By James Bacon: On Friday July 6, 1934 the first issue of Greann, one of the earliest known Irish comic books, was released, published in Drogheda by Joseph Stanley and made available across the country.

1934 was a good year for comics internationally, with the debut of Alex Raymond’s Flash Gordon and Lee Falk and Fred Fredericks’ Mandrake the Magician by King Features Syndicate in US Sunday newspapers, and Famous Funnies #1 published by Eastern Color Printing, an early US comic, sold on newsstands in the format we now know.

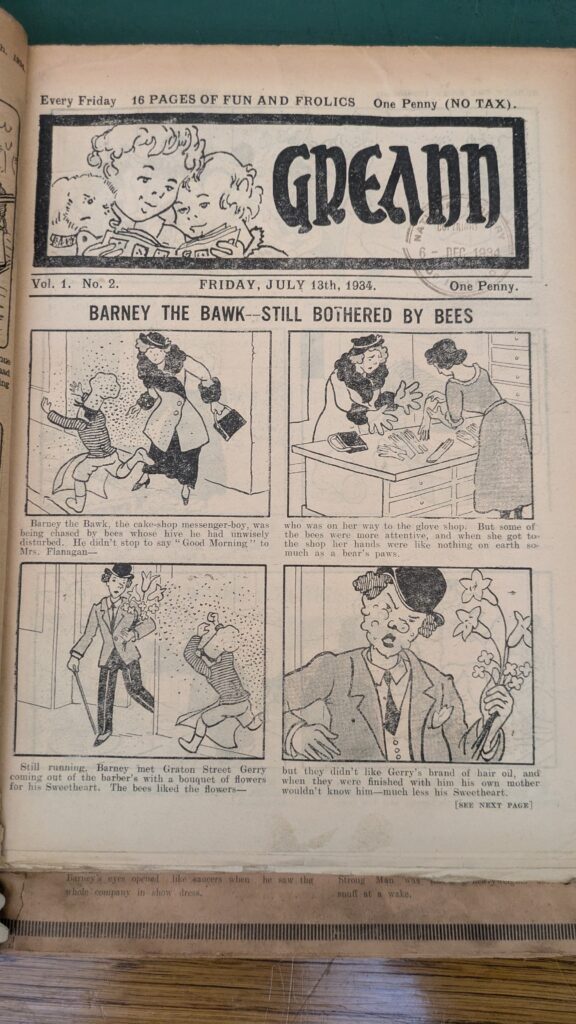

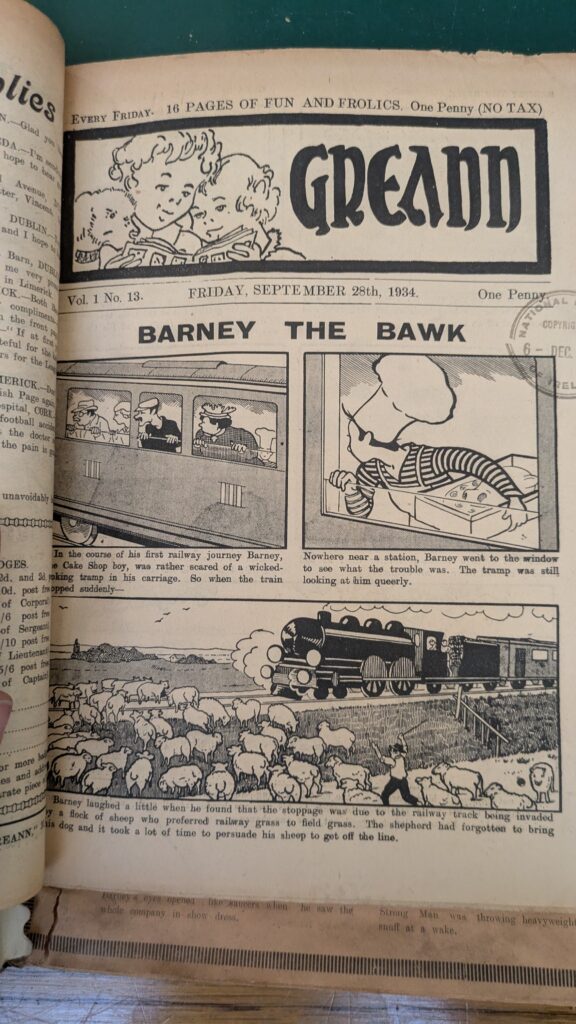

Into the widening world of comic books came Ireland’s own Greann. The simple masthead shows two children and a dog reading a comic next to the title, Greann. The editor Uncle Seamus soon tells us that “Greann is pronounced like the first half of Granny and is the Gaelic word for Fun.”

