[It’s hard to believe King Kong could sneak up on anyone. But in a way that happened to Steve Vertlieb.]

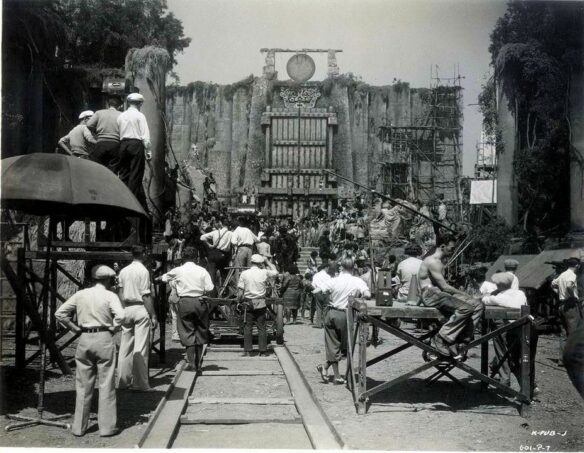

By Steve Vertlieb: Merian C. Cooper’s celebrated gorilla was born in the mind of his creator, perhaps, as early as 1927 when his friend W. Douglas Burden, a Director of The Museum of Natural History in New York City, published his book “The Dragon Lizards of Komodo.” Burden’s historical volume on the nine foot, carnivorous lizards occupying Komodo Island in the East Indies set the film director’s fertile imagination ablaze with thoughts of giant, prehistoric creatures marauding through a lost island, set apart from the rest of the world, unchanged since the beginning of time. Cooper and his partners, Ernest B. Schoedsack and Marguerite Harrison, had been filming acclaimed documentary features concerning primitive cultures and civilizations for “silent” cinema. Grass, released in 1925 and Chang, released two years later in 1927 recounted their encounters with prehistoric tribal customs passed from generation to generation, untouched by societal evolution. Purchasing two cameras and fifty thousand feet of film, the adventurous trio ventured courageously to the Persian Gulf where they filmed the annual migration of the Bakhtiari people. Upon completion of the “shoot,” Cooper, Schoedsack, and Harrison returned to Paris where they processed the footage by themselves. Jesse L. Lasky purchased the finished print for his Paramount Studios, and the film, now titled Grass, enjoyed a successful run both in The United States and abroad. Excited by their success, Lasky dispatched the team to Siam to film a scripted action/adventure yarn in the deep jungles of the region. Released in 1927 by Paramount, Chang again drew huge audiences and probably inspired later features and serials featuring the jungle exploits of both Frank Buck and Clyde Beatty, as well as MGM’s decision to green light Trader Horn, and its enduring series of “Tarzan” films.

Not content to rest on their collective laurels, Cooper and Schoedsack once again journeyed to the “dark continent” in order to film “location” footage for their big budget film version of Four Feathers. Billed by Paramount as “The last of the big silent films,” the adventure classic tale of cowardice under fire, released in 1929, featured Richard Arlen and Fay Wray as war time lovers torn apart by false accusation and bravado. Cooper’s growing experience as a film producer would inevitably lead him to more fertile fields of live action production and storytelling, and so he embarked upon a most dangerous game of chance. Working from a premise involving the turning of tables in which the hunter might now become the hunted, the cinematic adventurers decided to produce a film based upon Richard Connell’s classic tale of role reversal. Published as a short story in 1924 as “The Hounds of Zaroff, The Most Dangerous Game was a natural progression for the maturing wildlife film makers. Man would become the prey, while a crazed big game hunter, bored by matching wits with four-legged predators, might now trap and destroy “the most dangerous game of all,” his own species. Directed by Irving Pichel along with Ernest B. Schoedsack, and released by Radio Pictures in 1932, The Most Dangerous Game Starred Joel McCrea as a celebrated big game hunter deliberately shipwrecked at sea in order to lure him to a private island owned by the mad Count Zaroff. Leslie Banks as the demented recluse welcomes “guests” to his deserted island in order to hunt them down by dawn, and add their heads to the walls of his hidden trophy room. Fay Wray once again was the object of mutual desire, while Robert Armstrong as her often inebriated brother, provided Banks with his less than satisfactory prey. With a thrilling score by Max Steiner, as well as a cast and crew that would soon become family, The Most Dangerous Game was setting the sound stage for its sister production, being filmed simultaneously on those most dangerous sets.

