By Lee Weinstein: My wife, Diane, and I traveled to the UK in late summer of 1995 to attend the World Science Fiction Convention in Glasgow. Along the way, both before and after the Worldcon, we stopped at a number of places that we wanted to see in person. We visited Loch Ness; Findhorn; Glamis Castle, allegedly once the home of a deformed heir, hidden away in a secret room; and Portmeirion in Wales, where the surreal Sixties TV series, The Prisoner, was filmed. Our last stop on the three-week journey was several days in London, and while we were there I decided to act on another idea percolating in the back of my head. I had discovered the village of Biddenden was only about 50 miles from London and I decided to go there on our last day. This village of about 2500 people, situated in Kent in southeastern England, was supposed to be the birthplace and home of a legendary pair of conjoined twins.

I had come across the story of the Biddenden Maids, as the twins are generally known, in numerous places over the years, including Gould and Pyle’s Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine (1896), C.J.S. Thompson’s The Mystery and Lore of Monsters (1930) and Frederick Drimmer’s Very Special People (1973), with texts often illustrated with stylized woodcuts of them.

Conjoined twins have always attracted a lot of attention throughout history, but the Maids have been cited as being one of the very earliest examples known to medical history, having been born in the year 1100 CE. According to the accounts, they had willed 20 acres of farmland to the village, the “bread and cheese lands,” which were to pay for the annual distribution of bread, and cheese, as well as small biscuits, imprinted with their image, every Easter Monday. I had seen one of these tan biscuits on display in Philadelphia’s Mutter Museum a few years earlier. It appeared to be quite hard and inedible.

I bore in mind that the Maids had been born in the 12th century and the books reporting their story were specialized volumes on human oddities. I wondered if the charity founded in their name was still ongoing and the imprinted biscuits were still being made, or if it was all ancient history. But I was very curious. Because Biddenden was only a little over an hour away from London and easily reachable by train and bus it was feasible to take a chance and find out. If nothing else, I could see the village where they had lived.

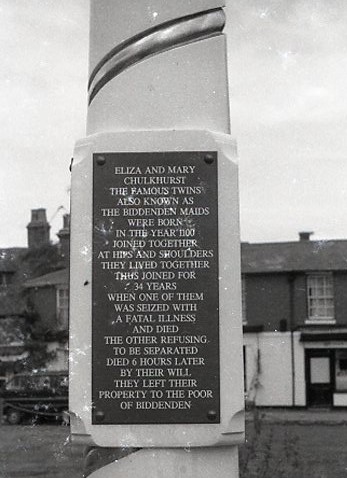

My wife decided to stay behind and explore London’s National Portrait Gallery while I went on. It was a warm cloudy day at the beginning of September as I headed across Trafalgar Square and into Charing Cross Station. The train I boarded, I recall, had multiple doors along the sides, each compartment being separate from the others and accessible only from the outside. After a pleasant hour or so that afternoon, rolling through the green English countryside, I reached Headcorn station, where I transferred to a bus for the remaining four and a half miles of the journey. I wasn’t sure what to expect. At Glamis Castle the tour guide seemed to know nothing of the legendary deformed heir hidden in a secret room. Would there be anything here at this late date about the conjoined Maids? But when I disembarked from the bus, that summer afternoon, I was surprised to see, at the junction of the main street with the highway, a tall signpost topped with a stylized emblem of the conjoined sisters. This image, which had appeared in variant versions in the different sources I had seen, showed two women standing side by side, seemingly attached to each other. Lower down, at eye level on the pole, was a plaque which briefly told the story.

It read, “Eliza and Mary Chulkhurst, the famous twins, also known as the Biddenden Maids, were born in the year 1100, joined together at the hips and shoulders. They lived together thus joined for 34 years when one of them was then seized with a fatal illness and died. The other, refusing to be separated, died 6 hours later. By their will they left their property to the poor of Biddenden.”

