By Rich Lynch: It was 80 years ago that an extraordinary event took place.

It happened on January 3, 1937, in the English city of Leeds. It was there that a group of science fiction fans gathered for what has been described as the first-ever science fiction convention.

What records remain of the event indicate there were fourteen people in attendance, several of whom would go on to become luminaries of the science fiction literary genre: Ted Carnell, Walter Gillings, Eric Frank Russell, and Arthur C. Clarke. It was a single-day conference, hosted by the Leeds branch of the newly-formed world-wide Science Fiction League of fan organizations. The day featured speeches and testimonials on various topics related to science fiction and after that, group discussions on “ways and means of improving British science fiction” according to a one-off fanzine published soon afterwards which reported on the proceedings. What resulted was the formation of the Science Fiction Association, a proto-British fan organization centered around the “four Hells” fan clubs in Leeds, Liverpool, London, and Leicester. It only lasted about two years, due to the onset of the Second World War, but it did set the stage for a permanent organization, the British Science Fiction Association, which eventually came into existence in the 1950s.

That 1937 convention was truly a seminal event, and it helped pave the way toward the promulgation of science fiction fandom throughout the United Kingdom. But was it really the first science fiction convention?

Maybe not.

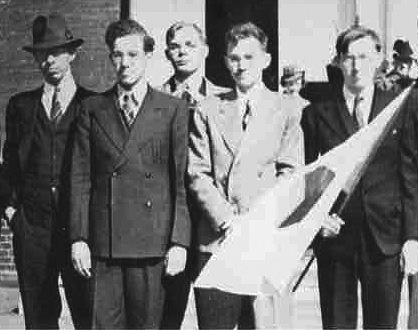

Donald Wollheim, Milton Rothman, Fred Pohl, John Michel, and Will Sykora at the

1936 Philadelphia convention.

On October, 22, 1936, about half a dozen fans from New York City traveled by train to Philadelphia, where they convened for several hours at the home of one of the fans there. In all, there were a similar number of fans brought together as for the Leeds convention. What made it a convention, in the minds of its attendees, was that a business meeting was held with the host, Milton Rothman, being elected Chairman. Fred Pohl, who had been designated the Secretary, took the minutes and then subsequently lost them. But Pohl later stated that no recordable business had been brought up because the event had only been informal in nature, with fans talking to fans about things like which books they had recently read, which authors they liked, and what they hoped these authors would write next. The most significant outcome was that everyone had such a good time that a follow-up event was held in New York in February 1937 with about 40 fans attending. This created the momentum for an even bigger event, a bit more than two years later which was held in New York on July 4, 1939 – the first World Science Fiction Convention.

Those first two fan gatherings have been a source of continuing controversy ever since then. Which one was really #1? The Leeds convention was the better planned of the two, with groundwork laid for the event several months earlier – the Philadelphia convention was, according to accounts from several fans attended it, mostly spur-of-the-moment with little advance preparation. There has been speculation that the only reason that the Philadelphia event occurred at all was because of one-upsmanship. The idea for that gathering was originally put forth by New York fan Don Wollheim, who back then had gained the reputation for being quarrelsome, antagonistic, and more than a bit provocative. It’s very possible, even likely, that he knew of the upcoming Leeds event, which had been talked up not only throughout Britain but also in some U.S. prozines. So, supposing the underlying reason for the Philadelphia meet-up was really only to sabotage any Leeds stake to being the first science fiction convention, should that disqualify Philadelphia’s claim for that distinction?

No, that’s insufficient. There have been other conventions that have been organized on little more than a moment’s notice and in any event, overall intent is irrelevant – you can hold a convention for any purpose you want. A much better reason for possibly honoring Leeds as #1 is that the Philadelphia event was an invitational gathering not open to the general public, with only the New York and Philadelphia fan clubs involved. But this, too, does not hold very much water as there have subsequently been other, in effect, invitation-only conventions, including the very first DeepSouthCon. And one other criticism of the Philadelphia event’s claim for being #1 is that there was “no recordable business”, very little reportage after the fact, and indeed, not even a program. But this is the weakest argument of all, and one only has to point toward the annual Midwestcon conventions, which also have none of these, as a refutation.

And so the controversy has lingered for all this time. The 1936 Philadelphia event was first chronologically, but was it a convention or just a meeting? In the end there probably will never be a consensus – after eight decades this is still perhaps the most polarizing topic in all of science fiction fandom, at least from a historical perspective, and people will believe what they want to believe. But there have at least been attempts at finding some middle ground. Noted fan historian Mark Olson, in Fancyclopedia 3, has suggested that: “Perhaps it would be fairest to say that the first thing that could be called a convention was held in Philadelphia in 1936, while the first thing that must be called a convention was held in Leeds in 1937.” And he’s right.

