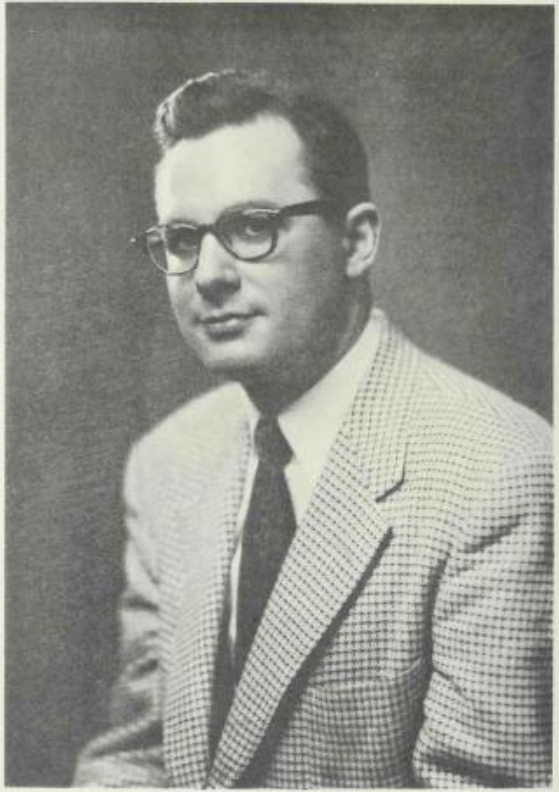

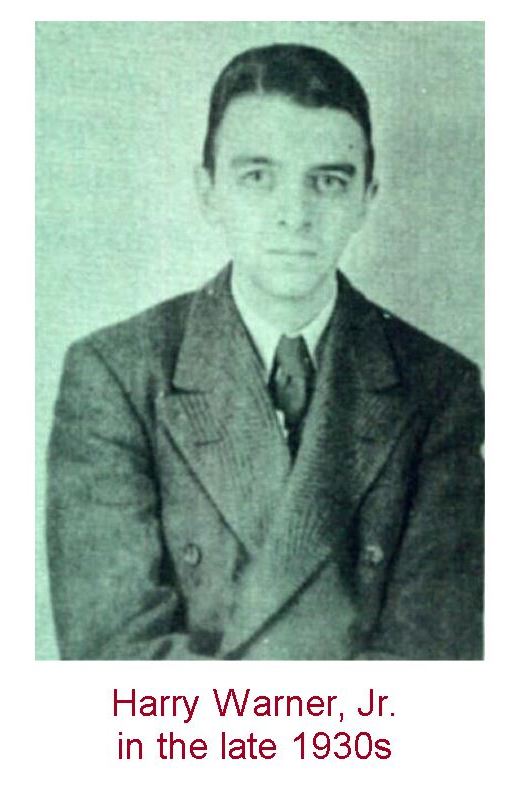

By Rich Lynch: Today we celebrate what would have been the 100th birthday of Harry Warner, Jr., who was perhaps the best-known stay-at-home science fiction fan of all time.

Harry was a lifelong resident of Hagerstown, Maryland and a fan for most of his life; his fan activities began in 1936, when he was in his early teens, but by then he had already been a science fiction reader for several years: “My father got a couple of Jules Verne’s novels from the library for me to read [and] I read a little science fiction in the Big Little books, which were popular a long, long time ago. But I didn’t discover the prozines until 1933 – I bought my first Amazings and Wonders in that year.”

The path that Harry took into fandom was via the prozines. When he was 13 years old, he wrote a letter to Astounding’s “Brass Tacks” letters column, printed in the October 1936 issue, which mentioned that he would like to “correspond with someone of my own age or a little older”. Soon afterwards, he received about a dozen letters as well as a few fanzines (called ‘fanmags’ back then) in response, and began a letter exchange with some of the people who had written to him. One of these was James S. Avery, a fan from Maine, who convinced Harry they should co-edit their own fanmag, and in November 1938 the first issue appeared. This was Spaceways, a general interest fanmag which became one of the best fan publications of the pre-war years.