Barney the Bawk, an adventurous young baker, is the front cover text comic, and the sequential images have the narrative underneath them. The weekly sixteen-page black and white comic, released every Friday and costing One Penny (No Tax) contains a variety of text comic stories including:

- Barney the Bawk

- Bid’s Butterfly Bothers

- The Frightening Fate of Fergus the Face-Maker

- Taispeanann Luirgna Fad Do Seamus Conas Tomadh Do Deanaimh

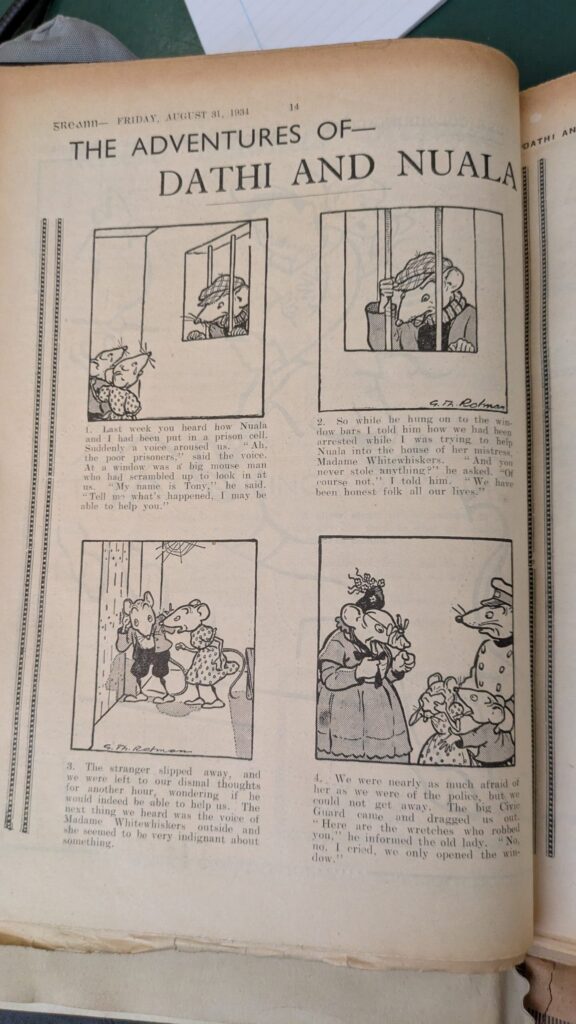

- The adventures of Daithi and Nuala a pair of anthropomorphic mice

- The Cats – whose adventures we follow.

These are children’s humorous stories of the time, simplistic fun, that present a full story. Some continue with fresh episodes each issue, others are one off. The single page “Taisbeánann Luirgne Fada do Sheámus Connus Tomadh do Dhéunamh” translates to “Long Shanks Shows Seamus how to Dive” and we see a youngster being shown how to dive, although it is to comic effect and it is in Sean Chló, the older typescript for Irish and credited to Doiminic mac Uidhir.

Included in each issue are a selection of puzzle challenges and entertainments such as:

- Can You Discover Where Our Crazy Artist Went Wrong?

- A Corner For Grown Ups

- Unfinished Drawing and Colouring Competition

We get a long editorial introduction from Uncle Seamus, which establishes an element of kindhearted fun and helps us understand the genesis of the comic and the editors’ mission:

UNCLE SEAMUS TO THE BOYS AND GIRLS OF IRELAND. HOW YOU CAME TO HAVE “GREANN.”

Some time ago I noticed a little Dublin boy looking into a newsagent’s shop window.

He was acting very strangely. First he would look in the window then he would go to the door and look into the shop. Back he would go to the window, go down on one knee and twist his head on one side in a funny way.

I went over to see what he was looking at. I found it was the front page of a comic picture paper that had fallen down and was lying crumpled up at the bottom of the window.

Why don’t you buy the paper?” I asked him “Then you could read it all”

He searched his pockets, all seven of them. At last he produced two half-pennies one of them from the lining in a far away corner of his coat

That’s all I have,” he said, “and they’re twopence now – with the tax” “I used to buy that one (pointing to the paper in the window) every week but sure I can’t now”

I gave him the extra penny and you should see how happy he was as he dashed into the shop and proudly demanded his favourite paper.