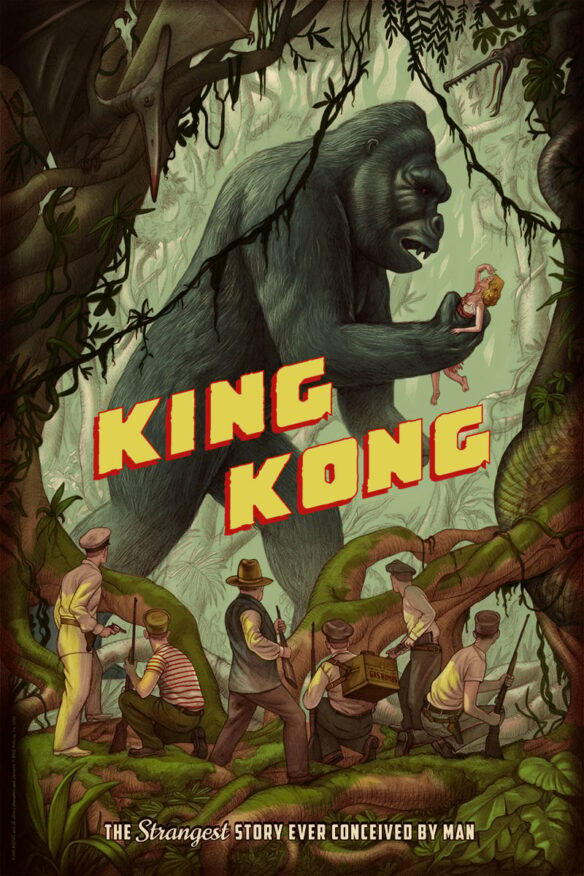

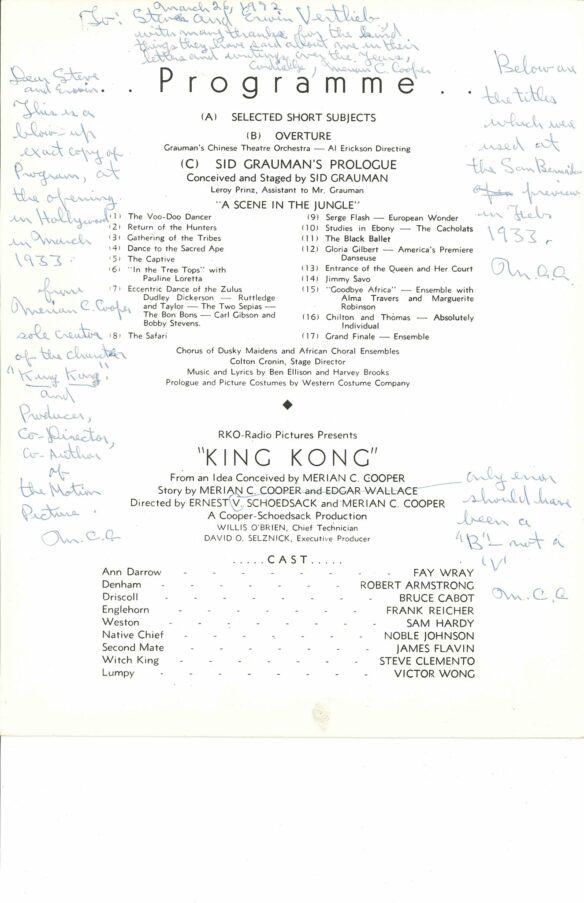

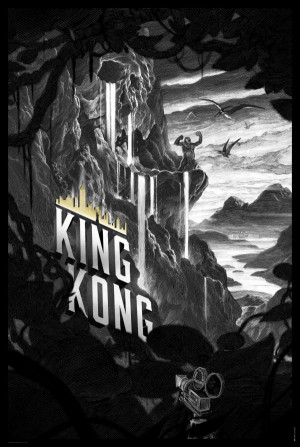

King Kong related the remarkable tale of a giant beast, an impossible ape-like creature whose imposing, horrifying shadow would follow the intrepid explorers whose heroic exploits had led them to its discovery. Released by RKO Studios during the winter of 1933, the picture reunited Fay Wray and Robert Armstrong with Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack for yet another thrilling adventure in the lurid jungles of a primordial world. They were joined by Bruce Cabot in, perhaps, the pivotal performance of his career. Filmed and released during the height of America’s great depression, the film followed a crew of shipwrecked survivors as they valiantly struggle to escape overpowering odds, caught in the crosshairs of economic upheaval. Adrift at sea amidst the mocking skyscrapers of a bankrupt metropolis, a documentary film producer (patterned after Cooper himself) flees the merciless boredom of repetition in search of new worlds. A conqueror at heart, Carl Denham yearns for new challenges, new discovery, and new opportunities to break through the molding memories of his own worn career. He is given a map of a strange, prehistoric island in which creatures from the dawn of time still exist, exalting a towering monstrosity who reigns supremely in a lost corner of a shrinking planet. Their aged freighter, crashed cruelly against marauding waves, sends a cautious expedition to the uncharted island, barely escaping the wrath of the native inhabitants of Skull Island, a terrifying precipice on the wretched edge of treacherous seas.

