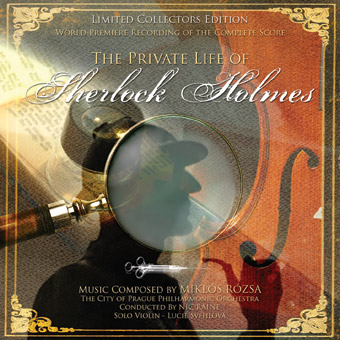

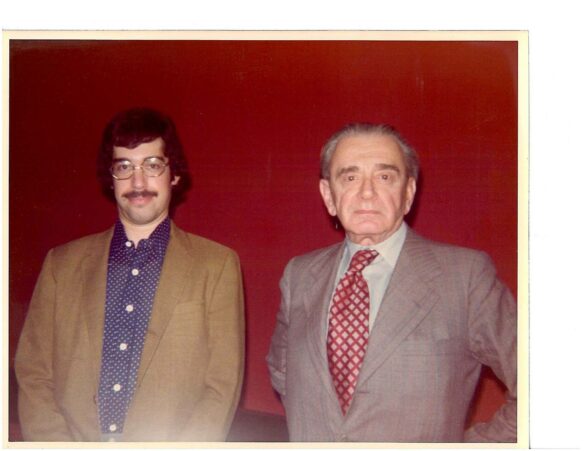

By Steve Vertlieb: In 2007 I was honored to become a part of the singular release of Tadlow Records’ World Premiere recording of Miklos Rozsa’s beloved motion picture score for Billy Wilder’s melancholy masterpiece, “The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes.”

Juliet Rozsa, daughter of the 3-time Oscar winning composer, and I were invited by Tadlow producer James Fitzpatrick to contribute liner notes to the spectacular CD recording conducted by Nic Raine and The City of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra, with rapturous violin solos by Lucie Svehlova.

This exquisite recording was recently re-released by Tadlow and, in honor of its recent reappearance in the film score marketplace, here are my original liner notes for this memorable tribute to Billy Wilder, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, composer Miklos Rozsa, and the world’s remarkable first consulting detective, Sherlock Holmes.

April 18, 2007 marked the centenary of Miklos Rozsa’s birth. Classically trained, the Hungarian émigré began his film career in 1937 with Knight Without Armour for Alexander Korda in England. Quickly establishing his own unique sound and presence in a crowded arena, Rozsa transformed his classical sensibilities into a richly individual voice within the motion picture community, composing one hundred ten scores between 1937 and 1982. No less an authority than Elmer Bernstein regarded Rozsa and Bernard Herrmann as the two greatest practitioners of symphonic film scoring in its long, distinguished history.

While still a student in Germany, Rozsa’s early works were already being published and performed. By the time he arrived in Paris in 1931 he had established a solid reputation as a serious composer. Composition, however, brought in little recompense and he was forced to teach in order to make a living. One night during a dinner conversation with Arthur Honegger, Rozsa was encouraged to try his hand at film scoring. Believing, somewhat innocently, that film music consisted solely of “fox trots,” Rozsa was astonished to learn that serious music was being written for the screen. Honegger suggested that Rozsa go to see a film production of Hugo’s Les Miserables for which he’d recently written the score. The experience was to change the young composer’s life, for here was a somber theatrical presentation with dramatic music, bringing the production vividly to cinematic life. Intuitively, Rozsa sensed that the new medium of sound motion pictures might offer him a forum in which to make a significant, artistic contribution.

A chance encounter with actress Marlene Dietrich led to a contract with England’s leading film studio, London Films, and the Korda brothers who presided over production. Knight Without Armour was the composer’s first assignment, followed by the stark, musical strokes of 1939’s The Four Feathers. Alexander Korda grew to respect Rozsa’s obvious talent and, despite the objections of Ludvig Berger, the film’s director, Korda replaced the Viennese operetta approach of German composer Oscar Strauss with the magical rhapsodies of Miklos Rozsa for London Films’ production of The Thief of Bagdad. The film premiered on Christmas day, 1940, both in Britain and in America and remains one of the most gloriously imaginative films ever made, rivaling The Wizard of Oz in its sumptuous presentation. The musical scoring by Rozsa, set to a visual tapestry of genies, wizards, flying horses and magically airborne carpets, is among the most wondrous of his career and a landmark in symphonic scoring for films.

The assignment in 1940 would be a fortuitous one for Rozsa. When war broke out in England, the cast and crew of the Arabian Nights fantasy was transported, not by carpet, but by plane to the United States in order to shoot additional scenes in the Grand Canyon to complete the picture. Rozsa fell in love with America and, when the production company returned to England, he decided to remain.

Rozsa had loved Rudyard Kipling’s stories since his boyhood, so when Zoltan Korda called upon his services once more to write the music for The Jungle Book, he was elated. The Jungle Book, while not in the same class as the earlier film was, nonetheless, a beautiful, haunting film, easily towering above its many remakes and incarnations. However, its most striking element remains Rozsa’s exquisite score. “Song of the Jungle,” his miraculous evocation of the dense foliage and its inhabitants, slowly awakening to the subtle nuances of a beguiling new day, has been recorded and performed numerous times by many of the world’s most prestigious orchestras.