“Then and there, I decided that it ought to be possible to let Irish boys and girls have an Irish picture paper at a penny the same as and girls of other countries.”

“And that’s how you come to have GREANN. GREANN IS OUT FOR FUN”

This is quite a thoughtful introduction, demonstrating generosity and charity, but also mindful that foreign comics cost more, and that Irish children deserve an Irish newspaper at the same cost that English children would pay. The editors also remind the reader that “Greann (pronounced like the first half of Granny) is the Gaelic word for Fun – as I need scarcely tell most you who are learning Irish at School.”

This is clever stuff, clearly noting the cost – an issue relevant to many readers – as well as promoting national pride.

Reader engagement was always important with comics, and indeed, could change the direction and influence editorial decisions,and Uncle Seamus encouraged people to get in touch:

“WRITE TO UNCLE SEAMUS – So don’t be shy about sending me a little letter to say if you prefer Barney the Bawk letters to “Dathi and Nuala.”

There is the element of word-of-mouth as readers are asked:

And there’s another way you can help. Tell all your friends and playmates who may not have seen it about GREANN. Get them to buy it every week, and spread the news about it to their friends and playmates.” Uncle Seamus further presses the nationalist angle noting, “together-we can make GREANN better and better. And Irish children can have an Irish picture paper which they will be proud of as their very own.

Returning to the example of kindness, Uncle Seamus also mentions “that there are lots of little Irish boys and girls that haven’t even a penny to buy GREANN – and they’d love to read it just as much as you.” and he encourages children to be kindly, and generous, and suggests that “You can pass on your copy of GREANN to some boy or girl when you have finished with it.”

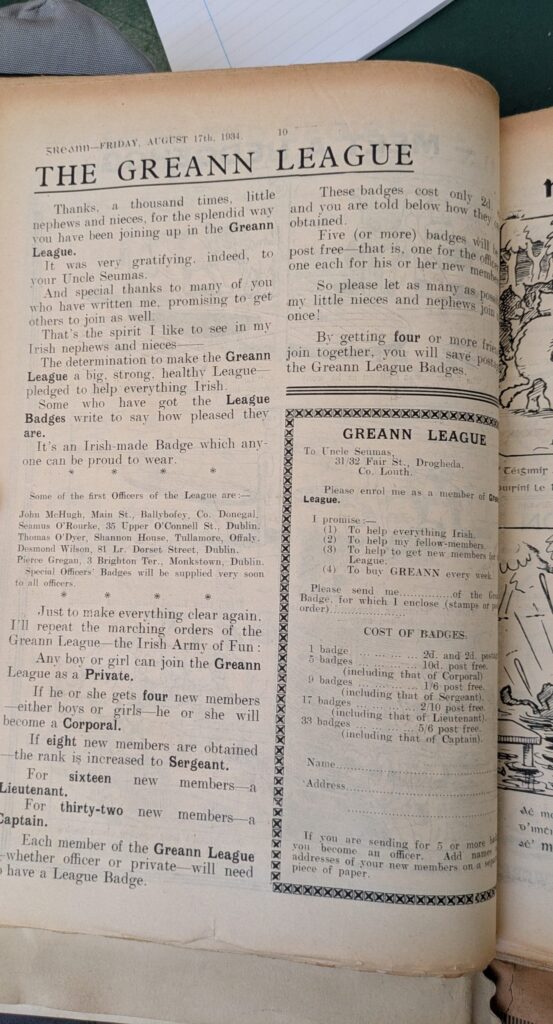

A contact address is supplied, and we see that post is welcomed to “Greann” 31/32 Fair St, Drogheda, with a telephone number of Drogheda 70, and printed by the Drogheda Independent, 9 Shop St, Drogheda.

In the second issue, we have some new stories, another single-page story as Gaeilge, “Dearmhad Bhráin” — Bran’s Mistake — by Sean Óg, “Mickey Gets Muddled” and “Sean’s Birthday Present.”

The seed that was sown in the first issue bears fruit and we see in issue 3 lists of winners of the picture painting and unfinished design competition with commendations, as well as a thank you editorial from Uncle Seamus.

