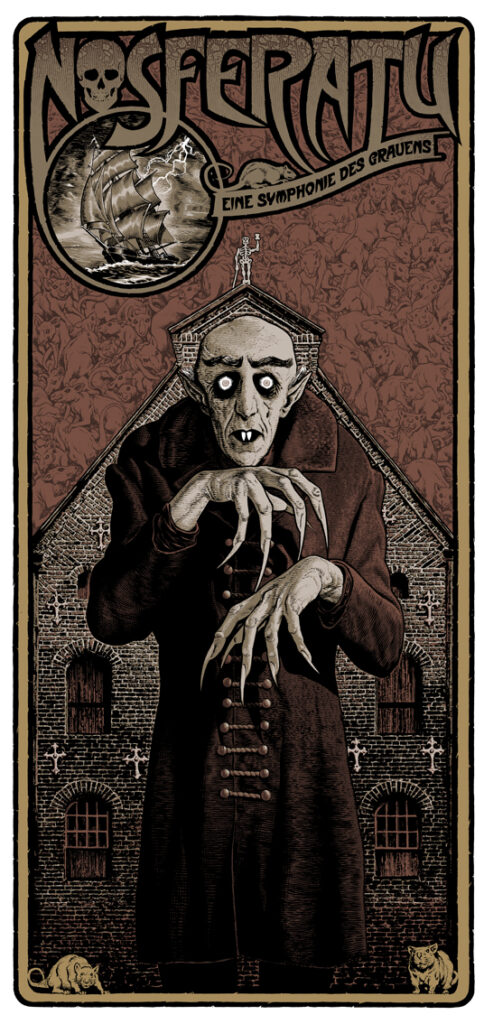

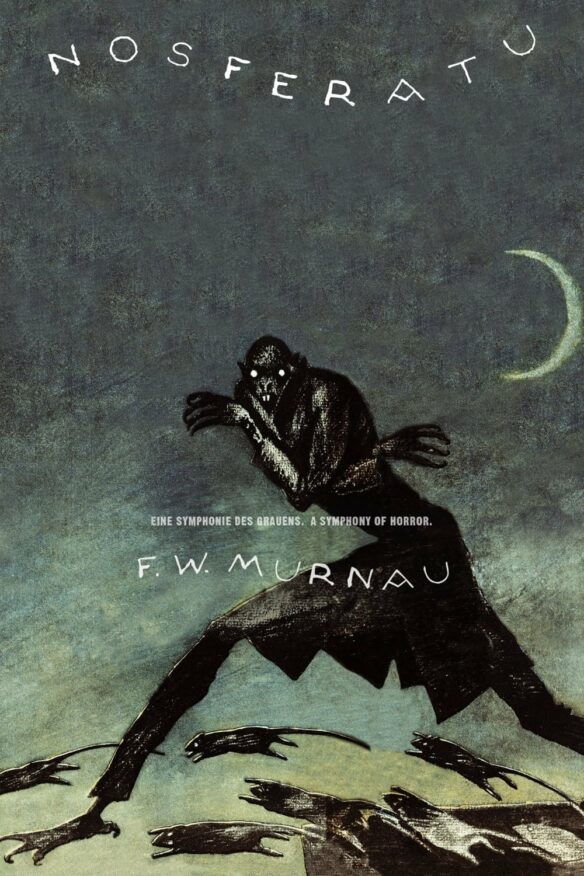

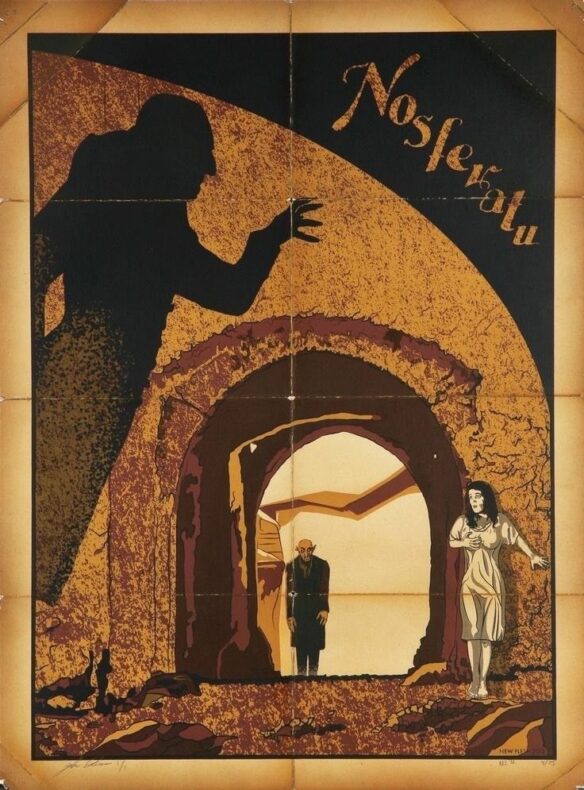

By Steve Vertlieb: Every generation has its incarnation of the grand and glorious vampire mythos – the Twilight and Underworld film series, The Vampire Diaries, HBO’s ever popular True Blood, the Gen X’er’s fondly remembered The Lost Boys, my own generation’s Dark Shadows (not be confused with the rather loopy Tim Burton theatrical redo of a couple of years back!), and even the legendary X-Files, The Night Stalker and Tales From The Darkside have more than once dipped their creative talons into that blood-soaked thematic well. But, for all intents and purposes, it all began with the most grand filmic guignol of all — F.W. Murnau’s 1922’s silent movie masterpiece Nosferatu. Then, ninety-four years after its historic cinematic inception, a small theatre company in Los Angeles, California commenced upon a most ambitious and provocative undertaking.

The Crown City Theater in North Hollywood, under the direction and inspiration of writer/director William A. Reilly, unleashed an astonishingly bizarre live stage presentation of Murnau’s silent vampire classic in 2016. Entitled Nosferatu: A Symphony In Terror, it was at once both a unique and surreal homage to the one-hundred-year-old German film magically unveiled before our very eyes.

Utilizing few props, other than a bench or an occasional chair, blackened curtains, period historical film projected onto a tiny screen, and off stage narration, Nosferatu wove an uneasy tapestry of mounting dread and near balletic poetry. A claustrophobic net, a calculating spider’s web, of necessity — drawing a comparatively tiny yet anxious audience ever more closely into its intimate spell and tendrils. It conceived a suffocating sense of palpable fear and apprehension — extending uncomfortably beyond the proverbial “footlights’ of the frighteningly intimate stage. We in the audience were lured, inescapably, into a dark nightmare from which we could not awaken. We could only scream.

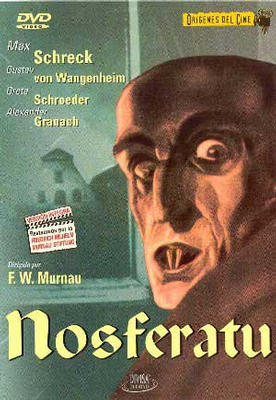

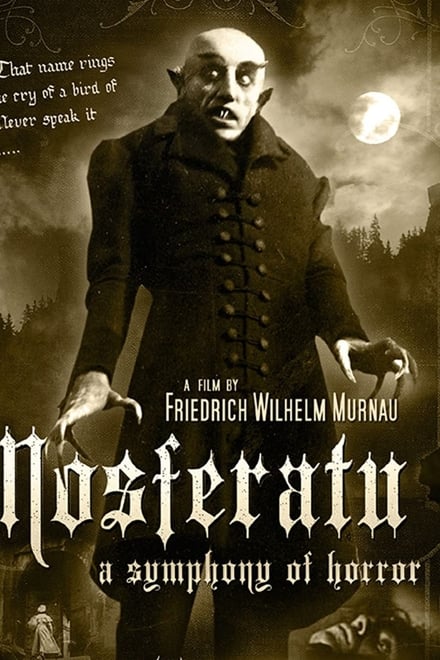

