The DDOS Panel at Readercon expressed caution and reassurance, while circling the heart of what Story is, and whether AI could ever do it well.

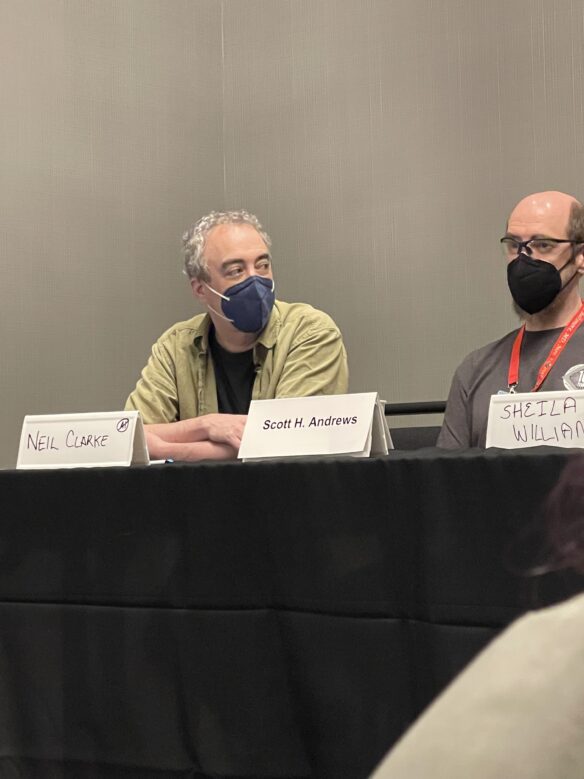

By Melanie Stormm: On Saturday, July 15, 2023, a panel of SFF editors, writers, and experts convened to discuss the current situation and approaches used to address the waves of AI spam submissions. The participants were John P. Murphy, current SFWA vice president; Matthew Kressel, author of King of Shards and creator of the Moksha system; Scott H. Andrews, editor of Beneath Ceaseless Skies; Sheila Williams, editor of Asimov’s, and the editor for Clarkesworld, Neil Clarke.

The panel expressed both uncertainty and reassurance. Writers looking to sell their short fiction to the genre’s most celebrated publications need not worry that months of painstaking labor can be outdone by an AI submission cooked up with the click of a mouse. Yet. AI fiction offerings are just plain terrible and terrible in new and innovative ways not yet discovered by humans. That’s the good news.

Particularly inspiring were the alacritous approaches that award-winning editor Neil Clarke (As Seen On TV), and award-nominated writer, editor, and creator of the Moksha submissions system, Matthew Kressel, have developed to address the crisis that the burst of AI spam submissions has created. Stretching over all of this, a pall of uncertainty.

Maybe pall isn’t the right word. Maybe describing the uncertainty as an ocean through which we all move would be more apt. Or perhaps it would be better to say the fish themselves are the sources of uncertainty.

If you’ve been hiding under a subaquatic rock or writing a book—two acts that produce similar outcomes—forget the fish for now and let’s catch you up on things.

The Swarm

In February 2023, one of the highest-paying markets for short speculative fiction closed to submissions for a then undetermined period for the first time since opening in 2006. Spoilers: it was Clarkesworld magazine. A swarm of five hundred-plus AI-written stories overwhelmed a system that necessarily relies on reading to discover new stories.

Clarkesworld was not alone. Sheila Williams experienced an onslaught of AI subs. Asimov’s uses the same submission system designed by Neil Clarke. Instead of slush readers digging through the seven hundred or more story submissions Asimov’s receives monthly, Williams personally handles each story.

In April, AI submissions initially peaked for Asimov’s. Things improved in May, but by June, the submissions shot up again; over 235 were AI spam submissions. When the media interviewed Williams in early spring, she reflected that she still had a sense of humor about the whole thing. But later, when the Wall Street Journal knocked on her door, she had run out of jokes. “It isn’t as time consuming [for me] as it would be for someone who isn’t an expert, but it is awful…By the time the WSJ interviewed me, I was so annoyed. I had no humor. I want to spend that time looking for new writers.”