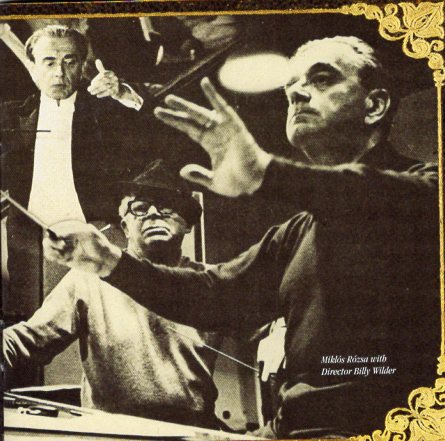

1943 saw the beginning of Rozsa’s legendary association and friendship with Billy Wilder. Wilder was preparing his second film, Five Graves To Cairo, for Paramount and had wanted Franz Waxman to write the score. Waxman, however, was unavailable and so Wilder turned to Rozsa. Wilder regarded Rozsa as an unknown quantity but told him that if he liked his work on this picture, that he might consider him for his next. Despite protests by Paramount that Rozsa’s melodies were dissonant and harsh, Wilder stood by the composer, demanding that his themes be incorporated into the finished picture. After the success of Five Graves To Cairo, Wilder remained true to his word, hiring Rozsa to write the music for his next picture at Paramount, Double Indemnity (1944). His searing, powerful themes dominated the classic story of murder and marital betrayal, becoming the most celebrated of Rozsa’s many Cinema Noir scores. Wilder and Rozsa teamed yet again in 1945 for the brutally honest The Lost Weekend, the first mainstream film to address the nightmare of alcoholism in America. Rozsa’s triumphant score brutally captured the fear and paranoia of a world lost and drowning in “The Bottle.”

Rozsa won his first of three Oscars that year for Alfred Hitchcock’s Spellbound. Though Hitchcock would never work with the composer again, “The Spellbound Concerto” eclipsed the picture it derived from. The orchestral suite has been performed and recorded countless times, and remains the composer’s most famous and identifiable work. Rozsa went on to win Oscars for George Cukor’s A Double Life in 1948, and William Wyler’s majestic remake of Ben-Hur in 1959. After creating the stark, Brave Noir World of the forties, Rozsa enjoyed his richest, most creative output during the Nineteen Fifties and early Sixties with his Biblical epics, culminating with both the magnificence and sweeping grandeur of Ben-Hur, and his thunderous, passionate rhapsodies for Samuel Bronston’s El Cid (1961).

Billy Wilder re-entered Rozsa’s life in 1970. One of Wilder’s preferred methods of relaxation while preparing his film scripts was to listen to Rozsa’s “Concerto For Violin and Orchestra”, commissioned by Jascha Heifetz in 1956. The concerto was among the director’s favorite pieces of music, and he promised Rozsa that one day he would incorporate its themes into a film.

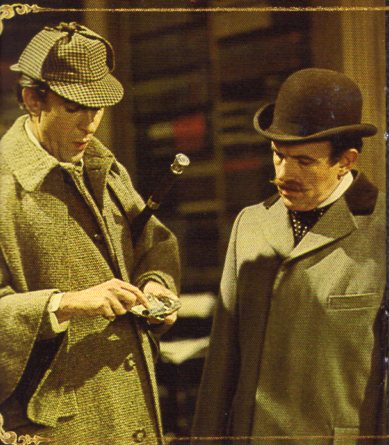

That film would be, perhaps, his most personal…The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, a three-hour extravaganza designed as a final masterpiece from one of cinema’s most eloquent story tellers. Rozsa was asked by Wilder to adapt his concerto, and write new thematic material for this atypical dissection of fiction’s most famous consulting detective. Wilder’s Holmes was a brittle, sensitive, and lonely genius whose purity of heart had been shattered irretrievably by a lost, tragic love, subtly alluded to in the enigmatic screenplay. United Artists, under new management, had little understanding of Wilder’s brilliance, and botched the film’s advertising campaign, promoting the picture as a comedic send up of Conan Doyle’s creation when, in fact, mere traces of burlesque graced the production. Wilder, himself a renowned wit and raconteur, masked his own fragile insecurities with sophisticated direction and writing. He identified with Holmes’ inner doubts and fragile bravado. United Artists castrated Wilder’s final “cut,” trimming the picture by a third and eliminating several of its most charming vignettes. Wilder was devastated by the callous emasculation of his work, and returned to the screen only infrequently after that. The critics were unresponsive to the picture, while the public mostly stayed away. The restoration and preservation of Wilder’s original cut remains one of the highest priorities of The American Film Institute, and yet the final release print of Wilder’s masterwork, though butchered, is justifiably regarded as one of the director’s most beautiful films. Here, for the first time, is presented the exquisite and thrilling score…recorded in its entirety for the one hundredth anniversary of this legendary composer’s birth…the World Premiere Recording of Miklos Rozsa’s score for Billy Wilder’s THE Private Life of Sherlock Holmes.

++ Steve Vertlieb, January, 2007

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Miklos Rozsa also scored Harryhausen’s “Golden Voyage of Sinbad.”

Some of the best music of the 20th and 21st centuries was written for movies.