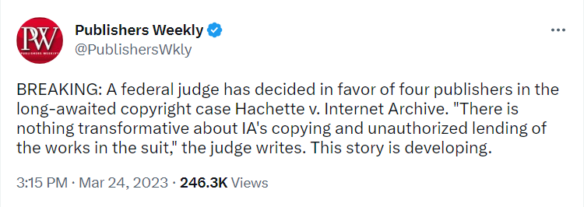

Publishers Weekly has tweeted breaking news about a decision in the publishers’ suit against the Internet Archive:

A copy of the decision can be downloaded from CourtListener: gov.uscourts.nysd.537900.188.0.pdf (courtlistener.com)

EXCERPTS FROM THE DECISION. John G. Koeltl, District Judge of the U.S. Southern District of New York, granted summary judgment based on the record, as was requested by both sides. His analysis of the case is illustrated in the following quotes from the decision.

The plaintiffs in this action, four book publishers, allege that the defendant, an organization whose professed mission is to provide universal access to all knowledge, infringed the plaintiffs’ copyrights in 127 books (the “Works in Suit”) by scanning print copies of the Works in Suit and lending the digital copies to users of the defendant’s website without the plaintiffs’ permission. The defendant contends that it is not liable for copyright infringement because it makes fair use of the Works in Suit.

…In the two years after the NEL, IA’s user base increased from 2.6 million to about 6 million…. As of 2022, IA hosts about 70,000 daily ebook “borrows.” …

…IA argues, however, that this infringement is excused by the doctrine of fair use. This doctrine allows some unauthorized uses of copyrighted works “to fulfill copyright’s very purpose, ‘[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful Arts.’” Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569, 575 (1994). While rooted in the common law, fair use is a statutory exception to copyright infringement. The Copyright Act of 1976 provides that “the fair use of a copyrighted work” for “purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright.” Id. § 107. “In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use,” the Copyright Act directs courts to consider the following factors:

(1) the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

(2) the nature of the copyrighted work;

(3) the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

(4) the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. 17 U.S.C. § 107. The four factors are not exclusive, but each must be considered in a “case-by-case analysis,” with the results “weighed together[] in light of the purposes of copyright.” Fox News Network, LLC v. TVEyes, Inc., 883 F.3d 169, 176 (2d Cir. 2018). Fair use presents a mixed question of law and fact and may be resolved on summary judgment where, as here, the material facts are undisputed.

FIRST FACTOR. In this Circuit, consideration of the first factor focuses chiefly on the degree to which the secondary use is “transformative.” Id. A transformative use “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message, rather than merely superseding the original work.”

…There is nothing transformative about IA’s copying and unauthorized lending of the Works in Suit.7 IA does not reproduce the Works in Suit to provide criticism, commentary, or information about them. See 17 U.S.C. § 107. IA’s ebooks do not “add[] something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the [originals] with new expression, meaning or message.” Campbell, 510 U.S. at 579. IA simply scans the Works in Suit to become ebooks and lends them to users of its Website for free. But a copyright holder holds the “exclusive[] right” to prepare, display, and distribute “derivative works based upon the copyrighted work.” 17 U.S.C. § 106. An ebook recast from a print book is a paradigmatic example of a derivative work. Authors Guild v. Google, Inc., 804 F.3d 202, 215 (2d Cir. 2015) (”Google Books”) (citing 17 U.S.C. § 101). And although the changes involved in preparing a derivative work “can be described as transformations, they do not involve the kind of transformative purpose that favors a fair use finding.”…

The first factor also directs courts to consider whether the secondary use “is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes.” 17 U.S.C. § 107(1)…

…IA exploits the Works in Suit without paying the customary price. IA uses its Website to attract new members, solicit donations, and bolster its standing in the library community…. Better World Books also pays IA whenever a patron buys a used book from BWB after clicking on the “Purchase at Better World Books” button that appears on the top of webpages for ebooks on the Website…. IA receives these benefits as a direct result of offering the Publishers’ books in ebook form without obtaining a license. Although it does not make a monetary profit, IA still gains “an advantage or benefit from its distribution and use of” the Works in Suit “without having to account to the copyright holder[s],”… The commercial-noncommercial distinction therefore favors the Publishers….

IA makes a final argument that the first factor favors fair use because, according to IA, by reproducing and distributing only ebook editions of print books that were lawfully acquired, IA furthers the goals of copyright’s “first sale” doctrine. This argument is without merit….

… Acknowledging this, IA refashions a first sale argument within its fair use analysis. IA argues that although “Section 109 does not expressly encompass the reproduction right, neither does it abrogate the common-law principle favoring the ability of the owner of a copy to freely give, sell, or lend it.”…. But IA points to no case authorizing the first recipient of a book to reproduce the entire book without permission, as IA did to the Works in Suit….