Editor of the award-winning online fantasy magazine Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Scott H. Andrews, has similar struggles. However, due to the uniquely narrow submission guidelines, Beneath Ceaseless Skies has been spared the mass swarm of AI spam submissions at the time of the panel. Instead, writers of AI-assisted stories targeted the publisher of literary adventure fantasy, a kind of submission on a level all its own.

Firefighters

Before detailing the responses editors and developers are creating to respond to the AI spam crisis, it’s advantageous to describe how the SFF short fiction donuts get made and the toll such submissions have on the process. One of the best descriptions of how human slush readers handle volume is in a viral Twitter thread by Matthew Kressel. The thread was written in October 2022, just one month before ChatGPT became popular.

The Moksha submissions system is used by over forty publishers to receive, reject, and accept fiction, non-fiction, and poetry from writers around the world.

In the thread, Kressel writes:

“Assuming a modest submission rate of 50 stories per day (which is pretty average for Moksha publishers), and an average length of 5,000 words, that’s 250,000 words per day, or approximately 2 novels per day…

Yes, most publishers hire slush readers to help them sift through incoming submissions, so let’s assume they have 10 readers total (which is more than average), that means each reader needs to read 25,000 words per day.

That slush reader, who is most likely an unpaid volunteer, has to read ~175,000 words per week, because people submit on weekends too (often more),

This while keeping their day job and trying not to estrange their significant other and hopefully having some time to eat and sleep and maybe even a moment to relax and unwind.”

For the record, the original prompt for Kressel’s post was explaining to new writers why publishers must issue many story rejections without comment. The moral is there isn’t enough time in the day, and slush readers and editors don’t necessarily read your entire story.

One of the first replies to this thread was that the answer to these swift and impersonal rejections was that AI should be fed previous submissions to sort and manage the volume of human submissions. As it turns out, Story is far more complex than many people know, and current AI can only do so much so well. It stands to reason that if AI can’t write a good story, it can’t recognize one.

During the panel, Sheila Williams illustrated such a point. “Twenty-five percent of submissions in June were AI. We had 935. I try to get rid of these very fast. Neil [Clarke] has designed something that helps me and has shared places with me to help me identify those submissions, but I’m faster than those places.”

For others, relying solely on human expertise to identify and extract AI submissions quickly became impossible.

By the numbers, Clarkesworld was slammed. According to Neil Clarke, Clarkesworld receives an average of 1100 monthly submissions. In December, after ChatGPT first achieved widespread use, Clarkesworld identified fifty AI spam submissions.

“These were unusual stories showing up,” Clarke said. “Bad in ways no human was bad before.”

In January, this number doubled to one hundred. By February 20, 2023, five hundred submissions hit Clarkesworld’s system. Fifty new AI submissions arrived the morning Clarkesworld announced its closure.

First, Neil Clarke, who has a professional background in computer science and designed the Clarkesworld submissions system used by several publications, made adjustments to the firewall and the software. “That was far more effective than we thought it would be,” Clarke said. By March, Clarkesworld reduced AI spam submissions down to about two hundred.

SFF stories have diligently shown us that the Empire Strikes Back, and so did the AI submissions. Neil Clarke concluded, “By May, they had figured out what we had done, and we were then up to seven hundred.”

That is seven hundred surplus AI spam submissions, not including the submissions blocked by the firewall and software defenses.

The Second Wave

Spammers in the second wave were no longer flying in the dark. They had Clarkesworld in their sites, and the internet became rich with posts guiding people on using science fiction prompts to send AI stories to Clarkesworld.

Other experts in network security, credit card fraud, and spam contacted Clarkesworld, giving tips and further advice on reducing attacks that have doubled Clarkesworld’s already high submission volume.

Clarke spoke to the nature of the submissions. “And that’s how I would qualify these. These are spam.” And yet Clarkesworld, Asimov’s, and other publications are reluctant to rely entirely on firewalls, software, and AI tools to identify and automatically ban suspicious submissions.

