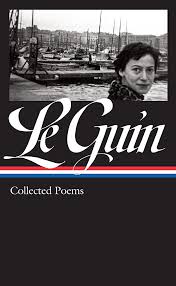

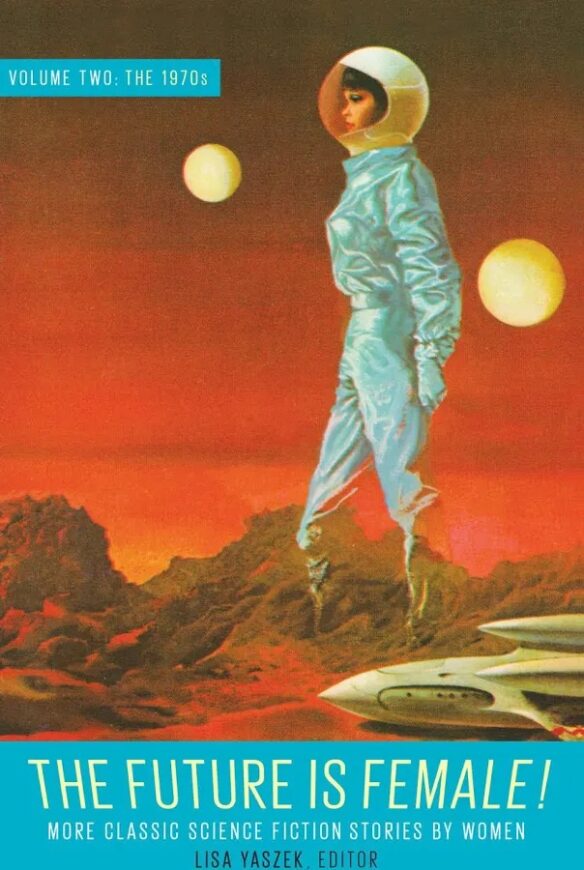

The Future Is Female! More Classic Science Fiction Stories By Women Volume Two: The 1970s. Edited by Lisa Yaszek (Library of America, 2023)

Review by Warner Holme: Lisa Yaszek’s The Future Is Female! More Classic Science Fiction Stories By Women Volume Two: The 1970s is a continuation of the previous volume from the same editor. Putting together a selection of stories from a more condensed period of time, this volume focused on a single decade nonetheless includes a fascinating assortment of material.

A very nice introduction by the editor provides context for the pieces in the collection as well as thoughts from individuals for working at the time. In addition there are a number of unadvertised pieces by women involved. Specifically, as early as page xiv there are illustrations from various SF publications which were created by women of the time. The first of these is a very nice figure originally in Galaxy magazine circa June 1975 which is by the well-known artist Wendy Pini. While these are a major surprise, they are all carefully credited and appreciated, although a few that definitely appeared in color are rendered in black and white.

“Bitching It” by Sonya Dorman Hess opens the volume with real action. While many think of the early 1970s as still a time when science fiction was clean and aspirational about the future, this piece is dark and twisted and grotesque in a way that seems well matching horror or dystopia of the time. Featuring everything from spousal abuse to dog attacks, it’s a strangely disturbing story that actually has a lot to say.

Another interesting piece is Elinor Busby’s “Time to Kill.” Featuring a mixture of disturbing thematic ideas for time travel and a strange look at the idea of time evening itself out, it begins with a woman running back to her time machine before flashing back to her decision to commit a very specific murder. Really it is extremely short and doesn’t do much that hadn’t been done before with the concept of time travel, however it does so in a very in your face way that addresses a problem of both rejecting the past and taking drastic action to make matters worse. On the other hand the fact a number of less severe solutions are offered and rejected in favor of a religious version of child murder could be seen as making the entire story at metaphor for avoiding extremism.

Wrapping up the book are a variety of nice biographical pieces on the offers as well as a very detailed selection of notes which occasionally include single commentaries lasting for multiple pages.

The biographies leave the reader in a strange position of remembering that this is one of the rare collections by Library of America in which a large percentage of the authors have passed on. This doesn’t so much affect the quality of the book as make it a very different read than one might have expected, at least with that little detail in the back of a reader’s mind.

The Future is Female! Volume Two represents a very nice companion.to the first book. While we mentioned stories each represent fascinating moments in the history of the genre, other included pieces are often brilliant and well-known, including the science fiction horror piece “The Screwfly Solution” by Raccoona Sheldon and Kate Wilhelm’s “The Funeral.” While not every story appeals to every taste, it does represent a fascinating book at that decade for women working in the field.