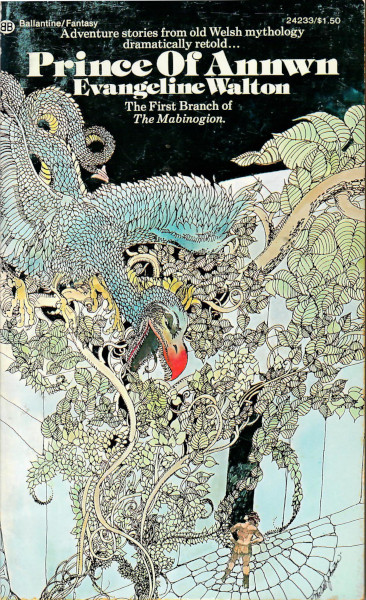

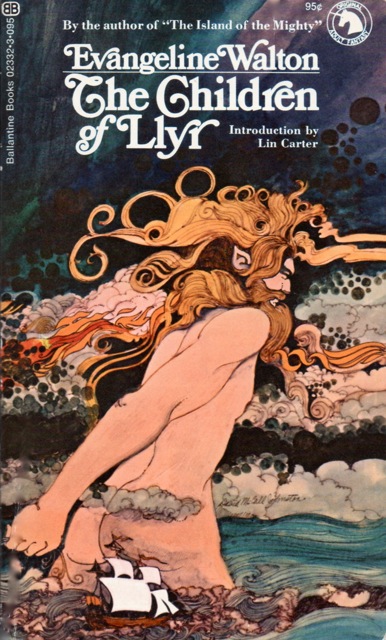

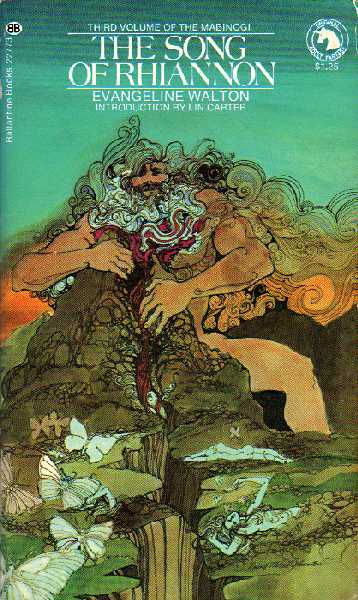

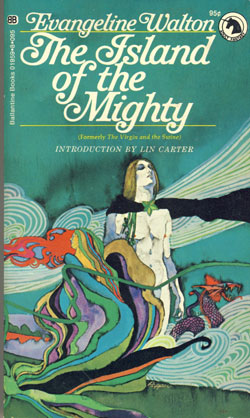

Covers of the Ballantine Books paperback editions from the 1970s.

By RL Thornton.

Returning to Literary Fantasy. Throughout the history of speculative fiction (i.e. SF/F), the genre has always had a problematic relationship with the literary mainstream. Aspersions were initially cast by pulp/”scientifiction” types on literary values and even as those values crept into the genre via writers like Heinlein and the New Wave, the term “literary” has been a bad word for readers who want their prose to go down easy.

As a result, the term “literary fantasy” has always been suspect, because the very idea of literary gatekeepers is always bound to offend genre advocates. This is unfortunate, because the values celebrated by literary fantasy should be most acceptable to anyone who cares about speculative fiction. Very high-quality prose (most important of all), difficult structures, and deftly realized characters and plots–it all sounds great to me!

And as we go back to literary fantasy, we should be looking to quality gatekeepers like the Mythopoeic Society and the World Fantasy Convention, who have been part of literary fantasy all along. We should be looking to literary fantasy, which points us to authors who stretch the boundaries of speculative fiction, regardless of their popular appeal (i.e. Neil Gaiman).

So we come to Evangeline Walton, who was given a Lifetime Achievement Award by the World Fantasy Convention and won multiple awards from the Mythopoeic Society for novels in her Mabinogion tetralogy. These novels are a retelling of the Mabinogion, a medieval collection of eleven prose stories based on medieval Welsh manuscripts.

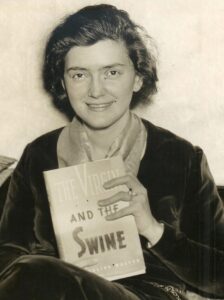

Evangeline Walton’s Story. If you look at the history of fantasy literature, Walton (originally known as Evangeline Wilna Ensley) plays a unique role in the tale. According to Wikipedia, she wrote most of the tetralogy from the 1920s through the 1940s and continued reworking them despite the poor response from the first book (initially titled The Virgin And The Swine, eventually republished as The Island Of The Mighty). Walton also completed a Theseus trilogy and only one of those books have been published. While Witch House (1945) and The Sword Is Forged (1983) were published, there are also other unpublished novels. Stevie Nicks (of all people) has the film rights to the Mabinogion tetralogy.

Walton was a pre-Tolkien fantasist, who was properly rediscovered when the legendary Ballentine Adult Fantasy collection of pre-Tolkien fantasy was assembled. Eventually all four novels were published (Prince of Annwn, Children of Llyr, Song of Rhiannon, and The Island of the Mighty in proper order). As the Mythopoeic Society and the World Fantasy Convention probably realized, these books are marvels of prose style and characterization that infuses her knowing individual characterizations and the myths of Wales with the lyrical promise of Lord Dunsany and his incipient feel for cosmic horror.