Suspicious submissions are now relegated to the bottom of the pile so that editors can quickly read and release or accept submissions from human authors. After all, many of these publications don’t accept simultaneous submissions. This means that when an author submits a work for consideration, they must either wait for the editor to respond before submitting it elsewhere or withdraw the piece if time goes on too long. This practice works, and in the wider writing world, genre magazines have some of the fastest and most considerate turnaround times in the business (and are among the highest-paying, too.)

The careful ways in which each panelist identifies and considers suspicious content speaks to how passionate they are about giving new authors a chance, but also how little AI tools can be trusted to identify AI. Detectors have falsely flagged authors for whom English is a second language as AI-generated content.

Another takeaway was how considerate editors are of their slush readers, frequently working to ensure first readers are spared having to wade through spam.

It’s no secret that more spam comes from a handful of geographical regions than anywhere else. While some have suggested banning submissions originating in those locales in the interest of the greater good, no editor on the panel wants solutions like this. For Sheila Williams, the chance to bring exciting new SFF stories from unknown writers worldwide is too important. She reads each suspicious entry first and bans only once she’s positive it’s AI.

Neil Clarke described the human toll. “This is a constantly evolving state; we’re in this never-ending battle. It’s a lot of extra work. It would be great if these were legit stories, but it’s very frustrating. I found [reading spam] was beginning to interfere with the way I was reading submissions. Being irritated is not a good state of mind to be in when evaluating someone’s work.”

In describing the specifics of his approaches, Clarke was decisively vague. Matthew Kressel echoed the same strategy of playing cards close to the vest. One thing is clear: the sources of the AI spam don’t want to write good SFF stories; they want to trick genre editors into handing over their wallets.

The Ceaseless Submissions at Beneath Ceaseless Skies

As seen at Beneath Ceaseless Skies, AI submissions pose a threat on more than one front. Beneath Ceaseless Skies is among the most respected and coveted publication credits in the genre today—a status that puts a target on its back for AI spammers. Still, within a niche genre, it occupies an ultra-niche space.

A writer with a few years of practice may quickly identify a character-driven story from a plot-driven one. Still, in a world where genre lovers cut their eye teeth on film and TV as much as on the written form, many readers and young writers aren’t aware of the difference.

BCS qualifies what it will publish in almost every category. BCS only publishes (1) character-driven (2) adventure stories that (3) take place in secondary world (4) fantasy settings that (5) exhibit technologies no more advanced than those available during the 1930s. Furthermore, (6) the stories must be literary in craft. This craft is characterized by an intentionality and awareness within the prose that takes years to master.

And editor Scott H. Andrews has to like it (7).

Beneath Ceaseless Skies receives an average of three hundred submissions each month. They currently have five first readers, but Andrews reads the first page or so of every submission before assigning them to first readers. Once ChatGPT became more mainstream, Andrews started seeing an influx of submissions with cover letter mentions that the stories had been written with the assistance of AI. Andrews’ stance on AI submissions, assisted or otherwise, is informed by ethical and legal grounds. None of these submissions could ever be seriously considered for publication. Still, with curiosity and prudence, Andrews took a closer look at these new offerings.

Andrews explained there are many ways an author might use AI to “assist” a story; some are less harmful. Spellcheck is one, Grammarly is another. He and Matthew Kressel both warned against over-reliance on apps like Grammarly, which in the wrong hands, can flatten a writer’s voice and turn strong writing into hollow, mediocre text. These AI-assisted submissions weren’t specific as to how authors used AI in creating the story, but it was quickly apparent to Andrews that it went beyond Grammarly.

“Even though at BCS I’m not seeing the spam ones so much, I’m seeing the assisted ones, I still felt a sheen in those that was like nothing I’ve ever read from a human writer,” says Andrews.

By his description, AI-assisted stories sound slightly better than those that qualify as spam but also present different ethical and legal questions.

Andrews says: “I had to think of what exactly I should say. Different folks have different views so I fumbled around a bit and saw some things that Neil [Clarke] had written. I went with the definition that the US Copyright office put out this spring. Their quote was something to the effect that ‘the traditional elements of authorship can’t be done by a language model.’”

An AI approach to “writing” that relies on Language Learning Models is not copyrightable. The author doesn’t own the story and hence cannot license it to a publisher.

