By James H. Burns: Americans have never needed a guidebook for courage. And the men who served in World War II were amongst the bravest citizens our nation has ever produced.

By James H. Burns: Americans have never needed a guidebook for courage. And the men who served in World War II were amongst the bravest citizens our nation has ever produced.

Yet, one of the biggest influences on that generation has remained generally uncommented on. Decades later, it can almost be viewed as a secret text, or a vast compendium, that may well have helped prepare our country’s youth for the immense challenges that awaited them.

In the 1930s, during the height of the Great Depression–still the toughest economic calamity that ever faced the United States–ANYONE could tune in, on the radio, to the terrific adventure series, comedies and dramas that were performed LIVE, for national broadcast.

It didn’t matter if you were rich or poor, or what race or creed you encompassed. There was a wide array of delights simply waiting to be discovered.

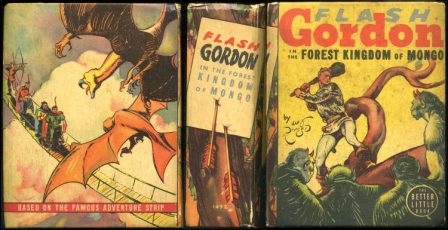

Many youngsters, whether in the most rural climes or the toughest streets of our cities, took particular delight every day in the fictional exploits of such action heroes–and “do-gooders”–as Jack Armstrong (“The All American Boy”), Gangbusters, and The Lone Ranger. (Other series, including Dick Tracy, Flash Gordon, and Jungle Jim, were based on popular newspaper comic strips.)

It was truly a meritocracy of joy — everybody, potentially, could join in on the fun.

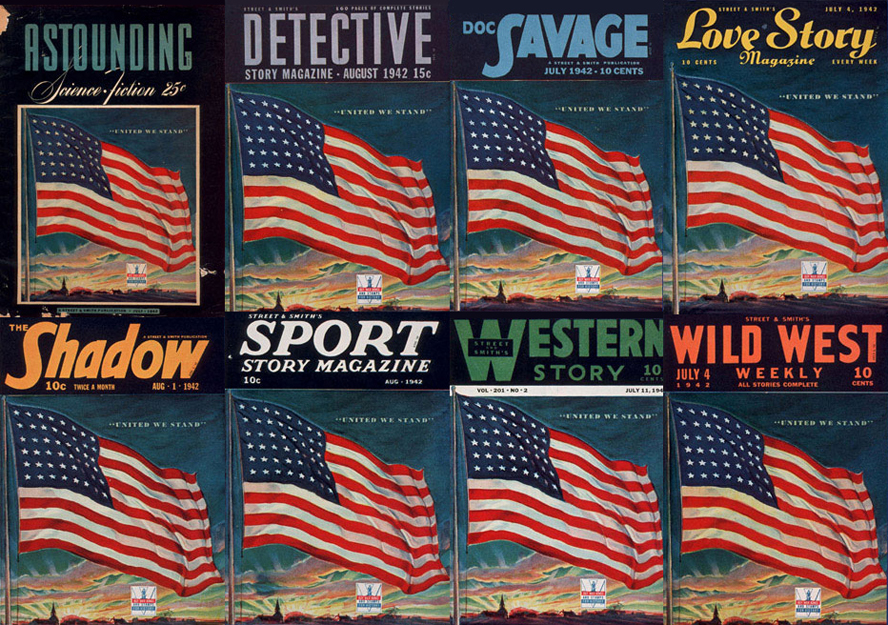

On the newsstands in the 1930s was another miracle of the imagination: pulp magazines. The roughly 10-by-7 inch magazines featured novel-length tales, or collections of short stories, in virtually every category of prose. But it was the adventure stories that again caught the attention of many kids.

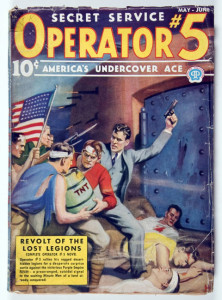

The most popular heroes, always named in the titles of their periodicals, were highlighted by Operator No. 5 (a secret service agent); Doc Savage ( a superb athlete AND genius who spanned the globe thwarting “evil masterminds,” and whom many credit as a key influence on the comics’ Superman); G-8 And His Battle Aces ( World War I air force pilots); and the crimefighters The Spider and The Shadow (the latter inspired by a successful radio series).

(These were magical monickers for a legion of our neighbors from coast to coast, in a time when more people seemed to take the time to read actual STORIES…)

(These were magical monickers for a legion of our neighbors from coast to coast, in a time when more people seemed to take the time to read actual STORIES…)

Youngsters across the United States thrilled to this newest roster of exciting archetypes (often passing their magazines onto friends, widely increasing the publications’ already impressive circulation).

(No doubt, the radio shows had helped whet the country’s appetite for derring-do!)

For kids like my father, Hyman Birnbaum (later “Hugh Burns”), there was another phenomenon of fascination:

The science fiction pulps.

