By Lee Weinstein: I first encountered the Elephant Man in a worn-looking old medical book in the stacks of the Jefferson Medical College’s library in Philadelphia. The year was 1964, I was a teenage student participating in a summer program there, and the Elephant Man was unknown then to the public. While exploring the old library, then in the basement of the research building, a title caught my attention. It was Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine, an over 900-page encyclopedic collection of strange, rare and unusual medical conditions. It had been compiled by two Philadelphia physicians, Drs. George M. Gould and Walter L.Pyle in 1896. The sounds of traffic rumbling by on Walnut Street filtered through the windows above, while I leafed through the many strange cases and grotesque illustrations. Under the heading “Anomalous Skin-Diseases,” I found a description of the horribly deformed “Elephant Man”, accompanied by detailed illustrations. The book was fascinating, but I put it on the back burner as I went on to complete high school and enter college as a biology major. I didn’t think about it again until the early 1970’s, when I saw a book in Penn’s Van Pelt library that piqued my curiosity. The title, The Elephant Man, rang a bell and I pulled it out and opened it. The title indeed referred to the same Elephant Man I had read of years earlier and nearly forgotten. The full title was The Elephant Man and Other Reminiscences (1923), and it was the collected memoirs of Dr. Frederick Treves about his little-known patients.

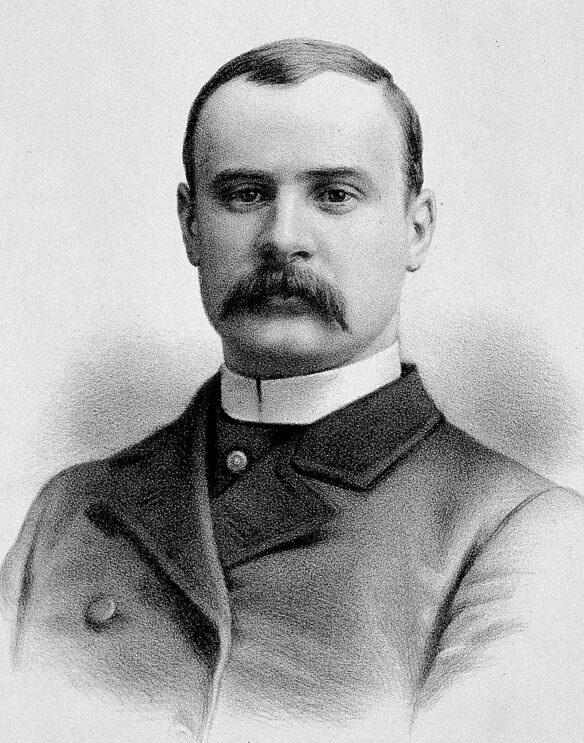

Dr. Treves was notable in his own time as a royal physician. In 1900 he was appointed to be one of the Surgeons Extraordinary to Queen Victoria and after her death in 1901 he was appointed to be an Honorary Serjeants Surgeon to Edward VII. But toward the end of his life he wanted to write about the common people he had treated over the years.

I sat down and read the title essay, in which Treves relates how he first met the Elephant Man, whose real name he gives as John Merrick, in November of 1884 who was being exhibited in a Whitechapel storefront. He recounts how he later rescues him from a London train station after his abandonment by his manager in 1886 and with the support of Francis Carr-Gomm, chairman of the hospital, makes him a permanent resident of the London Hospital for the rest of his short life. It was an engaging and well-written memoir and it told a fascinating story. While the information in Anomalies and Curiosities was brief and factual, this read like a short story, ending with Merrick’s tragic death at the age of 27 in 1890. It struck me at the time that it could be adapted and perhaps filmed. Treves’s essay, besides conveying the horrific consequences of Merrick’s disorder, brings the truly human side of Merrick to life, his intelligence and his emotional make-up. Little did I know the essay had already been included in three anthologies of horror fiction, The Fourth Pan Book of Horror Stories (1963), edited by Herbert van Thal, Strange Beasts and Unnatural Monsters (1968) edited by Philip Van Doren Stern, and A Walk with the Beast (1969) edited by Charles M. Collins. It was later anthologized in The Elephant Man and Other Freaks (1980) edited by Peter Haining. Another essay from Treve’s collection, “The Idol with Hands of Clay” has also appeared in horror anthologies, including And the Darkness Falls (1946) edited by Boris Karloff, and Wake Up Screaming (1967) edited by Lee Wright.

