INTRODUCTION: Eight Light Minutes(8LM) Culture of Chengdu has given permission for File 770 to reprint the series of interviews with Chinese science fiction writers which they have been running this week on Facebook. The first one is a question and answer session with Wang Jinkang, whose novella Seeds of Mercury is a 2024 Hugo Award finalist.

SUPPORTING CHINESE WRITERS SERIES (1): 2024 HUGO AWARD NOMINATION INTERVIEW WITH WANG JINKANG

Translated by Joseph Brant.

Wang Jinkang(王晋康) was born in Nanyang, Henan Province in 1948. He is a senior engineer, and a member of the Chinese Writer’s Association (CWA), The China Popular Science Writing Association (CPSWA), The Committee of Scientific Literature and Art, and the Henan Writers’ Association. Since the publication of his first story, The Return of Adam, in 1993, he has published over 90 short works, and 20 full novels, including Cross, We Together, Escape from The Mother Universe, Parents of Heaven and Earth, and Cosmic Crystal Eggs, totaling over six million words. He has won China’s Galaxy Award 16 times, as well as The Chinese Science Fiction Nebula’s Lifetime Achievement Award. He is considered one of Chinese science fiction’s ‘Four Heavenly Kings’, and his emblematic work Seeds of Mercury was shortlisted for the 2024 Hugo Award for Best Novella.

Hello Mr. Wang! Before we start, I would like to congratulate you on Seeds of Mercury’s shortlisting for 2024’s “Best Novella” Hugo Award. This is news that has excited countless Chinese science fiction fans. Ever since the publication of Chinese Science Fiction: An Oral History, readers have commented that your contributions have particularly appealed to them and would like to know more about your life and work. Hopefully, this long-awaited interview will provide some of the insights the sci-fi community has longed for.

Q1|Mr. Wang, despite having produced many great works, this is the first time you’ve been shortlisted for the Hugo. How did you feel when you learned that you’d been shortlisted?

Wang Jinkang: Of course I was elated. Although I’ve won many awards in China, in fact the most Galaxy Awards in history, this is the first time I’ve been shortlisted for a Hugo. It felt like 31 years ago, when I first saw The Return of Adam in print, and when I won my First Galaxy Award. I think every author experiences these moments of excitement. It’s excellent that Chinese science fiction has reached a certain level, after years of growth, it’s now more and more visible internationally, which is fantastic. Of course, what we value even more, is these works transcending their era, and surviving the tides of time to reach future generations.

■ Religion and Science are enemies who love each other.

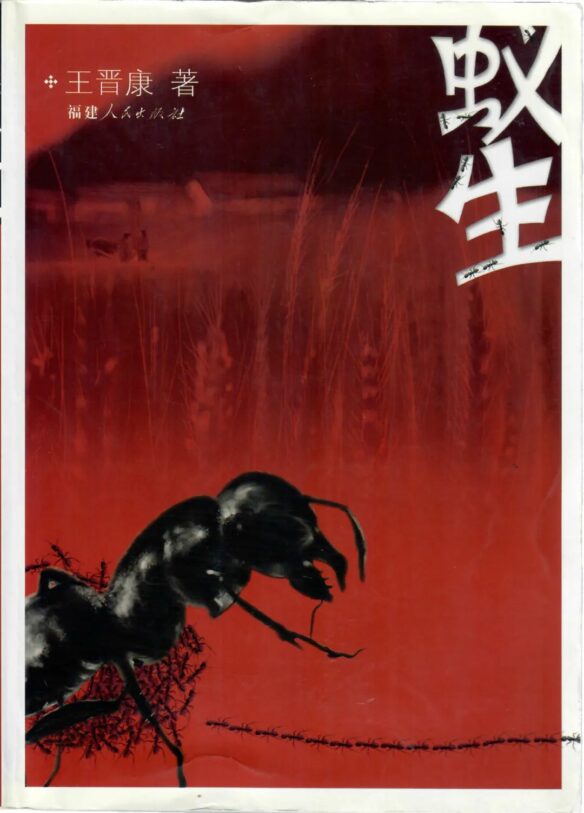

Q2|Mr. Wang, as one of the ‘Four Heavenly Kings’ of Chinese science fiction, you’re already very well known in China, with a creative career spanning over thirty years, with works such as Leopard Man, Ant Life and Survival Experiment and so on. This shortlisted work is such a quintessential piece. However, this interview is not just intended for the Chinese sci-fi fans, but for readers around the world, who may not be familiar with Seeds of Mercury. Could I ask you to introduce it for the benefit of the overseas sci-fi fans?

