By Steve Vertlieb: There is a contemptuously lazy notion that Silents in theaters are anything but golden, and that black and white cinematography is somehow impotent and ineffectual. Contemporary audiences, jaded by three dimensional, digital technology and a ravenous appetite for fast paced action, have callously abandoned nuance and subtlety in favor of instant, if mindless, gratification. It’s somehow more comforting to dismiss films lacking modern sensibilities and technology than to place one’s self in the cultural context of the time in which they were conceived and filmed. The concept is as plausible as dismissing historical events and psychology because they occurred in a distant context. Art is no less valid because it was created in a “foreign” culture. What passes for shock value in present day entertainment may well become valueless five years down the road. Time doesn’t necessarily diminish the import of art’s original power or significance, nor should it. Hitchcock’s Psycho was a groundbreaking shocker upon its initial release, and remains a masterpiece of subtle horror. However, it isn’t uncommon for jaded collegiate audiences to jeer and ridicule sequences that, after nearly half a century, have understandably become copied, imitated and clichéd. That shouldn’t diminish the film’s importance or contribution to the popular culture and mystique.

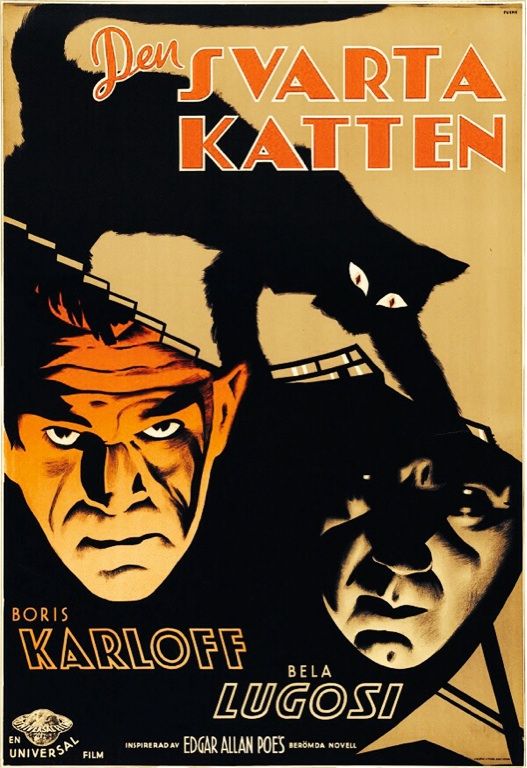

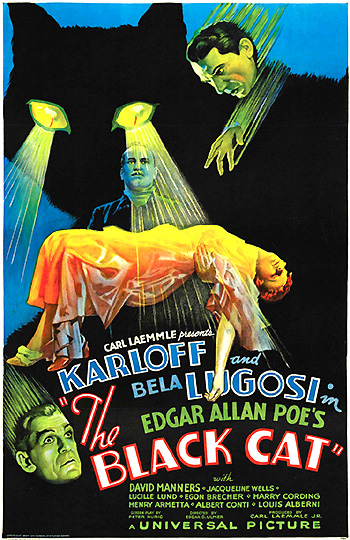

The Black Cat, filmed prior to the advent of the infamous Hollywood Production Code was, for its time, a lurid and perverse cinematic revelation. That this macabre melodrama continues to fascinate modern audiences after nearly ninety years is a tribute to its hypnotic treatment and charm. Directed by Edgar G. Ulmer, who seemingly did little else of serious consequence in his career, Cat is a sublime experience and remains among a small handful of the most noteworthy horror films of the period. Along with MGM’s The Mask of Fu Manchu, The Black Cat is a delirious excursion into sadism, satanism and drooling sensuality. It’s also a supreme surrender to the prurient fantasies of a sexually repressed and frustrated American populace, drowning in the Victorian niceties of naïve drama and extraordinarily silly comedies proliferating during the period.

