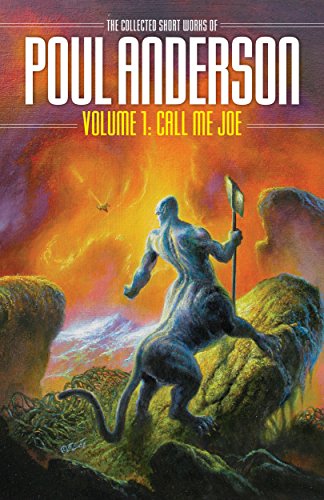

The Collected Short Works of Poul Anderson. Volume 1: Call Me Joe. Edited by Rick Katze and Lis Carey. (NESFA Press, 2009)

By Paul Weimer: Call Me Joe by Poul Anderson strongly starts off a NESFA Press series of volumes covering the work of one of the key 20th century writers of Science Fiction, Poul Anderson.

In the introduction, co-editor Rick Katze, states “This is the first in a multi-volume collection of Poul Anderson stories. The stories are not in any discernible pattern”. The pieces of fiction are an eclectic mix of early works in his oeuvre, mixed with poetry and verse that range across his entire career.

The table of contents can be found here.

The introduction is not quite correct, in that the reader can find resonances between stories, sometimes in stories that are consecutively presented. There are plenty of threads of SFnal goodness here, and a fan of Anderson and his Nordic viewpoint might call it a skein, a tangled skein of fictional ideas, themes, ideas and characters. The same introduction notes that a lot of the furniture of science fiction can be found in early forms here, as Anderson being one of those authors who have made them what they were for successive writers. In many cases, then, it is not the freshness of the ideas that one reads these stories for, but the deep writing, themes, characters and language that put Anderson in a class of his own.

The titular story, for example, “Call Me Joe”, leads off the volume. It is a story of virtual reality, or telepresence, in one of its earliest forms, about Man trying to reach and be part of a world he cannot otherwise interact with. Watchers of the movie Avatar will be immediately struck by the story and how much that movie relies on this story’s core assumptions and ideas. But the story is much more than the ideas. It’s about the poetry of Anderson’s writing. His main character, Anglesey, is physically challenged (sound familiar). But as a pseudojovian, he doesn’t have to be and he can experience a world unlike any on Earth:

Anglesey’s tone grew remote, as if he spoke to himself. “Imagine walking under a glowing violet sky, where great flashing clouds sweep the earth with shadow and rain strides beneath them. Imagine walking on the slopes of a mountain like polished metal, with a clean red flame exploding above you and thunder laughing in the ground. Imagine a cool wild stream, and low trees with dark coppery flowers, and a waterfall—methanefall, whatever you like—leaping off a cliff, and the strong live wind shakes its mane full of rainbows! Imagine a whole forest, dark and breathing, and here and there you glimpse a pale-red wavering will-o’-the-wisp, which is the life radiation of some fleet, shy animal, and…and…”

Anglesey croaked into silence. He stared down at his clenched fists then he closed his eyes tight and tears ran out between the lids, “Imagine being strong!”

Reader, I was moved.

And that is really just the surface layer of the story. The story can be seen as a contemplation of what it means to be human. Is Joe human? And if not, why not? This is a philosophical argument that occurs both in the text of the story, and presented to the reader for them, to ponder, too.

That’s only part of the genius of Anderson’s work shown here. Anderson has many strings in his harp and this volume plays many of those chords. And even here in Anderson’s earliest of stories, you can see the power and strength and evocation of his writing that draws me in as a reader. He’s not the stylist Zelazny could be, but Anderson may be very high A tier instead of S tier in that regard.

There is the strong, dark tragedy of “The Man Who Came Early” which is in genre conversation with L. Sprague De Camp’s “Lest Darkness Fall” and shows an American soldier, circa 1943, thrown back to 11th century Iceland and, pace Martin Padway, doing rather badly in the Dark Ages. It’s a cautionary tale in an Andersonian mode, and possibly a “Take that” at De Camp. It’s interesting that the story is not told from the time traveler’s point of view, which colors and shapes the narrative in a nuanced and interesting way, giving it the feel of a legend.

Poul Anderson is much better known for his future history that runs from the Polesotechnic League on through the Galactic Empire of Dominic Flandry, but this volume has three stories of his other future galactic civilization, where Wing Alak manages a much looser and less restrictive galactic polity, dealing with bellicose problems by rather clever and indirect means. In fact, the restrictions on him and his office and position mean that he absolutely can’t just shoot his way out of problems, be it trying to capture a fugitive on an alien planet, or keeping a planet from deciding to conquer a swath of a galaxy not really armed for war. It is interesting to compare him to his later creation of Flandry, and of the galactic Empire in his future history.

But the Empire in the Wing Arak stories is a going concern, loose and not very authoritarian (quite to the contrary) but it is not an empire on the way down. The classic Voltaire quote comes to mind:

“History is only the pattern of silken slippers descending the stairs to the thunder of hobnailed boots climbing upward from below.”

The Flandry novels and stories (of which there are none in this volume) are the story of Flandry trying to slow and manage the descent of stairs for the Galactic Empire. Flandry is trying to keep the descent down the stairs from being a neck-breaking fall. The Wing Arak stories are him keeping the Empire going up the steps.

And one could write a whole essay, or even a book on how Anderson views the cycles of Empires versus, say, Asimov.

