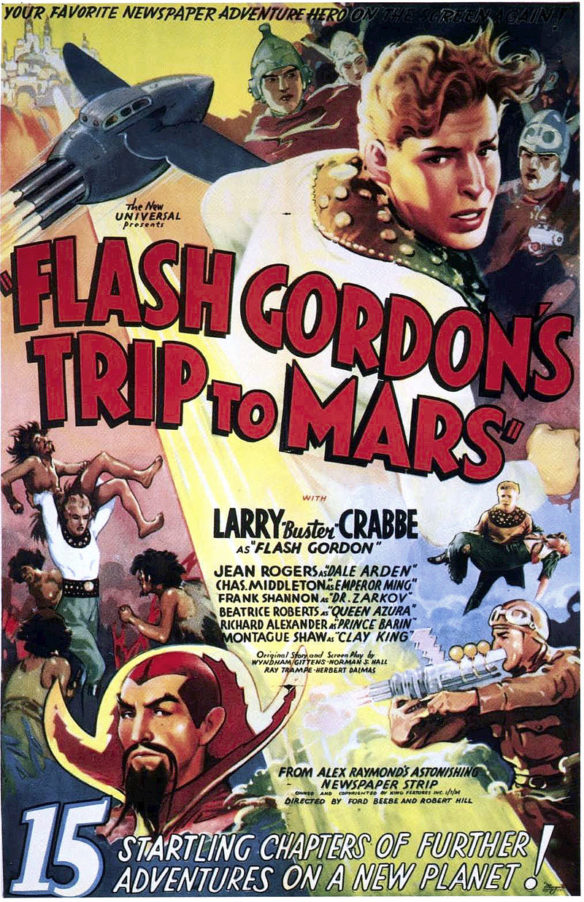

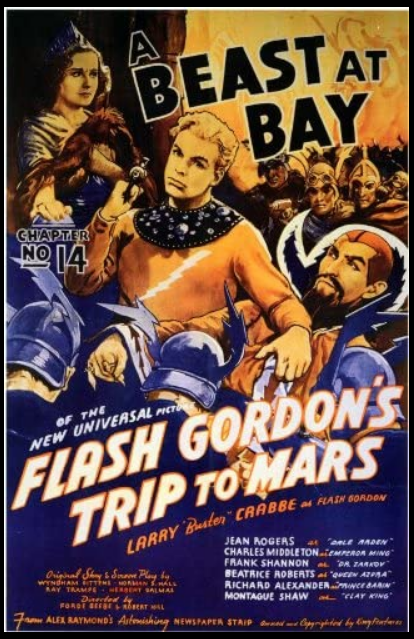

By Lee Weinstein: Atmospheric disturbances are creating worldwide turmoil. Buildings collapse as hurricanes and floods rage, while scientists heatedly argue about the cause. No, I’m not referring to the current effects of climate change. These are the disasters visited on earth by Ming the Merciless in the 1938 movie serial Flash Gordon’s Trip to Mars.

The second film in Universal’s trilogy of Flash Gordon serials, it is the longest, at 15 chapters, and a favorite of many. It’s the only one to contain magic mixed in with the science fiction and the only one not set on the planet Mongo. Some critics have preferred this 1938 sequel to the 1936 serial, noting its futuristic look, more coherent story structure, and the more proactive role Flash and his allies take against their enemies.

The original Flash Gordon comic strip was inspired by the Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Barsoomian novels, with Flash standing in for John Carter, as is evidenced by Flash’s physical prowess in various fight scenes. This was reflected in the 1936 serial where he is forced repeatedly to fight for his life, often with swords, against soldiers, ape-men and monsters. But in the 1938 Mars serial, Flash is more dependent on ray guns and cunning than on brawn.

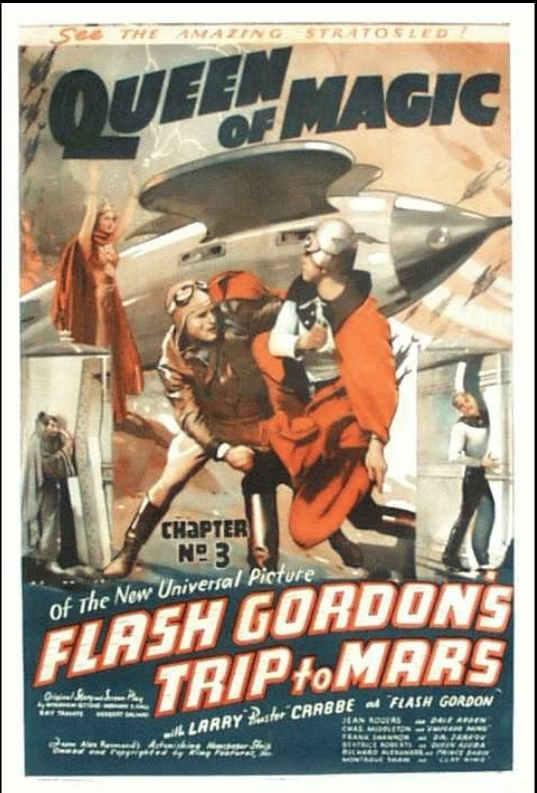

The original germ for the story was a sequence in Raymond’s Sunday strip about Flash’s encounter with Azura, Queen of Magic, who tries to lure him from Dale with an amnesia drug called lethium.

