Worldcon Wayback Machine Introduction: Thirty years ago this weekend ConFrancisco, the 1993 World Science Fiction Convention, was held in San Francisco, California. I thought it would fun to compile a day-by-day recreation drawing on the report I ran in File 770, Evelyn Leeper’s con report on Fanac.org (used with permission), and the contributions of others. Here is the third daily installment.

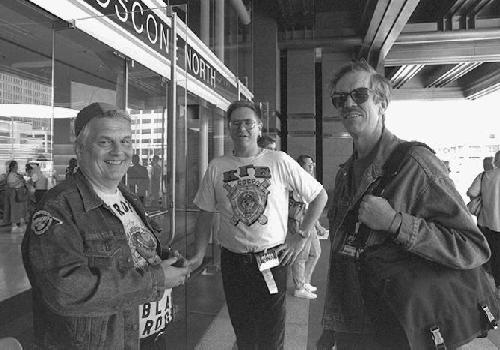

The Worldcon was held in the Moscone Convention Center, ANA Hotel, Parc Fifty Five, and Nikko Hotel.

[Mike Glyer] Art Show: Art Show director Elayne Pelz preferred to use her large area within Hall D by creating 15-foot aisles than by filling it with the maximum possible number of hangings. This decision became controversial as people tried to explain their subjective dissatisfaction about the average quality of the artists’ entries. Mike Kennedy, in The NASFA Shuttle, thought, “The quality was more uneven than I recall from past shows. There seemed to be a noticeable proportion of mediocre fan art and there was certainly a lot of media-oriented art (mostly Trek of various vintages.) The good stuff that was there was very, very good.” Many shared Stu Hellinger’s view: “There was less really memorable art at this con than any Worldcon I’ve seen in years.” Unlike Hellinger, the others blamed their frustration on the vacant space in the display area. John Pomeranz commented, “I was disappointed to see how under-utilized the art show space was given the number of excellent artists who were turned away.”

Elayne agreed that ConFrancisco’s art show with 280 panels was smaller MagiCon’s show of 320 panels, but added that was a deliberate decision. She fixed the size of the show at 280 to preserve a certain ratio between the number of panels and projected attendance, to give the artists a decent chance to make some money. This was a controversial policy in 1993 because attendance at ConFrancisco was projected to be much lower than at MagiCon, so Elayne’s ratio dictated significantly fewer panels. Fifty artists who wanted to show work could not get panels under to this policy.

John Lorentz, past Westercon chair, responded, “Yes, there was room for more panels — but that doesn’t necessarily mean that we’d have seen more good art, nor that the individual artists would have sold as many pieces. …Many cons limit the number of dealer tables sold for the same reason.”

Several worthy ideals conflicted in this case. An average fan wants the largest and most visually interesting art show possible, and cannot conceive of any reason for limiting it apart from laws of Newton and the fire marshal. Artists, like dealers, want equal access to the Worldcon marketplace for business reasons: prior to the con they may claim they don’t care how many other panels or tables there will be, as long as they get in. Afterwards, both artists and dealers are prone to complain that so-and-so was a bad con if they don’t make very much money. For years a couple of dealers have told me that having 300 tables at L.A.con II was a bad policy because the people in the back of the room “didn’t make any money.” Yet nondealers tell me it was the best dealer’s room ever.

As to what was noteworthy in the show, I really enjoyed the exhibit of work by Hugo nominated artists, including James Gurney’s Dinotopia and the Teddy Harvia-Peggy Ranson black-and-white cover for File 770’s 100th issue. Michael Whelan’s section included a black-and-while oil preliminary for the cover of Mike Resnick’s novel, Ivory, that the author said he liked much better than the version that finally appeared.

A very humorous artwork, Diana Pavlac’s favorite piece, was a model of alien beings walking through a sf convention art show. The dollhouse-scale artworks mimicked the range of subjects and styles at a real worldcon, and of course the alien observers were pleasingly bizarre and colorful.