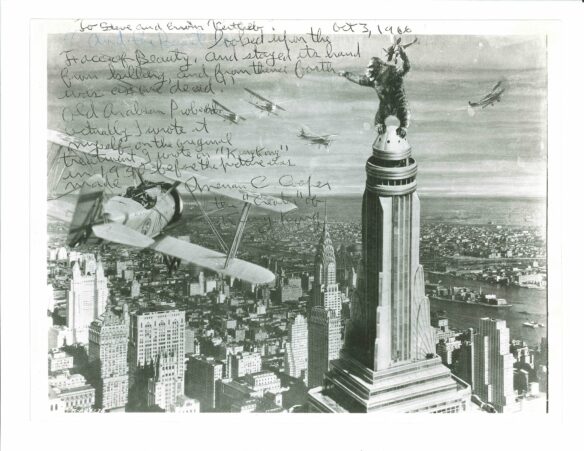

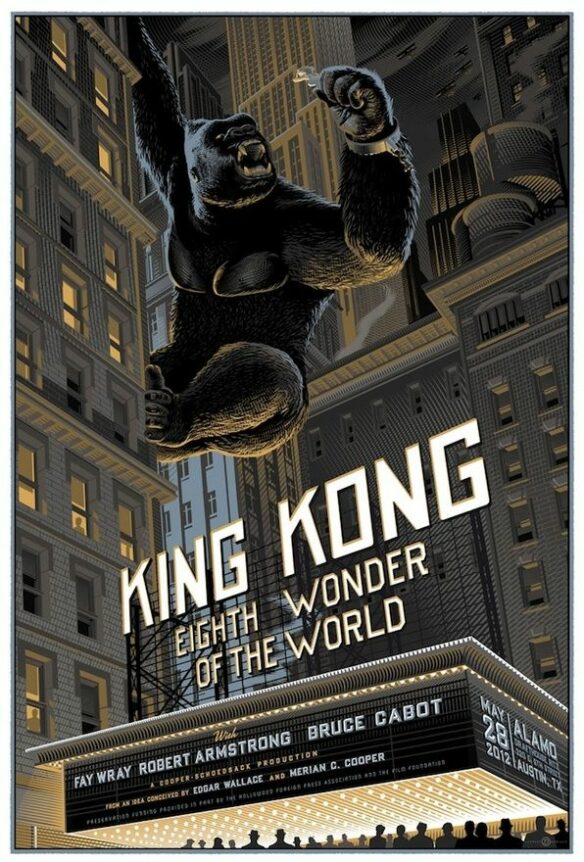

There, amidst ravenous swamps and savage tribes, live the remnants of man devouring dinosaurs and a fierce monolithic gorilla whom the natives call…”Kong.” He was a king and a god in the world he knew, a triumphant titan rampaging majestically through savage jungles, a towering prince among lost horizons. Fearless and unchallenged, either by gods or by men, Kong is ultimately defeated by the technological slings and arrows of outrageous fortune. Wielded by Lilliputian invaders, gas bombs transposed from another reality ultimately devour this courageous denizen from the beginning of time, bringing him to his knees in choking slumber. Mighty Kong is transported by tramp steamer to the unforgiving jungles of New York where he is displayed, a fallen angel cursed by the stars, exhibited in chains against a burning cross. He is a noble figure, a Christ-like martyr suffering for the sins of humanity. The purity of his primordial existence has been betrayed. He is a tortured innocent, imprisoned in a world beyond his conception or forgiveness. His final redemption, breaking free from the shallow bonds of captivity, leads him irretrievably to his fate amongst the stars from which he came. In raging fury, Kong lords over the steel canyons of “civilization,” perched valiantly atop the highest mountainous peak in the city. The tower of the Empire State Building, its cratered caverns shuddering beneath the roars of her unwelcome captor, becomes the last tragic refuge of this embattled slave. Slaughtered by unforgiving machine gun bullets, Kong topples to his death miles below upon the ferociously mean streets of the cruel, naked city.

Merian C. Cooper’s classic fantasy adventure remains, perhaps, the most celebrated retelling of “Beauty and the Beast.” Its martyred protagonist, an antihero for the ages, profoundly influenced generations of film makers and fans, charting the career choices of Ray Harryhausen, Ray Bradbury, Peter Jackson, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg among so many others. Kong’s strangely passionate love for Ann Darrow, the symbolically virginal heroine played by Fay Wray, creates an open wound of masculine loneliness that leads unrelentingly to his slavery and demise. Its rich violent symphonic themes, created by Max Steiner, contributed to one of the first important film scores of the sound era, a landmark musical achievement that would set the standard for all subsequent Hollywood soundtracks. King Kong was, in its time, a marvel of visual, special effects technology. Willis H O’Brien, who created the stop-motion effects that so effectively brought Kong to life, virtually invented the craft, illustrating the original silent version of Arthur Conan’s Doyle’s The Lost World (1925). He would pass the torch to Ray Harryhausen during the filming of Merian C. Cooper’s Mighty Joe Young some sixteen years later. The story of King Kong has endured a lasting cultural significance in the years since its original release, and has found a home in the deepest recesses of our collective culture, dreams and nightmares.