Note that this sequence, like the rest of Raymond’s stories in his strip, is set on Mongo, not Mars.

The serial’s Azura (Beatrice Roberts; not to be confused with the same-named showgirl who married Robert Ripley) differs greatly from her comic strip inspiration. She is more mature, has little romantic interest in Flash, and wields actual magical powers. While her comic strip predecessor employs potions to get what she wants, the film Azura uses a magical talisman, in the form of a white sapphire, to enable her to vanish in a cloud of white smoke and materialize elsewhere. It also gives her the power to transform people into living clay before teleporting them, with a wave of her hand, to the Clay Caves.

The serial’s vision of Mars differs from contemporary popular conceptions of the planet. There is no mention of Martian canals or moons. Instead we see desolate rock formations, caverns of living clay men, forests of gnarly trees, and most significantly, Queen Azura’s scientifically advanced domain. The soundtrack, largely from Franz Waxman’s score for Universal’s The Bride of Frankenstein, fits extremely well to the action.

Chapter One, “New Worlds to Conquer,” literally picks up where the previous serial left off, with the major actors resuming their roles. Our protagonists, Flash (Buster Crabbe), Dale Arden (Jean Rogers), and Dr. Alexei Zarkov (Frank Shannon), are still on the rocket ship speeding back from the planet Mongo, although Dale’s hair color has somehow changed in mid-flight from blonde to brunette!

However, it is not long after their return home, that Earth is again under attack from space. Zarkov traces the threat to Earth to a mysterious beam of light originating from outer space, and destroying our atmosphere. As in Flash Gordon, two years earlier, Flash, Dale, and Zarkov fly off to find the source of the threat and put an end to it. This time they are accompanied by newspaper reporter Happy Hapgood (Donald Kerr), who has stowed away on the ship and provides comic relief, to the chagrin of many critics

Flash and his companions crash land on Mars, where the beam originates, in the aptly named Valley of Desolation, seek shelter from Azura’s “Death Squadron” in the Clay Caves, and encounter the Clay People, who, in a visually memorable scene, accompanied by Franz Waxman’s “Danse Macabre” from The Bride of Frankenstein (1932), materialize out of the cave walls.

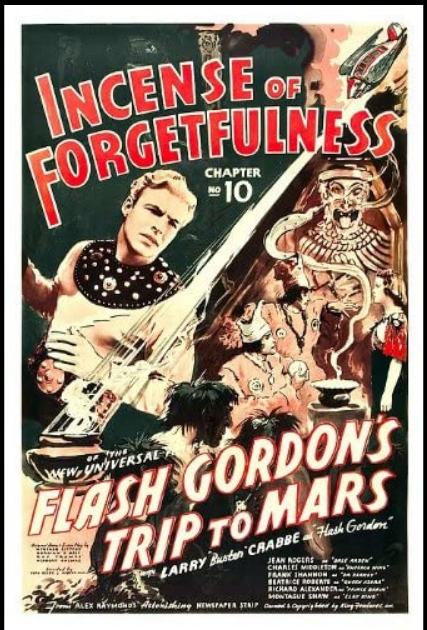

They soon encounter Ming the Merciless (Charles Middleton), even more satanic than before, who has escaped a fiery death on Mongo. He has a new ally in Queen Azura, who, with him, is using a huge elaborate-looking mechanism, a “nitron lamp,” to project the destructive beam to earth. The result is atmospheric mayhem as the apparatus drains our atmosphere of a substance called “nitron” (doubtless an early form of “unobtainium”). While Azura wants to use the extracted nitron to wage war on the Clay People, by employing its explosive properties, vengeful Ming is only intent on destroying the earth.

Each subsequent chapter begins with a synopsis of the previous one, presented as cartoons on a televisor screen, in a nod to the characters’ comic strip origins by Alex Raymond. The artwork is not Raymond’s, though, and was apparently sketched from stills taken from each previous episode.