Wang Jinkang: Seeds of Mercury is a two-threaded story. The first one follows a female scientist named Shawu, who discovers a new formula for life, and creates a fluid metal nano life form. When she dies, she entrusts that formula to Chen Yizhe, a businessman with a pure heart, along with the message “real life cannot be bred in pens. In the Solar System, there happens to be a suitable place for it to breed freely – Mercury”. Chen Yizhe accepts this monumental legacy enthusiastically, using his personal wealth to maintain the laboratory. In order take the next step, of “seeding Mercury”, he must turn to the society around him. Mr Hong, a multi-billionaire with a disagreeable personality but a benevolent soul, decides to liquidate his empire to facilitate the spaceship’s construction. Furthermore, Hong makes another astonishing decision: to relocate to Mercury, have his body frozen in the millennia-old ice caves of the planet’s north pole, to be awakened every 10 million years, to assist the evolution of these micro-lifeforms. In just 15 years, Chen Yizhe sends Hong to Mercury to seed the nano-life into the liquid metal lakes of Mercury, after which Hong settles down in its polar caves. Meanwhile, Hong’s lawyer, and soulmate named Yin, bids her painful farewells from the distant Earth.

The second storyline is set 100 million years later, when the Suola race have evolved on Mercury, their metal bodies adapted to the hundred-degree temperatures of the planet. They are sustained by light (drawing energy directly by photosynthesis). With no sense of hearing, they rely on the flashing of light through two orifices in their abdomen to communicate in binary. The entire Suola race are devout followers of Shawu, venerate the Star Father, the great god Shawu and her earthly incarnation. They have been initiated in science, and after studying their Holy Book, scientist Tu Lala discovers that much scientific knowledge has been disguised and hidden within. From this he deduces that life on Mercury originates from The Blue Planet. He implores the high priest to send an expedition to search for the Holy Site in the depths of the ice, with the excuse of reviving the incarnation of Shawu, as the Book prophesied. The high priest consents, sending a chaplain to supervise the mission. Tu Lala actually locates the Holy Site, and discovers the incarnation of Shawu (Mr Hong), frozen in the ice, along the sacred rites of “how to revive the incarnation of Shawu”.

However, unexpected occurrences, mainly due to the ignorance and blind devotion of the believers, result in Tulala’s unfortunate violent death (as metallic organisms, the Suola can easily resurrect after a sudden death, but those who do are considered an untouchable caste). In order to protect Mr Hong’s body, Tu lala risks the humiliation, but tragically, his student Qi Qiaqia denounces him, exposing his untouchable status, and inciting the crowd to him, During which time, Mr Hong’s body is destroyed in the scorching sunlight. To avoid blame, Qi Qiaqia suddenly declares that the incarnation of Shawu was a false god, which is why the Father Star could destroy it. This narrative is accepted by the devotees, who hail him as their new high priest. In the thousands of years that follow, Suola society descends into darkness, religious cruelly suppressing science, but from among the population comes a new “Sect of Repentance”, apparently founded by an untouchable. Silently they preserve everything related to science, awaiting the next rebirth of Shawu in future millennia.

Q3|Seeds of Mercury was first published in 2002, and its appeal still endures, even after all this time. What inspired you to write this story?

Wang Jinkang: The initial inspiration probably came from a sad epiphany I had as a teenager. The human body is too fragile. Our proteins start to coagulate above 80°C, our brain suffers irreversible damage if we don’t breathe for five minutes, our body can’t withstand radiation, and we can die from disease, hunger, dehydration, drowning and freezing… It’s admirable that such a fragile life form has been propagated on for billions of years, but it also makes me apprehensive that humanity would not survive a disaster. Human civilisation is a great achievement, which is why we are proud of it; but it also makes me anxious, worrying that humanity may not survive the next cataclysm. I couldn’t help but imagine, what if a creator, or god of evolution, created a metallic life, invulnerable to fire and flood? Many years later, I combined these youthful imaginings with my subsequent concept of “Templates for Life” and turned it into this novella.