Perhaps, it should have come then as no surprise when in 1976 not one, but two motion picture studios were competing for the chance to bring Kong back to the big screen. Universal was planning a large-scale remake of the venerable tale with stop motion cinematography by animator Jim Danforth who had worked with George Pal on The Seven Faces of Dr. Lao, as well as creating many of the effects for ABC Television’s The Outer Limits series. Meanwhile, Paramount Pictures was plodding ahead with their own big screen remake of the cherished screen fable, under the auspices of producer Dino De Laurentiis. De Laurentiis mounted an enormous publicity campaign which, sadly, ruled the day. Universal backed off of their more ambitious filming, and Paramount found itself the only player on a creatively diminished field.

Unlike Universal, whose own scenario might have been truer to the integrity of the original production, Paramount decided upon a less costly proposal. Whereas Universal, along with animator Jim Danforth, would have utilized Willis O’Brien’s cherished, though laborious, methodology of stop motion animation, Paramount’s production team decided to populate Skull Island with elaborate puppets and men in rubber suits. De Laurentiis both angered and alienated the fan community by belittling the achievements of Willis O’Brien, proclaiming sanctimoniously that the visual effects in the original picture might have been adequate for their time, but that technological advancements by 1976 had far surpassed the primitive stop motion effects of 1933. When Paramount’s version of King Kong was finally released in 1976, both the picture and its highly touted visual technology became the laughingstock of the industry, and an embarrassment to the studio. De Laurentiis had constructed an enormous mechanical gorilla that barely moved or functioned. It was used, ultimately, only for longshots in the completed film and, during its well publicized unveiling for the press, leaked motor oil all over itself. A primordial diaper might have saved the day.

Directed by John Guillerman, and written by Lorenzo Semple, Jr., who rose to prominence writing ABC Television’s campy Batman series, the film featured a cast that included Jeff Bridges, Charles Grodin and, in her very first screen appearance, Jessica Lange. Lange would, of course, overcome this inadequate debut with numerous brilliant performances in the years that followed…but everyone has to start somewhere. The script for the film was decidedly “Semple” minded. Jack Kroll in his review for Newsweek noted the Kong’s roar sounded like “the flushing of a thousand industrial toilets. The sole creature besides Kong residing on the once lushly inhabited island was a laughably inadequate “serpent” whose guarded movements were pulled by marionette strings worthy of Howdy Doody. Rick Baker performed valiantly inside the human-scaled King Kong suit, but his performance was ultimately marred by the mediocrity of the production’s budget and script. The one memorable aspect of an otherwise ludicrous attempt to surpass a fantasy masterpiece was John Barry’s eloquent, if somber, musical score which seemed written for something other than the ill-fated atrocity in which it appeared. In the end, to paraphrase Merian Cooper’s poetic finality, “Twas Was Dino Killed The Beast.”

THE ONCE AND FUTURE KONG

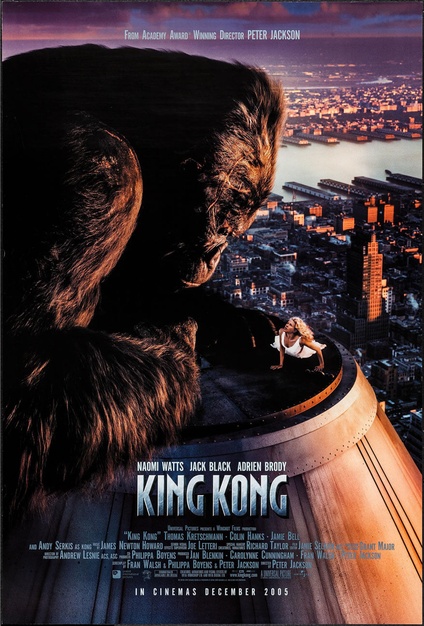

Despite well-intentioned proclamations by the New Zealand monarchy, a carefully positioned ascension to the throne has come unraveled by a tainted blood line. The ape who would be king, however noble, remains relegated to a lesser chamber in which countless pretenders share unfulfilled delusions and dreams of grandeur. After years of plotting and grand design, Peter Jackson’s Richelieu has failed his King. The years of promise have ultimately worn thin with expectation, and the director’s creative pregnancy has yielded a stillborn creation. King Kong is classic in its betrayal of the seed that inspired its birth. Upon completion of the greatest fantasy film trilogy ever made, The Lord of the Rings, it appeared that Peter Jackson was the perfect candidate to direct a modern re-telling of Merian C. Cooper’s exquisite fable of beauty and her beast. After all, he was a consummate, passionate filmmaker whose creative inspiration matured in the profound shadow of a masterwork. Who better than Jackson, then, to return the legendary gorilla full circle to his rightful place among the technological marvels of digital supremacy? And yet something went horribly wrong. Somewhere along the yellow brick road, purity of purpose surrendered to commercial sensibility, while humility and childhood wonder expired cruelly within the depths of an artificially conceived Depression. Expressing a life-long desire to re-imagine and recreate the masterpiece that gave birth to his own artistic dreams, Jackson at last had the economic clout to bring his boyhood vision to the screen…a limitless expansion of prehistoric wonder. That he failed is a tragedy, both for the millions of fans who placed their hopes so earnestly in his care, and for the beleaguered film industry whose faith and economic carte blanche lay ravished and torn in the spider pit of arrogance and deception.