Kathryn Daugherty believes, “[The] real thrill of a worldcon art show is to see cover art; upclose, personal, and live. If you compare art reproduction to the original image, there is nothing like the real thing. Plus the fascination of seeing more than one piece by a professional artist at one time. I like Jim Burns’ work and I thought it was wonderful that he had so many pieces in the show, some from quite a long time ago and some recent. …Obviously this is a contrarian opinion, but since the number of interesting pieces (and even the number that sold) is higher than the expected rate if you strictly followed Sturgeon’s Law, I’ll stand by my opinion that this was a good art show.”

It was also a financial success, with $113,000 in sales, compared to $96,000 at MagiCon. The record is still $125,000, set at L.A.con II in 1984. (Art Show statistics don’t count income from ASFA Print Shop sales or panels used for non-sale displays.)

ART SHOW AWARDS

Best of Show: Bob Eggleton—Orcaurora

Best Artist: Michael Whelan

Judges’ Awards:

- Alicia Austin—No Two Alike

- Jim Burns—Aristoi

- David Cherry—The Goblin Mirror

- James Gurney—Garden of Hope

- Jody Lee—World’s End

- Frank Liltz—Riding the Starstream

- Lubov—Web

- Clayburn Moore—Celestial Jade

- Janny Wurts—Curse of the Mist Wraith

[Mike Glyer] Panel: Does Fandom Need a 12-Step Program? (Saturday 10:00 a.m.) [Panelists:] Scott C. Dennis, Janice Gelb, Mike Glyer, David Levine. [Topic:] “Friends of Joe P. Is fandom an addiction or hobby? Is it possible to just say no to fandom? Can we make it, one con at a time?”

Just in case it does need one, Eve Ackerman came up with these twelve steps: “(1) We admitted we were powerless over fandom — that our lives had become unmanageable. (2) Came to believe that gafiating could restore us to sanity. (3) Made a decision to turn our lives over to the care of people who had no idea what ‘SMOF’ meant. (4) Made a searching and fearless inventory of our fanac. Cleaned out the spare bedroom taken over by zines and back issues of F&SF. (5) Admitted to all our various con comms and OE’s the exact nature of our wrongs. Told them firmly that we wouldn’t run the huckster room again.

“(6) Were entirely ready to admit that FIJAGDH. (7) Humbly asked our bosses not to fire us for using the office photocopier, fax machines and express mail envelopes for our zines. (8) Made a list of all persons we had harmed through fanac and became willing to make amends RSN, providing that it doesn’t embroil us in more fan feuds. (9) Made direct amends to such people wherever possible, understanding that our chances of becoming TAFF or DUFF winner were now really remote. (10) Continued to take personal inventory and when we were wrong promptly moved away from the keyboard so we wouldn’t write about it and e-mail it out. (11) Sought through prayer and meditation to improve our conscious contact with non-fen. Read the Wall Street Journal, People and the National Enquirer so we’d have something to talk about. (12) Having a spiritual awakening as a result of these Steps, we tried to carry this message to others (insofar as it doesn’t involve BBS e-mail, apas, fanzines or cons) and to practice these principles in all our affairs.”

[Evelyn C. Leeper] Panel: The 100 MPG Engine: Legends That Will Not Die (Saturday, 10:00 a.m.) [Panelists:] Gregory Benford (m), Rick Cook, Steve Howe, Daniel L. Marcus. [Topic:] “’Suppressed technology.’ How do stories get started about cars that run on water, carburetors that allow 90 miles per gallon, and anti-cancer drugs made from common household chemicals?”

Well, I had expected a panel talking about technological “urban legends” but instead got one talking about how some of these “wildcat” ideas are real, but not marketable. For example, there are cars that can get eighty miles per gallon of gasoline, but they are undrivable under street conditions: they have no acceleration and constantly backfire. The Wankel (rotary) engine was another idea that failed on its own merits (rather than being suppressed); its fuel consumption was high (about fourteen miles per gallon) and it generated a lot of pollution because the seals were never perfected. (So just what was its advantage supposed to be? I can’t even remember.)