Q4|Seeds of Mercury is a piece about the sublime act of Creation, and a reflection on the transitory nature of life. Did you write it with the intention of exploring the contradiction between Science and Religion? Or did that grow naturally out of the creative process? Also, do the sentient beings you write about reflect your own views and positions?

Wang Jinkang: I didn’t intend to construct that dichotomy between Science and Religion, but it’s exactly what happened on Earth, so when I created a history for Mercury’s civilisation, those episodes just appeared naturally. Religion and Science are enemies who love each other. European Papacy cruelly persecuted Galileo, Bruno, and other ‘heretics’, and strictly forbade the theory of evolution, but medieval Europe became the birthplace of modern science. When we look back at the history of Civilisation over millennia, you can’t help but sigh that history is full of paradoxes, and that The Creator is always full of mischief, making fun of the theories of Cause and Effect. As to whether this new life carries some of my own views or positions? Of course. Tu Lala is the heir to the human spirit, with his scientific rationality, adventurous spirit, sense of responsibility, fortitude, and self-sacrifice. In the story, when Tu Lala meets the holy body of Shawu Incarnate, and he figures out that the great god was a scientist. Thus, demonstrating that the intellectual spirits of all scientists are inter-relatable, even if they are alien. That is what I believe in my heart.

■ Today’s AI isn’t quite up to the standard of “Return of Adam”

Q5|Mr. Wang, the world has moved on 22 years since the first publication of Seeds of Mercury. What changes do you think have occurred in science fiction writing in the present day, compared to the early years both in terms of the environment, and the core themes?

Wang Jinkang: These 22 years have brought great changes, and it could be said that civilisation has reached a critical point, that we’re on the cusp of drastic changes. However, for the science fiction writer, who is used to seeing the world from a god-like point of view (through the eyes of science) we think in millennia, so 22 years is too short a period to affect the themes of my work. For example, my debut story Return of Adam showed a society where AI had overcome natural humanity, though it had taken on a parasitic approach, augmenting the processing power (IQ) of the human mind to far outstrip the basic brain, and in fact, became the core of human consciousness. The rapid development of AI today, especially the LLM systems, is amazing, even frightening, but in general, today’s AI isn’t quite up to the standards of Return of Adam. Still, I’m saddened that some things I wrote about, which I assumed would be far in the future have come to pass in my lifetime. For example, in 1997, when many Chinese people asserted that AI could never triumph in the field of Weiqi (Go), I was convinced it eventually would, and wrote a scene of an ‘AI beating a human chess master’ in one of my stories, before it actually happened. I just never expected to see it in my lifetime.

Q6|Before Liu Cixin appeared, you “held up half the sky” in Chinese Sci-fi. When you first appeared in China’s science fiction circles, you were relatively older, and more experienced. Do you think that maturity allowed your work to appear more rounded?

Wang Jinkang: My life and experiences have been quite unique. I’ve lived through a very special time in China’s history, worked as a rusticated youth, a miner and model maker. I went to university at 30, became a mechanical engineer, wrote literary novels, and only broke into the science fiction world by chance at 45, publishing my first sci-fi story. If anything, my near-fanatical reading of literature at university paved the way for my future writing. At that time, the reforms were already happening in China, and it was opening up to the world. A huge amount of foreign literature was pouring into the country, dazzling readers like me. There may be another special factor, which is, because I was studying engineering, I was standing atop this wall of science and watching this river of literature racing by, I had a sense of detachment. Add to that I only started writing SF decades after experiencing the rise, fall and distilling of the wave of literature. I suppose that’s why my writing style has a poised, bleak, and sombre character.

Q7|What sort of stories do you think are expected from the current literary ecosystem? Which sci-fi genres do you expect to take off in the future?

Wang Jinkang: I have always felt that science fiction is unlike any other form of literature. The richness of mainstream literature does not necessarily coincide with the strength of a country. As the aphorisms go, “classics are born from chaos”, and “poets are fortunate when the country is not”. However, the success of science fiction is reliant on enough readers and authors being educated to a certain threshold, and so depends on the country’s economic, scientific, and technological development, which can be proven by the movement of science fiction’s centre from Britain and France to the United States over the last century. Over the past 40 years, China’s overall economic development has been good, and as one of the oldest sci-fi writers in the country, I’ve experienced this first-hand. I feel that as China continues to modernise and converge with the rest of the world, the creative environment of Chinese sci-fi will continue to improve. As for which themes, I feel will start to emerge? It’s expected that artificial intelligence and space themes, with more emphasis on exploring the human condition, are going to be the stories of importance, but other themes will also develop immensely.