Signs of trouble loomed late in production when, defiantly defending his significant alteration of the story, Jackson proclaimed that the original screenplay wasn’t so great to begin with. Now the director, like Dino De Laurentiis before him, was going to improve upon a masterpiece with another Semple-minded revision of the text. Nagging questions remained, however. If the original film inspired and ultimately sired Peter Jackson’s love of movies, leading to his burning ambition to bring his favorite motion picture back to its original glory with a new and reverent visualization, when did his respect for its sublime simplicity fall so callously from the cliffs? When De Laurentiis assumed godlike pretensions, asserting that a simple man in a gorilla suit would surpass the technological innovations of Willis O’Brien’s Stop Motion creations, Twas Dino Killed The Beast. When Jackson decided that the magic which so pervasively enchanted his childhood dreams was corny and imperfect, he burned the very structure he would build upon…leaving a flimsy fortress adrift in weightless clouds. That these revisions and supposed improvements would ultimately collapse beneath the weight of their own self importance was as certain as Kong’s fall from the silver dome of the Empire State Building. Only a blind man could miss the inevitable signs of danger…or a filmmaker blinded by righteous self deceit and stubbornness of heart.

Peter Jackson’s King Kong opened on December 14, 2005 to thunderous critical response and disappointing audience participation. Perhaps the critics who so slavishly praised the spectacle of the Universal release were so intimidated by the grim reality of diminished box office returns and attendance that they feared for their pensions and job security. Blinded by studio subsidies and their own imagined importance to the struggling film industry, perhaps they truly never entertained the terrifying notion that the King had no clothes…that the single motion picture upon which Hollywood had placed its dreams of economic recovery was left naked and prone upon the barren streets of 1930’s New York.

Divided into three separate sections, as was the original film, Jackson’s King Kong begins appropriately on the East Coast where a carnivorous film director is fighting for his future with his usual assortment of lies, half truths and infectious bravado. Better than expected, yet still woefully miscast as Carl Denham, Jack Black is an unscrupulous and nefarious incarnation of the vibrant, exciting and joyous persona enacted by Robert Armstrong in the original. His Denham is neither passionate, nor attractive. Armstrong’s Denham was proud and profane, enthusiastic and exuberant, a leader one might follow into the gaping jaw of a hungry lion. His Denham inspired loyalty and courage in the blood of his crew. The new and improved Denham is more ruthless, a single dimensioned stereotype more likely to attract attorneys and bill collectors than respect and obedience. He is a thoroughly despicable character, lacking charm or magnetism. He is, however, a charming persona compared to the unfortunate casting of Kyle Chandler as leading man Bruce Baxter in what must surely be the most significant miscalculation since George Lucas invented Jar Jar Binks for Star Wars: The Phantom Menace. The decision to write in so buffoonish a comic stereotype in the midst of a classic romantic tragedy is beyond comprehension, forcing one to wonder seriously what devilish impulse possessed Jackson to so consciously sabotage this supposed homage to his favorite film. Imagine, if you will, Bruce Baxter’s namesake, Ted, emerging from the newsroom of the Mary Tyler Moore program to join the intrepid adventurers of Skull Island. Consequently, much of the film’s first hour is virtually intolerable, creating a burlesque atmosphere that severely cripples a third of the film.

Astonishingly, the picture takes a dramatic turn for the better when the Venture and her crew reach the island shaped liked a skull. Striking camera work and artistic design illuminate a strange, brooding terrain seemingly lost in time. There is much to admire in the center sequence occupying the next hour of Jackson’s vision, although the great wall separating the frightened natives from their prehistoric neighbors is disturbingly reminiscent of a similarly funky structure in the Dino De Laurentiis atrocity of 1976. Additionally, the perfectly-synchronized apparatus delivering the sacrificial maiden to her captor seems well beyond the conceptual imagination of the inhabitants of the massive island. Jackson’s reasoning in transforming his protagonist from a frightening, mythological creature to a more accessible silver back gorilla is similarly confusing, as Kong was described in the original screenplay he so admired as “neither beast, nor man.” Still, the primordial occupants of this Jurassic Park remain fearsome reminders of the vanishing separation between savagery and the mannered pretense of civilized society. Kong’s battle with a ferocious Tyrannosaurus is an exhilarating showpiece, thrillingly restoring the original conception to a new, spectacular plateau. Re-conceptualizing the infamous, ultimately deleted Spider Crab sequence from the original picture presents a ghastly, blood chilling representation of what the stranded crew might have encountered after being hurled from the log into the ravine far below. It is a wonderfully realized sequence, not intended for squeamish theatre goers.