Nosferatu, F.W. Murnau’s 1922 silent film masterpiece for Germany’s UFA Studios, was the first motion picture version of Bram Stoker’s classic 1897 novel of vampire eroticism, Dracula. It was, in the strictest definition of legality and copyright laws, an illicit representation of Stoker’s acclaimed book in that the producers failed to secure permission to film the story. Nevertheless, this illegal bastardization of the globally popular British novel by an Irish author has never been eclipsed for its ferocity of brooding visual terror and Wagnerian Grand Guignol “opera.”

The film is, at its heart, a ballet of horrific imagery dancing across an outrageous palette of lyrical “grandiosity”. Murnau’s nightmarish vision of stalking corpses which preyed upon the innocent inflamed the already lurid imagination of the German populace in the Weimar Republic during the years leading up to the Second World War. Stoker’s novel had merely hinted at the erotic undertones of sexual repression in Victorian England by suggesting that Count Dracula, who had abandoned mortal existence for a world owing no allegiance to morality, might arouse sensual inhibition in his victims beyond the veil of death. Once free of the bondage of intellectual mores, might not the dead rise once more, free of conscience or societal obligation, to devour both the desires and life’s blood from the living? In many ways, Stoker’s work of horror fiction had become an allegorical fantasy for freedom from repression in much the same fashion as Robert Louis Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde.

Hyde (published 11 years prior in 1886) dealt with a potion which might release the inner soul, or baser instincts of, “polite society”, while Dracula envisioned a restricted environment in which the darker desires of an “enlightened” community might willingly succumb to the forbidden allure of sexual debasement and surrender. German cinema in the 1920s had become a veritable expressionistic laboratory for groundbreaking filmmakers and artists who shed their accoutrements of civility. Strangers in a stranger land they were; a land where experimentation would reach new heights of breathtaking design, rebellion, and artistic realization.