But it is the title essay that shows Treves at his most compassionate.

Not long after my discovery of Treves’s collection of memoirs, I found another book titled The Elephant Man (1971) in my local public library. This one was subtitled A Study in Human Dignity and was written by noted anthropologist Ashley Montagu. According to Montagu’s preface to the second edition (1979) Treves’s book had become a great rarity. I hadn’t realized how lucky I was to have come across it in the University of Pennsylvania’s library. Montagu also notes that it was the 1971 edition of his own book that inspired the various adaptations of the story that had blossomed in the late 1970’s. In it he reprints Treve’s original essay and offers his analysis of Merrick’s psyche. He gives Merrick’s full name as John Thomas Merrick and deduces from the available evidence that the cause of his deformities was von Recklinghausen’s disease or neurofibromatosis, a genetic disorder causing multiple tumors of the nerves and skin. But Montagu’s basic thesis was that because Merrick had a loving mother during his first few years, he was able to endure and rise above the extreme hardship that defined the rest of his life.

It wasn’t until 1986 that Montagu’s posthumous diagnosis of neurofibromatosis was challenged by Tibble and Cohen, Canadian geneticists who argued that Merrick more likely had an extremely rare condition called Proteus syndrome which wasn’t recognized as an entity until 1979. It results in overgrowth of the bones and overlying tissues, often on one side of the body.

This diagnosis has become generally accepted today.

Meanwhile, in the late 1970’s, a theatrical version of the story by a local playwright appeared in Philadelphia. The actor portraying Merrick remained masked for the entire performance.

Around the same time, the well-known play by Bernard Pomerantz began a run on Broadway lasting from 1979 to 1981. The actor used no makeup. The character’s disabilities were only suggested. When it ran in Philadelphia it was performed at the Forrest Theater, just a few blocks from Jefferson Medical College where I had first encountered Mr. Merrick.

In 1980 a new book on the subject, The True History of the Elephant Man, by Michael Howell and Peter Ford was published. It was thoroughly researched and the authors corrected a basic error. They discovered Merrick’s actual name was Joseph Carey Merrick. It is unclear why he was referred to as “John” by Treves, but that error persisted until 1980. Subsequent editions of this book appeared in 1982 and 1993 and 2011.

In 1980, David Lynch’s first studio film, The Elephant Man, was released to much critical acclaim. John Hurt, in full makeup, played the title role. Three years after the release of his low-budget cult film, Eraserhead, it launched Lynch’s career as a major filmmaker. It received eight Academy Award nominations and was novelized in the same year by Christine Sparks.

Although it didn’t win in any category, the nominations resulted in Best Make-up and Hair Styling becoming a new Oscar category in 1981.

With plays, a film and recent books about him making the rounds, the subject of the Elephant Man was therefore much in the air in 1982 when I was invited to visit friends in London. I’ve always made it a point, while traveling, to visit places and things I’ve read about. In the 1970’s while on the West Coast, I went out of my way to visit, among other things, the “Oregon Vortex” which I had read about in Stranger than Science, and Bryce Canyon and the Skunk Railroad, which I had discovered in National Geographic from 1958.

Similarly, during my nine days in London, I visited Leeds Castle, Madame Tussaud’s wax museum, the British Museum, Stonehenge, and a Shakespeare play performed in Regent’s Park, among other things. But also firmly on my agenda was a plan to visit London Hospital in East London’s Whitechapel district where Merrick had spent his last years.

Here, in London, was a chance to see in person what Dr. Treves had written about. In particular, I had read that Merrick’s skeleton was preserved in the hospital’s museum along with other related artifacts.

Not long after my arrival I took the Underground to the district of Whitechapel in London’s East End ( also the site of the Jack the Ripper murders, in the late 1880’s). The tall brick-faced edifice of London Hospital stood on Whitechapel Road across from the row of shops Treves had described.