… Nor does IA’s promise not to lend simultaneously its lawfully acquired print copies and its unauthorized reproductions help its case. As an initial matter, IA has not kept its promise. Although the Open Library’s print copies of the Works in Suit are non-circulating, IA concedes that it has no way of verifying whether Partner Libraries remove their physical copies from circulation after partnering with IA…. To the contrary, IA knows that some Partner Libraries do not remove the physical books from their shelves, and even if a Partner Library puts a physical book into a non-circulating reference collection, it could be read in the library while the ebook equivalent is checked out….

… The crux of IA’s first factor argument is that an organization has the right under fair use to make whatever copies of its print books are necessary to facilitate digital lending of that book, so long as only one patron at a time can borrow the book for each copy that has been bought and paid for. See Oral Arg. Tr. 31:10-15. But there is no such right, which risks eviscerating the rights of authors and publishers to profit from the creation and dissemination of derivatives of their protected works….

The first fair use factor strongly favors the Publishers…

SECOND FACTOR. The second fair use factor directs courts to consider “the nature of the copyrighted work.”

…IA argues that because most of the Works in Suit were published more than five years before IA copied them, IA has not interfered with the authors’ “right to control the first public appearance of [their] expression.”… Published works do not lose copyright protection after five years….

THIRD FACTOR. Under the third fair use factor, courts consider “the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole.” 17 U.S.C. § 107(3). IA copied the entire Works in Suit and made the copies available for lending….

It is true that copying an entire work is sometimes necessary to make a fair use of the work… In this case, however, IA copied the Works in Suit wholesale for no transformative purpose and created ebooks that, as explained below, competed directly with the licensed ebooks of the Works in Suit. IA’s wholesale copying therefore cannot be excused, and the third factor weighs strongly in the Publishers’ favor…

FOURTH FACTOR. The fourth fair use factor is “the effect of the [copying] use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work[s].” 17 U.S.C. § 107(4). This factor focuses on whether a secondary use “usurps the market for the [original] by offering a competing substitute.”

… In this case, there is a “thriving ebook licensing market for libraries” in which the Publishers earn a fee whenever a library obtains one of their licensed ebooks from an aggregator like OverDrive…. This market generates at least tens of millions of dollars a year for the Publishers…. And IA supplants the Publishers’ place in this market. IA offers users complete ebook editions of the Works in Suit without IA’s having paid the Publishers a fee to license those ebooks, and it gives libraries an alternative to buying ebook licenses from the Publishers. Indeed, IA pitches the Open Libraries project to libraries in part as a way to help libraries avoid paying for licenses….

… It is also irrelevant to assessing market harm in this case that IA and its Partner Libraries once purchased print copies of all the Works in Suit. The Publishers do not price print books with the expectation that they will be distributed in both print and digital formats,…

… Finally, the Court must consider “the public benefits [IA’s] copying will likely produce.” Andy Warhol Found., 11 F.4th at 50. IA argues that its digital lending makes it easier for patrons who live far from physical libraries to access books and that it supports research, scholarship, and cultural participation by making books widely accessible on the Internet. But these alleged benefits cannot outweigh the market harm to the Publishers….

SUMMARY ANALYSIS. … Each enumerated fair use factor favors the Publishers, and although these factors are not exclusive, IA has identified no additional relevant considerations. At bottom, IA’s fair use defense rests on the notion that lawfully acquiring a copyrighted print book entitles the recipient to make an unauthorized copy and distribute it in place of the print book, so long as it does not simultaneously lend the print book. But no case or legal principle supports that notion. Every authority points the other direction. Of course, IA remains entitled to scan and distribute the many public domain books in its collection. See Pls.’ 56.1 ¶ 294. It also may use its scans of the Works in Suit, or other works in its collection, in a manner consistent with the uses deemed to be fair in Google Books and HathiTrust. What fair use does not allow, however, is the mass reproduction and distribution of complete copyrighted works in a way that does not transform those works and that creates directly competing substitutes for the originals. Because that is what IA has done with respect to the Works in Suit, its defense of fair use fails as a matter of law. …

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

My admiration for the Internet Archive is boundless, which is why I remain astonishingly mad at them for endangering their existence with this almost prima facie illegal idea.

Clickity

Doubleclick!

Pingback: Judge Decides Against Internet Archive by sohkamyung - HackTech

@Ray: my feelings exactly

Excellent news!

@ Ray Radlein & Doctor Science

Thirded with great passion.

@Ray: Exactly. How IA thought they were not going to lose in court boggles my mind.

@PhilRM–They were relying on a novel interpretation of Controlled Digital Lending, one that skipped very lightly over the “controlled” part, basically omitting the “control” altogether. They apparently did not realize that in law, “novel” interpretations are almost always very dimly regarded.

This ruling doesn’t come as a surprise. Huge fan of IA but they really pushing it here.

A decision that surprised exactly no one who knows anything about copyright law.

