By RL Thornton:

Introduction: When we think about speculative fiction (i.e. science fiction and fantasy), we usually think about novels, movies, or TV. But there are authors and musicians who try to expand those visions into sound. Ursula K. Le Guin was one of those people. This week, we will look at two of Le Guin’s musical collaborations with Todd Barton (“Kesh”) and David Bedford (“Rigel 9”), and next week, we will discuss Le Guin’s collaborations with composer and music educator Elinor Armen.

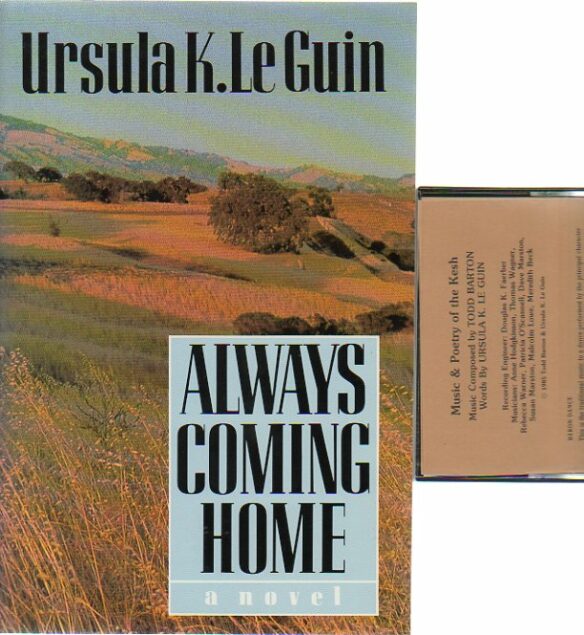

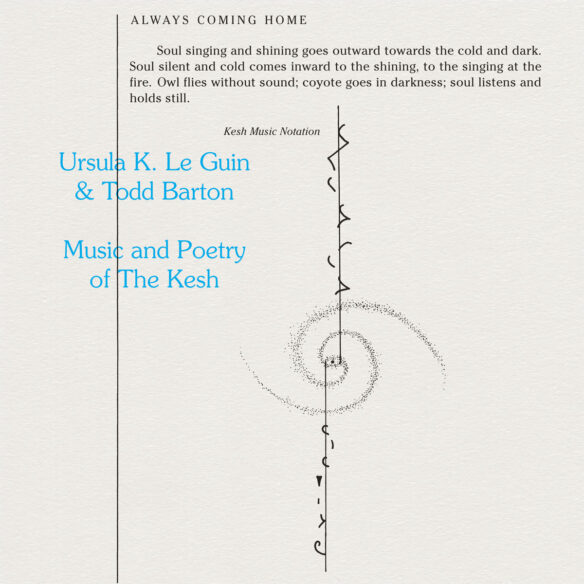

“Kesh” and Always Coming Home: Originally, this collection was on a cassette that came with a deluxe first edition of Le Guin’s 1985 novel Always Coming Home. Le Guin teamed up with synthesist Todd Barton to create a soundtrack to her 1985 novel Always Coming Home.

But it was reissued by the label RVNG International to acclaim by periodicals Pitchfork, who deemed it a Best New Reissue that “highlights the rich, totally immersive art Ursula K. Le Guin sought to create” and UK’s Guardian, who called it “deeply weird and enjoyable” even though they mistakenly called it an “electronica” album”. The first edition of 1000 vinyl LPs sold out and it was reissued a second time in 2018.

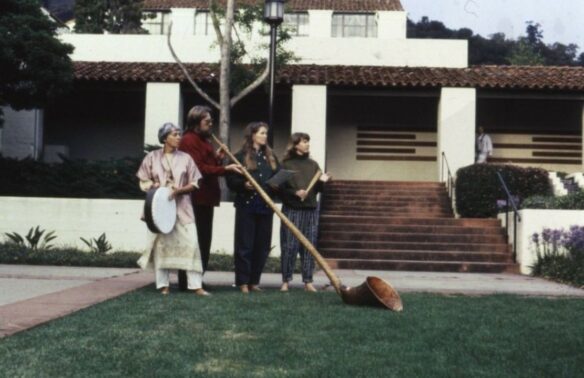

Music And Poetry of the Kesh is definitely different. Much of it is grounded in woodland sounds and the majority of the tunes feature sparse solo and duo unaccompanied singing that occasionally plays against a drum beating out time. Those unaccompanied tracks seem immediate and recorded live but feel a little thin due to the lack of reverb. Most of them seem to be a little thin sonically, though Barton occasionally brings in his synths (“Heron Dance”) and uses multitracked voices for “Long Singing.” It is said that there are instruments designed for the album but I didn’t really hear anything new–there was one sound that resembled a didgeridoo in “A River Song,” possibly the long droning horn that I read about.