And then there was the nuclear-powered airplane. Oh, it would have worked, but sufficient shielding around the fuel would have made it too heavy, so it would only work if you had a crew that didn’t mind getting fried by the radiation, and it would also irradiate all the land it flew over. But the designers had thought of what to do with it when they were done–they would land it in Antarctica and use that as a nuclear-waste dump. (Luckily, this idea never got off the ground–so to speak.)

And remember SDI? This was described by one of the panelists as a “Fast Eddie” Teller idea, and eventually people concluded that it also had more flaws than virtues.

Other ideas probably were more workable, but not wise. Small nuclear bombs, weighing less than a hundred pounds complete, could be used by guerilla forces in Europe after it was overrun by the Soviets. Well, that was the original idea, but someone apparently realized that given the state of the world, having bombs this small that people could smuggle around was a really bad idea.

On the other hand, the L5 solar power satellite sounded crazy initially, but turned out to be a good idea.

But why do we believe all the fantastic stories of great inventions and discoveries, even when they are bogus? (Cold fusion comes to mind, naturally, although it was pointed out that the whole cold fusion thing did teach us a lot about sub-quantum states.) Well, for one thing, we want to believe them. Someone (Thomas Hardy, I think) wrote a poem about how there was a legend that on Christmas Eve, animals could talk, and said at the end that he didn’t believe it, but that if someone say it were happening in the barn, he would go, “wishing it might be so.” Certainly there must be some explanation of why people believe what they read in the Weekly World News.

Howe said that one problem is that science nowadays is all done as “big science.” His analogy is that it’s as if the government of the 19th Century deciding to explore the West with an army that marches together as a unit instead of with lots of small exploration and settlement parties. So the “small science” is left with more than its share of cranks. Benford said that his school (University of California at Irvine), the crank calls are doled out to the various professors. Most fall into two categories: 1) “What was that thing I saw in the sky last night?” and 2) “I have a new energy source that will save the world.” Howe asked whether Benford wouldn’t be sorry if he rejected someone who turned out to be a genius. “Would I be sorry? Yes. But what are the odds?”

One panelist noted that he is more bothered by stories of suppressed cancer cures than stories of suppressed energy sources, because the latter are usually just humorous, but the former touch people personally in matters of life and death. Someone asked about Linus Pauling’s theories about anti-oxidants, and the response was that since he was still walking five miles a day at age 92, they shouldn’t be written off too quickly.

One audience member noted that the panelists were referring to crackpots as “he” and asked if they had ever run across any female crackpots, to which Benford responded, “I’ve dated some.” Cook noted, however, that female crackpots seem to be more conspiracy theorists than scientists.

One problem with the whole “suppression” and “conspiracy” theory these days is that suppressing an idea in the United States doesn’t do much about suppressing it globally. Of course, there is suppression here, but it is more from the Food & Drug Administration and liability laws than from any secret coterie. In addition (as was noted earlier) the public suppresses things by not buying them and hence driving them off the market. Most products represent a trade-off: you can get more miles per gallon, but only if you are willing to buy a smaller, lighter, slower car. Other products are monopolized (the example given was forceps, invented in the 14th Century but monopolized for a hundred years by one family).

Along the lines of the suppression theories, I recommend David Mamet’s Water Engine, recently made into a movie for TNT.

(There was a certain irony to the fact that this was opposite the panel on Nikola Tesla, and in fact, there was odd sounds coming over the public address system that may have been coming from the demonstrations associated with the other panel.)

[Mike Glyer] Digby Fanwriting Gets Rare Hardcover: Along Fantasy Way, an anthology of fanwriting by ConFrancisco guest of honor Tom Digby, was available for purchase at the Worldcon. The 58-page collection, edited by Lee Gold, featured illustrations by Phil Foglio, Brad Foster, Teddy Harvia and Kaja Murphy. There were samples of Digby’s fanciful, ironic, stand-the-world-on-its-ear humor from the past three decades.

His kaleidoscopic Apa-L zine title (“Probably Something”) serves as an appetizer: “PROBABLY SOMETHING but not Combining Voodoo and Acupuncture for Remote-Control Healing”; “PROBABLY SOMETHING but not The Entire Staff of a Hotel Being Turned into Frogs During a Witches’ Convention.”