Spaceways was not destined to be a collaborative effort – it turned out that Avery never did contribute any material or effort to the publication so he was soon dropped as co-editor. As for Harry, it turned out that one of his talents was in persuading good writers to contribute to Spaceways; this included such notables as H.P. Lovecraft, Jack Williamson, Bob Tucker, Fred Pohl, Forrest J Ackerman, Sam Moskowitz, and Robert Lowndes. Harry also took great pains to keep Spaceways (and himself) above the fan politics and feuds that were endemic to the fandom of the late 1930s and early 1940s. By doing this, he made many friends and very few enemies.

Harry gained a reputation in fandom as ‘The Hermit of Hagerstown’, this from his reluctance or inability to travel far from home. As a result, he was frequently visited by those who were passing through the region on their way to or from various fan gatherings. One of these, in 1943, was the notorious fan freeloader Claude Degler, whom Harry described as actually behaving like a gentleman, but: “He left Hagerstown without getting into my home, an accomplishment for which I have never been sufficiently recognized.”

Over the years, Harry actually did leave Hagerstown to attend a few science fiction conventions, including the 1971 Worldcon where he was the Fan Guest of Honor. He was never very happy with the large crowd scenes, though, preferring the written word as his way of communicating with other fans. In the last decades of his life, he limited his contact with other fans to groups of two or three at the largest, so if you wanted to meet him you had to go visit him in Hagerstown.

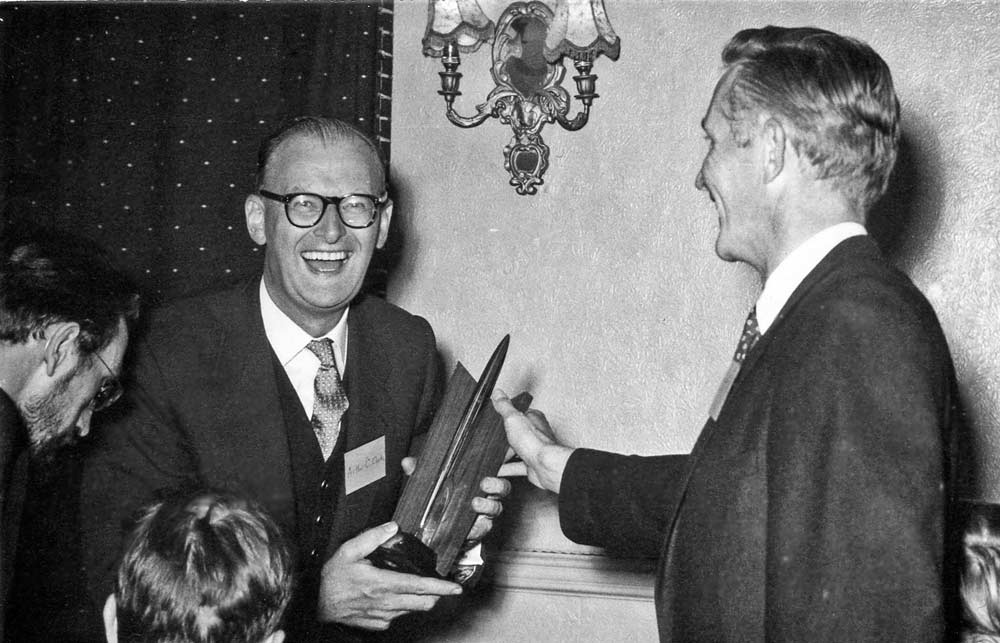

All of his fanac then was done from home, either by publishing fanzines, writing articles for other fanzines, or as a correspondent. His prozine letterhack days were pretty much over by the time he became a fanzine publisher, but he remained a prolific letter writer for the rest of his life, usually in response to the myriads of fanzines he received in the mail. Harry always found positive, constructive things to say about even the most abysmal of crudzines, and it was always a badge of honor for a fanzine publisher to include a Harry Warner letter of comment in the Letters Column. Many volumes could probably be published of the entertaining letters he wrote to fanzine publishers; at least partly for this prolificacy he was voted the Hugo Award for Best Fan Writer twice, in 1969 and 1972, winning out over such notables as Walt Willis, Terry Carr, and Susan Wood.