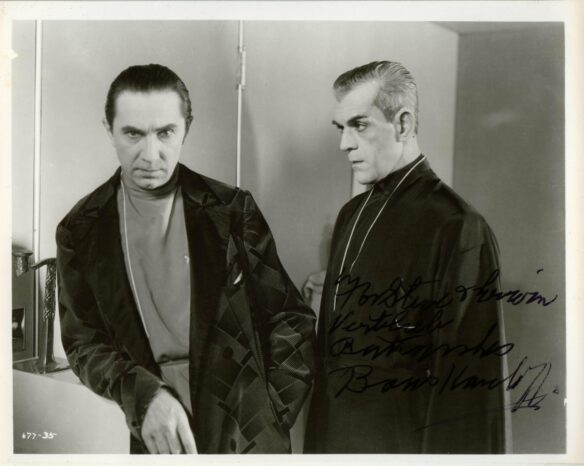

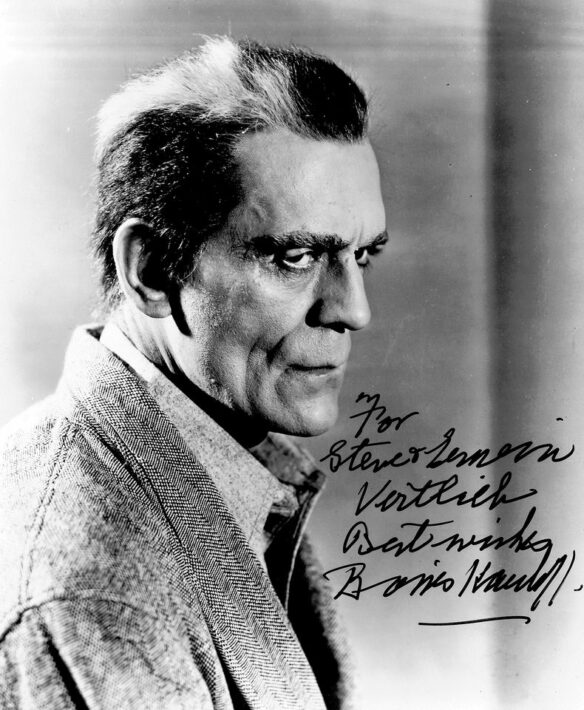

The Black Cat is a dark, Germanic descent into torture, depravity and virgin sacrifice that, except for a brief and unfortunate comedic interlude that Universal felt somehow compelled to insert midway into the picture, perhaps to lighten the intensity of its surrounding sequences, remains one of the most unforgettable horror films of the golden era. It is also the single most effective pairing of the studio’s acclaimed titans of terror…Boris Karloff and Bela Lugosi. As in the aforementioned Mask of Fu Manchu, Karloff subtly conveys the brooding intensity of evil he so ably mastered throughout the decade. Like his brilliant portrayal of Ardeth Bey in The Mummy two years earlier, his demonic Hjalmar Poelzig is a cold, calculating instrument of devilish determination, a vile, vicious sociopath whose obsessive lust for domination enslaves everyone within his demented sphere of demonic influence. Without the slightest hint of guilt, conscience or remorse, he imprisons his once closest friend…steals and marries his bride…beds and weds their innocent child and, later, cruelly murders her when his friend returns from years of incarceration, discovering the unholy deception. His smile, upon welcoming unwelcome guests to his chateau, is bone chilling…a thinly masked sadistic anticipation, darkly reminiscent of a carnivorous spider, awaiting unwitting insects entering his veiled and deadly web. Poelzig is an unrepentant hedonist, a grinning cobra slithering across a corrupted paradise, whose personal desires, gratification and pleasures come at the expense of all who tragically stand in his way.

Bela Lugosi, still at the height of his all too brief success, convincingly offers one of his finest, most passionate and dramatically intense performances as Dr. Vitus Werdegast, a deeply scarred and broken being returning from the graves of his martyred comrades…a walking skeleton obsessed by thoughts of revenge against the maniacal martinet who betrayed his people. He is a grim, yet pathetic soul…a vengeful somnambulist whose one remaining goal in life is to eradicate from the Earth the monstrous machinations of the Judas priest of the black arts who murdered his heart. His anguish at discovering the murder of his daughter is nearly too painful to watch. While Lugosi’s performance is among his best, one cannot help comparing the career paths taken by these titans of terror from the golden age. Lugosi gives it his all, and yet his performance seems to foreshadow the unfortunate series of choices and events that would soon diminish his stature and popularity. His was a raw talent that, perhaps, needed nurturing from better agents and directors than he encountered, while Karloff seemed to better understand and underplay his own gifts as an actor. Subtlety of performance may have been the key to Karloff’s longevity, while Lugosi’s flame blew, unrestrained, in its raging intensity until, at last, both the actor and his artistry had been consumed and dethroned. Lugosi’s artistry quickly lapsed in self parody and humiliation before he fully understood the rapid, unalterable decline of his once proud reputation and career.

The Black Cat, while loosely based upon a premise by Edgar Allan Poe has, of course, little to do with that author’s work or imagination. Like the Roger Corman/Vincent Price collaborations that followed decades later, this is an original work merely attempting to capitalize on Poe’s reputation and persona. Having said that, the film is nonetheless a revelation, and as fresh today as when it was filmed in 1934. The supporting players have little to do other than stand around and react to the sublime hysteria of their imposing co-stars. David Manners offers a characteristically bland performance, a dramatic counterpoint comparable to the comedic, yet clueless Margaret Dumont in the Marx Bros. pictures. Perhaps it was Ulmer’s instruction to simply get out of their way, but Manners seems mere window dressing to the drama and characters unfolding frantically about him. Jacqueline Wells, later Julie Bishop, fares somewhat better as Manners’ wife, and the sensual object of Karloff’s lust and carnal desires but she, too, is ultimately consigned to mere set decoration. Both the camera and direction are focused obsessively upon the ensuing battle of wills brewing between Karloff and Lugosi, representing damnation and hope.