There are also brilliantly funny poems, too long to excerpt here. And there are many examples of Digby’s contributions to science: “Set up a Ferris wheel with a witch at the bottom and a princess on a special platform within easy reach of the top. Fill all the seats on the wheel with princes and start the wheel, with instructions that the witch is to change each prince into a frog as he goes by the bottom and the princess is to change them back as they go past the top. …Since princes weigh more than frogs, you should be able to use it as a perpetual (until the princes, princess, witch, etc., get tired) motion machine.”

[Evelyn C. Leeper] Panel: Language: Barrier or Bridge (Saturday 1:00 p.m.) [Panelists] Thorarinn Gunnarsson, Gay Haldeman (m), Michael Kandel, Yoshio Kobayashi, Maureen F. McHugh. [Topic:] “Translation helps bring works to audiences who can’t read them in the original, but how are works affected when the words and the grammar change?”

The panelists had some commentary on why they thought they were chosen for the panel and what their real qualifications were. Gunnarsson said, “I’ve never done translation work, but I’ve been annoyed by enough of it.” McHugh said that she though she was on the panel because so many of her stories were about China that people thought she spoke Chinese. She claimed she didn’t, but it was clear from things said during the rest of the panel that her Chinese was certainly more proficient than most folks’ second languages are.

The first, and perhaps obvious, point made was that translating is not a one-to-one thing. You can’t sit down with a dictionary and a grammar and hope to get any sense of what the original meant in the translation. Kandel noted, for example, that objects (nouns) in some languages can have gender, which can lead to interesting word-play if these objects are animate. If “wall” in Spanish is masculine (“el muro”) and in German is masculine (“der Wand”), then if a Spanish author writes, “The wall said to her, ‘Wake up, dear,'” that will have a different connotation than it would in German (or in English). (I should note that going in the other direction, there is a masculine word for wall in Spanish (“la pared”), so that translator would have a way out.)

Kobayashi said that in Japanese there is no swearing (or certainly not the variety we have in English), so translating strong language into Japanese can be a problem, particularly when the literal and figurative meanings of the words are both important. And often etiquette is tied up in language, according to Kandel–for example, whether the formal or familiar “you” is used matters in other languages, but there is no such distinction in English. Sometimes the difference is even more subtle: someone mentioned that Anne Frank’s diary was much “livelier” in Dutch than in English, but was unable to explain just quite how.

Other, non-translation-specific, changes can creep in. McHugh said that when the German rights for her novel China Mountain Zhang were sold, her agent wondered whether all the characters would sit down to a nourishing bowl of Brand Something soup. When McHugh asked what he was talking about, he explained that in Germany, they sell product placements in books, so the characters might all stop their conversation to sit down to a bowl of their equivalent of Campbell’s Soup, and then resume their discussion. (This apparently is the case in the German edition of Kim Stanley Robinson’s Pacific Edge.) Speaking of product placements, Gunnarsson thinks they are one reason that historical films aren’t as popular any more–you can’t sell product placements in them.

Sometimes a knowledge of other languages can affect the English original as well. McHugh said that since in Chinese everything is in the present tense, with a “tense marker” at the end of the sentence to say whether it is past, present, future, or what, she wrote China Mountain Zhang in the present to give it that feel. She also thought that, while science fiction may be partially global, it’s not yet Chinese. Many concepts which we assume are understood around the world–such as faster-than-light travel and time travel–are unknown outside of science fiction circles and perhaps not known even there.

Science fiction poses its own special pitfalls for the translator. A translator needs to know some science, otherwise you get something like “brown movements” for “Brownian motion.” But in Japan (and other countries, no doubt), translators are not educated in science, and scientists are not educated in languages. The result is that it is very difficult to find someone who can translate science fiction well. One thing Kobayashi said was that good style and characters are not important to Japanese science fiction readers (this is undoubtedly a result of the division of education as well), and that the literati hate science fiction. I suppose this makes translating a bit easier–one needn’t spend as much time searching for just the right phrase.