The filmic pinnacle of the era was Fritz Lang’s Metropolis in 1927. A monumental cinematic conception of science and technology, it teetered on the brink of mad genius in its vision of a futuristic society of uniformity and totalitarian repression ultimately consumed by the catastrophic conflict between “good” and “evil”. Actress Brigitte Helm in the dual roles of “Maria” — the virginal product of intellectual and emotional docility, and as the artificial Robotrix, brought to fiery life by mad inventor Rotwang, conveyed both innocence and erotic passion in her psychologically charged performances of conflicted identity. While Maria was the idealized vision of feminine purity and intellectual constraint, her artificially conceptualized doppelganger was a manipulative whore luring simple, hard working men to depravity and doom.

Conversely, Stevenson’s Dr. Jekyll was a thoughtful practitioner of science, a dedicated physician searching for humane passages for the downtrodden to rid themselves of the polarizing illnesses of both physical and emotional oppression. In both instances audiences (then and now) were / are left to ponder the irony of whether or not the releasing the baser, conceptually more “vile” instincts and desires of humanity might indeed free individuals to live and enjoy less complicated, tension laden lives. Or might it not? Might it have the opposite effect?

Count Orlok, the title character of Murnau’s Nosferatu, had of course long since succumbed to his own baser desires and predatory instincts. Shedding any semblance of humanity, he was a conniving creature of the night searching only to satiate his blood lust in order to attain physical immortality. A denizen of the dust, he the vampire would drain the life from his victims by sucking their blood in order to conjoin with his own. Yet, as reprehensible and disgusting as his practice was, women in particular were irretrievably drawn to his unfathomable power and dominance. Through an infinite number of published stories and motion pictures from the inception of Stoker’s novel to the present, vampire lore would grow in its often Freudian interpretations and implications, perpetuating the romantic prose relating to sexual domination of women by a power beyond their will or desire to resist.

England’s Hammer Films brought the legend to its logical “climactic” conclusion in their 1958 screen production of Dracula when Mina, portrayed by actress Melissa Stribling, smiles in nervous sexual anticipation, stimulation and ultimate surrender, as Dracula, enacted by the remarkable Christopher Lee, sinks his fangs greedily into her eagerly inviting flesh. The symbolism is unmistakable.

But arguably it is the savagely frightening features of Orlok in Murnau’s 1922 film which, even now, remain the most shocking of all incarnations, resembling a walking rodent or upright Doberman Pinscher bleached white. Klaus Kinski in director Werner Herzog’s well intentioned 1979 remake attempted to emulate Schreck’s makeup design in somewhat more muted tones, but the later version recreated little of the compelling, hellish horror of the UFA original. Schreck’s was an otherworldly creature, neither human nor animal. His feline mannerisms, gestures, and movements suggested a bizarre bestiality, while his startling appearance commanded a demented invitation and descent into madness, and to Hell.

The Orlok embodiment of the vampire would forever enter history (as well as contemporary global pop culture) thanks largely to his realization in the personage of actor Max Schreck. Known “pre Nosferatu” mainly for his work on the German stage with the Max Reinhardt theatrical company, Schreck would make the leap to the screen at a time when most of the Reinhardt company was doing the same. A time when German cinema of the period reflected a surrealistic landscape of malformed and ravenous malcontents who emerged from the shadows to devour unsuspecting humanity in a nightmarish blitz of rapturous depravity.

American cinema at the time by comparison had largely become saccharine and blandly polite in its artistic ambition, fearful of the hunger and power emanating from across the sea. Devoid of conviction or passion, and fearful of its own burgeoning sexuality, domestic film production rebelliously fought against its own darker nature by proclaiming a wholly insincere innocence that was both vapid and anemic. While some courageous American filmmakers experimented with more provocative thematic materials, the coming of sound brought with it an ocean of innocuous releases bound and determined to offend no one. Consequently, when Universal Pictures released the first official, legally sanctioned film version of Bram Stoker’s Dracula in 1931, it was a bland, colorless visualization devoid of power or soul.

