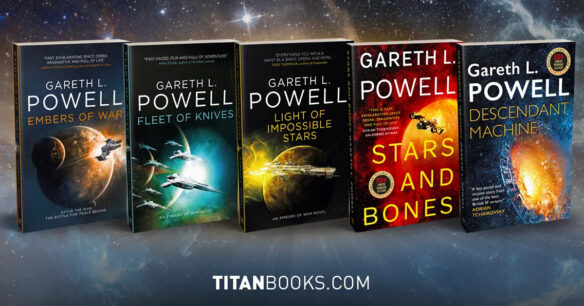

[Editor’s Note: Gareth Powell is a British SF writer who has written three series, to wit the Ack-Ack Macaque series with airships and cigar-smoking-monkey fighter pilots, and the Embers of War with ships akin to those in Iain M. Banks’ Culture series. Powell’s latest series is The Continuance in which all of humanity has been exiled from Earth and is wandering the galaxy in vast ark ships. The latest novel in that series, Descendant Machine, came out in May. Both the Ack-Ack Macaque and Embers of War series had novels in them that won British Science Fiction Society Awards. Keep up with Gareth L. Powell’s Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook via Linktree. And at his Substack: Gareth’s Newsletter. Cat Eldridge says, “You, Ian McDonald and Iain M. Banks are the best writers of space opera that there has ever been.”]

“I was attracted to science fiction because it was so wide open. I was able to do anything and there were no walls to hem you in and there was no human condition that you were stopped from examining.”

Octavia Butler

While I have been known to write other types of science fiction, there’s something about space opera that keeps drawing me back.

The term ‘space opera’ has been around since the heyday of the pulp magazines in the 1930s and 1940s. Initially the term was one of derision, likening the genre to tacky ‘horse opera’ westerns. However, just as the hippies and punks of the 1960s and 1970s took their derogatory labels and wore them with pride, so the term ‘space opera’ eventually became a byword for action-packed stories featuring big spaceships and weighty themes.

To date, I’ve written eleven novels, from Silversands (2010) through to Future’s Edge (coming 2025), and at least seven of them can be described as space opera. What is it that keeps bringing me back to the sub-genre?

At its best, space opera contrasts the personal with the cosmic. Human characters struggle against the backdrops of infinite space and deep time, wrestling to uncover the reasons why we’re here and what it all means. It gives us a vast canvas on which to make our points. As storytellers, we’re no longer confined to one world or one society. If we want to say something meaningful about the world of today, we can let our tales leap from culture to culture, shining a light on our real life existence by showcasing worlds that are very different in almost every respect.

When George Lucas wanted to write about a great democracy falling to fascism, he wrote Star Wars to dramatise his concerns; similarly, Iain M. Banks invented the Culture, a spacefaring, post-scarcity civilisation with utopian ideals in order to write a counterpoint to the politics of 1970s Britain; and Ursula K. Le Guin wrote her classic novel The Dispossessed to examine her feelings regarding the Vietnam War and the contrast between anarchy and capitalism.

Not all space operas are primarily political, of course, but there is that old maxim about all books being essentially about the time in which they’re written, and the very act of imagining societies different than our own cannot help but invite comparison. I certainly used books like Embers of War and Stars and Bones to comment on what I see as some of the absurdities of our current set-up in ways I possibly couldn’t have articulated in a more contemporary setting.

More than that, I think the appeal of space opera is that by placing relatable characters outside of the contexts with which we’re familiar, and contrasting them with non-human intelligences, you can really unpack what it means to be human in the unspeakable vastness of the universe.

As an author, it gives you the freedom to write whatever you want, in a cosmos where almost anything is possible.

But maybe what really appeals is the sense that in space opera, we’re all masters of our own destiny. We’re not bound by anything, save the need to keep our ship flying and stay one step ahead of our enemies and creditors. We go where we want and we do what we have to in order to survive. And we’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe. We’ve left footprints in the multi-coloured sands of a thousand deserts. Our faces have been tanned by the light of stars so far from here their light won’t reach this part of space for another hundred years. And we’re still questing outwards, still searching for adventure—for an alien invasion to repel or a repressive regime to overthrow. And, at the end of the day, we get to sit in our ships and look out the windows at the cold, distant stars and somehow make our peace with our place in the unending wonder of it all.

[Reprinted with permission.]

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Well, I’m that old that I still don’t like “space opera” as a label. To me, those are the stories with big themes… but written lightly, without a lot of deep thought, just taking things in our history, dressing them in fancy clothes, and renaming them.

What I’m writing, I prefer to call straight science fiction. I’m working on the stuff that drew me (and many others) to the genre originally. Feel free to read my first novel, 11,000 Years… and tell me I haven’t read, say, Stapledon and Clarke and others. My next novel that will be coming out later this year, sure, no problem, I admit I’m thinking of Brunner.