In issue #4 we see a story as Gaeilge, which is problematic for a modern reader as it contains an outdated portrayal of a Black child and relies on skin colour for humour; “Páid Dubh Fiosrach – Inquisitive Black Patrick.” For clarity, the story follows the following structure and narrative:

We see a depiction of a black child walking, in football gear and the text tells us:

- Page 1: Inquisitive Páid is walking one day

- Page 2: He sees a ladder against a wall (with some builders scaffold)

- Page 3: He interfered with it, (we see a bag of white powder fall) and instead of being black he was white

- Page 4: He was sorry, but he learnt a lesson

- Page 5: He saw black things in a bag on the same day (might be coal)

- Page 6: He rubbed his face and hands with them, and now he is delighted.

An attempt at racial based humour that would be considered racist today. In a later issue Barney the Bawk is at a fancy dress in a “Red Indian” costume which is the cause of “humour” when he returns to work. There is also a “Cats” Story where they are playing games in old coal bags and all the cats end up being black and cannot tell the white cat Lilly apart from them.

Issue #6 sees that the mail has caught up with publications and we have a slew of Uncle Seamus replies and the launch of “The Greann League” with its own merchandise and badges. Subsequently offices of the League are opened, located wherever readers offer to host them.

I felt that the comic strips were imported, and sure enough we see that some of the stories are indeed reprints. “Moloney Falls” a stand-alone cartoon in #8, has the signature of A. G. Badert, who is Albert-Georges Badert, who at this time had been drawing illustrations for Parisiana.

In issue #9 we see that “Daithi and Nuala” is signed by G. Th. Rotman who was an early Dutch comic book artist. The Dutch comic book shop Lambiek notes that “Rotman’s first comic (then called a “picture-story”) was ‘Snuffelgraag en Knagelijntje,’ about the adventures of a brother and sister mouse, written by Arie Pleysier. It appeared in 1924 in the socialist periodical Voorwaarts, and soon became very popular.” The comic was translated into French and English.

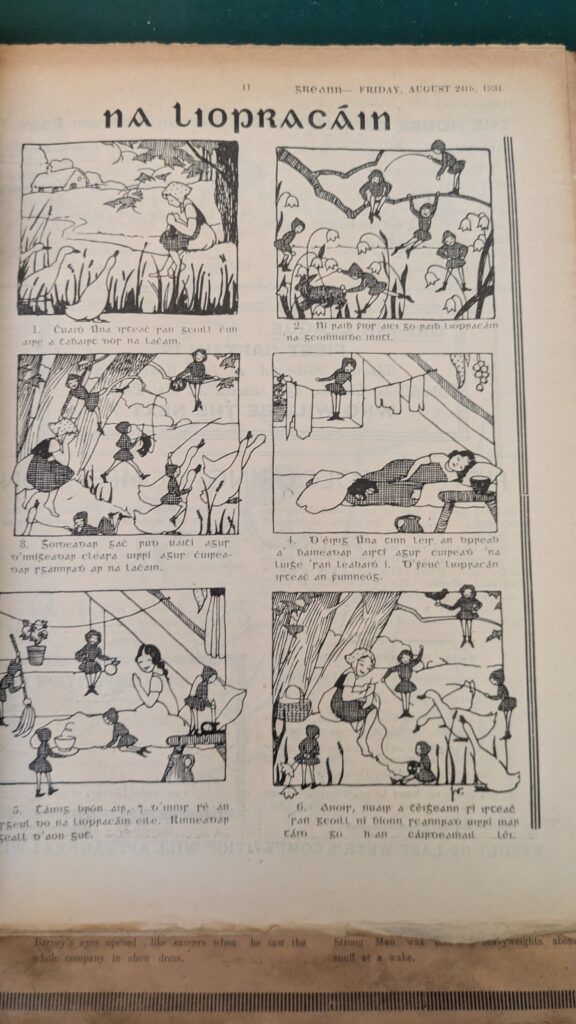

Irish elements permeate, so we get “Dan Donovan from Ballymacwhack”, and the prose story “The Monster of Lough Lurgan,” and “Na Liopracain,” while we also have the creation of Mad Meehaul the artist, who features as a humorous relief that is utilised to engage with children.

That the comic stories were coming from elsewhere is evident. In one issue, we see a group of anthropomorphic animals, Seamus, Sean and Saoirse, who are a regular strip in Greann, albeit, it started with just Seamus and Sean. The outline of speech bubbles is visible, and actually look like clouds, except in issue #10 where one set of words was missed, leaving a speech bubble with “moi!” in it.