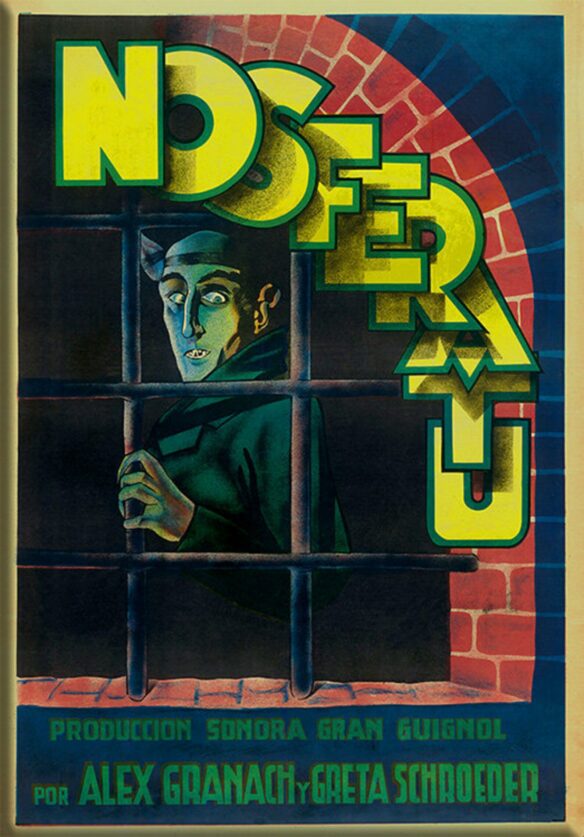

Bela Lugosi was undeniably magnetic in the title role, particularly in the early Transylvanian passages of Todd Browning’s film. But by the time the undead Count insinuated his presence in modern London, any resemblance to Stoker’s original literary conception had been corrupted and sanitized beyond recognition. A Spanish language production of Dracula was simultaneously produced by Universal for ethnic release overseas. Directed by George Melford, and starring Carlos Villarais and Lupita Tovar, it utilized the identical sets constructed for the more prestigious Browning production, and filmed on the lot in the evening hours after the American crew had departed. Astonishingly, although its lead performance contained little of the magic inspired by Lugosi in his signature role, this presumably low rent imitation of the now classic vampire tale was far more adventurous, even lurid, in its depiction of the very same story, and (lost for many years until recently) remains the superior film.

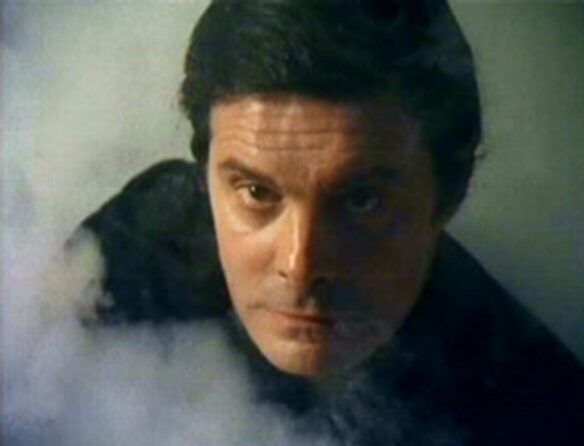

With all due respects to both versions (as well as to Universal’s marketing of the Lugosi image over the last near century), it is Murnau and Schreck’s “pale rodent”-like personage of Orlock which has sunk its teeth into the pop culture mainstream like no other. In addition to 1979’s Klaus Kinski / Werner Herzog version of Nosferatu (it incidentally released the same year as Universal’s big budget Dracula starring Frank Langella and Sir Laurence Olivier), Thanksgiving week of that same year gave TV audiences a very good reason to cow, shudder and leave the lights on with CBS’s terrifying mini-series rendition of Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot.

Co-produced by the legendary Stirling Silliphant, and directed by Texas Chainsaw Massacre / future Poltergeist director Tobe Hooper, it is still regarded to this day by many as one of the scariest programs ever broadcast on a commercial network – thanks not only due to Hooper’s atmospheric direction, but also to a stunning trio of stars including James Mason, David Soul, and especially Reggie Nalder as the hell-spawn vampire “Mr. Barlow”. With both King and Hooper being great fans of Murnau’s film, “Mr. Barlow” is a deliberate dead-ringer (pun entirely intended) modern day version of Schreck’s Orlock.

Thirty years after the creation of Bram Stoker’s literary masterpiece Dracula, Hamilton Deane, the son of Stoker’s boyhood friend, decided to translate the novel for the London stage. An actor and playwright, Deane’s theatrical interpretation premiered at the Little Theatre in London on Valentine’s Day, February 14th, 1927, running for 391 performances, with an additional three years in the provinces. Deane often appeared in these productions as Van Helsing. So potent was the resurgence of interest in Dracula that American producer/publisher Horace Liveright imported the successful play to the New York stage where it opened at the Fulton Theatre on October 5th of the same year.

Presented in a “slightly different version” than the English play, Deane seemed to acquire a mysterious, uninvited collaborator in the person of American journalist and foreign correspondent John L. Balderston who later co-authored the screenplays for Bride of Frankenstein and Gone with The Wind. Starring on Broadway in the title role of the play was a little known Hungarian actor named Bela Lugosi who would recreate his performance four years later for the first sound motion picture based on Bram Stoker’s novel.