If Jack Black presents an unflattering portrait of the adventurer patterned in reality after Merian C. Cooper, then Oscar-winning actor Adrien Brody as a more sensitive Jack Driscoll literally flounders under the enormous weight of Jackson’s overbearing plot contrivances and special visual effects. His characterization and performance, though no fault of his own, are largely consumed by the more urgent demands of rampaging dinosaurs and throbbing primordial libidos. If there is an outstanding performance by a terrestrial performer, it is most certainly given by the lovely, gifted Naomi Watts as heroic Ann Darrow, the romantic illusion tempting the noble beast from his lonely lair. Their affection for one another is genuinely touching, although one wonders with fascination which is the canine and which is the master. They appear at times interchangeable in this ultimate pet movie. Watts is effervescent and delightful as the unemployed actress who finds love in all the wrong places. Jackson’s sense of humor seems ill at ease, however, amidst terrain in which he should have felt supremely confident. In a sequence ill advised and conceived, Ann recalls her background in burlesque, performing acrobatic somersaults and dance routines for Kong’s amusement. It is awkward at best…embarrassing at worst. Similarly confounding is Jackson’s decision to house Driscoll in a cage aboard ship as he types his dialogue for the picture within a picture… an unfortunate development intended, perhaps, as lowbrow humor.

Kong himself is a majestic conception, as performed and enacted by the gifted Andy Serkis who so wondrously brought Gollum to life in The Lord of the Rings trilogy. He is a great, lonely creature inhabiting a world devoid of his kind, a noble remnant of a time long forgotten…a King and a God pathetically adrift in the world he knew. Lured from comparative security by forbidden love, he is captured and imprisoned amidst a shining corridor of glass and steel to face a more sophisticated savagery than he encountered on the island. Returned to New York as a captive to gratify human curiosity, he becomes once more a Christ-like figure sacrificed upon the altar of mortal greed and jealousy. Yet again, however, Jackson chooses to bow to his inner demons, rather than retain the enormous integrity of an earlier vision. Whereas Kong found redemption and escape within the walls of the great Shrine Auditorium in the first film, his New York debut here is relegated to the stage of a minor music hall. In his own puzzling film debut, frequent Jackson musical collaborator Howard Shore portrays the conductor leading the tacky ensemble on stage in a bizarre performance echoing the staggering native dance and sacrifice on Skull Island from the original masterpiece. Jackson considered Shore’s score for the new film inadequate, firing him after the completion of his work. While James Newton Howard strove nobly to orchestrate a new symphonic accompaniment after the severing of Shore’s association with the director, there simply wasn’t enough time remaining to create a more significant work, leaving the final composition merely competent. The most memorable musical scoring in the picture is left to the remarkable ghost of Max Steiner whose impressive themes from the dawn of sound echo triumphantly in the final moments of this ponderous fantasy.

Among the more troubling omissions from Jackson’s homage is the legendary attack upon an elevated train, transporting exhausted commuters from their jobs to home and hearth they would never see again. Inexplicably, with the limitless financial resources available to his crew, the director chose instead to occupy the marauding ape with the paltry rewards of a careening bus on the streets of Times Square. Despite its provocative flaws, both King Kong and its controversial director have managed to elevate the final classic sequence to a moment of rare and exquisite beauty, magically transforming an adventure fantasy to glorious visions of incomparable nobility and tortured romanticism, reaching toward ethereal heights of the Empire State Tower, wondrously re-imagining one of the most glorious sequences in film history. In retaining sacred fidelity to the final tragic consequence of KONG and his ethereal quest for fruition of an impossible love, Jackson has recreated with consummate artistry the heartbreaking resolution of a timeless fable. Would that the rest of his journey had been as satisfying. As for The Once and Future Kong…the King is Dead…Long Live his immortal, poetic soul.