I entered and told the receptionist I was interested in seeing the medical museum there. After a moment of slight discomfiture she replied I would have to make an appointment with the curator. She gave me his phone number and told me to call him in a day or two.

A day or two later, between other sightseeing adventures, I pulled out the curator’s phone number and rang him up from my friend’s home.

When he answered, I told him I was interested in seeing the hospital’s museum.

I heard a deep sigh. “The Elephant Man?” he asked in a resigned tone that told me I was far from the first person to ask him this

I stammered out that I was visiting from Philadelphia and while I admitted I did want to see the Elephant Man I was also interested in the other exhibits the museum had to offer.

“No, no.” he replied. I’m afraid not. There’s been entirely too much publicity.”

And that was it. I had no real credentials and he didn’t sound like the sort of fellow who would be willing to bend the rules. It was difficult for me to understand why he would shun publicity. Wasn’t the museum there to educate the public? Perhaps if I had been there a few years earlier it wouldn’t have been a problem. But considering Michael Jackson’s attempt to buy the skeleton in 1987, I can’t be entirely unsympathetic to the curator’s viewpoint.

I was disappointed, but nonetheless took some time to explore several bookshops in London’s Charing Cross district to find a copy of Treve’s book, but came out empty-handed. Surprisingly, no one had it.

But I went back to Whitechapel a few days later. In a small bookshop near the hospital I finally found a copy of Treves’s book, a recent paperback edition. Directly across the road was, as previously noted, the line of small shops Treves had described, still bustling with activity. I had with me the address of the vacant shop where Merrick was exhibited in 1888. Originally 123 Whitechapel Rd., the address was now number 259, according to Howell and Ford’s book. I crossed the road and discovered it was currently the home of a cheese shop. I went in, bought some cheese and asked the girl behind the counter, “Did you know this was where the Elephant Man was once exhibited?”

She shook her head with a blank look that told me she had no idea what I was talking about.

While I didn’t get to see the museum, I had seen the hospital and the environs that Treves had described. After leaving the shop I headed for Liverpool Street station where Merrick had returned to London in 1886. There was, of course, no longer a third class waiting room as in Merrick’s day, but the station looked much as it had in those days. And I had a copy of Treves’s book. Later on I also found many of his other essays to be of interest. “The Idol with Hands of Clay” was a moving and tragic story about a surgeon he knew, and in “A Restless Night,” he relates a nightmare he had in India about a patient, which, in my opinion, also deserves to be anthologized as a horror story.

Interest in Merrick didn’t die away. In 1985, another book on him was written by Frederick Drimmer, the author of Very Special People, and as noted, the book by Howell and Ford was reprinted several times. A graphic novel by Greg Houston, very loosely based on Merrick, was published in 2010 and a book on him by Norwegian-Italian author Mariangela Di Fiore was published in 2015.

Today, the seemingly obscure book I saw in 1964, Anomalies and Curiosities of Medicine, remains in print. It may have been in print since 1896. Treves’s collection of memoirs is also currently in print and Lynch’s film can be seen on DVD.

The museum of the Royal London Hospital, as it is now called, was eventually opened to the public some years after my trip there and remained open until 2020. The displays, including a replica of Merrick’s cap and mask, have since been moved to the museum in St. Bartholomew’s Hospital, three miles west. The actual skeleton remains within the London Hospital for the medical students.

I made a return trip to London in 1995, but didn’t make another attempt to see the museum at that time. I had become more interested in seeing the village of Biddenden, the home of the first reported pair of conjoined twins.

But that is a tale for another time.

Lee Weinstein’s website: https://leestein2003.wordpress.com/

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Very interesting – thanks for sharing this essay.

My favourite version of THE ELEPHANT MAN that I saw was a taped stage version that was televised back in 1982 starring Philip Anglim.

The details of this article are very interesting. It’s good to know that finally the Elephant Man’s true name and condition are recognized after all these years. Maybe if you get a chance to try again to visit the London Hospital they will have some means of getting a look. Best wishes.