By issue #17, children are being offered “over 200 pages of fun for a shilling,” in volume 1, number 1 to 13 collected and available for a shilling from “Greann” in Fair Street, Drogheda, or 1’2 by post.

The paper had changed in issue #15, and again in #18, being more pink and also larger, and now states “The Only Irish Comic” on its front page; this was still 1d on Friday, November 2, 1934.With this new format, some comics changed size, increasing, while others, such as Seamus, Sean and Saoirse, are centered allowing the page to be shared, and the margins containing the Uncle Seamus Replies, results of competitions and new league offices. Noticeably the increase in page dimensions brought a decrease in page count, and the comic is now only eight pages! Quite a reduction down from sixteen.

Issue #25 advertises Greann Christmas Cards, 12 for 6d, another method to generate income. But signs of trouble are there – fewer pages for the same amount, cheaper printing, etc.. Comic book readers know the signs, and indeed, on Friday 1st of March, 1935, Vol 3 issue #33 we get the sad news:

UNCLE SEAMUS TALKS – THIS IS LAST ISSUE OF GREANN.

Uncle Seamus is more sorry than he can say to announce the bad news to his nieces and nephews that this is the last issue of Greann. Uncle Seamus had earnestly hoped that it would have been possible to continue Greann as a fortnightly.

But unfortunately the sales have not been sufficient to meet the expenses of continuing our little paper. It is a great pity because Uncle Seamus is convinced that it would be better for Irish children if they had an Irish paper of their own.

To the many loyal nieces and nephews who supported Greann and the Greann League Uncle Seamus, sends his very best thanks: As he said before, it is not their fault that Greann cannot continue.

He has had so many letters from them expressing their sorrow that Greann was not being supported that it would be impossible to reply to them all. But each and everyone of them will always have a warm spot in the heart of

UNCLE SEAMUS

Bringing to an end – until we find an earlier one – Ireland’s first comic.

With thirty-three issues in all, these Vol. 1, issue 1 from the 6th of July, 1934, to Vol. 3, issue 33 March 1, 1935, are bound into a single volume in the National Library of Ireland. The first issue is incomplete, suffering some damage at some stage, but these comics are available to see and read, which is incredible.

The perennial issue of comic book printing and distribution, an issue continued today with the bankruptcy of Diamond Comics in 2025, triggered legal action being taken in the courts in 1934. This event offers considerable insight into the operation of Grann, as reported in the Drogheda Independent on Saturday the 22nd of December, 1934:

PRINTING ACCOUNT AND COUNTERCLAIM. Printing: of Irish Comic Weekly. Owen J. (Belton,. Receiver, and ‘The Examiner,’ Press Ltd., 68 Clanbrassil St., Dundalk, Printers, were plaintiffs and Joseph M. Stanley, Fair Street, Drogheda, Publisher, defendant in a civil bill for £17 15s. balance due for printing, work and labour done by plaintiffs.

This legal matter, while unfortunate, helps us understand a considerable amount about the publishers, as it centred on the printing and distribution of Greann. The issue at hand was that:

Defendant owed £17 15s. to the paper for the printing of “Greann” a weekly Irish comic for children as well as for letter-heads, certificates and things like that.

Joseph M. Stanley, Fair Street, Drogheda, brought a civil bill against Owen J. (Belton, Receiver, -and the ‘Examiner’ Press Ltd., Clanbrassil St., Dundalk, for £25 for damage for breach of contract… the defendants… contracted with the plaintiff to print weekly the issue of a paper called “Greann” and to deliver some in accordance with the plaintiff’s instructions. They failed to carry out these instructions with regard to issue number 3 of the said paper resulting in loss and damage to the plaintiff. The defendants without giving proper notice to the plaintiff refused to print issue number 10 of said paper resulting in loss and damage to the plaintiffs.

The Examiner was engaged to print the comic, but with issue No 3, things went wrong, being sent by rail as “returned News” instead of the correct form and “An incident like that would have a terrible effect on a new publication starting off and showed great negligence on the part of the ‘Examiner’ officials.”