I followed the main street into the quiet village, and passed a historical-looking inn and several shops. The tower of the village church was visible a little further down. I learned of a locally published pamphlet, The Story of Biddenden (1989), which had been carried at a shop called the Newsbox, but unfortunately, they were sold out. They did have postcards, however and I bought a few.

I stopped for a quick lunch at a combination tearoom and gift shop, where I ordered a “Ploughman’s Lunch,” consisting largely of bread and cheese. It didn’t occur to me until much later that bread and cheese were also what were distributed every Easter.

After lunch I continued down the main street, “High Street,” and headed for the tall castellated tower of All Saints Church.

The church, a brownish stone edifice which dates back to the 1200’s, was where, in previous times, the bread, cheese, and imprinted biscuits had been given out, until the end of the 19th century. The annual Easter Monday distribution was then relocated to another building, now called the White House.

The cool interior of the church contrasted to the late summer air as I entered, and encountered a white-haired gentleman who worked there. I told him I was interested in the story of the Maids, and he replied that there had been a Swedish researcher, a doctor, there a year or so earlier who was also investigating the legend. I hadn’t quite realized it, but there had been serious questions over the years about the truth behind the story. He went on to tell me that this researcher had written an article about his findings which had been published in a journal. He had a copy of the article, which he wanted to show me, but unfortunately didn’t have it at hand. He apologized and said if I gave him my address he would mail me the information. I wrote it down for him, and purchased a copy of the pamphlet I’d learned of, which told the story of the village. While he didn’t have any of the biscuits, he did have replicas of an old broadside about the Maids, and I shot a couple of photos of the inside and outside of the church.

My next stop, on the way back toward the highway, was an antique shop. I stepped in, hoping to find some further historical information and perhaps even one of the souvenir biscuits.

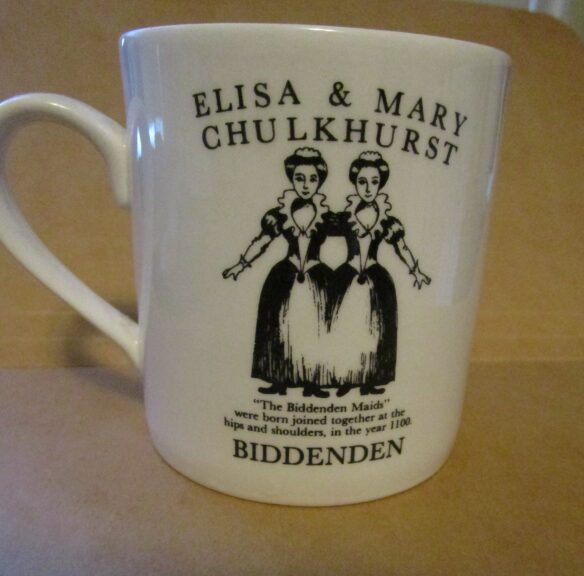

The proprietor was also an older man, who regretted he didn’t have any of the biscuits for sale —- they are given out during Easter, and this was September. However, he did have mugs imprinted with the stylized image of the Maids. He told me he had had them made up as a way to uphold the local tradition. He affirmed that the sisters had been born attached to each other. “Poor dears,” he sighed, and also mentioned the Swedish doctor who had been there previously. I thanked him, and bought a new souvenir mug for five pounds. While he didn’t have any of the imprinted biscuits for sale, he said he might be able to show me one. Unfortunately, my time was running short and I realized I would have to run to catch the bus back to the train station. The mug made a better keepsake anyway. I headed back to London to meet my wife in the National Portrait Gallery.

We returned to Philadelphia the next day and it was about a week or two later that I received a thick envelope in the mail with a return address in the UK.

It was from the gentleman I had met in the All Saints Church. I had nearly forgotten about it, but, surprisingly, he had followed through on his promise. A handwritten note with the copy of the research article explained that his copy machine wasn’t working and the enclosed copy was the only one he had —- and could I please return it. I was a little taken aback that he had sent me his only copy but was glad he had.

I read the article, copied from a medical journal, and the author, a doctor, explored the story of the Chulkhurst twins in some depth.