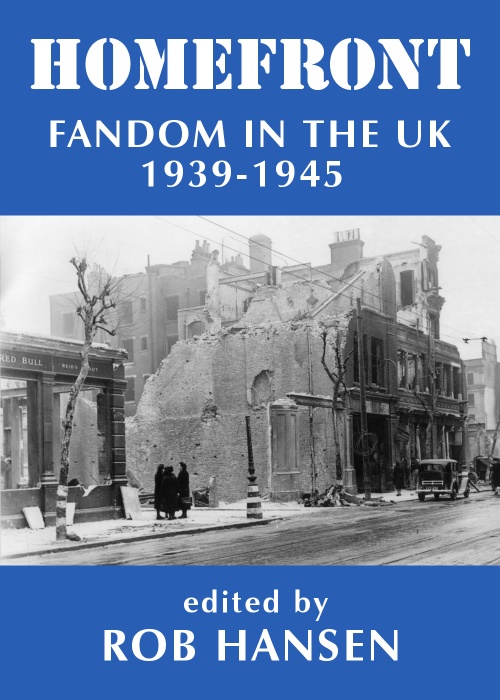

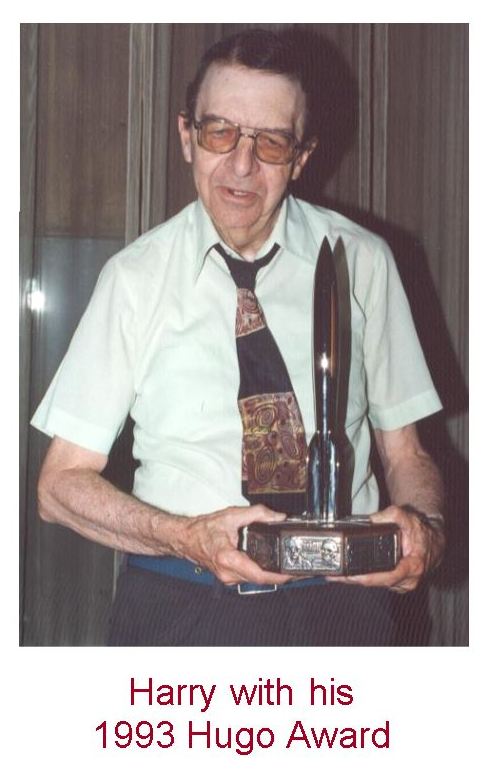

Harry also received one other Hugo Award, in 1993, for Best Non-Fiction Book. His large accumulation of fanzines provided him a resource from which to research the fandom of the 1940s and 1950s, and resulted in two books that he referred to as “informal histories” – All Our Yesterdays (Advent, 1969), about fandom of the 1940s, and A Wealth of Fable (SCIFI Press, 1992), about 1950s fandom. The Best Non-Fiction Book Hugo did not exist in 1970, or both books would likely have won the award.

Harry’s influence as a writer and historian on fandom is huge, and not only in the United States. Noted Swedish fan and writer John-Henri Holmberg wrote that: “What struck me about [Harry’s] letters, as well as his many fanzine essays, was his reasonableness, his sense of proportion, his quiet humor and good sense. In many ways, I suspect that Harry Warner was the ideal fan, in the sense that he managed to avoid both the wild-eyed fanaticism and the angry disillusionment which devour so many of us. He could see both sides to most conflicts, but even more importantly, he could also see that neither was particularly important.”

Harry leaves behind no relatives; only his writings survive him. And even though he was a lifelong bachelor, he was as much a patriarchal figure as has ever existed in science fiction fandom. Not long after Harry’s death in February 2003, fan historian Moshe Feder noted that: “[Harry] may not have any surviving blood kin, but we are his family, and his proper mourners, as is any faned anywhere who will never again receive a Harry Warner letter of comment.” And he’s right.