I really enjoy Internet archive

The great thing about them especially since I am mostly housebound due to my seizures etc is that I can use it as the library it is to find books etc that are not available in many cases especially in ebook form (as I also have poor eyesight) When I find a book/ebook on Internet archive that I do enjoy I usually end up purchasing the ebook. If the library of Internet archive no longer exists I will more than likely not only have to purchase fewer books but therefore also recommend fewer books (as I only recommend books that I have read) in the online groups that I belong to.

TL;DR: This resembles as closely as possible how public libraries work and should thus not be illegal.

I think this decision is quite devastating. CDL is, IMHO, not illegal, and mimics closely how public libraries work. The difference: At IA, you can only lend a book for an hour, which is usually sufficient to search for a citation or quote. Plus, the “lending” is very much like what publishers do when you can view a purchased digital copy in their web viewer (which is usually not time-limited, thus even more convenient).

I think IA’s service is great for some books that are hard to find in paper libraries. Shutting this down would be a great disservice to the public. I think this is a balanced description of the issue:: https://www.theregister.com/2023/03/20/internet_archive_lawsuit_latest/

Good news!

I guess it’s time to start putting my money where my mouth is and figuring out what imprints those publishers use so that I can never buy anything from them again. (At least not for myself, I reserve the right to be a hypocrite when it comes to buying books for my partner)

How is IA not a public library?

A deeply frustrating situation all around. I use Open Library for research sometimes and losing it would be a real blow, but I can’t argue against the decision given the facts of the case.

@Alan–Public libraries don’t treat copyright law as a casual suggestion. IA’s “interpretation” of Fair Use and Controlled Digital Lending is not just novel but whackadoodle. No one familiar with copyright law e er thought this was likely to prevail.

I apologize for naivete, but why is the “at bottom” part so ridiculous?

I think we (society) do expect that if I own a book, it’s perfectly legitimate for me to change its location or format, as long as I’m not creating copies that compete with the owner’s right to sell. If there’s no caselaw to support this completely normal interpretation, the caselaw needs to change.

Or is it solely about whether IA lent versions without controlling further copying?

@Mark Hahn–

No, the right to to copy is literally what copyright is. There’s the fair use exception, but no, that doesn’t include the right to copy the entire copyrighted work. It does not include the right to lend that copy.

There is very limited exception to that, called Controlled Digital Lending. It applies to libraries that own single copies of very rare books, that can’t be replaced by just buying another copy from your favorite vendor.

It doesn’t support what IA does, buying or receiving a donation of a print book you can order from Amazon or any other retailer, and copying that, to lend the copy. If you think you have the right to do that with your personally owned copies of books, you are mistaken. You’re not likely to get caught and prosecuted or sued, but if you were to do it on a large scale, you would be.

Internet Archive has been doing it on a very large scale. And bragging about it. Making sure they couldn’t be overlooked or ignored.

They also, during the height of the pandemic shutdowns, they weren’t even limiting their lending to one borrower at a time per legally owned print copy. They’ve stopped doing that, but I don’t believe they’ve ever admitted that they didn’t have the legal right to do so.

That was waving a giant red flag in front of corporations who have always regarded digital publishing as a threat, not a way to reach more customers.

Many, many copyright lawyers, librarians, and even cooler heads in the publishing industry, would have much preferred IA had never waved that red flag, because once they did, major publishers really had to go after them.

Because yes, they were able to prove that IA’s activities did hurt their sales, which is mentioned in the decision of which you apparently only read the part after “At bottom…”

Pingback: Pixel Scroll 3/25/23 Pixel Is That Which, When You Stop Scrolling It, Doesn’t Go Away | File 770

I’m pretty sure it was the lending infinite copies stunt that brought the hammer down, and also eventually lost them the case. It ceded any possibility of a grey area they might otherwise have claimed. It was unspeakably foolish.

And, given the low average wage of authors and how deeply affected many of them are already by standard pirating, rather cruel.

Very interesting

Pingback: AMAZING NEWS FROM FANDOM: March 26, 2023 - Amazing Stories

Truly sad. What will happen to that portion of the IA collection that is not in copyright. An extraordinary resource for research … Extremely valuable for English and American Literature of the 19th Century.

An explorer cannot but be impressed by the treasures available to everyone in the world which would otherwise be hidden.

Audubon’s Birds of America. How else would one access this at home. (Yes there is the Bioheritage Library perhaps)

Is there any resource comparable for an individual who is not a University Student with specialised access to resources?

🙁

Is there any Government around the world that has been inspired enough to digitise the holdings of their libraries non-copyright material as a service to humankind ?

There are few Grand Visions and some that exist are under threat.

Sadly, as mentioned above, the publishers were pushed too far.

The court decision explicitly says IA can keep making available works in the public domain.

Pingback: Michael Tsai - Blog - Hachette v. Internet Archive

Pingback: Top 10 Stories for March 2023 | File 770

Pingback: File 770’s Most-Read News Stories of 2023 - File 770