By Daniel Dern: I’m not sure this is, for the most part, so much a “review” of Robert Heinlein’s The Pursuit of the Pankera: A Parallel Novel About Parallel Universes as opposed to a bunch of statements about it. Your space-time mileage may vary. Although since one goal is to help you decide whether or not you want to read the book, I guess that makes it a review.

(If you want a review that actually talks about the contents, here’s Sourdough Jackson’s scroll from back in May 2020.)

I grew up on the Heinlein juveniles, notably Have Space Suit, Will Travel, Citizen Of The Galaxy, The Star Beast and The Rolling Stones, and have read (or done my best to read) all Heinlein, including the essays, the alternate versions (more on this below), and including The Number Of The Beast. Some Heinlein, I still re-read; other, not so much.

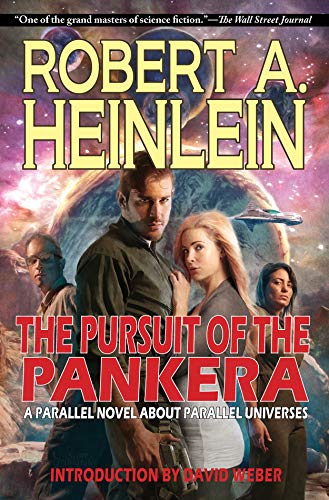

The Pursuit Of The Pankera is, according to the brief (half-page) Publisher’s note from Shahid Mahmud, Heinlein’s original, hitherto-unpublished novel whose first third he forked into his The Number Of The Beast. According to Mahmud’s note, “…[this] new book is one hundred percent Heinlein. Other than regular editorial work was asked to provide ‘fillers.'”

(Unlike, say, Variable Star, which Spider Robinson wrote based on Heinlein’s outline and notes.)

Number, according to Alan Brown’s “Long-Lost Treasure” article on Tor.com, “first appeared in portions serialized in OMNI magazine in 1978 under the editorial direction of Ben Bova….The book version of Heinlein’s novel was published in 1980.”

Now, we have the option (I’m not sure if it qualified as an “opportunity”) to read what Heinlein wrote originally.

The forking occurs in both books in Chapter 18, “right after the characters’ specially equipped car, the Gay Deceiver, makes its first jump to a parallel universe,” according to the Publisher’s Note (which appears also, with a slightly different first paragraph, in the new hardcover of Number, according to Amazon’s view.

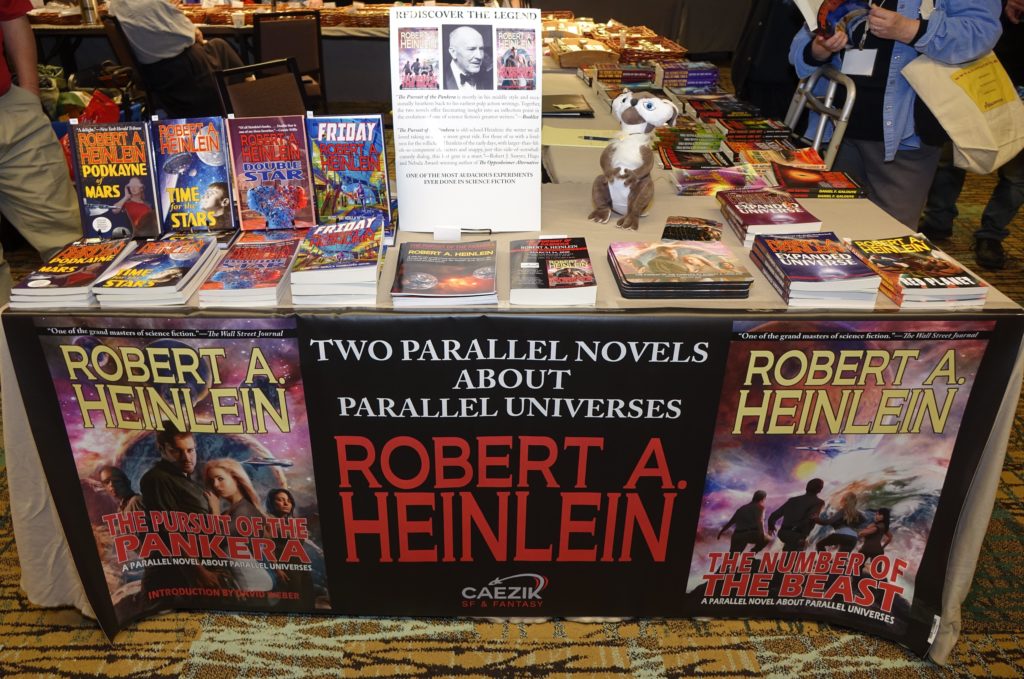

Pankera is not being promoted as an alternative version of Number, but rather, together they are identified/promoted as “two parallel novels about parallel universes.”