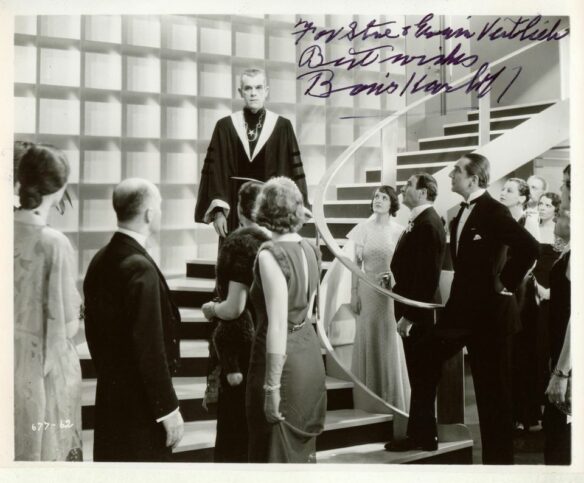

The Black Cat’s startling freshness is also due, at least in part, to the astonishing set decoration by Art Director Charles D. Hall. The Art Deco structure built by Engineer Poelzig upon the bloody foundation of the fortress he commanded and betrayed, Fort Marmaros, is eerily reflective of the ultra modernist architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright. The Satanist’s castle is a wondrous amalgamation of light and shadow; on its surface a bright, visionary world’s fair of excitation and imagination while, below the bright promise of tomorrow lies the deadly, intricate catacombs of a darker world adorned with cells and heinous chambers of torture and depravity. Lights in the upper structure appear to come to life as if by will alone, as in Karloff’s startling introduction, rising methodically from sleep, much as “Nosferatu” rose from his coffin in Murnau’s 1922 UFA production of Dracula, aboard the vessel transporting him back to England to feed. He is a vile, predatory creature, feline by nature, accursed by circumstance and fate, stalking unwary innocents as a hungry rodent creeping along the cobwebbed catacombs of his grotesque chambers of torture and damnation.

As in many of Universal’s early horror films, music plays an intense, integral part in the calculated gloom gradually intensifying the brooding production. The studio borrowed heavily from Tchaikovsky, Beethoven and Franz Lizst. The film is frequently swallowed by wall to wall music, drowning its victims in somber sacrament, while its overpowering adaptations add immeasurably to the suspense, moodiness and frenetic flow of its bizarre climactic sequences. Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony morosely illustrates Poelzig’s tour of the catacombs for his former friend, while Lizst’s Piano Sonata in B Minor accompanies the breathtaking, roller coaster action that thrillingly paints the Grand Guignol finale. The lower catacombs are littered with magician’s tubes encasing the preserved remains of Poelzig’s former lovers, lifelike and morbidly displayed as part of a proud fetishist’s carnival sideshow…the sacrificial victims, perhaps, of his unholy cult, encased forever in fluorescent embalming tombs.

But now the moon has risen and Herr Poelzig has once again summoned the believers to his black church to offer another unfortunate bride to Satan in ritualistic defiance of civility and law. The remaining moments of the film are among the most insatiable of the period as Werdegast and his ineffectual compatriot (Manners) conspire to save his wife, presumably from a fate worse than death. Poelzig is carried to the torture chambers beneath the main structure of the honey combed castle by Werdegast’s loyal manservant where he is flayed alive on his own embalming rack. “Do you know what I’m going to do to you now, Hjalmar,” asks Werdegast in nearly sexual excitation. “I’m going to tear the skin from your body…BIT BY BIT.” Photographed in disturbing, brightly lit silhouette, Werdegast’s insane laughter splinters the soundtrack as Poelzig’s agonized writhing can be observed upon the opposing wall of the chamber. Frighteningly animalistic to the end, Poelzig’s death cries are more like a savaged panther than a human being in mortal torment. He is a decadent creature of the night, a cunning and ravenous vulture avenged by the contemptuous conspiring of his own deceit and debauchery.