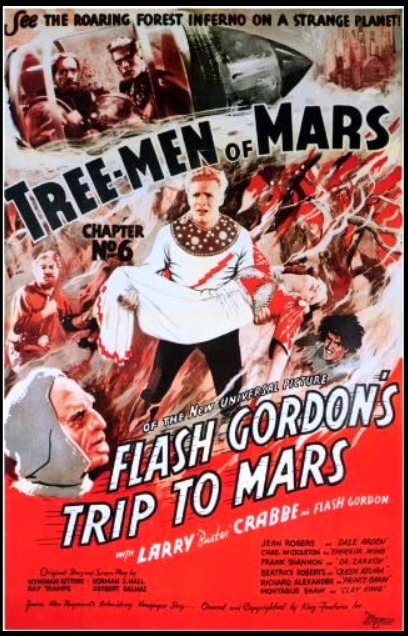

The storyline is more well-integrated than the one in 1936, with Flash encountering and re-encountering the different Martian kingdoms. The Clay King (Montague Shaw), at first seemingly an enemy, turns out to be quite sympathetic. Shaw gives a touching performance, even from behind the rubber mask he wears. The king of the Fire or Tree people (Anthony Warde) is himself unmemorable but the bleak, labyrinthine forest of twisted trees is unforgettable.

The Tree People possess the black sapphire that counteracts the queen’s powers. Flash and his associates discover that despite their primitive appearance, they have offensive weapons in the form of ray projectors. While there they meet Prince Barin (Richard Alexander), an old ally, formerly of Mongo.

Although this serial’s budget was about half that of its 1936 predecessor, it has a more polished and coherent look. While the first and third serials have a rather historical appearance, based on Alex Raymond’s drawings, in Trip to Mars the sets, costumes and backdrops of Azura’s palace and power house have present a futuristic vision with their sliding panel doors, ray machines, and imaginative matte paintings of a Martian city. Despite the crude special effects, it all manages to invoke an unworldly sense of wonder.

Light beams of all sorts occur throughout the chapters. From the nitron beam, to the light bridge to Azura’s palace, to the disintegrator rays used by the Tree People and by Ming, they provide a kind of leitmotif (pun intended). Even Azura’s throne is illuminated by sunbeams coming in through a high window.

As in the previous serial, the plot follows the classic “hero’s journey.” However the stakes are quite different. In the previous serial, Flash’s main objective was to protect Dale from Ming and escape from Mongo. Here, he must save the earth from total destruction. In addition he must remove Azura’s curse from the Clay People and restore them to their normal bodies.

Flash and his companions do not remain passive prisoners, as in the previous serial, but take a more active stance throughout. Even Dale, at one point, commandeers a stratosled and uses it to save Flash.

These low-flying, rocket-powered “stratosleds” were not in the original strip, but do resemble Burroughs’s Barsoomian “fliers.” They are another part of the setting and visuals that set it apart from the previous serial and also the third one (1940’s Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe).

A major question is why the screenwriters moved the locale to the planet Mars. It is a common misconception that the reason was to capitalize on the panic following Orson Welles’s War of the Worlds radio show in October of 1938. When they take off for Mongo, Zarkov is surprised to discover, near the end of the first chapter, that the nitron beam is actually coming from Mars, resulting in a last minute change of direction. This may have suggested to later audiences and critics that the change hadn’t been planned in advance.

But the serial was released months earlier, in March of that year, long before the radio broadcast. The confusion may in part be due to the release of the quickly edited feature length version to capitalize on the Welles radio drama, shortly after the radio broadcast. This feature version was titled Mars Attacks the World. But that doesn’t explain why the previously released complete serial was set on Mars in the first place.

Some have suggested it was done so the movie-going public would not think it was a re-release of the first serial under a new title. Or possibly the change of setting was to enable the designers to depart from Raymond’s visuals and enable them to do something quite different and futuristic looking.

Then again, the answer may lie in the success of a serial that came out in 1935, a year before Flash Gordon. Much of the imagery may well have been inspired by the Mascot serial, The Phantom Empire with its “scientific” civilization of Murania, 25,000 feet underground.

Like the other Flash Gordon serials, Buck Rogers, The Undersea Kingdom, and for that matter, The Wizard of Oz, The Phantom Empire was a product of the Great Depression, and movie audiences were being treated to such fantasies set in imaginary worlds.

The costumes and sets of the “scientific city of Murania” were quite visionary. Murania featured televisor screens for remote audio-visual communication and a futuristic cityscape of spires, domestic bridges and roving searchlights. There were robots, ray guns, a 25,000 foot tubular elevator and a “radium reviving chamber” even capable of reviving the dead. It was ruled by the disdainful Queen Tika (Dorothy Christie). Her royal guard or “Thunder Guard” were garbed in long cloaks, helmets, and lightning bolt chest emblems.