But as for me, I think we are asking the wrong question. What we instead should be inquiring is: “Who first came up with the idea for staging a science fiction convention?” That’s really the more important aspect, and the Leeds group was first. There’s serendipity that they held their event at the Leeds Theosophical Society – the word ‘theosophy’ parses to ‘divine wisdom’, which is an apt description of the concept for the science fiction convention. And of that, at least, we can be absolutely certain!

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

I grew up in Philadelphia, and was a member of the Philadelphia Science Fiction Society. Local lore had it that a group of NYC fans led by Sam Moskowitz (who I knew back when) took the train down to Philly to meet with Philadelphia fans led by Ozzie Train (who I knew back when), whom they knew by correspondence through letters to the prozines and fan publications.

What was significant to us was that it was the first time groups fans from different US *cities* had met in person, and as such was the progenitor in the US of later actual SF cons. We considered the 2011 Philcon to be the 75th anniversary of that event.

Do records exist that specify where the folks attending the Leeds event came from?

______

Dennis

Rob Hansen’s “Then” has the details – 6 were from other parts of the country, specifically Carnell, GIllings and Clarke travelling from London, Hanson from Leicester, and Russell/Johnson from Liverpool.

Okay, thank you. (Then is available at http://fanac.org/Fan_Histories/Then/)

That’s a decent distribution, and takes it out the the “Leeds local event” category.

If folks in the UK want to consider the Leeds event to be the first one specifically *planned* to be an SF con, I won’t quibble.

______

Dennis

In these days of ultra-nationalism, its probably best not to discuss this too much, but I think that this issue is settled, although unsatisfactorily:

Philadelphia was the first, if only because Wollheim planned it to upstage Leeds.

If you are planning on upstaging an actor in a a play, you don’t do it by opening a hotdog stand on a corner in a different city, you do it on the same stage with acting.

Regardless of motivation, Philadelphia was the first convention. It deliberately met with the requirements of the day – fans traveling for a meeting. The Philly group went the extra mile by appointing officers, taking minutes (now lost) and conducting themselves in a manner that would be replicated at later conventions; they could have gotten together to play softball or to launch mail rockets or to pay a committee visit on one of the magazine offices or to chart out the tenets of MIchelism.

They did not. They had been planning a convention so they could claim the first con, and they accelerated their plans when they learned of the Leeds meeting. Leeds could have accelerated their plans if they had learned of Wollheim’s gambit.

I think it pretty clear that we have to give “the first” to the Philly crowd, while Leeds can certainly still claim that it was the first convention not held to upstage the first convention.

@steve davidson: I am unimpressed with your reasoning; IMO the Philly gathering was, among other things, short on heterogeneity. (“Invitational” is not narrow enough in describing this event, contra Rick’s summary; they could perfectly well have invited like-]minded[ people from other cities, as there was considerable correspondence going on by then.) It’s not quite as artificial as the UK “premiere” of The Pirates of Penzance (by a touring company in the sticks, purely to lock down copyright while the real premiere happened in NYC for the same reason), but it smells — even worse with the suggestion that it was set up specifically to upstage a properly public event.

@Chip: A thought experiment. Let’s suppose that Wollheim did let one other person he was friends with, from some other city, know about the Philadelphia event and further suppose that one person had attended. How would this affect your conclusion?

@steve davidson: Philadelphia was the first, if only because Wollheim planned it to upstage Leeds.

Got a cite for that? It’s entirely possible, but I don’t recall hearing of it as a motivation for the NYC-Philly fan meetup.

Wollheim was certainly competitive. I recall a review of Sam Moskowitz’s The Immortal Storm” about the early days of fandom where the comment was that it all sounded properly cosmic and earthshaking, till you stepped back and recognized that he was talking about a bunch of teenage boys arguing in a basement. The whole tempest in a teapot over Michelism was a prime example, and the underlying motives were about perceived status in the community. (“I’m more important than you!” An awful lot of what goes on in fan circles is still that sort of thing.)

A lot of this revolves around definitions. The first con I attended was Philcon in 1968. A co-worker saw me reading a copy of Analog and said “You read SF?” “Yes.” “Are you going to the con?” “What’s a con?” He told me about Philcon, I attended, joined the sponsoring organization, and found myself running it in the mid-70’s before moving to NYC. I’ve stayed involved in con running off and on ever since.

But the answer to “What’s a con?” has likely changed a bit over the decades. I wonder what some of the old timers no longer with us would think if you could go back in time and tell them about how what they were involved in would grow and develop.

______

Dennis

@Rich: consider this thought experiment: what if Wollheim had actually invited any fraction of the correspondents he was on good terms with at that time? I am not going to argue the one-drop theory.