Here is an example of Walton’s beautiful prose from the very beginning of Prince of Annwn:

THAT DAY Pwyll, Prince of Dyved, who thought he was going out to hunt, was in reality going out to be hunted, and by no beast or man of earth.

The night before he had slept at Llyn Diarwya, that lay halfway between royal Arberth, his chief seat, and the deep woods of Glen Cuch. And at moonset, in the last thick darkness before dawn, he woke there.

He woke suddenly, as if a bell had been rung in his ear. Startled, he peered round him, but saw only sight-swallowing blackness that soon thinned to a darkness full of things yet darker. Of half-shaped, constantly reshaping somethings such as always haunt the lightless depths of night, and make it seem mysterious and terrible. He saw nothing that meant anything, and if he had heard anything he did not hear it again.

The Tetralogy’s Story. In these books, the characters of the Mabinogion use their skills and druidic skills to struggle with the menace of merciless gods, the dangers of other supernatural mysteries, the perils inflicted on them by rival druids, and their own impending fates. Most notable of them is Math (son of Mathowny), who presides over all of them with the foreknowledge of the others’ immediate future and the Future To Come. The quote from Wikipedia is apt: “My own method has always been to try to put flesh and blood on the bones of the original myth; I almost never contradict sources, I only add and interpret.”

Some of the other themes are the evolution of Wales culture as seem through the lens of the “Old Tribes” and the “New Tribes,” including explorations of what powers druids have, how changes in culture and the influence of Christianity changed the relationships between men and women, and the inevitable changes that would lead to today’s world.

All of these themes are carefully interwoven into a potent braid that carries you along through each novel into an ending which ends with an ellipsis and carries Wales into the uncertain future.

The Stories Themelves. The Prince of Annwn: Pwyll, the Prince of Dyved, encounters Death (the god Annwn) who challenges him to take on tasks that the god cannot achieve on his own.

The Children of Llyr: The terrible fates of the five children of Llyr (with a focus on Bran The Mighty and his sister Branwen) are told. The Cauldron, which is best known in Lloyd Alexander’s Prydain novels, plays a key role in the telling.

The Song Of Rhiannon: Relates the grim adventures of the Prince of Pryderi and the remaining member of the Llyr children, who actually gets some happiness for once.

The Island of The Mighty: The tale of Gwydion (not necessarily the one in Alexander’s Prydain), nephew of the great and powerful Math, and the troubles that he encounters due to Gwydion’s own trickery and his own fate.

Difficulties You Might Encounter. Despite the tremendous power of Walton’s prose, current readers might have problems that come with the setting of the Mabinogion’s stories and the times in which Walton started writing those stories. Primarily, the ghost of heternormativity hovers over all these novels due to the medieval origin of the stories, and the current world of queer literature only briefly appears in close relationships between male blood relatives.

But this flaw is mostly nullified given the historic nature of the tales. If we believe in cultural relativity, certainly it should apply to the past as well as today. So with a little bit of grace, the virtues of Walton’s story-telling overshadow the problems.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Another thing for which Lin Carter cannot be given enough credit is rescuing Island of the Mighty from obscurity and then getting the subsequent three volumes into print for the first time as part of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series (as pictured above).

These have been sitting on my shelves for a long time. This year I need to read them. Thanks for the lovely reminder.

I loved this tetralogy and was fortunate enough to get the four paperbacks signed by Walton at the World Fantasy Convention in 1983.

I read the reissues and didn’t even realize they were reissues! I thought Walton was another ’70s writer. Anyway, good books, and a relief from the great Morte d’Arthur Overstock of the 1970s. (I love the Arthurian legend. A lot. But there were too many retellings, many that didn’t add anything of their own.)

I read these back in the ’70s and have always been grateful that I encountered them before studying the medieval originals (and after encountering Lloyd Alexander’s versions). Because each is delightful in its own way, but by reading them in the order Alexander > Walton > original I was saved from cringing at how completely the original matter was transformed. (That is, Walton is more true to the original, but still takes many liberties, and Alexander’s series is only loosely connected with the Mabinogi.)

I was delighted to meet Walton in person at a small convention (I think maybe it was a Mythcon?) and was able to tell her how much I loved her work.

One of my party tricks is being able to recite the opening scene of Pwyll from memory in the original medieval Welsh.

@Heather: And a fine trick it is!

I too thought the 70s reprints were first-time printings.

Not at all surprised the woman who sang “Rhiannon” and calls her publishing firm “Welsh Witch” has the rights to these. Do something, Stevie!

I read these as they came out, eagerly awaiting the next. They’re not exactly druids – they (may be) pre-Roman invasion. The review also makes it pretty grim, when it’s not. It is, however, not easy.

As much as I enjoy Lloyd Alexander, that’s not the Mabinogion, just based on it, whereas Walton is retelling the Mabinogion in modern language.

And yes, as I raise my eyes to my hutch above my computer, I see my copy of The Mabinogion, so I do, in fact, know what I’m talking about. (And I can pronounce Cymraeg coerrectly, as corrected by my late mother-in-law, a Welsh war bride.)

I have this set (somewhere in a box) as well as in e-book. And I have Guest’s translation. (That long long list of characters, in the one tale, where some fo them I think I’ve heard of elsewhere – clearly hooks for hanging more stories on!)