The New York engagement of the play ran for 261 performances and then enjoyed huge success on the road. And the rest, as they say, is history.

History, however, often repeats itself and, fifty years later, on October 20th, 1977, a brand-new production of Dracula opened at the Martin Beck Theatre on Broadway. Directed by Dennis Rosa, with celebrated scenery and costumes designed by Edward Gorey, the enormously popular revival starred the gifted romantic actor Frank Langella as the Count.

Langella would enjoy somewhat modified success several years later in a similarly inspired revival of William Gillette’s Sherlock Holmes for The Williamstown Theatre, but it was this inspired production that all too briefly elevated the sensitive actor to star status. Dracula, The Vampire Play enjoyed newfound success on the New York stage and generated numerous road companies across the country. Count Dracula “lived” again.

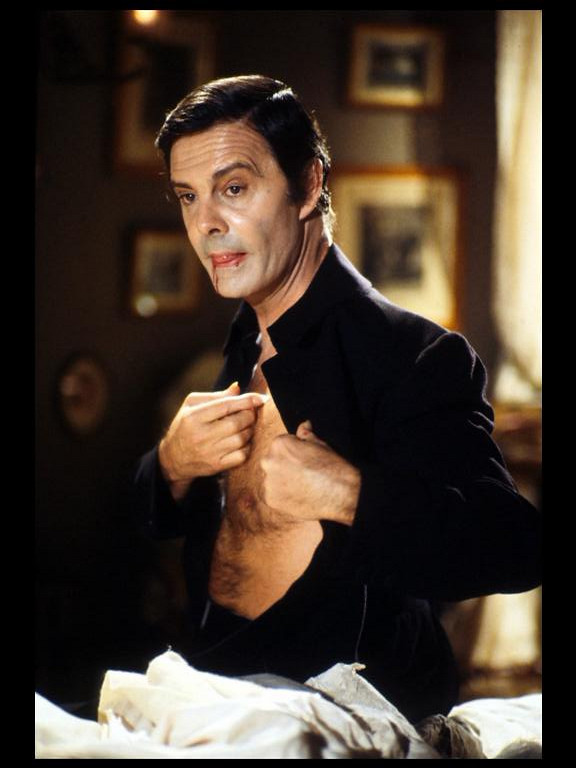

Neither the enormity, nor the importance, of this new stage production had escaped the notice of the British Broadcasting Corporation for, on Halloween night, 1977, the BBC in conjunction with America’s Public Television, broadcast their own version of Bram Stoker’s novel. Count Dracula, as scripted by Gerald Savory and directed by Philip Saville, would quickly become and remain the definitive interpretation of the famous novel.

The casting of the title character, as it had so often occurred before, (Lugosi, Langella) would lean toward a romantic leading man or matinee idol. French actor Louis Jourdan, who had scored so well for MGM in Madame Bovary with Jennifer Jones in 1949, for Universal with Letter from An Unknown Woman with Joan Fontaine in 1948 and, again, for MGM with Gigi, in 1958, was cast in the leading role. His Count was suave, debonair and lethal. Appearing with Jourdan were Bosco Hogan as Jonathan Harker, Judy Bowker as Mina (later to star as the heroine for Ray Harryhausen and Charles Schneer in their production of Clash of The Titans), Susan Penhaligon as Lucy, Jack Shepherd as Renfield and Frank Finlay as Van Helsing. The BBC production offered standout performances by all of the cast, particularly by Jack Shepherd as Renfield and, in perhaps the most compelling interpretation of the character ever enacted, by the redoubtable Frank Finlay, second only to Peter Cushing, in his powerful portrayal of Professor Van Helsing. (Finlay later turned the tables on himself as scientist turned vampire in Tobe Hooper’s epic science fiction drama Lifeforce (1985)).

Dramatist Gerald Savory had been drawn to the Dracula novel since 1920 when, as an eleven-year-old boy, he and his brother, with the two children of their mother’s friend, had been read the story aloud in varying dramatic styles by both women whilst vacationing in Folkstone, England for the Easter holidays.

Savory’s mother, an actress and leading lady of the period, was rather prim and proper in the reading of her chapters. Her friend, an actress as well, was more animated and expressive in her performance, chilling the children’s blood with nightmarish renderings. More than fifty years after that memorable vacation, the writer fulfilled a lifelong ambition, turning his favorite novel into a highly literate television play.

Additionally, he turned the teleplay into a novel published the same year in England by Corgi Books. In the book’s preface he writes ‘Above all, I believe that both the television version and the following pages will give a very clear idea of what first, rather surprisingly, stuck in my schoolboy mind and which is the core of the original novel – the struggle between good and evil. Whatever Count Dracula represents – Satan, beast or virulent disease – Professor Van Helsing lays it on the line. “Evil will not disappear just because we disapprove of it. We must fight.”

