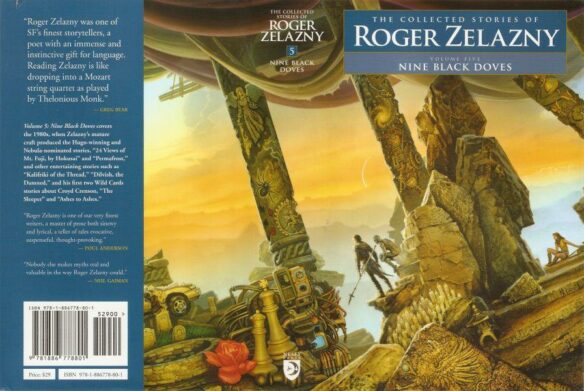

The Collected Stories of Roger Zelazny: Volume 5: Nine Black Doves, Edited by David G. Grubbs, Christopher S. Kovacs and Ann Crimmins (NESFA, 2023)

Review by Paul Weimer: Nine Black Doves is the fifth and the penultimate volume in the six book NESFA series collecting the short fiction of Roger Zelazny.

When last we left the career of Roger Zelazny, Zelazny was starting to work his way writing through the Amber novels, and that, and other considerations meant that his short fiction output had continued to steadily decrease. In Nine Black Doves, we continue those trends, as the period of his work and life covered ranges from 1982 to 1990. Let’s dig in.

Amber comes up in a lot of the biographical materials here (although substantial work set in and about Amber per se will be in the sixth and final volume). Lots of other things are going on with Zelazny besides Amber (although it is looming ever larger) although I now really do see how weirdly backwards I got exposed to his career. The Zelazny of the 60’s and 70’s, writing the short fiction and mostly singleton novels is a different beast than someone working on what would ultimately become a 10 book series. I started with Amber and worked forward and back, but for readers who had been following “all along”, I can now see their point, and their unhappiness, as to how Zelazny’s career turned out.

And this is something Zelazny himself addresses at one point, talking about how his career is always about him trying new things, new forms, new ideas, and new experimentations. Zelazny is a writer who was always trying to “find new boundaries, only to break through them”. The Amber series itself can be seen of a piece with that, but more substantive discussion of Amber should wait until the sixth volume. Let’s put a pin in that, for now.

But speaking of experimentations, one of my favorite Zelazny works, and one where he was challenged and then challenged himself, is one of my favorite Zelazny stories, “24 views of Mt. Fuji by Hokusai”. This is a very atypical story for Zelazny in that it has a female protagonist at its center. It’s an interestingly crafted tale, with our main character Mari traveling to various viewpoints of the mountain on her own personal pilgrimage, and slowly revealing how and why she is doing it, and the force opposing her. Along the way with the technological entity that she faces, we get all sorts of literary allusions (including to the Mythos), a couple of different SFF styles of story and much more. It’s wildly ambitious and succeeds on every level, and it was a welcome friend to read again.

We also get the pre-novel finale set of Dilvish stories here, as well. I can well see, after reading Devil and the Dancer, Garden of Blood, and the eponymous Dilvish the Damned just why Zelazny at this point decided to write The Changing Land and finally have Dilvish have his confrontation with Jerelak after all. The stories do not tire and do not get old, but in an aggregate, after a while, I could see why Zelazny would wonder “Well, when IS he going to catch his white whale, or die trying to do so?” I do think that Dilvish has unfairly not been part of the genre conversation of sword and sorcery (The famous Appendix M of the 1e Dungeon Master’s Guide mentions Jack of Shadows and Amber, but not Dilvish specifically. A missed opportunity there by Gygax, I think). I do think that some OSR game out there could be inspired by this set of Dilvish the Damned stories and run with some of the ideas, here.

There are a number of shared universes that intersect with Zelazny’s work at this point. This is no surprise because the 1980’s are the height of the shared universe trend in science fiction and fantasy. It’s nothing new for Roger, of course, Zelazny has always been collaborating, as we have seen. Here we get a small boomlet of them. We have a story in Fred Saberhagen’s Berserkers universe. We get a Niven Magic Goes Away story set in the modern day. I’d read the Magic Goes Away story (“Mana From Heaven”) and it is an old favorite of mine. I don’t previously reading the Berserker story. (“Itself surprised”). This was, of course, another clever Zelazny story playing with the premise.

And then there is of course, the one that is still ongoing, and that is George R. R. Martin’s Wild Cards. Zelazny had missed the Thieves World saga and he had regretted it. So when Martin asked him to join Wild Cards, he did with both feet. Famously, Zelazny created one of the more memorable, and potentially powerful characters in the Wild Cards verse, but circumstances meant that only a couple of those stories (by Roger) ever gotten written. This book collects “The Sleeper” and “Ashes to Ashes”.

“The Sleeper” introduces us to Zelazny’s character and his origin story, and slowly lets the character and the reader figure out his superpower. As it turns out, Croyd Crenson is a teenager who gains the ability to randomly change his powers, appearance, status as an Ace or a Joker, and even his personality between cycles of what amounts to hibernation. This makes him potentially the most powerful character in the entire Wild Cards verse, and he has an enormous flexibility as a result. He loves his family, and wants to be there for them, and is afraid of them slipping out of his life through his involuntary hibernations. He’s functionally immortal, as a result, but it is an often pathos filled immortality. While others have run off with the character in the two decades since, these two stories give us the original and undistilled version of Croyd, who he is and what he does.

It should be noted, fittingly, that we get a remembrance of Roger Zelazny as a person and his work from George R.R. Martin himself. I find, personally, reading these as these volumes march toward his too-soon end of his life, that I feel them becoming more poignant and melancholia-inducing in me. This is not Martin’s intention, mind, but something I bring to the series and to these remembrances. We also get a lovely remembrance from Melinda Snodgrass, as well.

In addition to those, we get a good assortment of other odds and ends here. Outlines for COILS, which he would eventually collaborate on with Saberhagen. An outliner and a bit of a world document for his Alien Speedway shared world series, which sadly and tragically never was completed. A good selection of poetry, and, once again, a biography of the relevant period of Zelazny’s life covered by the publication of the stories. As you might have guessed, given his smaller short story output, this volume’s essay on his literary life by Kovacs covers more chronological years, 1982 to 1990, than in any of the previous single volumes (except for volume one, of course, which goes from his birth to 1961).

With just one volume left to go, I look forward to, in the sixth and final volume, completing the literacy legacy and history of my favorite SFF writer. And, oh yes, “completing the cover art” that is spread across the volumes of this series.

Stay tuned.