Legality feels like a firm foundation on which to build a stance for or against AI-assisted work, but even here, the ocean injects uncertainty.

“Some zines in our field are publishing LLM-created fiction anyway; it’s unclear how they’re handling the legal side of things,” Andrews points out. “The legal status would change if courts or laws deemed these LLMs’ use a legal fair use or deemed LLM-created works copyrightable.” The decisions of the Supreme Court or US Copyright Office are beyond any SFF publisher’s control.

Beneath Ceaseless Skies updated submission guidelines in March to reflect that AI-assisted works were unwelcome. Moksha also offers users an option that requires writers to declare if the stories they’re submitting are created using AI, and BCS avails itself of a similar tool.

The result? Cover letters stopped declaring AI assistance while stories containing that unnatural sheen continued to flow in. At the time of this writing, BCS has also seen an uptick in spam submissions.

Uncertain Fish

AI spam and AI-assisted submissions have threatened our publication communities in multiple ways, and all involved agree this is far from over. But it’s not the AI that poses a threat; it’s the humans involved at nearly every level that makes it so malignant. Enter the uncertain fish from earlier.

LLMs are fed copyrighted material at the developer level without authors’ permission. Regardless of legality, taking and using something without someone’s permission is stealing.

On Saturday, July 22nd, Matthew Kressel tweeted:

“None of the so-called commitments by the seven AI companies addresses illegal scraping and theft of copyrighted content. Why? Because their business models would collapse if they had to pay people for the terabytes of content they are stealing.”

Most SFF writers shudder at thinking of LLMs illegally scraping their published work to populate AI stories, crappy or otherwise. But published work isn’t all that’s exposed to scraping.

When interviewing Kressel for this post, he highlighted the following: “The issue we have now…is that data is forever. Previously, when you submitted a paper manuscript in the mail to a publisher, it is most likely going in the dump when they’re done…But now, it’s easy to keep stuff around forever.”

In other words, Kressel had to take specific strides on behalf of Moksha to protect unpublished and rejected submissions from illegal scraping. Who scrapes what is an ethical call by developers who often have their own best interests at heart. Writers should not assume the content of their Google Doc files are safe, although Kressel hasn’t personally stopped using Google Docs just yet. “Moksha’s manuscripts are locked behind an encrypted firewall, only accessible by the publisher, but even then, we need to have firm safeguards.”

Who scrapes what threatens emerging writers and SFF readers, too. Many writers make their name writing short fiction. Getting publication in top mags is a path to attracting agents and publishing longer works either independently or traditionally. But agents and publishers are only part of a writer’s career path—readers are the most essential. Publishing short fiction, especially in publications that make work available eternally online, can allow writers to build readership quickly. A reader who discovers a writer could access several of their stories with a mouse click and become a dedicated fan.

Without legal protections, all of this is scraped for free. Established writers may be the most prone; the more they’ve published, the more their unique voice can (and is) being replicated without permission. Sarah Silverman is among the first to sue OpenAI (the creators of ChatGPT) and Meta over copyright violations. Don’t hold your breath on whether this amounts to robust protections for writers.

SFF is experiencing a new golden age created partly by online publication opening doors to a global readership. Global readership speaks not only of previously unreached audiences on the Asian and African continents but also of reaching more readers on continents that SFF already enjoys community. Rural and remote areas often lack bookstores offering copies of the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction or Clarkesworld. Online presses have carried some of our most loved stories to excited new fans who would not otherwise have access to them.

Several SFF editors and writers have expressed worry over the future of online SFF publications if authors don’t feel sufficiently protected. If authors start preferring print-only models or having stories locked behind bullet-proof paywalls, the inroads our community has created could crumble quickly. Whatever our disputes, this community exists because there are enough positive, trusting relationships between writers, readers, and publishers.

So what about all the bad AI-generated stories? Who are they, and where do they get off? The SFF ocean is flooded with schools of spammers who don’t come from the global SFF community.

“They have no idea there’s a community,” said Sheila Williams. “This is not their dream. They just found a way to make some money.” Some submissions address Williams with notes saying, “I heard about your side hustle. Please send money to my Western Union.”