The superlative production of Count Dracula which aired on Halloween night, 1977 has been acclaimed during the past forty years for its literacy and remarkable faithfulness to the original Stoker novel.

Its settings and set pieces remain startling and shockingly effective.

At Castle Dracula, Harker is unnerved while shaving as Dracula enters the room and casts no reflection in the small mirror. The Count mocks him by placing his fingers upon the glass surface, reflecting not even a shadow. Hurling the mirror out the castle window he admonishes his guest, warning him that mirrors are “stupid things. You shouldn’t trust them.” Later Harker peers out the window of his bed chamber where he sees Dracula crawling face down across the castle wall, flopping his legs and belly like some monstrous winged rodent, whereupon the stricken ‘guest’ falls back upon the bed in horror. Now convinced that his life is in deadly peril, the solicitor himself climbs the castle wall, and descends dangerously into the deserted courtyard. There he enters another cavernous alcove, a burial chamber. The vault is lined with large black coffins. Dracula’s sleeping corpse lies serene within one of the boxes. As Harker lifts a shovel to smash the body of his host, Dracula turns to meet his gaze, untroubled by the threat.

His eyes burning red in their fury, with cheeks bloated and gorged, he smiles leeringly at his guest, while Harker runs screaming in horror from the crypt.

Count Dracula is filled with perverse, erotic imagery. Rather than feasting upon the blood of his witless guest, Dracula offers his brides a small, wriggling body hidden within a concealed bag. It is, presumably, the desperately struggling body of an abducted infant.

Back in England, Lucy wanders somnambulistically across the coastal beach, ravaged and seduced by the vampire, growling gutturally as he siphons the blood gurgling, unashamedly, from her veins. Mina arrives to return the exhausted Lucy to her bed where, earlier, a large, tentacled bat had lain, expectant, across the bed covers. Their departure is observed by the vampire, arms outstretched, bathed loathingly in enveloping wind and fog.

Attempting to make her daughter more comfortable (Mina and Lucy are sisters in this version, rather than friends), Mrs. Westenra removes the garlic necklace from Lucy’s throat, rendering her vulnerable once more to the toxic “kiss of the vampire.”

The window shatters, and a huge white dog confronts the women, snarling its contempt, as the mother suffers a fatal heart seizure. Sexually entranced, Lucy abandons her mother, giving herself instead to the now fully metamorphosed Dracula standing by her bed. The vampire wraps himself, spread-eagled, around her supine body, feeding hungrily on her blood.

Another change from the book to the telefilm was the combining of two characters, Quincy Morris and Arthur P. Holmwood, in order ‘to form a more perfect union’ named Quincy P. Holmwood. Lucy, now under Dracula’s spell completely, extends her tongue suggestively to Quincy, a blatant invitation to her shocked, staid fiance, to partake freely of her ample sensual delights. When Van Helsing advises him to stay away from her, she growls menacingly and succumbs. Later, much as Peter Cushing as Van Helsing had rendered his Lucy impotent, Finlay’s professor impales the undead young woman with a stake decisively plunged into her heart, stuffs garlic cloves into her mouth and severs her head from her body. In another particularly powerful extract from the original novel, a disturbing mist sweeps beneath Mina’s bed chamber door, finally solidifying as the vampire prince. Jonathan sleeps beside her as though drugged, unresponsive to her urgent cries for help.

As Dracula initiates Mina into the rites of the undead, he calls her “my beautiful wine press,” and promises unto eternity that “we shall cross land and sea together.”

In the ultimate expression of his animalistic craving for her, he slashes his own chest and presses her lips against the newly opened wound, inviting her to drink deeply and partake of his blood. When she awakens, Mina screams ashamedly, tearing at her bloodied nightdress and proclaiming herself “unclean.”

Harker, Van Helsing and Holmwood race to Carfax Abby in search of Dracula. In the ensuing confrontation, the light of the crucifix shines upon the vampire’s countenance as he calmly defends, to those who would make him their prey, his right to survival. His active, and continuing recruitment of disciples, is little different from their own, in sublime service to their lord, he explains. Hs ravenous feeding on Mina is no worse than their gorging on a cooked bird for supper. “We all must survive,” he says. “Where is the difference?”

At campfire, en-route to Dracula’s castle, Van Helsing and Mina are attacked by the Count’s vampire brides, repelled only by the holy circle in which they cower, protected by the power of the eucharist strewn at their feet.