++ Steve Vertlieb — December, 2005

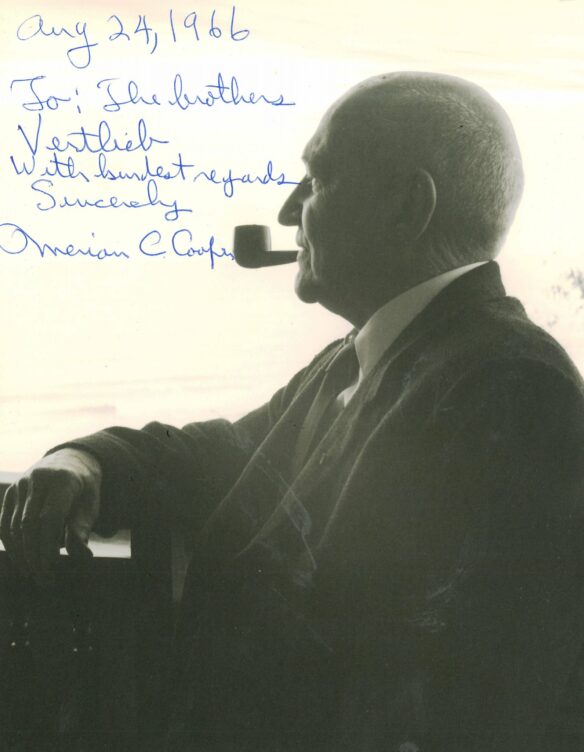

KING KONG TRIUMPHANT

Nearly twenty years have passed since Universal re-entered the simian playing field, releasing Peter Jackson’s much anticipated remake of King Kong in 2005. I was among those both excited and apprehensive about this second remake. Merian C. Cooper’s 1933 masterpiece remains my all time favorite film. I would guess that I’ve seen it over two hundred times over the past sixty odd years. I was fortunate to have known Merian C. Cooper through intensive correspondence for the last eight years of his life, and spent two wonderful afternoons with Fay Wray at her Century City apartment in Los Angeles after his passing. During the Summer of 1980, I was privileged to visit the home of this visionary filmmaker, enjoying several hours of conversation with his widow, actress Dorothy Jordan (who bore more than a passing resemblance to Fay Wray), and son, Richard Cooper who arrived to chaperone the meeting. I held Cooper’s original bound script for “Kong” (with his handwritten annotations delightfully populating its pages) in my hands, and stood excruciatingly near the infamous, framed portrait of Cooper drawn in caricature, yelling “Make It Bigger,” given the director during Christmas, 1932, by Kong’s cast and crew. No other motion picture has continued to mesmerize me the way that King Kong has, and I jealously guard its reverence in my life. When Dino De Laurentiis produced his 1976 atrocity, I was enraged. I managed to compose a sarcastic diatribe for George Stover’s Black Oracle Magazine which I laughingly labeled “Twas Dino Killed The Beast.” After that despicable debacle, I had little interest in seeing yet another remake of the fantasy classic…until, that is, it was announced that Peter Jackson would film his own loving tribute to Cooper’s masterwork.

Having seen all of the Lord of the Rings films, I became convinced that if anyone on the planet could bring Kong convincingly back to the screen, it would be Peter Jackson. His towering reign over modern fantasy films established his reputation as their preeminent interpreter. Add to that his stated reverence and respect for the original Kong, and the fact that it was the picture that inspired him to become a director in the first place. This was going to be a King Kong for the ages, I believed. The fact that the picture was scheduled to premiere the night before my sixtieth birthday added a mystic touch to an already exultant anticipation of the long-awaited unveiling.

I suppose that, in reality, not even Citizen Kane could have withstood the intensity of expectation surrounding the finality of completion of this deliriously anticipated remake. I walked into the theatre with stars in my eyes, only to exit three hours later deeply angered and insulted by what I regarded as an arrogant betrayal of the faith I had naively placed in Mr. Jackson’s integrity. I was actually quite horrified by the inanity of sequences flashing by me in numbing profusion. Jackson, I felt, had taken one of the screen’s most colorful, courageous characterizations, and turned it into buffoonish parody befitting the vaudeville theatrics so shabbily re-created in the film’s early scenes. No longer a fearless adventurer, director, and explorer, so enthusiastically patterned after Merian C. Cooper’s own heroic persona, Carl Denham (in the person of John Belushi wannabe Jack Black) had inexplicably been rendered impotent by the calculated degeneracy and burlesque simplicity of Black’s insultingly exaggerated comedic mediocrity. As if this wasn’t bad enough, Jack Driscoll…the hero of the original motion picture…had been reduced to a joke, a one-dimensional caricature reminiscent of newsman Ted Baxter on the Mary Tyler Moore television show. Jackson’s apparent dislike for actor Bruce Cabot, who portrayed Driscoll in the first film version of “Kong,” seemed exacerbated by his refusal to acknowledge Cabot in the final screen credit honoring everyone in the film other than the actor.

I wrote a scathing attack of Jackson’s production for a popular science fiction website during Christmas, 2005 promptly, if improperly, dismissing the entire film as an embarrassment to everyone concerned. After my review appeared, I began receiving a barrage of criticism from longtime friends around the country, roundly challenging my observations. The thrust of the observations concluded that I had been too hard on the film, unfair in my expectations, and blinded to its many charms. Even my own brother telephoned me upon leaving a Los Angeles theatre, raving about the spectacle and commending Jackson’s directorial brilliance. Most of the country’s major film critics, including Roger Ebert, praised its incomparable artistry and imagination. I thought, perhaps, I’d seen a different film than everyone else. Most of my friends urged me to wait a week or two, and go back to the theatre with a more open and, perhaps, generous mind. Maybe, now that I knew what was wrong with the film, I might be better prepared to sit back, relax, and enjoy what was right with the picture. About ten days later I did revisit the film and, in all candor, found that there were enough genuinely impressive set pieces to take the edge off of my initial resentment. Upon a second viewing, I composed a not entirely enthusiastic retraction of my earlier comments and, while unable to accept the new representations of Denham and Driscoll entirely, found that I had begun to like, if not love, the Jackson production.