Joseph Stanley, the plaintiff, swore he was proprietor of “Greann” which started publication in July of this year. Number 2 issue was the first one printed by the “Examiner.” The “copy” was to be supplied on a Thursday and the paper was to have been printed and delivered to the wholesalers on the following Tuesday. There might have been a little latitude until Wednesday morning. The paper was then sold to the children on Friday. The papers were to have been dispatched by the quickest service which would obviously be by passenger train to places like Limerick, Cork, Galway and Belfast.

Returned news is a cheaper rate of transportation, and also less prompt, and Stanley had to pay the difference, and there was subsequently an issue with number 4 which was about to go by goods train only for an intervention. The court reporting includes some sales data:

In the number 3 issue there were 6,500 copies printed and the returns were 3,140. Fifty per cent of the issue was unsold as a result of the late delivery. This would, of course, affect the subsequent sales of a newspaper especially when the readers were children. It lies largely with the wholesalers to make or mar a paper and wholesalers having the impression that Irish publishers do not keep to schedule, he was trying from the beginning to disabuse that idea by keeping to schedule.

We also learned that “Mr. Stanley said that he had a paper in Dublin known as the ‘Gaelic Press’ That had been broken up 3 or 4 times and witness suffered a loss of £3,000 or £4,000. He then got into a libel action and was driven into the bankruptcy Court.”

This is a stunning connection. The Gaelic Press was a nationalist press and this means we are dealing with Joe Stanley, who was Padraic Pearse’s press officer during the 1916 Rising. Another issue with Greann was the cancellation of printing, and the clarity of communication and instructions, and there seems to have been some issue in regard to transportation between printers and railway:

The Justice then reviewed the evidence and gave a decree in the second civil bill, Stanley v. Examiner Press, for £12 10s. In the first civil bill, Examiner Press v. Stanley a decree by consent was given for the full amount sued for. viz., £17 15s.

Joseph M. Stanley had made mention of owning the “Gaelic Press,” which was a radical publishing company established on Liffey St in Dublin and it printed many of the 1916 Rising documents, including the Proclamation of Independence and the Irish War News. Stanley was himself a Republican activist.

The witness statement of Capt. Sean Prendergast Captain of the Dublin Brigade Irish Volunteers shared details:

Joseph Stanley, proprietor of the “Gaelic Press”, been interned in Frongoch after Easter Week” he continues “Joe Stanley, through his printing press had and was rendering important service to the republican cause in turning important out seditious literature and publications, song sheets and pamphlets, and because of that was not very much in the good graces of the Dublin Castle Authorities. Joe Stanley was proprietor of the “Gaelic Press”, Upper Liffey st and its printing establishment in Proby’s Lane adjacent thereto. He also carried on a shop “The Art Depot” in Mary Street for the sale of Irish literature, publications, photographs, song sheets etc.”

That shop was raided by police on Castle orders on at least one occasion…Joe became almost one of the first recruits to the auxiliary unit attached to our Company…

After release from Frongoch, Joe Stanley was promoted to Lieutenant in September 1917 as confirmed by Capt Prenderghast; “Joe Stanley joined the became at a later date a Lieutenant of “H” Company.”

Joe Stanley was a volunteer and a press officer to Padraic Pearse, he travelled to and delivered printed items to the GPO during the Easter Rising. Joe Stanley said “this work involved my attendance at the GPO for two or three hours each day on Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday in addition to dangerous penetrations through the British corr dons which were drawing in around the Post Office from Wednesday.” (Joe Stanley Printer To The Rising by Tony Reily, page 47). Pearse also handed Joe a letter for his mother.

Joe Stanley wrote later that “one month from the Rising of 1916 my printing plant valued at over £2,000 was dismantled and removed to Dublin Castle…two and a half years later, nearly £5,000 worth of plant and machinery was again seized and removed under similar circumstances.” The full correspondence is published in Riley’s book.

That such a person is subsequently the publisher of Greann is quite astonishing.

In 1929, Stanley moved to London, to work as a Sub-Editor for the Daily Mail, while supporting the family in Hacketts Cross, Clogherhead. The cinema business was managing itself, and he desired to earn money and seems to have been a determined entrepreneur. At this time Greann came to mind. An image of an October issue of Greann and a mention of the comic appear in Tony Reilly’s excellent book on page 171 and 172: “Joe spent the following six years in London. Even from that distance, he tried another business venture when he started one of the earliest Irish comics. He called it An Greann (The Fun), but it had limited success.”