As dawn breaks, Van Helsing completes the journey to the castle and impales the terrible sisters, lying helplessly in their coffins. The companions are reunited late in the day, as Dracula’s henchmen bring their sleeping leader home to the courtyard of his castle. There, a climactic fight commences in which Quincy is fatally wounded. Van Helsing rips the lid of the coffin off its hinges as the sun begins to set. His eyes open, a single word – “Sunset~” – escapes the vampire’s smiling lips as Van Helsing’s stake plunges deeply into Dracula’s chest. As he screams, the life energy of the centuries old aristocrat explodes into the night air, an impassioned wind clinging desperately to its fading seconds of existence, dissipating mournfully in the invigorating rays of moonlight, comforting the still countryside. In the final analysis Count Dracula is a masterful visualization of Bram Stoker’s inspiration, and the finest production of the story ever photographed.

Director Tim Burton (Edward Scissorhands, Beetlejuice), also a huge fan of Nosferatu, would pay pop-culture homage to the 1922 film in his own 1992 film sequel, Batman Returns, by patterning two of the film’s trio of villains after the famous Orlock visage: Danny DeVito visually cast in the Orlock mode as The Penguin, and Christopher Walken’s “ethically challenged” retail magnate being named (what else?) “Max Schreck”. Then in 2000, Nosferatu fan Nicolas Cage’s Saturn Films shingle produced the critically acclaimed Shadow Of The Vampire. A “metafiction” (self referentially blending fact, fiction and speculation) POV on the filming of Murnau’s 1922 silent classic, Shadow humorously (and at the same time terrifyingly) posits that actor Max Schreck (portrayed in the film by an Oscar nominated Willem Dafoe) was actually a real vampire hired by director Murnau (John Malkovich) to be in his film; and as such was by definition the first true method actor.

Then, in 2016, a provocative new theatrical presentation took to the “live” stage in Los Angeles, produced by the city’s venerable Crown City Theater, entitled Nosferatu: A Symphony In Terror.

Utilizing classical music and tantalizingly rhythmic ballet, while fabricating its chilling other-worldly descent, Nosferatu, under the direction of William A. Reilly, aspired to an ethereal, if deadly mood and atmosphere. Mist consumed the theater, as we joined cast members on their precarious journey to the Transylvanian mountains, and the wild, disturbingly unnatural terrain surrounding the vampire’s castle. We, together with the play’s tragic protagonist, surrendered and succumbed to the brooding horror eradicating reason and prayer; mournful strangers in a deranged, haunted landscape. It was in the very simplicity of performance and sparse set decoration that our vulnerability, as characters and participants in this journey of despair, became somehow heightened with mounting alarm and insistent, crawling apprehension.

The casting of professional, if unsung, actors and actresses in this remarkable equity production was quietly impressive. With strong yet understated performances by each of the character leads, there existed an expressive eloquence of soul, reflecting the subtle tradition and historic nobility of mime. And with the notable absence of spoken dialogue, great performances truly emanated from the purity of articulate faith.

Michael J. Marchak portrayed Thomas Hutter, an unfortunate newlywed chosen by his unscrupulous employer to undertake the perilous journey to Castle Orlok in order to allow their mysterious client to sign the papers of a secretive real estate purchase. Hutter’s disquieting transition from traditional home and hearth in England, his reason savagely torn from him as sanity trembled upon the brink of madness, was disturbingly conveyed by Marchak as anxiety insidiously consumed him.

Alina Bolshakova, a strikingly beautiful Latvian actress and accomplished ballerina, portrayed Ellen Hutter, the innocent young bride left behind with her fantasies, who slowly comes to realize the horrific demonic plague preying upon her husband and, ultimately, the once comforting world of her birth. As Ellen, Bolshakova brought an earnest, touching sadness to her characterization. She is a simple, fragile creature who must fight desperately in order to preserve the last remnants of goodness and purity in her life, finding salvation from depravity and despair. Her lithe movements and poetic features signified a tragic remembrance of simplicity as it was, a dramatic counterpoint symbolizing the eternal battle between goodness and inherent evil.

However, the most profoundly astounding, and original aspect of Reilly’s casting of his principle actors was in his choice of performer to play the dreaded Count Orlok. With aquiline features, somnambulistic majesty, and disturbingly feline affectation, the lifeless symmetry of Orlok’s imperial dominance was here enacted with unsettling command. The anxiety perpetuated by his appearance on stage is nearly unfathomable. There is something wrong, terribly wrong, with this terrible visage. And it is only some time later that the mind numbing realization of his identity became bone chillingly apparent. Orlok, like Peter Pan before him, among the greatest of theatrical traditions, was portrayed by a woman … an actress named Michelle Holmes, slight of build, and yet evocatively creepy beyond rational descriptiveness. This startling revelation devours your senses, rendering one’s other worldly perception of the production and its intoxicating atmosphere irrevocable and all consuming. It is genius at the summit of its inspired artistry.

Nominated for an Ovation Award for her portrayal of Frau Blucher in the Doma Theater Company’s production of Young Frankenstein, Ms. Holmes also portrayed Elizabeth Procter in the International City Theater City’s staging of Abagail/1720, and played “Angela” in Oleg Larin’s short film Impasse Of Light.