The source of AI-assisted work is more challenging to parse. Undoubtedly, outsiders who care as much for the genre as they do the firewalls they’re trying to evade are responsible for some, but not all.

Combing subreddits and SFF discord servers yields a surplus of discussions on how to use AI to do some of the hard work of writing a story, but yelling at these writers isn’t the right approach either. It takes a long time to learn how to write stories and even longer to do it reliably. Writers don’t get to pause life, and some are understandably tempted by the lure of making this easier. AI aside, the internet is chockfull of cobbled-together courses, books, and free eGuides that promise to make the road to publication fast and easy. Some of them are even good, but those don’t promise to make it easy, just clearer.

Some see LLMs as a way of teaching themselves how to write better science fiction. Clarke asked: “Do you really want to learn from something that stole other writers’ work?”

The ethics of AI assistance needs to be more explicit in other areas. Screenwriters with the Writers Guild of America stipulated that they would allow for the use of AI only as it assisted them with their original work but drew a line against machine-generated storylines or dialogue qualifying as “literary material.”

AI is no small issue in the current writer’s strike. In 2017, the average full time writer made a yearly salary of just $20,000. A world where writers must share a byline with AI is terrifying as writers are isolated further from benefiting from their own trade. My Saponi mother would call this being put on a reservation.

The technological battle is ongoing, the legal one may take years to play out in courts and could reverse at any time, but the ethical issues are within our power to address.

Speaking outside of Readercon, some editors have suggested that the answer to this ethical attack on our community is more community.

Kressel says, “What I’d like to see is the SFF community coalesce around a set of core values, similar if not identical to Neil’s statement on AI. And I’d like to see SFWA and others release draft language, similar to how they offer boilerplate contracts, to (a) protect authors, (b) protect publishers, and recognize that both are necessary for a healthy community going forward. I understand the situation is rapidly evolving, but that doesn’t mean we can’t affirm our values now.”

Just a day after Kressel made that (yet unpublished) statement, SFWA encouraged members to read and sign the Author’s Guild open letter. This development was a promising community response. The current SFWA vice president and author, John P. Murphy, served as the moderator for this panel. Salient fact: he holds a doctorate in Machine Learning.

In all of this uncertainty, it’s clear that we must stick our necks out and protect the relationships that make our community possible, even if the immediate threat is the growing amount of spam that continues to overwhelm our publications. AI assistance is not a threat from outside our community but comes from within; it’s a longer-term issue.

Can AI Tell Good Stories?

In 1972, George R.R. Martin published an essay about chess-playing computers in Analog. It was titled “The Computer Was A Fish,” and Sheila Williams referenced it during the panel. The moral of the essay was that chess-playing computers were terrible. In the last year, we’ve seen the chess world rocked by the illegal use of AI that gave players unfair advantages in tournaments. Leaders developed better ways to identify cheating and more severe repercussions for violations to protect the integrity of the game.

It is still unclear whether Language Learning Models and the other AI forms that will replace them will become incredible at telling stories that fascinate human readers. Most editors doubt AI can develop the capacity, yet SFF readers and writers never get tired of asking, “What if?”

One attendee at the DDOS panel posed a hypothetical question to the panelists: “What if a developer takes it as a challenge to create AI that writes a story that wins a Hugo?”

“That’s a wonderful story,” Neil Clarke mused.

Sheila Williams interjected, “—That a human being came up with.”

Thanks to the DDOS panelists, John P. Murphy, Matthew Kressel, Scott H. Andrews, Sheila Williams, and Neil Clarke. Thanks also to Bernard Steen for providing photos and to PJ T. de Barros for providing an audio recording of the panel as reference.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

Thanks for this. Good summary of where things are at now.

what a nightmare

Very interesting article. I wonder if magazines are going to be forced into a model were new authors have to pay a fee in order to get into the slushpile?

@Max Andersson

I’m sure they want to avoid that. Most genre writers have been taught that legitimate publications do not charge for submissions. (This is unlike the literary fiction field, where a lot of publications have a submission fee. And journals, where submission fees have become accepted.)

On top of that, editors who want to diversify the field know that a submission fee would be a huge burden on disenfranchised writers, writers from other countries, etc.