And then there are his time travel tales. “Time Patrol” introduces us to the entire Time Patrol cycle and Manse Everard’s first mission. I’ve read plenty of his stories over the years, but this first outing had escaped me, so it was a real delight to see “where it all began”. Wildcat has oil drillers in the Cretaceous and a slowly unfolding mystery that leads to a sting in the tail about the fragility of their society. And then there is one of my favorite Poul Anderson stories, period, the poetic and tragic and moving “Flight to Forever”, with a one way trip to the future, with highs, lows, tragedies, loss and a sweeping look at man’s future. It still moves me.

And space. Of course we go to space. From the relativistic invasion of “Time-Lag” to the far future of “Starfog” and “The Sharing of Flesh”, Anderson was laying down his ideas on space opera and space adventure here in these early stories that still hold up today. “Time-Lag”’s slow burn of a captive who works to save her planet through cycles of invasion and attack, through the ultimate tragedy of “Starfog” as lost explorers from a far flung colony seek their home, to the “Sharing of Flesh”, which makes a strong point about assumptions in local cultures, and provides an anthropological mystery in the bargain. Those last two have been since retconned as being taking place long after the time of Dominic Flandry, but really, they stand alone in their own universes with no real connective tissue.

“Kings Who Die” is an interesting bit of cat and mouse with a lot of double dealing espionage with a prisoner aboard a spacecraft.

Finally, I had known that Anderson was strongly into verse and poetry for years, but really had never encountered it in situ. This volume corrects that gap in my reading, with a variety of verse that is at turns, moving, poetic, and sometimes extremely funny. The placing of these bits of verse between the prose stories makes for excellent palette cleansers to not only show the range of Anderson’s work, but also clear the decks for the next story.

The last thing I should make clear for readers who might be wondering if this volume truly is for them is to go back to the beginning of this piece. This volume, and its subsequent volumes, are not a single or even multivolume “best of Poul Anderson”. This is a book, first in a series, is meant to be the best of the best of Poul Anderson. This makes it different than the Zelazny volumes I reviewed in 2024 in this space, but doing it for Anderson rather than Zelazny. I do note that there isn’t a biography piece here as in the Zelazny pieces, and the lack of strict chronology means it feels less than a procession and journey through Anderson’s work (as the Zelazny volumes did) and more of a succession of sipping at the well of the waters of Anderson’s oeuvre.

Anderson did write longer and more prolifically than Zelazny and I will be curious as to what stories are included and what stories wind up not making the cut in these volumes. I’ve read a fair amount of Anderson, and it will be interesting what editorial choices are ultimately made in these books.

This is not the book or even a series to pick up if you just want the best of the best of a seminal writer of 20th century science fiction. This volume (and I strongly suspect the subsequent ones) is the volume you want if you want to start a deep dive into his works in all their myriad and many forms. There is a fair amount from the end of the Pulp Era here, and for me it was not all of the same quality. I think all of the stories are worthy but some show they are early in his career, and his craft does and will improve from this point. While for me stories like the titular “Call me Joe”, “Flight to Forever”, “The Man Who Came Early”, and the devastating “Prophecy” are among my favorite Poul Anderson stories, the very best of Poul Anderson is yet to come.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

May I beg to point out that Poul Anderson’s Psychotechnic League series and Technic Civilization/Terran Empire series are entirely separate? The first became obsolete when WWIII didn’t happen on schedule. The Wing Alak stories are also separate from the other two. I edited the first packaging of the Psychotechnic League stories for Tor and helped on the slightly different Baen version. I provided the chronology of the Technic Civilization series attached to its various volumes and editions. I did quite a few introductions/afterwords to various Anderson books (including ones on Flandry and Van Rijn) and edited a number of short story collections for Tor and Baen. I also wrote a critical chapbook Against Time’s Arrow: The High Crusade of Poul Anderson (Borgo, 1978) as well as entries on him in reference books. Credentials, much?

“Kings Who Die” is also an early example of human-computer interfaces in SF, and a still-interesting speculation as to where it might lead.

I have the whole set, although I already owned most of the stories, but there are some rarities here. Still, i have two nits to pick:

1) the stories are the magazine versions, and Poul Anderson sometimes rewrote them for book publication. An extreme exemple, so to speak, is “The Long Remembering”, first published in F&SF, 11/57. At the time, Poul Anderson was corresponding with French prehistorian and SF writer Francis Carsac (aka François Bordes), who when reading the story pointed out some minor mistakes (he also translated the story into French and mentioned these mistakes in an introduction); when the story was reprinted in the “Homeward and Beyond” (1975) collection, Anderson corrected the mistakes.

2) there are quite some typos in the NESFA book(s), unfortunately.

Do they really call “Journeys End” “Journey’s End”?

The book includes “Barbarous Allen,” which Anderson subtitled “A Filk Song,” making it the first intentional filk song ever published. The first printing omitted the subtitle, and I pointed that out; I don’t know if NESFA fixed it in subsequent editions.

Jeff Smith: My copy (1st printing) has “Journey’s End.” Was it originally “Journeys End”?

Gary McGath: yes, the story’s title is “Journeys End,” from Shakespeare’s “The Twelfth Night,” Act II, Scene III: “Journeys end in lovers meeting (*)”–which is ironic considering the story’s conclusion. Of course, Poul Anderson’s title has sometimes been altered in subsequent reprints, but the original publication in F&SF is indeed “Journeys End” (I just checked.) I remember reading somewhere (probably in a intro by Anderson in a collection) that editor Anthony Boucher was especially vigilant when the issue went to the printer…

(*) This quote is often alluded to in Shirley Jackson’s “The Haunting of Hill House”, and Shirley Jackson was an avid reader of F&SF–which published some of her stories.