Previously, I rejected this album out of hand because it lacked sound production values, but this album didn’t make sense to me until I actually started listening to it and reading Always Coming Home at the same time. As Le Guin’s prose cast its spell over me as usual, the soundtrack actually made Le Guin’s novel come alive. The decision to make the tracks part of the local soundscape suddenly made sense. It felt like I was among the Kesh! I swear it was absolutely magic. Who knew that the choice to use a minimum amount of recording tech would work so well! I’m really impressed. If you are a fan of Le Guin and especially a fan of Always Coming Home, I would say this is a must buy.

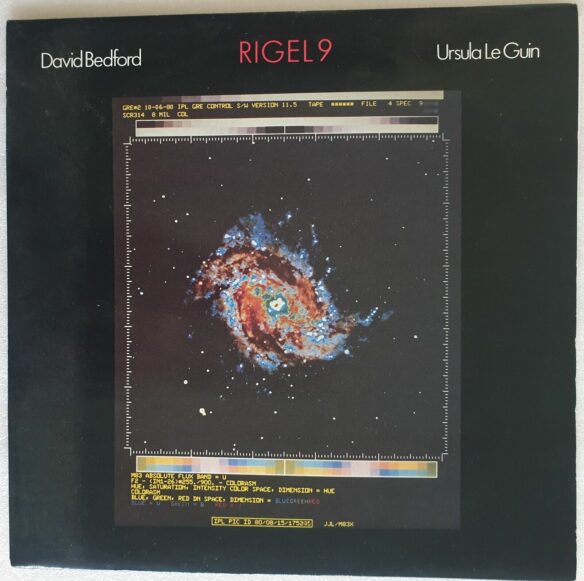

“Rigel 9” and Bedford: Next, we have Le Guin creating a libretto for a literal “space opera” with composer David Bedford and the County of Avon Symphonic Wind Band. In this story, explorers from Earth land on Rigel 9, a planet that seems to be nothing but bizarre trees. When the party begins to explore the world, everything changes after one of them is kidnapped by intelligent life. Bedford’s songs are grounded in that jazzy 70s British prog rock sound reminiscent of bands like Gong, Soft Machine, Robert Wyatt, and Henry Cow. Occasionally, I hear a brass band playing but most of the time it’s buried in the mix.

When the songs end and the spoken part of the libretto begins, Bereford’s blaring synths lay down weird background songs that are, well, like the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s soundtracks for Doctor Who. Mix in the Dalek-ish robotic vocals that instruct the ship’s explorers, and Rigel 9 feels a lot like a rogue Doctor Who episode. My guess is the Bedford was trying to sell his rather unusual concept by deliberately pandering to the Whovians. Unfortunately, adopting the Whovian soundworld dilutes the work’s originality. The best part of Bedford’s musical setting is his cunning choice of ethereal female vocals to serve as the voices of Rigel 9’s inhabitants–literally unearthly and beautiful.

So what about Le Guin’s libretto? Honestly, it’s really meh for her and possibly the least interesting work that she has ever done, but even the least Le Guin is better than most. The explorer’s conversations are pretty flat and the characterizations are also flat, but the plot twist is actually pretty neat. Since this is on Apple Music and probably Spotify, I would suggest listening to Rigel 9 on those services before buying. And Whovians might want to try it too.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

The unusual, long horn in the picture is probably an alpenhorn.

It might have been modified to have a larger bell.

Alpenhorns really are eight feet long or much longer. Their sound carries a long, long way through the alps.

Thank you so much for turning me on to these records. I’m listening to the Bedford as I write this week’s edition of Telegraphs & Tar Pits for APA-L. It’s wonderful!

Did Le Guin consider Always Coming Home a novel? I seem to remember her talking about it as an ethnographic work of the future.

It always seems to me that me that it is a set of narratives, which I think lacks the unifying story that a novel has. Don’t get me wrong — it’s an extraordinary work, just not what I think of as a novel.

One ought not to discuss Le Guin’s engagement with music without at least a mention of Uses of Music in Uttermost Parts, a suite of muisical pieces for which she wrote the words and Elinor Armer the music. Le Guin also provided the spoken-word vocals for about half the pieces on the album where it was first released, excepting the first piece (“The Great Instrument of the Geggerets”), where Leguin and Armer share the spoken vocals.

Dan’l: That’s what Part II will be about.

Apple Music has Songs and Poetry of the Kesh, I just discovered.

https://music.apple.com/us/album/music-and-poetry-of-the-kesh/1336658683

Also available on Bandcamp, which is where I got my copy:

https://ursulakleguintoddbarton.bandcamp.com/album/music-and-poetry-of-the-kesh