Review by Michaele Jordan: We’ll start with the credits, as all movies do (although the credits in this movie were so tiny, I could barely read them on a good-sized TV set). 3,000 Years of Longing was directed by George Miller, who also wrote the screenplay, together with Augusta Gore. They based it on “The Djinn in the Nightingale’s Eye” by A. S. Byatt. It premiered at the 75th Cannes Film Festival on May 20, 2022, where it received a six-minute standing ovation. What? You’ve never heard of a movie getting a standing ovation? Neither had I.

It starts with Alithea (Tilda Swinton) on her way to a conference in Istanbul, saying she’s happy. Even when she is accosted – twice – by persons who might be more supernatural emissaries than strictly human, she’s happy. After all, she’s independent – both emotionally and financially – and engaged in work she loves, the study of stories. Although she is usually quick to pick up on such details, she does not notice that she is, herself, launching into a classic fairy tale.

Visiting a curio shop she finds a bottle. It’s a pretty thing with blue stripes curling up around the sides. It looks like a bud vase, except for the stopper. We know it’s important, because the film zeroes in on it so intently, but it looks nothing at like the traditional brass lamp from the fairy tales. Perhaps it’s a red herring?

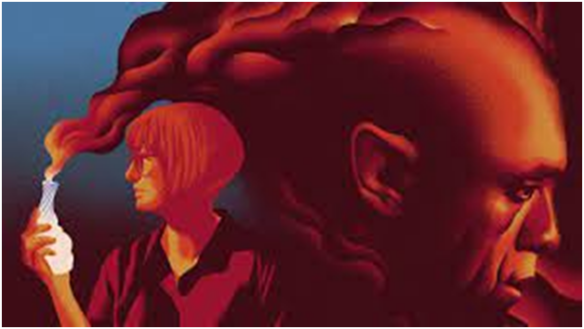

But, no, it’s THE bottle, as Alithea learns when she tries to wash it. Enormous plumes of black and red smoke snake around the bathroom. We know it’s the djinn, of course, but he’s so large that only small parts of him are visible in any given frame. It’s some while before we are able to confirm that the part is, as advertised, played by Idris Elba. (He gets smaller later on. As he says, “I try to fit in.”) [Beware spoilers from here on.]

He makes her the usual offer – three wishes – followed by the usual conditons – don’t wish for more wishes, etc. – but with one extra condition: the wish must be your heart’s desire. And there’s the rub. She doesn’t have a heart’s desire. She’s already happy. This dismays him hugely; he begs her to reconsider. Surely everybody wants something. But she can’t think of a thing, and she doesn’t understand whey he’s so upset. Why doesn’t he just go back to Djinn land and let her get on with her storytelling studies?

But he can’t. He needs her to want something. He can’t be free until she makes her wishes. He’s been imprisoned for 3,000 years, and is still waiting to grant somebody three wishes.

He started out a free djinn, visiting his half-djinn cousin the queen of Sheba, when Solomon came calling. Solomon did not like having a third wheel around. He stuck him in a brass lamp and told a bird to fling the lamp into the Red Sea.

He stayed in the sea a long time. He has, in fact, spent a lot more time in his lamp than out in the world. Eventually the lamp washed ashore, and was found by a palace concubine. She hid the magic lamp under a flagstone for safe keeping, and wished for love, which turned out be a bad idea. Her second wish was an even worse idea. When the palace politics got bloody, the djinn begged her to use her third wish to save herself. But she was too busy screaming. So then she was dead and in the absence of a third wish the djinn was back in the lamp.

He wanders (invisibly) around the palace for a century, trying to nudge several generations into looking under that flagstone. He is almost discovered by a little boy who grows up to become Sultan Murad IV. (In case you are a little weak on the details of 17th century Middle Eastern politics, Murad was a genuine historic personage, and not – so far as we remember today – unlike his portrayal here.) Little Murad was easily distracted by booze and bloodshed.

His kid brother Ibrahim also grew up to become sultan, and a remarkably bad one, at that. His main interest in life was the acquisition of fat concubines, and a variety of sexual stimulants necessary for maintaining the lifestyle. Ibrahim did not find the lamp under the flagstone, but Sugar Lump, one of his favorites, did. Unfortunately, she was so terrified by the giant and the smoke and all that she wished him back in his bottle at the bottom of the sea.

Two hundred years crawl by before the Djinn comes into the possession of Zefir, the bored, lonely third wife of a merchant. Her first wish – and it is truly her heart’s desire – is for knowledge. Her second wish is for more knowledge.The Djinn is charmed, and falls in love. He showers her with books, and helps her build scientic apparatus. He encourages her to put off that third wish, so he can linger. He shows her things that normally only djinn can see.

But the more she learns, the more trapped she feels in her tiny world. She starts to resent him, even to blame him – as if, because he showed her the problem, he caused it. In a desperate attempt to reassure her, he creates a lovely little bottle (we’ve been wondering how he got from the lamp to the bottle) and retreats into it to prove he is not controlling her, to show her that she is in control of him. It works too well. She wishes she could forget she ever met him.

You must be wondering if I’m going to tell you the whole plot, committing spoiler after spoiler along the way. But I haven’t actually told you anything. Just what you already knew from the beginning: that there’s a djinn in the bottle, that djinns grant wishes, and that wishes are invariably dangerous. I promise these stories will still be fresh for you when you see them.

The movie is not about these intervening stories. They are just there because that’s how fairy tales always go. The movie is about how Alithea and the Djinn come together over these stories, about how stories bind humans (or even non-humans) together, and about how we must build on the stories we already know tbefore we can reach for anything new. The movie is about how we wish and what we wish for, and why so often that doesn’t work.

It’s also about how we take in more with our eyes than we can tell in any story. The visuals in this movie are amazing. (I meant to dazzle you with photos, but there are surprising few publicity stills out there available for common use.) It’s not gorgeous because of special effects, although there are those, but because of the focus on how much beauty is already out there, and how little it changes our minds. There’s a lot of action within the intervening tales, but the action doesn’t change anything either. But there is a new twist to the ending – not a change, just a different reflection on the unchanging bedrock of fairy tales. I found this movie to be very close to perfect.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

The credits were tiny – even on “a good-sized TV set” because they were designed to be seen on a far more good-sized movie screen. And standing ovations for movies happen often at situations like the Cannes Film Festival, where she talks about this ovation occurring, because the producers, directors, writers, and stars are frequently present.

While I didn’t see 3,000 Years of Longing at the Cannes Festival, I’ve seen it and it’s quite good. I enjoyed it, too. Though I didn’t give it a standing ovation.

From what I read about the latest Cannes Film Festival it sounds like everything gets a standing ovation — but when the ovation for one new film lasted “only” four minutes the critic wondered if it was in trouble…

Yo! The movie took me through a lot of my own emotions, too…the right questions asked, the right amount of time to think through them…

Well, now you know. I don’t actually watch Award Shows — not even the Cannes Film festival