■ Science fiction writers are used to seeing the world from a god-like viewpoint.

Q8| Mr. Wang, science fiction has taken root in China now for around a century, and you have played a pivotal role in the history of science fiction in the country. Irrespective of whether or not you win this Hugo Award, you have influenced a generation of sci-fi fans and creators. How do you view your own Creative Achievements?

Wang Jinkang: I’m flattered, but I only really played a leading and inductive role in the early stages of the so-called “New Generation” of Chinese sci-fi back in the 1990s. I’m content with the two aspects of my writing career, firstly, in forming the genre of Philosophical Science Fiction, which is based on the latest technological advances, and digs deep into the influence it has on alienation, civilisation, and so forth, to discover this genre’s philosophical uniqueness. This genre did not originate in my work, foreign writers including Mr. Arthur C. Clarke have long created excellent works of philosophical sci-fi, but these elements in my work are more concentrated. Furthermore, with regards science fiction as “the most cosmopolitan form of literature”, I consider my work, whilst still cosmopolitan, to be imbued heavily with Chinese styles and themes, which adds a certain flavour to the genre.

Q9|Do you feel that science fiction writing is shifting from short-form to long form, and what difficulties do you feel are associated with that?

Wang Jinkang: In my experience there are three main issues faced when moving into the long-form. Firstly, there must be enough knowledge, from the accumulation of experience and information. Secondly, there must be a more mature view of Nature and human society, in their entirety. These are not necessarily the dominant trait of the novel but will play important roles in the story’s development. Thirdly, the ability to comprehend the entirety of the larger story. This ability to grasp the complete story is equally important to mainstream literary writers, but in science fiction, concepts always play a driving role in the whole work and should be logically consistent in themselves.

Q10|In your eyes, what is the role of Morality and Ethics in Science Fiction?

Wang Jinkang: Science fiction authors often look at the world from a godlike point of view, and in the eyes of a creator, survival comes first, and morality and ethics are just auxiliary codes established by humans once they reached a certain level of civilisation. They are also conducive to the overall survival of the human race. As Humanity develops, and “co-operation” becomes more central to society, the role of morality and ethics becomes more and more important, but they certainly won’t stay the same, and the rules will certainly have additions and deletions. For example, once technology becomes suitably advance, the ethics of “strict prohibition regarding editing the genes of a human being” are very likely to change.

Q11|Throughout your career, which of your stories are you most satisfied with?

Wang Jinkang: Of my short and medium length works, I like Seeds of Mercury’, Bee Keepers and The Song of Life, and of my longer works, I’m most satisfied with Ant’s Life and the Alive Trilogy (Escape From The Mother Universe, Parents of Heaven And Earth, and Cosmic Crystal Eggs).

■ Thank you, reader, for giving meaning to my life.

Q12|Mr. Wang, some sci-fi fans have pointed out you are ‘the oldest non-American writer shortlisted for the Hugo Award’, which is an impressive feat. What are your hopes for the Hugo Awards?

Wang Jinkang: There’s a bit of a special circumstance here, where a story I wrote 22 years ago, was only translated into English last year, and shortlisted according to the translation’s publication date, even though, I’m very happy to hold this “World Record”. I hope it will go further than just being a finalist, but even if it doesn’t, I still consider it a great honour to be shortlisted.

Q13|What would you like to say to the readers regarding the inclusion of Seeds of Mercury in the Hugo Awards shortlist, which was voted for by individual sci-fi fans one after another?

Wang Jinkang: I’ve always had a reverence for my readers. The two most common inscriptions I write to fans at signings are “The reader is the god of authors”, and “Thank you reader, for giving meaning to my life”. Out of the millions of publications each year, in a sea of stories, to have any number of people read your work, enjoy it, and keep it in their memory after that relentless tide of time, is a rare blessing. One might even call it a great gift from the readers to the author.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.