It is notable in the court case, that he at one stage stated he had to go to London, so he must have delegated a considerable amount of the tasks of Greann to others, which is quite an accomplishment. Joe Stanley went on to purchase the Drogheda Argus and Advertiser and again according to Riley “restored it to its former glory, assembled a staff and was soon operating from the original Argus premises at 6 Peter Street, Drogheda. He was up and running in the printing business again. He pushed ever onward and soon added the Monaghan Argus to his publication portfolio, and his printing empire began to blossom once again.”

31/32 Fair St as advertised in Greann seems to have been at the time of publication the Boyne Cinema, which makes total sense. Riley notes that the Drogheda Independent reported on the January 27, 1919, that the cinema was under “Irish-Ireland management” belonging to Joe Stanley. Controversy was to follow soon enough with the showing of “The Sinn Fein Review” on the 14th, 15th and 16th of April, with British forces raiding the cinema on the 16th of April.

This building has a fascinating history, starting as St Mark’s Church, then Hall, then becoming the St Oliver Plunkett Hall, then Picture Palace in 1910, and Boyne Cinema in 1919. David Clougher wrote a superb article on the history of the building.

Joe Stanley had a garden named after him in 2016. As the Meath Chronicle reported on Thursday April 21, 2016: “The Garden is named after Drogheda native, Captain Joe Stanley, a former Alderman of Drogheda Corporation. He served as Press Agent to Pádraig Pearse during Easter Week at the GPO. He printed the first documents of the newly proclaimed Republic: the iconic Irish War News along with the Proclamation to the Citizens of Dublin and The Irish War Bulletin 3. These were the only documents issued by the leaders from the GPO during Easter Week.”

That Ireland’s first comic was published by someone as singularly fascinating as Joseph Stanely, who had such a varied and crucial part in Irish history himself through his publishing, is amazing.

Notes, links

Images of Greann reproduced with permission of the National Library of Ireland.

I am indebted to the staff at the National Library of Ireland, where a lovely bound volume of these comics exists for all to enjoy. My thanks to Frances Clarke, Nikki Ralston and Sinead McCoole for support and all those at the Library who have helped with research.

The collected and bound volume of Greann is in the National Library of Ireland: Holdings: Greann. (nli.ie)

Uncle Seamus is spelled “Seumas” in the early volumes and it switches to Seamus, we spelt it “Seamus” in all cases here, taking it to be an early error.

The Drogheda Independent Saturday December 22, 1934 reported on the court case.

Joe Stanley: Printer to the Rising. Brandon Books, DINGLE, 2005 by Tom Reilly

Lambiek Comiclopedia has been invaluable for sourcing information on European artists.

Websites about The Boyne Cinema

- https://earlyirishcinema.com/category/picture-houses/boyne-cinema-drogheda/

- https://theirishantiquarian.substack.com/p/the-lost-church-of-st-mark-drogheda

- https://cinematreasures.org/theaters/55035

Links of Interest about Joe Stanley

- https://joestanleygaelicpress.com/

- https://gaelicpress.wordpress.com/information-on-the-book/

- https://www.meathchronicle.ie/2016/04/21/drogheda-to-remember-pearses-press-agent-joe-stanley/

Joe Stanley Printer to the Rising by Tom Reily from Bandon Press is an excellent read.

WS Ref #: 755 , Witness: Sean Prendergast, Member Fianna Eireann, 1911; Officer IV, Dublin, 1914 – 1916; Captain IRA, Dublin, 1921 https://www.militaryarchives.ie/en/online-collections/bureau-of-military-history-1913-1921/witnesses

Many thanks to Pádraig Ó Méalóid for his assistance with the translation of séan chló, agus Allison Hartman Adams. Photos of Fair St by James Shields with thanks.

James Bacon found himself reading Greann while conducting research for his forthcoming book Rebellion, Nazi Spies and the Troubles; Irish Conflict in 20th Century Comics and welcomes any information on this subject, Irish Horror Comics, early Irish comic book publications, and welcomes corrections and correspondence to irishconflictincomics at gmail dot com.

A Companion article “The Leprechaun, and the Irish War on Comics” appears on Down the Tubes.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Pingback: The Leprechaun, and the Irish War on Comics – downthetubes.net

Excellent. Wonderful. Thanks for posting this, James!

How marvelous to read this just before the Feast of St. Patrick!

But what/where/who is Down the Tubes?

Pingback: The Story of “Greann”, Ireland’s First Comic Book – from a veteran of the 1916 Rising – downthetubes.net