Someone of course noted that sometimes it may be necessary to translate English into American or vice versa. “He was left standing outside her door in his pants and vest” means one thing to an Englishman and another to an American.

The panelists agreed that the best translations are the ones you do yourself, but that it was impossible to learn that many languages and translate your work into them and still have time to write anything new. The translators on the panel said it took them about six months to translate the average novel. Kobayashi said Lucius Shepard’s Life During Wartime took him a year, due no doubt to Shepard’s heavy use of stylistic devices. A film novelization might take only one month.

While most translators don’t talk to the authors whose work they are translating, sometimes it can be very helpful, as when Joe Haldeman’s Japanese translator called up to ask just what he meant by “Unitarians on quaaludes.”

Kandel noted that in Italian there is a proverb: “To translate is to betray.” Ironically, the words in Italian for “translate” and “betray” are very similar (“tradurre” and “tradire”), forming a word-play that is entirely lost in English.

[Mike Glyer] Film Program: Assistant division chief John Sapienza readied six departments cross-country from his home in Maryland, including the film program. The film program department head, a fan from Sacramento, resigned at literally the last minute because of his father’s serious illness. Sapienza took over the department at the con. That’s when John discovered that the Sacramento fan, despite earlier assurances, had not obtained licensing for ConFrancisco to show tapes of the movies announced in the program.

As John Pomeranz tells the rest of the story, “[Sapienza] jumped in and spent the last day before the convention arranging the necessary legal permissions for as much of the program as he could. The miracle of it is that he largely succeeded. Although the program schedule bore no resemblance to the one printed in the pocket program, there was a varied and interesting program, and those who attended apparently enjoyed themselves. John is one of the great problem solvers of fandom, and he never gets enough credit for the excellent work he does because he is also one of the most self-effacing men I know.”

John Sapienza responded to this published conreport, “I’ll take all the egoboo that comes along. In the interest of fairness, however, I should point out that the people who actually created the film program on site were our superhero Richard Ney and his crew. I was a programming subdivision head with six departments to coordinate. Richard was both technical operations department head for the Programming Division, and my subdivision’s film operations department head. Over a four-day period, I scrambled to acquire licenses to show the films that were on the printed film program. I fed the licenses to Richard as I got them, and he and his fine film crew created each day’s film program and got it into the newsletter. In addition, they went out to rental stores and got us a lot of public domain films to fill out the empty spaces in the program. They all did a great job saving the film program; Richard Ney did a fine job coordinating that while running technical support for programming as well.”

John Sapienza illustrates my personal definition of heroism in the context of the Worldcon, someone taking responsibility to get the job done in spite of any difficulty. It’s most dramatic in a last-minute crisis, and there are even a few people who seem to prefer working in crisis because of the emotional payoff, but I saw no less magnificence in Gary Anderson’s solution to building the bridge simply because it was carefully planned, or in Elayne Pelz’ stepping in to run the Art Show simply because she started months before the con. ConFrancisco announced its own pantheon of superheroes and heroes at Closing Ceremonies. SuperHeroes of ConFrancisco were Doug Houseman, Richard Ney, Spike Parsons and Gail Sanders; on the roll of Heroes were Shawn Blanchette, Shelia Bostick, Robbie Cantor, Todd Dashoff, Kathryn Daugherty, Kerry Ellis, Cindy Fulton, Rob Himmelsbach, Jean Hortman, Richard Lawrence, Gary Louie, Ellie Miller, Kathy Nerat, Jerry Pournelle, Joey Shoji, Sharon Pierce, John Sapienza, Donya White, Dianne Wickes and Jacob Wright.

Tending to be overlooked on such lists, which are job-oriented, yet gratefully acknowledged by their co-workers, are people who sustain the spirits of those around them. T. R. Smith told me, “I’m contemplating enrolling in the Peggy Rae Pavlat School of Serenity and Politeness.” T. R. greatly admired Peggy Rae’s calming influence on everyone she worked with.