All aspects of this unique stage production were uniformly excellent, including the sober narration performed by actress Saige Spinney, the deliberately understated choreography by Lisaun Whittingham, and the minimalist set and light design by Zad Potter. It was William A. Reilly’s enthusiastic vision and direction however, as well as strong, poignant performances by leads Alina Bolshakova and Michael J. Marchak, which heightened the startling levels of creativity and brilliance necessary to surrender both a willing suspension of disbelief and decidedly uncomfortable intimacy to the presentation.

While most creators would find the phrase “triple threat” to be an impressive compliment, remember the name “William A. Reilly”, for he was a verifiable “quadruple threat”. Not only was he Nosferatu’s director and playwright, but (as co-founder of the Crown City Theater) he was also one of the play’s producers. As a composer he’s written numerous scores for a variety of film and television programs, and was responsible for the music to Crown City’s own stage production of Fion the Fair, as well as The Hunchback of Notre Dame, Obsession and more.

Among the most unforgettable set pieces created for the original 1922 UFA motion picture was the astonishing sequence aboard the schooner “Empusa”, its ominous churning in calamitous seas as Count Orlok rises from his coffin like a phoenix from the ashes of Valhalla to feed upon the terrified crew. His startling ascension from the crate in which he slept, arising stiffly like an inanimate wooden plank, remains an incomparable visual achievement. And that classic unforgettable moment is astonishingly recreated live on stage: a brazen display of theatrical “smoke and mirrors” which nearly brings the audience to its feet in awe struck appreciation.

Intimacy in a theatrical setting is usually most effective when used in a small, dialogue driven play, economically limited in its scope and pretension. In this claustrophobic environment, however, the terror of vampires and impending doom became somehow smothering, and undeniably personal; compelling audience members to become immersed within its singular reality. The concept of producing a nearly one-hundred-year-old German silent film classic as a live stage presentation in Los Angeles, California in 2016 was understandably a provocative choice for a small equity theater. And the fact that it had reached fruition in such a dramatically realized, artistically compelling production as Nosferatu was nothing short of astounding. Director William A. Reilly and his talented troupe of actors and technicians had created a work of power and poetic beauty, having risen above nearly a century of respectful thematic “reprise” to contribute a genuinely new and significantly fresh chord to an iconic “Symphony in Terror.”

SAILING UPON “THE LAST VOYAGE OF THE DEMETER”

Andre Ovredal’s The Last Voyage of the Demeter is a handsome, literate, utterly chilling interpretation of a chapter (“The Captain’s Log”) from Bram Stoker’s original 1897 novel Dracula, in which the inhabitants aboard a doomed sailing vessel are fed upon by a carnivorous, bat like creature whose very survival depends upon the consumption of blood from living souls. Crates of coffins filled with soil from his Transylvanian homeland lend comfort, protection, and survival to a virtually ageless denizen of the night whose corrupt sustenance remains fertile by the insidious draining of human lives.

Surreptitious passage within the bowels of the accursed ship have been arranged by unsuspecting agents of the vampiric Count whose thirst for blood is satiated by ever dwindling numbers of emotionally crippled sailors, while the tragic voyage draws ever nearer to English shores. It is there that Count Dracula will commence a new, decadent infestation of the British Isles and her inhabitants. Terrifying glimpses of a hellish winged creature stalking the darkened corridors of the wooden craft are hauntingly reminiscent of Max Schreck’s portrayal of “Nosferatu” in the expressionistic 1922 German film classic directed by F.W. Murnau, perhaps the most indelibly horrifying visualization of the Dracula legend ever presented on film. Murnau’s vision is stunningly resurrected by Ovredal in his gripping, understated thriller.

Subtle scripting by Bragi F. Schut and Zak Olkewicz lend ominous shadings to the growing fear and suspicions of the Demeter crew, and her captain, while stunning cinematography by Roman Osin and Torn Stern bring horrifying imagery to the immaculate production. Composer Bear McCreary’s ominous scoring lends subtle horror to the visualization of the classic vampire tale, while the understated performances of actors Liam Cunningham as the captain of the corrupted vessel, and Corey Hawkins as its undaunted shipmate lend tragic credibility and subtle shadings to the horrific screenplay.

Javier Botet as the infamous “Nosferatu” offers a nightmarish interpretation of the vampiric denizen of the night in a decadent re-imagining of Max Schreck’s unforgettable visage, a graven mask of unspeakable horror and monstrous depravity. The corruption of innocence, embodied by youthful Woody Norman as the captain’s grandson, Toby, at last consigns the vessel and its doomed crew to the cavernous bowels of hell as The Demeter sails its final voyage across the churning, unfathomable sea.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I’m clicking so that I remember go come by and read this again.

I need to look up the Louis Jourdan version: and definitely see Last Voyage of the Demeter.