither composer had either the time or the opportunity to score every new film on the drawing boards. Out of respect for their remembered legacy, a daring handful of youthful directors reached back into time to utilize the talents of the few remaining composers from filmdom’s fabled golden age.

Time After Time was all the more remarkable for its Victorian sensibilities, and tender sensitivity in the midst of global narcissism, and cultural disdain. Both the screenplay, and its direction by Nicholas Meyer, seemed to embrace a painful longing for values long since replaced by worldly cynicism and ridicule. Vibrant in its infectious enthusiasm, the film seemed to hit a nerve with a small, yet influential segment of the film going population, quickly elevating the tiny “motion picture that could” to cult status and artistic reverie. Time After Time functioned comfortably on a variety of conceptual levels. It was an old-fashioned thriller in which author H.G. Wells, a Victorian novelist and unabashed idealist, chases the very personification of ancient evil through time, and the painful evolution of modern society.

It worked as a lovely comedy in which the now archaic Puritanism of nineteenth century England finds awkward reconciliation upon the mean streets of twentieth century San Francisco. It works equally well as pure storybook romanticism in which the handsome prince from another reality steals away the beleaguered heroine of a cruel and unforgiving kingdom, from which love and compassion have grown sublimated by callous cruelty, and emotional detachment.

For his part, composer Miklos Rozsa found comfort and creative reassurance in his own distinguished background and breeding, for Meyer’s cultural homage enveloped the world weary musician in a vaporous world that had long since vanished from experience. While only two film assignments remained in his future after completion of Nicholas Meyer’s romantic thriller, this haunting tale of poetic fate and synchronicity led Rozsa to compose a rich, brilliant score that has come to be regarded as a final masterwork by one of cinema’s most gifted artists. Rozsa’s music, like the cautionary loss of innocence articulated in Meyer’s fantasy, symbolizes a lush, passionate, deeply reflective longing for a world that has disappeared from the Earth that sired it. It is the bittersweet search for peace of mind and of heart that have gone with the wind, lost in the angry cynicism of societal maturity, and intellectual detachment. H.G. Wells has grown lost, a displaced “stranger in a strange land” trying to find home and, with its attainment, a return to simplicity and moral civility. Rozsa, himself adrift as a composer in a “brave new world” of noise and shallow contemplation, must have found a chord of artistic recollection and redemption within this sensitive visual remembrance, for his score is merely sublime.

The score for Time After Time has long been considered among the richest of Rozsa’s symphonic career. It is a dazzling musical tour de force, capturing every imaginative nuance of both character and characterization with complexity and radiant vitality. Rozsa paints his symphonic canvas with the expressive brush strokes of a great artist. He is a master of emotional interpretation, conveying each subtle nuance of character reflection and vulnerability in brilliant musical strokes and terminology. Whether illustrating thrilling chases through valleys and corridors of time or finding, in moments of quiet desperation, love’s passion lost and found, this cultural icon from cinema’s beginnings and roots, has invested ageless enthusiasm into a final portal of grace and cinematic eloquence.

The score for Meyer’s precious gem of a motion picture had been released on both album and compact disc in 1979 when Rozsa entered the studio one more time to re-record his music for Entr’acte Records. That excellent recording has stood well the proverbial test of time for the past thirty years. In an age, however, of archival restoration, Lukas Kendall and his brave army of preservationists have returned this brilliant score to its original stereophonic splendor with their spectacular release of the complete, original soundtrack on their Film Score Monthly label. Co-produced and issued through Craig Spaulding and his exhaustive Screen Archives Entertainment resource, the magnificent music for this timeless enterprise has now come full circle with a new and definitive representation of a glorious score. With the participation of Nicholas Meyer, original orchestrations by the late Christopher Palmer, and a handsome accompanying booklet with both literate and informative liner notes by Jeff Bond and Frank DeWald, this spectacular production is a joy to hear and to behold.

In its final moments, as Wells and Amy Catherine Robbins reach out their hands to one another, lonely souls conjoined across a sea of time and space, the sheer poetic grace of Meyer’s and Alexander’s tender science fiction fantasy reaches romantic crescendo. The heartbreaking passion of Rozsa’s orchestral rhapsody finds the summit of its power in the final chords of a brilliant career. Miklos Rozsa found his voice once more, as he had on so many occasions during a life in film spanning forty-five years…as he had done Time After Time.