As with the deformed heir of Glamis castle, there were questions about the existence of the Chulkhurst twins. Some skeptical historians had suggested they had been merely ordinary sisters who had left money to the village, and the image of them standing side by side had become corrupted over time so they appeared to be conjoined. Some skeptics had even suggested that they never existed and the story had been invented, possibly in the 16th or 17th century, to explain the annual tradition of bread, cheese and biscuits. It is true that the name Chulkhurst doesn’t appear until the 17th century and was apparently a later invention.

The findings in the research paper, however, which had been published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine in 1992, did not agree. The author noted that mentions of conjoined twins in the historical records of the 16th and 17th centuries, were conspicuous by their absence. On the other hand, there were several historical records of such births in and around the year 1100. There were also descriptions in several English chronicles of a pair of female conjoined twins, joined from the breast to the navel, who were born either in 1099, 1100, or 1103, depending on which chronicle was being consulted. None exactly matched the traditional description of the Maids but it showed that they attracted attention at that time.

As for the charity, while extant records traced it only as far back as the 17th century, the earliest records indicated it was already a long-standing tradition at that time.

Finally, while twins conjoined at two places as described is not medically feasible, it is quite possible they had been joined at the hip, a common area of attachment for such twins. It had been suggested by others that if they had been attached at the hip, they would likely have habitually put their arms around each other for physical support. Due to stylization over time, later depictions of them might have led to the belief they were also attached at the shoulders. It was quite possible they had survived for 34 years and that one could have outlived the other by six hours. There are known examples of conjoined twins who have lived much longer and who died hours apart.

The final conclusion drawn from all this was that the legend could very well have been based in reality.

Having read the paper, I made a copy for myself and mailed the original back to its owner, thanking him profusely and telling him he really needn’t have sent along his only copy.

In 2000 I found a newly published book called The Two-Headed Boy and Other Medical Marvels by Dr. Jan Bondeson which shed some further light on the subject. I had already bought and read a fascinating book of his a few years earlier called A Cabinet of Medical Curiosities (1997) which covered such subjects as giants, people with tails, the theory of maternal impression, and spontaneous human combustion.

This new book contained a chapter on the Biddenden Maids. After reading it I dug up the photocopied article I had, took a look and got another surprise. The Swedish author of that 1992 paper, unfamiliar to me at the time, was the same Dr. Jan Bondeson.

In the book, he added material that hadn’t appeared in the journal article, such as a twelfth century poem about conjoined English girls with separate upper bodies who shared two legs between them.

The discovery inspired me to reach out and contact Dr. Bondeson. I managed to find his email address online and sent him a note explaining I had been in Biddenden in 1995, and had heard about the Swedish doctor who had preceded me there.

He responded, thanked me for contacting him, and mailed me copies of several of the original papers that he later had adapted into his books.

Although Dr. Bondeson had not found absolute proof of the existence of the Maids, he did find enough circumstantial evidence to suggest that the legend indeed had a basis in fact. The charity in their name continues to the present day. And the mug bearing their image sits in my living room curio cabinet.

Lee Weinstein’s website: https://leestein2003.wordpress.com/

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

For interest, (Dr.) Jan Bondeson is a frequent columnist in the monthly magazine Fortean Times. This month’s issue (FT437 November 2023), which I happened to purchase yesterday, features #39 The Blundellsands Hermit in his regular series ‘Peculiar Postcards’, and a separate article in the ‘Forum’ section, Pursued by ghosts: my haunted houses, which is featured on the cover with a suitably eerie photo of the author.

A ploughman’s lunch, traditionally, is a loaf of bread, a chunk of chees, and a pickle.

Fascinating. Thanks.

Additional historical and modern conjoined twins:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chang_and_Eng_Bunker

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abby_and_Brittany_Hensel

One more thing – back then, if they weren’t wealthy, the odds on them having a last name, rather than just “daughter of so-and-so” are slim

Thanks for this article. It opens new windows on the past for me.