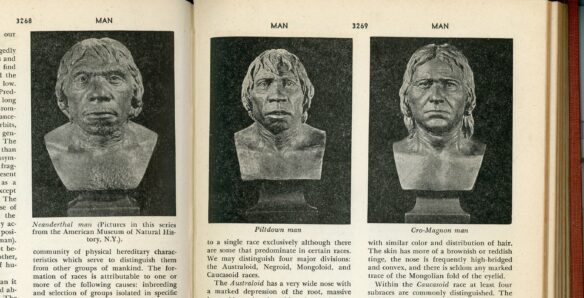

By Lee Weinstein: When I was a child, my father gave me a set of the illustrated New World Family Encyclopedia, published in 1954. One illustration that burned itself into my brain was composed of photographs of three sculptured busts of “cavemen” peering out from under the entry for “Man” in volume 12. They were labeled “Neanderthal,” “Piltdown,” and “Cro-Magnon”. The Cro-Magnon Man, aside from the pre-hippie-era shoulder length hair, looked like he could have been someone who lived down the street. But the other two, the Neanderthal and Piltdown men, had brutish faces and sinister straight-on stares that drilled into me.

It was in the ninth grade that I discovered Piltdown Man had been a hoax. My teacher told us that a little old man had confessed on his deathbed to creating the hoax. There had never been a Piltdown race. I went home and dug out my old encyclopedia volume. A hoax? He had even been assigned a scientific name, Eoanthropus dawsonii, which placed him in a separate genus from genus Homo. But there he was, staring back at me from the page. The face of someone who never was. The idea intrigued me.

Years later, I discovered that there was no little old man or any deathbed confession. There have been a number of candidates for the perpetrator of the hoax, including Charles Dawson, Pierre Tielhard de Chardin, Arthur Keith, Martin A.C. Hinton, and even Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, among others. But it is still a matter of debate. It was, nonetheless, a deliberate fraud. In 1953, very shortly before my encyclopedia had been published, Joseph Weiner, an Oxford anthropologist, had shocked the scientific world with the revelation that the Piltdown bones were artificially aged fragments of a modern human skull and an orangutan jaw. But the revelation was just a little too late to affect the encyclopedia entry. In popular culture, Piltdown Man already had a presence, from references in Edgar Rice Burroughs’s novels of the ‘teens and the Peter Piltdown comic strip of the 1930’s to the MacIntosh prototype “PDM” computer of more recent years.

He had entered my imagination as well. There was something about his non-existence that fascinated me. I decided that I wanted to meet him face to face. So I scanned the internet and plumbed the depths of the library stacks.

First, I took a closer look at the encyclopedia entry. Under the photographs was an attribution to the American Museum of Natural History in New York. That was a clue. I emailed the museum’s library and found out that the busts had been part of a major exhibit that was no longer there. The librarian had no idea of what became of them.

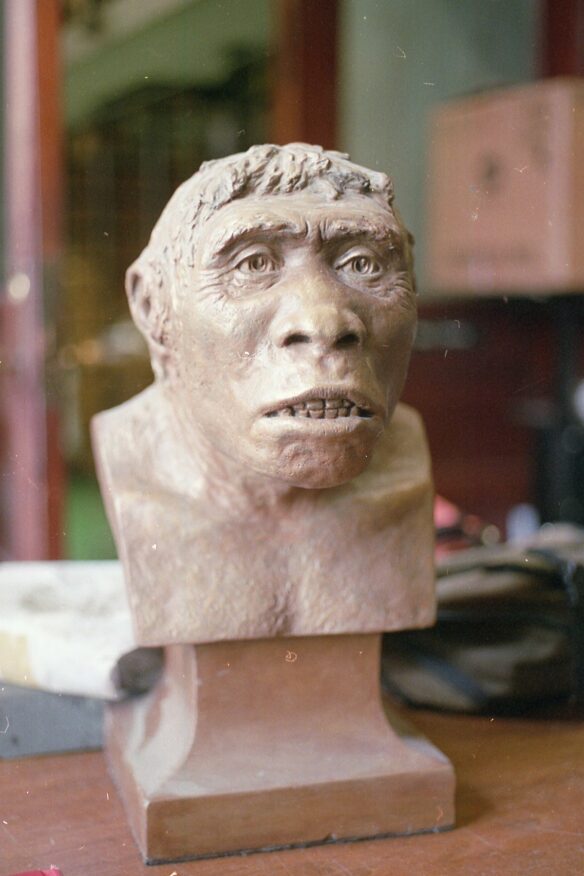

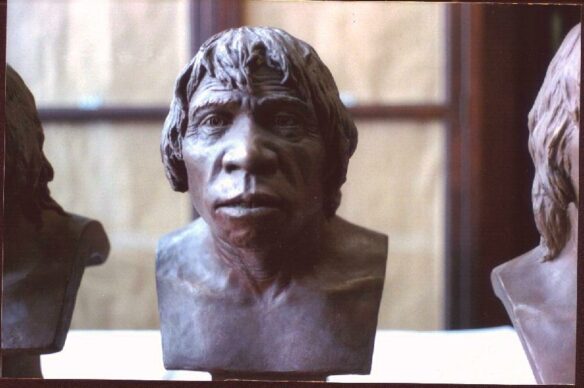

In the stacks of the Philadelphia library where I worked, I found a book called Men of the Old Stone Age (1915), by Dr. Henry Fairfield Osborn, which had more photographs of the busts in question, and others as well. The sculptor was identified as a Professor J.H. McGregor of Columbia University.

Further research revealed that in 1922, Dr. Osborn, then president of the museum, opened the exhibit, which was called “The Hall of the Age of Man”. The busts that had fascinated me had been specially made for the exhibit by Professor McGregor, who was a former student of Osborn’s and who became a Research Associate in the museum’s Department of Comparative Anatomy.

