A regular exploration of public domain genre works available through Project Gutenberg, Internet Archive, and Librivox.

By Colleen McMahon: In the previous installment of this column, I began looking at early time travel stories, mostly involving some sort of magical or fantasy time travel. “Time slip” stories don’t explain much about the time travel mechanism. The character falls asleep and wakes up in a different time, or experiences the time travel as a dream or vision.

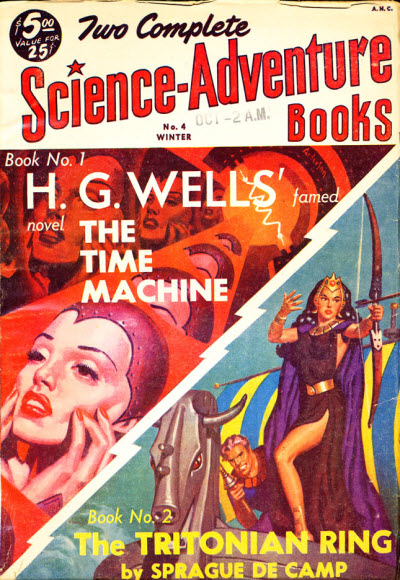

The rapid growth of scientific understanding coupled with the spread of industrialization laid the groundwork for more mechanized imaginings of time travel. The seminal work is, of course, H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine (4 Librivox versions available here). The idea of a machine that could carry passengers to a targeted point in time became one of the key tropes of science fiction. The Doctor’s TARDIS and other modern time machines are direct descendents of Wells’ machine.

Last time, I promised that this column would look at The Time Machine and the stories that followed it. However, most of the tales directly inspired by Wells are, unfortunately for my purposes here, still under copyright so I couldn’t go very far in that direction.

However, there are several intriguing stories that laid the groundwork for The Time Machine, including a mostly-forgotten tale by Wells himself. So I thought I’d dig into the forerunners of mechanical time travel instead.

1881 saw the publication of two stories that illustrate the emergence of “scientific” time travel.

The first, by Grant Allen, is “Pausodyne”. It appeared in Belgravia magazine’s Christmas Annual in 1881, and was collected in Allen’s Strange Stories in 1884.

“Pausodyne” combines a time slip — falling asleep and waking up in the future — with a science-based explanation. The narrator meets a man on the streets of London who is asking strange questions about coaches to Yorkshire and seems to be unfamiliar with the concept of rail travel. As they talk, the strange man reveals himself to be Jonathan Spottiswood, great uncle of the narrator, who had disappeared years before.

It turns out that Jonathan had been a “philosophical chemist” and had experimented in a hidden lab with a chemical concoction he called “pausodyne”, which produced a state of suspended animation. As he experimented with animals, one night he was overcome by the pausodyne fumes and fell asleep in his laboratory. When he woke and went outdoors, he discovered a completely changed world, and gradually realized that he had been in suspended animation for century.

It’s basically Rip Van Winkle with some chemical trappings, but it feels like a much more modern time travel story because much of it focuses on how confused Spottiswood is by the vast changes that have taken place in a hundred years. Time travel has become more interesting as a theme because there is now a real sense of transformation over relatively short time spans.

“The Clock That Went Backward” by Edward Page Mitchell appeared in the New York Sun in 1881. The time travel device is the titular clock, of course, which takes the narrator and his cousin 300 years backward to the siege of the Dutch city of Leyden. It’s one of the first stories that I know of with the trope of the time travelers themselves being the cause of well-known historical events, as well as one of the pair apparently becoming his own ancestor! (Audio version is included in Short Science Fiction Collection 50).

A timepiece, in this case a watch, is also the time traveling mechanism in Lewis Carroll’s last completed novel. Sylvie and Bruno is a 2-volume series of tales taking place in both Fairyland and our world, published in 1889 and 1893. Several of the stories revolve around a special watch, the “Outlandish” watch. This appears to be an early instance of an author working out “rules” for time travel, as in one case a character tries unsuccessfully to use the watch to prevent an accident from taking place in the past. They find that they can only witness events, not change them. (Librivox has both volumes, plus a dramatic reading version).

H.G. Wells published “The Chronic Argonauts” in his college newspaper in 1888, and it is a bit of a mess. Much of it is given over to describing the weird things that the inhabitants of a small village in Wales witness after a mysterious Dr. Nebogipfel takes up residence and begins doing strange experiments. Eventually the townspeople opt for the time-honored tradition of torches and pitchforks, only to find that the Doctor has vanished!

Several weeks later, the local minister who had disappeared at the same time turns up alone. He proceeds to give a deposition of “the murder of an old man named Williams, which occurred in 1862, this disappearance of Dr. Moses Nebogipfel, the abduction of a ward in the year 4003 —-…Also several assaults on public officials in the years 17,901 and 2.”

Unfortunately, we only get a portion of that before the minister expires. He does explain how he came to be traveling with Dr. Nebogipfel — he was visiting and talking with him on the evening the mob came, and is forced to depart with Nebogipfel out of fear that the villagers would kill him otherwise. The story ends frustratingly with the promising sentence, “The voyage of the Chronic Argonauts had begun.”

My biggest takeaway from reading “The Chronic Argonauts” is how much Dr. Nebogipfel sounds like the inhabitant of a certain blue police box. He is even repeatedly referred to as “The Doctor”!

One of the things that disquiets the villagers is the late night noises emanating from his house, thus described: “at first a complaining murmur, like the groaning of a wounded man, “gurr-urrurr-URR”, rising by slow gradations in pitch and intensity to the likeness of a voice in despairing passionate protest.”

When he suggests that the minister accompany him, the Doctor proposes, “I was thinking while I was . . . away . . . Would you like to come? I should greatly value a companion.” In the end, however, the arrival of the mob leaves him no choice. When the villagers break in, they are stunned — “For the calm, smiling doctor, and his quiet, black-clad companion, and the polished platform which upbore them, had vanished before their eyes!”

All of this sounds awfully familiar, no? I’m amazed that this hasn’t turned up as an episode of Doctor Who already, with the actual Doctor bringing about the events that led to Wells’ story. (Maybe the part of the story where Wells’ Doctor actually MURDERS the previous inhabitants of his mansion is too big an obstacle?)

On the whole, Wells’ The Time Machine is a much better piece of work, but you can see the seeds sprouting in “The Chronic Argonauts”. Sadly, there is no Librivox recording of the piece yet.

I hope you have enjoyed this side trip into time travel tales; I’ll be back to more random ramblings next time!

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Something like that does occur in a Sixth Doctor story “Timelash” – which has a character named Vena, creatures called Morlox and an 19th century fellow named Herbert.