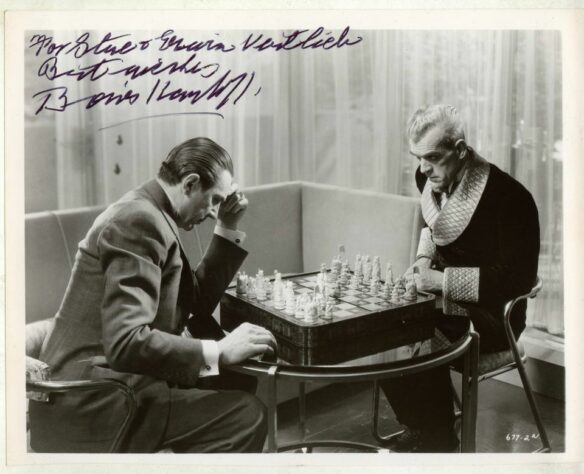

Part of the thoroughgoing depravity of The Black Cat is that while the secondary players add little to the structure of the film, the characters that they play mean even less to their malevolent hosts. Although Werdegast offers a hint of scarred nobility in sacrificing himself, allowing his young companions to escape, his compelling obsession for revenge against the man who wronged him is his dominant, obsessively consuming concern. Peter and Joan Alison are merely an annoying diversion. He cares no more for their plight than Poelzig. Indeed, when Poelzig and Werdegast engage in a deadly game of chess which will, ultimately, determine whether young Alison and his bride survive the evening, neither foe is particularly interested in the bland conversation awkwardly devised by Peter. The Alisons are as meaningless to their adversaries as the pawns adorning their antique chessboard. Peter and Joan are truly inconsequential chess pieces, for all of this is ultimately a game to both Poelzig and Werdegast. When Peter attempts to use the telephone in order to call for a cab to transport them out of their Wagnerian dungeon he discovers, to virtually no one’s surprise, that the phone is dead. “Did you hear that, Vitos?” Poelzig leers with contemptuous delight. “The phone is dead. Even the phone is dead.”

There is more than a hint of Poelzig’s inner depravity, so brilliantly expressed by the subtleties of evil, masterfully conveyed in Karloff’s finely etched portrayal. His face is a treacherous mask, vaguely suggesting the quiet sadism and sexual perversion lurking menacingly beneath the surface of his grotesquely mocking smile. It’s astonishing, even by modern standards, to imagine the intensity of evil so devilishly consuming this dark, Faustian figure. Karloff, a genuinely kind and gentle soul away from the camera, possessed an uncanny ability to convert Jekyll into Hyde, summoning the inner demons slumbering beneath the mannered goodness awash within the human soul. In performance after performance, either as a malicious mummy awakened in modern Egypt, or as the deliciously vile Dr. Fu Manchu, Karloff could wrench an uncanny malevolence from the cultured pretense of mannered civility, and hide beneath its cloak before the rolling cameras. It is no mere accident that his name remains synonymous with cinematic evil so many years after his time, and passage, despite his own personal gentility and almost legendary kindness.

The Black Cat today continues to thrill and fascinate adoring admirers of both the film and its stars. It was an anachronism in its time, a bizarre transplant provocatively out of step with the tenor of the period in which it was filmed. Its brooding sadism, and perverse sexuality, have elevated the film from a standard assembly line potboiler to cult status among critics and adoring fans of the popular genre. With its frenetic pacing, breathtaking set design, haunting performances and boundless excitement, The Black Cat has admirably survived and surpassed its ambitions, becoming an exuberant and remarkably abstract artifact of cinematic antiquity.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Ah, yes, the ever-popular Kids These Days argument.

This sounds like a better movie than I ever had thought, aside from the fact that it seems to have little to do with Poe’s short story that its supposedly adapted from. I’m considering renting it on Amazon Prime in the next day or two. Thanks for sharing!

I remember seeing this film and being truly horrified. It was not what I expected, and I had no idea why it was so indelibly imprinted on my aesthetic. The house was the antithesis of the positive feeling that Deco usually conveyed. And the horror was, indeed, conveyed subtly. The only gore involved at all was the ending, and even that was underplayed. I was reminded of the use of shadow in “The Cat People.”

I don’t think the ‘kids these days’ argument is relevant here, though I did have a young man recently assure me that ‘nothing made before I was born has any significance.’ We have had a couple generations of people spoon fed the idea that if it is not new it is not worthwhile, and if it is new, no matter how lacking in quality, it must be bought immediately. That’s Fashion and Advertising. It was not very long ago that college literature courses taught how ‘bad’ Dickens was because the characters were not ‘realistic;’ meaning they did not wear grey flannel suits or spend their intellects worrying about their neighbors’ sex lives.

The people who bought pet rocks are getting gray now and getting arthritis.

Science fiction is going through that ‘everything old is irrelevant’ phase now: ironically, as people outside the field discover the quality of characterization, subtlety, and directness, of many of the Golden Age writers.

I really love Steve’s essays of tribute to things that may have been overlooked in the garish wash of over-adjectived advertising. Keep them coming, Steve! You are a treasure!

The moon did not rise, as Poelzig stated it was the “dark off the moon”

Pingback: 2024 Rondo Awards Nominees - File 770

Pingback: Pixel Scroll 2/28/24 Two Scrolls Diverged In A File, And I — I Took The One Less Pixeled By - File 770

Pingback: Pixel Scroll 4/12/24 One Pixel, One Scroll, One File | File 770