In scanning the internet, I also found another fascinating recent photograph that opened up further possibilities. It was of the familiar Neanderthal bust and posed with it was a Dr. Gary J. Sawyer, as well as a science fiction author I happened to know, Robert J. Sawyer, who had recently addressed the Philadelphia Science Fiction Society.

I sent Robert J. Sawyer an email and asked him about the photograph and how he had come across the sculptures. He replied quickly and told me that in researching his novel Hominids he had contacted Dr. Gary Sawyer (no relation to him) and Dr. Sawyer had invited him to come to the museum and get a behind-the-scenes tour. He suggested that I contact Dr. Sawyer and I could get a look behind the scenes in the museum as well.

I did so and Dr. Sawyer, a physical anthropologist, graciously invited me to let him know the next time my wife and I were in New York and he would show us around his department.

Sometime in 2001, Diane and I made the pilgrimage by rail from Philadelphia to New York. We were greeted by Dr. Sawyer, a slender, cheerful man in a white lab coat, who ushered us past the public exhibits and into his laboratory in the hidden recesses of the building.

He began by telling us that people who do such reconstructions should have artistic ability, a good knowledge of human anatomy and a background in anthropology. By way of modern examples, he showed us a replica of the “Lucy” reconstruction as well as some current projects being done in the museum.

He said he thought of himself as McGregor’s present day spiritual successor at the museum and bylined his papers G.J. Sawyer, in homage to J.H. McGregor. An anthropologist with a flair for the dramatic who clearly loves his work, he explained to us how he still employs McGregor’s techniques. An entire skull is extrapolated in clay from assorted fragments of bone. Next, layers of muscle, followed by the other soft tissues, are lovingly modeled over the skull, all to a carefully determined thickness. Ears, nose, and eyeballs are added. What had been a few pieces of a skull now has a human face.

In the office were the original busts of a Neanderthal, a Java man, a Cro-Magnon, and of course the Piltdown man that I had come to see. I saw now that the sinister and unnerving effect of the straight-on stares had been created by the pupils of the eyes being carven depressions.

We moved the life-sized plaster busts from his office and set them out on a long table, creating a veritable rogue’s gallery. The Neanderthal bust, we were told, was modeled on one of the earliest finds of skeletal remains in Chappelle-aux-Saints. He assured us that the Neanderthal bust is as accurate a rendition as any that have ever been done.

And then there was the Piltdown bust. Professor McGregor had no way of knowing that those bones he was given to work from had been deliberately doctored. Confronting Piltdown, and looking into his carved eyes with the hollowed-out pupils, I could almost hear him grunt.

I couldn’t resist taking a few photos, before thanking Dr. Sawyer and taking our leave. The one of Piltdown man, I framed and is still on display in my living room.

To most, he represents a fraud; an embarrassment. But to me, he represents imagination made concrete. He represents a reality where dragons still fly and unicorns graze.

When I looked, at last, at that face in bronze-painted plaster I knew that Dr. McGregor had done his best with the dubious bones he had been given. No, Piltdown Man never existed. But if he had, I know I can rest assured that this is what he would have looked like.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Thank you for this essay; I’ve always found the side-passages of not-quite-science fascinating. N-rays, phlogiston….

That’s fascinating. I wonder what’s become of the actual bones.

I have my own Piltdown story: prior to my first trip to England, I was scouring the map of Sussex because I was planning on visiting the Hundred Acre Wood. On the map I noticed a village called Piltdown. Was this the one that Piltdown Man came from? I checked and it was, so – always tickled by the story of the hoax – I went there too. The map directed me not to the village but a nearby golf club, where I stopped and asked, but nobody there knew where the discovery site was. Pity, because I understand there’s a monument.

Pingback: AMAZING NEWS FROM FANDOM: November 26, 2023 - Amazing Stories

Of the suspects, Dawson is the only one who had all three of motive, means, and opportunity. He also was connected to both sites, Piltdown 1, and Piltdown 2 where a second fake Piltdown skull was “found.” These were not his only finds at Piltdown, and not his only forgeries. Many of his finds over the preceding couple of decades were also exposed as forgeries. One of his other “finds” at another site, a tooth, came from the jaw used in Piltdown Man. The same techniques of aging and filing used on Piltdown Man were used on Dawson’s earlier forgeries. The flow of finds contributed greatly to his and his institution’s reputation and prosperity. Piltdown Man was the culmination of a long pattern of behavior, and the step too far that eventually prompted a reexamination of all his previous “finds,” exposing those forgeries.

Doyle’s supposed motive is that he wanted to make fools of the scientific community that was ridiculing him for his spiritualist beliefs and susceptibility to related hoaxes. But if he had created the fakes for that reason, he’d have exposed them as fakes and the “great men of science” as dupes during his lifetime. He didn’t.

The “evidence” against Teihard de Chardin is that he traveled to the right part if Africa at the right time to potentially have supplied parts of the forged Piltdown Man skull. That’s thin, at best.

I was going to say that Piltdown (or Pilt Down) is close to–say 6 miles [10 km] or so south of–Ashdown Wood, the “Hundred-Acre Wood” of the Winnie-the-Pooh mythos. That part of East Sussex is some 30 miles (48 km) south of London.

Scary, Lee? I dunno, I think I’ve seen men with that “Neanderthal” face on the street.

And one thing that has been irritating me for a while is that none of these picture makes and sculptors have ever considered whether the people – and they are people – back then might have had, you know, combs.

A great story of not just imagination but intelllectual search as well; thank you!

I always enjoy your essays. I hope someone will collect them into a book.