[Mike Glyer] Turning Klingonese: Klingon hall costumes were everywhere. Sam Pierce said there was even a Klingon highlight in the Art Show Auction: “Late in the auction, a small dragonish drawing came up for bid. After a young woman up front offered $25, a brash young fellow from the back said, ‘I refuse to be outbid by a woman who hums Barney tunes.’ The race was on and, in five dollar increments, we were soon up to $150. Brash spoke up again with some equally antagonistic comment. She replied with a string of Klingon that was obviously an oath of sufficient power to peel paint. The bidding continued to $225, when the fellow finally realized that he had so antagonized her that she’d have reached really deep to keep him from getting the piece. To our cries of ‘Wimp- !’ he conceded the drawing.”

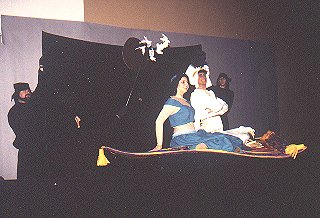

The masquerade boasted at least three Klingon entries, such as the award-winning “A ‘quiet’ Klingon Night at Home” performed to the tune of “The Masochism Tango.” Roy Pettis counted so many Klingon costumes and events at ConFrancisco he said, “I don’t think I have seen such a common costume theme since the summer after Star Wars when I went to Balticon and was overwhelmed by Princesses in white robes and rum-raisin-bun hair-styles.”

The Klingon Assault Group hosted several program items, but reportedly when they didn’t show up to run the “Klingon Dating Game” the standing-room-only audience spontaneously generated the program. Andrew Bustamante told me a volunteer moderator, in Federation dress, selected contestants from the audience who also wore appropriate hall costumes. Bustamante said questions included: “What is your idea of a perfect date?” “What is your favorite fetish?”

He continued, “A Bajoran woman had to pull her phaser on a Klingon contestant: ‘I hear Bajoran women are easy.’ ‘Try it and see what I light up!’ A demonstration of Klingon smash and grab carry-off techniques by the male volunteers was interrupted by a silverhaired blonde in a silver, skintight suit with cape who picked up a Klingon male as if he were a small child, threw him over her shoulder and marched out of the room with him looking very confused. After a few moments of the audience roaring, he tried to carry her back and almost made it to the stage with her.”

Masquerade:

[Mike Kennedy in The NASFA Shuttle, September 1993 issue] When I got there the line was already snaked around several times inside and wrapped one-third of the way around the big block. …Some people doubtless saw the line and decided not to go to the masquerade at all and some people were apparently turned away. …Uncle Timmy [Bolgeo], who was one of the last people they let in, found an empty seat right in the middle on the fourth row. I didn’t have to tell him he was slime since several people had beat me to it.

[Mike Glyer] The crowd was admitted slowly, at first, because the slick marble floor in the Esplanade lobby posed a safety hazard. The line quite outnumbered the Esplanade Ballroom’s 2,914 seats, so even more time was also devoted to finding and filling individual empty seats. The fire marshal permitted no standing room: no one could be allowed in unless they’d have a seat.

Though starting time was announced for 8:00 p.m., the first costume came onstage at 8:55 p.m. Janet Wilson Anderson, Mistress of Grand Guignol, that is to say division chief overseeing the Masquerade, defended: “Why did the Masquerade start late? Don’t blame the costumers or the crew. They were ready at 7:30 p.m. I had the judges backstage, had loaded in the limited mobility and vision folks and was standing at the main doors ready to open them when the Floor Manager stopped me. He advised me of a potential safety problem. It took 28 minutes to resolve. As soon as the problem was cleared up, I opened the doors – at 7:58. Load-in took 52 minutes longer than anticipated, mostly due to the worry over a mad rush on that slippery atrium floor. I’d had a couple of incidents with the floor already during the day, so we elected to slow people down.”

The Mistress of Grand Guignol commented more than once on the priority given to safety, begging the question of why, after her crew had been sliding around the Esplanade lobby floor all afternoon (“I’d had a couple of incidents with the floor already”) no one but the Floor Manager thought anything should be done about it. And why didn’t the Floor Manager deal with it before 7:30 p.m., when there was still time to inquire about floor covering (runners)?