My Dad was as poor as a kid could be during the Depression, raised on the lower East Side of Manhattan, and in Brownsville, Brooklyn. (It was a period, my Dad remembered, when even the most devoted of fathers struggling to find a job could find himself on a bread line, trying to bring SOMETHING home for his family’s supper…)

But along with other teens, and men in their twenties, my father could be transported to the farthest reaches of the universe, or to the cusp of the development of a spectacular new scientific innovation.

(Having been weaned on Flash Gordon — in the comic strips, “Big Little Book” adaptations, and in the film serials starting Buster Crabbe!–my Dad’s favorites were Thrilling Wonder, Planet Stories, and Astounding.)

Born in 1924 (like many other World War II vets), my Dad was exactly the right age for this burgeoning of what was also called “extrapolative fiction”. (By 1939, many of science fiction’s soon to be legendary writers were making their professional debuts, including Robert A. Heinlein, Stanley G. Weinbaum, and Isaac Asimov…)

Just a few years later, my Dad was there marching with Patton’s troops, a decorated army infantryman, who also saw battle in the Hurtgen Forest, and the Ardennes.

(Ultimately, my father, like many other early science fiction fans, was drawn to a career in technology, becoming a mechanical engineer, and teaching at NYU, and for decades at CCNY, in Harlem.)

There can be no debate that my Dad, and all of his brethren in uniform, would have proved magnificent no matter what they read, or what radio shows and movies they enjoyed. But it seems likely that “the hero pulps” helped pave at least some of their paths to perceiving the merits of valor, and the benefits of serving a higher cause, to vanquish those who would both massacre liberty, and the people who embrace justice and freedom.

(I am certain that my Dad thought more than once of Flash Gordon and his exploits on the planet Mongo (pit against the treacherous “Ming the Merciless”), as he heard gunfire aimed in his direction.)

In fact, my father was still stationed in Europe, when American forces dropped the atom bomb on Hiroshima. He said that it was as though the future had suddenly come to life, despite the devastation–

A concept that had existed only in the pages of a magazine, now an everyday reality.

Thanks to all our fathers–and mothers!–who strove so well in the military, we’ve had the opportunity to flourish in the greatest Democracy the world has ever known–

In what was once simply–and with gallant foresight–a happy dream of tomorrow.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

You are older than me but my grandfather grew up in the period of your father. He’s the one that got me into science fiction. I still remember him taking me to ET. Its actually the strongest memory I have of him.

Science fiction in my grandfathers era was filled with an optimism that is so lacking in today’s fiction with its insistence on anti-heroes over heroes. Despite serving in the military and the trauma of the post WW-II years culminating in the 60’s he was a man that hoped in a better world (with and laser guns). Unfortunately the following generation threw the temper tantrum of temper tantrums and for a long while a sense of hope and wonder outside of rarities (like Jim Henson) was lost.

Was it so different? We have Han Solo, Batman, Captain Kirk, 007, that Clint Eastwood gunslinger, Hornblower, Shrek… Sure, our heroes aren’t as simplistic — they aren’t 98% courage and 2% cardboard like in days of old. They have doubts, bad tempers and ear wax. Is that so bad? Moreover, some of the old school heroes are still with us.

Thank you. That’s possibly the best thing I have read on this site. Curiously, it was those early American pulps that led to my own fascination with sf -via my mother. Some American servicemen setting up equipment for the Naval guns on Robben Island left a bunch of them behind. And a bored Sergeant manning those guns – my mum, found them, read them and was hooked from then on – very unusual for a woman back then, in that country. And yes, she was far more idealistic than I am. This may have had some effect.

My parents used to to swap what was effectively soft-core books with a neighbor. One summer when I ran out of books to read, I scanned a stack to see if there was anything I could stand, and that’s when I found a copy of The Skylark of Space. I read it, found out there were sequels to be had, and my dad looked at it, and said he remembered it from when he was a kid. This was the same guy who when he saw I was reading The Foundation said “oh, Asimov! I know him!” Turns out he used my dad’s book bindery three times a year. So I was bound to be a fan.

Nice article, thanks for the insight and some memories of my own youth – finding a stack of 1951 Astounding Science Fiction digests and getting hooked,

Ah, another triggered memory. I read my way through all of the school libraries I ever had access to, and I found among the stacks upstairs at Wayland High School’s library in Wayland Mass that they were subscribing to Analog! They never had the current issues out, so imagine my surprise in 1969 that they had issues back to 1964, including the failed experiment of ‘bedsheet’ sized magazines for some 2 years. The first big issue I ever saw was the yellow Sandworm cover that Schoenherr did for Dune. I was in love.

I talked to staff, and found that they kept no magazines longer then two years, which didn’t explain why they had a five year old SF magazine. I asked if I could take the older magazines they would be throwing out any day now, and Mrs. Williams said I could. By 1976, I owned a copy of every issue of Astounding back to the late 1940’s, and now I haven’t so much as looked at them in 15 years or more.