When the film found its initial entry to the DVD market some years ago, I found myself watching it a third time. To my consternation, I discovered that I was really beginning to enjoy the movie. The Jack Black introduction, which had seemed interminably long upon its first viewing, had inexplicably grown less offensive and even shorter than I had remembered it. By time the Venture had run aground on Skull Island, the excitement and pacing of the film had increased dramatically and I found myself caught up in the breathtaking grandeur of the animals and visual effects. Some of the original silliness remained, unfortunately, in the later New York sequences once the cast and crew had returned for Kong’s exhibition on Broadway, and yet the touching poetry of Ann’s reunion with Kong atop an icy lake in Central Park, a sweet, somehow fragile wintry ballet, struck me as remarkably lovely in retrospect. However, the single element that had always impressed me was the final scene atop the Empire State Building in which the humbled denizen of a prehistoric era meets an excruciating assassination, his body riddled with stinging machine gun bullets, falling from nobility and grace to the littered streets below a stunning Manhattan skyline. Jackson had gotten this right from the outset…a sublime recreation of Kong’s final moments of tenderness within the gaze of Ann Darrow at the top of the world.

Upon a fourth viewing, this time on cable, I found myself…somewhat astonishingly… starting to love the film. Still later, Universal released an extended director’s cut of Jackson’s dream film, a three and a half hour restoration which incorporated some breathtaking sequences that should never have been eliminated from the film in the first place. I sat down in my living room at the time, cleared my mind of any misgivings or preconceptions, and watched Jackson’s King Kong for the fifth time. It was in many inexplicable ways, however, the “first time” that I had really seen it. My mind and heart raced back to December 14, 2005. I turned down the lights and felt the exhilaration I initially felt on opening night when the theatre lights first dimmed, and the Universal logo lit up the screen. Among the restored sequences was an exciting homage to the original production in which a malevolent stegosaurus crashes through the jungle brush to attack the intrepid explorers. As they fell the beast with rifle fire and gas bombs, the creature’s spiked tail rises and falls thunderously onto the jungle floor in poignant conquest, for this was, after all, a dinosaur…a prehistoric beast, a paleolithic echo from an earlier film.

However, the real treasure unearthed by the studio for this handsome, extended edition is, unequivocally, a lengthy and terrifying sequence in which fanged sea creatures from beneath the depths come flying out of the primordial mist to devour the defenseless sailors on a hastily constructed raft adrift upon the murky moat. It is a brilliantly realized scene and one of the most dazzling show pieces in the entire film. The new footage does much to flesh out an already impressive production, offering Kong what it might have subtly lacked in its original inception and release. A joyous revelation during subsequent viewings has also been a deeper appreciation of, and reverence for, James Newton Howard’s heart wrenching score for the film. While neither as bombastic as Max Steiner’s original composition, or John Barry’s somber requiem for the second film, Howard’s romantic tenderness, and poetic eloquence stand among the finest achievements of his deservedly respected career. In retrospect, Peter Jackson’s King Kong is an astonishing achievement, a breathtaking exploration of a world lost and hidden from the beginning of time. The deluxe DVD edition includes a handsome sculpture of the beloved simian climbing his final, tragic refuge in the clouds…the majestic Empire State Tower…a haunting remembrance of an unforgettable fable and finale.

While the casting of Jack Black in the pivotal role of Carl Denham remains mystifying, as does the ultimate trashing of Jack Driscoll, whose singular origins and portrayal by Bruce Cabot stand alone as the only major original cast member pointedly excluded from the loving acknowledgements in the final credits, this film grows more profoundly impressive with each successive viewing, and is a powerful and exhilarating re-imagining of a beloved fantasy classic from film making’s own primordial past.

++ Steve Vertlieb — November, 2014

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

“miles below”… like, a quarter of mile?

An enjoyable retrospective, but this definitely didn’t happen in the 1933 movie: “Their aged freighter, crashed cruelly against marauding waves, leaves them marooned on Skull Island…”

In King Kong (1933), they anchored their tramp steamer offshore, sent small boats to Skull Island, came back, the locals paddled up to the ship and kidnapped Ann, and the crew rowed back to the island, retrieved Ann, gas-bombed Kong, and built a giant raft to float him back to their ship, which was still intact.

And so I’m left side-eyeing all the other “facts” in these concatenated reviews. What else did the reviewer conflate, or just get wrong?

I plead guilty to a slightly over dramatized presentation.

One more: “Slaughtered by unforgiving machine gun bullets,” — no, it was beauty killed the beast.

bill: When you’re right — you’re right!

In actuality, Kong was killed by both Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack who machine gunned him to death in their airplane at the climax of the film.

Jackson’s “remake” of Kong was ludicrous.

Dinosaurs stampeding on the side of a cliff.

Kong swinging on vines while fighting not one, but three t-rexes.

Ann’s supremely silly relationship with Kong.

And the much anticipated but now distasteful spider pit sequence, where a sailor comes swinging on a vine with a machine gun to save the day.

The thing that most brought the original film to mind was the accurate recreation of the tramp steamer Venture.

All in all, very disappointing, especially considering Jackson’s fantastic work on the Lord of the Rings trilogy.