“The remainder of the delay,” continued Wilson Anderson, “came from people refusing to relinquish the seats they’d saved for their friends over half an hour after putative start time. Guess I could have told the ‘ushers’ to be nasty about it, but it seemed impolitic to do so.”

Despite rumors, Kent Bloom was sure, “We didn’t turn away 1000 from the Masquerade. The ushers and line monitors I talked to said that they turned away 100 or so, and that no one who arrived before 8 p.m. (the scheduled starting time) was turned away. It always hurts to turn anyone away. We’ll try to do better next year.”

The start of the Masquerade loosed a completely unexpected problem, wonky stage lighting software. Mike Kennedy reported, “The Moscone’s computer, starting at about the intermission between entries 25 and 26, kept cycling on the lights in a ‘fail-safe’ mode. As things went along, the crew got faster and faster in shutting them back off so that it became a nuisance rather than disruptive. Gary Anderson said the tech crews “Virtually [had to] tell the Moscone building engineer what to do about it, actively stand with a tech’s finger on the switch to reset the lights when they went wild, and spend what were supposed to be off-hours the next day checking out the software reload.” Upon investigation, said Anderson, “We found out that there had been bugs all through the system, and that it had just been reloaded (but not thoroughly tested) before our arrival.”

Overcoming all problems, the ConFrancisco Masquerade offered 50 entries (12 Masters, 18 Journeyman, 20 Novices), consisting of 37 Original entries and 13 Recreations, totalling 115 participants on stage. [See dozens of ConFrancisco masquerade entry photos at Fanac.org: ConFrancisco – 1993 WorldCon – Year Index – Part 5.]

[Mike Glyer] Parting Shot: Janet Wilson Anderson’s feels, “I have relatively little patience for those who grouse that they had to wait a bit, when literally hundreds of folks have put in such incredible effort to provide them with a show that can be seen in no. other venue.”

[Mike Glyer] Site Selection: As co-chair of the LA in ’96 bid I spent most of my time over the weekend either arranging parties or taking votes and money at the Site Selection table. It surprises me to have this much material for a Worldcon report.

While others attended the masquerade on Saturday night, I counted votes with convention officials Kevin Standlee and George Brickner. Los Angeles was the only bid, so the winner was never in doubt, just the numbers. Los Angeles received 1,132 of the 1,286 votes cast.

[Mike Glyer] The History of ConFrancisco: Kevin told stories as we counted. He gave us the entire history of ConFrancisco, including the odd twists of fate that cost them the Marriott, a very large hotel just across the street from the Moscone originally intended to be ConFrancisco’s headquarters.

Just before the San Francisco bid won, in 1990, Ford Motor Company booked the Marriott for midweek dates that ruled out using it for the Worldcon. The committee scrambled to book more space in the Moscone and pick a new headquarters. Standlee says that after shouldering ConFrancisco out of the picture, Ford jilted the Marriott by moving its event to San Diego, but the Marriott never came back looking for ConFrancisco’s business.

ConFrancisco returned the favor by leaving the hotel, a rather sizable landmark, entirely off the street map in The Quick Reference Guide. Rumors also persisted that the hotel had no business other than 75 rooms taken by fans, but Mike Resnick, who stayed there, denied that it was any kind of ghost town: “At the last minute they booked an Esso convention; they were totally sold out on Saturday night, I know that.”

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

“carburetors that allow 90 miles per gallon” – I got a sense of how old this legend is when I saw a reference to it in Heinlein’s 1940 story “Let There Be Light”

Dave Clark said that he felt it was important for the chair to not try to do the staff’s job for them. He wanted to have a special project that was something only the chair could do, and that wouldn’t be a problem if it fell through. Bringing back the former San Francisco Worldcon chairs was his idea for his special project, and it was a splendid success.

One of the consequences is that Bill Donaho resumed publication of Habakkuk after a 25 year gap, and it was excellent. After ConFrancisco, Bill was a regular at Bay Area conventions and fan gatherings, until he passed away. This is an example of the unexpected good things that can happen because there was a Worldcon.

And at the time, I was in the Terrean, and we resolved (for the time being) a fan feud in the APA (the Treaty of SF).