Arguably, that’s geometrically incorrect, the two books don’t parallel so much as fork (although they do semi-unfork a few times).

The “divergence in texts” is flagged by a small marker. In the hardcover of Pankera (via my library), it’s on page 152.

At Boskone 57, there was a free chapter sales promo, which began either at that point, or at the next chapter, which is like half a dozen pages later.

Based on the free chapter sampler of Pankera (I don’t remember whether it started at the demarc, or at the start of the next chapter) that I got at Boskone 57 back in February 2020 (just before Almost Everything Shut Down), I was sufficiently unenthused that I planned to not library-get the book when it became available.

Then, mid-late summer, seeing that the book was now available, and Things Being Different, I added it to my library reserve request list, and, a month or so later, with inter-library loan transit back in action, my place in line came up.

Most of the text and plot of Pankera goes in different directions and routes from Number, although the chapters/sections involving Oz and Charles Dodgson seem largely the same in both (and, not owning a copy of Number to check against, I’m not going to worry about it. It feels like I can recall some minor differences, no big deal). On the other hand, the Lensmen sections are significantly different. (See Sourdough’s review for deets.)

Pankera does NOT go places where Number did; in particular, (SEMI-SPOILER ALERT), it doesn’t go into the LazarusLongiverse. Other than our not getting to see Gay Deceiver and Dora schmooze (to which Lazarus Long apologizes to our protagonists, with something like “I’m sorry, my spaceship is corrupting your spaceship.”), given where Heinlein took this in Number, I consider this not-going-there a Good Thing. If you read Number and haven’t blanked that portion out from your memory, you know what I’m talking about, ’nuff not said.

On the more general subject of Heinlein “lost versions” — longer versions he wrote which he cut down for publication — I have mixed feelings, based on the ones I own/have read (thanks largely to Baen Books). The longer version of Red Planet had a lot of interesting stuff in it, and, IIRC, more depth. The longer version of The Puppet Masters felt weaker, in writing punch. Podkayne — mostly, IIRC, Heinlein’s original ending, and, in my paperback, with sundry essays and other bonus stuff, was interesting and made sense. Stranger In A Strange Land did not feel improved by the restored text throughout. (Did I miss any? That’s all I can recall.) But Pankera is in a different category, or at least is presented as such.

Anyhoo, my summary thoughts, opinions and advice:

- I found (particularly in rereading) many parts of Number annoying enough to skim/skip, particularly where our four protagonists take turns mindgaming the others, also where a few characters spend way too much time doing what Nero Wolfe (who does not appear in either Number or Pankera) might generously characterize as a stunt. By comparison, in Pankera, nobody got quite on my nerves as much, nor did any of the plot bits.

- OTOH, Pankera often has more characters deciding and explaining housekeeping/packing type details, beyond what I felt we needed. But easy to skim past.

- Number does more with the dingus in terms of Gay Deceiver (which I liked) than Pankera.

Beyond that, Sourdough Jackson’s review pretty much hits the mixed bag of goods and bads better than I can. I do agree with their analysis and opinions of the ending, and the overall plot driver.

One nitpick: While I’m not going to go back and re-skim to confirm, it feels like “Pankera” is used primarily as a singular, with “Panki” being the plural, which makes the book title misleading. (Also, it feels like the terms doesn’t occur in the text until about 40-50 pages after what they refer is introduced. If I had an e-version, I’ll text-search to verify. Meanwhile: Tsk.)

Assuming you’re enough of a Heinlein fan to be potentially interested — and have read enough later-Heinlein to know what you may be in for — I neither recommend you read Pankera nor avoid it. I don’t feel it’s annoying enough to warn you away — nor compelling enough to urge you to read it.

I don’t regret having read it; I’m not looking to get my time back. But I’m glad I did it as a library borrow. Back it goes! You’ve been advised!

Like I said, I don’t think this is a review so much as a verbose ACHTUNG! DER LOOKENSPEEPERS sign.