Unlike the primitive, historical-looking sets and costumes in 1936’s Flash Gordon, Trip to Mars similarly features futuristic cityscapes, high-speed tubular subways, televisor screens, paralyzing and disintegrating rays, and a healing chamber, which restores a wounded Happy Hapgood back to health. The arrogant Queen Azura, like Tika, has a royal guard or “death squadron” who also wear long cloaks, helmets, and lightning bolt chest emblems. Gene Autry had a couple of comic sidekicks in Phantom Empire and it may not be coincidental that in the Mars serial, Flash acquires a comic sidekick, for the first and last time.

In both serials the ruling queen, who had been the chief enemy of the protagonists, exhibits a marked character change toward the end, as each sacrifices herself to save others. Tika saves Gene Autry and his companions from the out-of-control destructive ray machine set in motion by her traitorous chancellor, Lord Argo (Wheeler Oakman). As Murania literally melts away, Tika insists Autry and his companions leave her and go to the surface. She watches on the televisor until they reach the entry cave, and opens the secret entrance to allow them to escape. Despite Autry’s pleading with her to escape to the surface with them, she insists on remaining behind to die with Murania.

Similarly, as Azura lies dying, the victim of her own death squadron sent by Ming, she gives her magical white sapphire to Flash and instructs him how to lift the clay curse. Despite Flash’s pleading with her to come with him, she insists on remaining behind to die.

Interestingly, the ray machine that destroys Murania was set in motion by Lord Argo, played by Wheeler Oakman. At the end of Trip to Mars, Ming is presumably destroyed in the disintegration chamber by his chief minion Tarnak, also played by Wheeler Oakman. Coincidence? Typecasting?

Some critics have charged that the serial’s last few chapters are padded, but that is arguable. Most serials have their conflicts resolved in the final two chapters, but that’s not the case here.

The nitron lamp is disabled by chapter nine, and with Azura’s death in chapter thirteen, the Clay People are restored to flesh and blood. Flash and his cohorts have achieved their goals but their victory is temporary. The diabolical Ming, now insane with anger and intent on destruction, is still at large and threatens to repair the lamp, attack the Clay people and destroy the earth.

Whereas the Phantom Empire essentially ends with the death of Tika, Trip to Mars continues to a second climax with the defeat of Ming in the final chapter. On the way, there is a moving scene in which the clay curse is finally lifted. Subsequently, one of Azura’s soldiers recognizes his brother, who he had believed to be dead, now restored to his normal body. With the help of this Martian soldier, Flash is able to disrupt Ming’s coronation as the new King of Mars. And when an enraged Ming threatens to destroy Mars as well as earth, in retaliation, Tarnak turns on him and forces him into the disintegration room. It’s the end of Ming, until, of course, his unexplained return in Flash Gordon Conquers the Universe! But that’s a story for another time.

If Trip to Mars reflects themes and images from the Phantom Empire, its imagery, in turn, can be seen reflected in media science fiction down through the decades. The direct parody, Flesh Gordon (1974), concerns the effects on earth of a “sex ray” from Mars. The X-wing dogfights in Star Wars and its sequels recall the air battles between the Martian stratosleds. Futuristic sets with sliding doors can be seen in numerous films and shows from Space Patrol to Forbidden Planet to Star Trek. And a close look at the Martians reveals the inspiration for Spock’s eyebrows.

Flash Gordon continues to fly on in popular culture. But our current problems in the real world with heat, hurricanes, and floods come from here on earth, not from Mars.

[Lee Weinstein’s website is: https://leestein2003.wordpress.com/]

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

When I go back and watch the Flash Gordon serials, I’m always a bit surprised at how ambitious they actually were, especially given the constraints they had to operate in.

When I was attending college at Purdue University back in the mid 70’s, I stayed in one of the dorms. (Cary Quad. Strangely enough, this is the same dorms that Mercedes Lackey stayed in when she attended Purdue several years before me.) Television reception was spotty, as there were no local TV stations: an antenna was erected outside of town and directed toward Chicago to pick up their broadcasts as the source for cable TV. That included WGN, channel 9.

Sunday mornings, some of us would gather in the commons area outside the cafeteria before breakfast, turn on the TV, and watch episodes of Flash Gordon on WGN, with commercial breaks with “Linn Burton, for Bert Waimann, your TV Ford Man. 3535 North on Ashland Avenue.”

Wonderful article, Lee. It brought back many joyous reflections and memories of my childhood, and the dreams that inspired my growth to emotional maturity.

Thanks Lee, for the wonderful article. i love old serials. I missed chapters of various ones at the theater (not enough money in our family to go to the movies every week) so with the advent of home video, I have been catching up. Flash is top of my list, right next to Fighting Devil Dogs. I have yet to see all of Africa, with its winged men.