By Martin Morse Wooster: Horror writer/director Larry Cohen was once the subject of a New Yorker profile, and the interviewer asked him how he still had a career when he was in his mid-sixties. Cohen explained that in Hollywood, no one cares what you did 20 years ago. The primary question producers ask is: what have you done lately? Keep coming up with salable projects and the people with money will keep giving it to you.

Having a long career in Hollywood is a lot harder than in other forms of publishing; you’ve got to have the relentless drive to pursue your vision and keep making sales. To an outsider, what is astonishing about J. Michael Straczynski’s career is that it has had a third act and may well be in the middle of a fourth. His career could have faded after Babylon 5. The roars that greeted him at the 1996 Los Angeles Worldcon (where, it seemed, every conversation had to include the words, “Where’s JMS?”) would have faded and he could have scratched out a living signing autographs at media conventions.

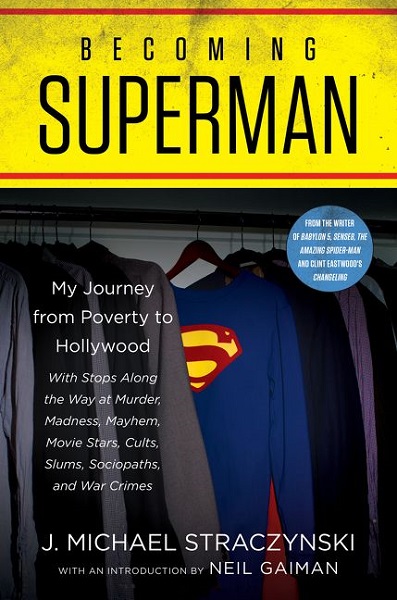

But instead, Straczynski pursues new projects, including his realization of The Last Dangerous Visions and a reboot of Babylon 5 currently under development at the CW. He tells his story in his memoir Becoming Superman, published in 2019.[1]

Straczynski has two purposes in his very readable autobiography: telling his life story and explaining why his parents—and particularly his father—were world-class jerks,

Do you think you have toxic parents? However badly your parents treated you, Straczynski’s were much worse. His grandfather who routinely killed and ate pigeons from the parks as a free protein source. His mother was committed to mental hospitals five times and underwent electroshock more than once.

His father, Charles Straczynski, is the book’s villain. The secret of the book—which I’m not going to reveal—is what he did in Poland to survive World War II. After coming to America, Charles Straczynski was a drunken jerk who beat his wife, beat his children, periodically moved between the east and west coasts to flee his creditors, and was, more frequently than not, in a perpetual drunken rage. By the time J. Michael Straczynski was 10, he had been in five schools.

Worst of all, Charles Straczynski ripped up his son’s comic books, which would have been quite valuable if. J. Michael Straczynski had kept them.

Straczynski’s refuge from his toxic father were comics. Two of the high points of a particularly dismal year came when Straczynski received the membership packets from Supermen of America and the Merry Marvel Marching Society.

“Our frequent moves had denied me the chance to make lasting friends,” he writes, “but as I covered the walls with posters of Superman, Thor, Captain America, Spider-Man, and the Hulk, everywhere I turned, the face of a friend was looking back at me.”

Straczynski also discovered science fiction paperbacks, beginning a lifetime of reading and talking about the field,

Becoming Superman is the story of a writer who made his own breaks and steadily rose in Hollywood thanks to years of producing copy at 10-20 pages a day. Straczynski sold The Complete Book of Scriptwriting to Writer’s Digest Books because he tried to find a book on writing scripts and couldn’t find one. At the time, Straczynski’s experience in Hollywood was very limited. He got some doors to open in Hollywood and kept them open through his talent.

Like most Hollywood memoirs, Straczynski has stories. My favorite was in his last assignment in animation, where, for the cartoon The Real Ghostbusters he had a script that made a reference to The Necronomicon. The suits said he had to change the book’s name because The Necronomicon was popular with Satanists. Straczynski tried to explain that the book was made up by H.P. Lovecraft. He lost[2] and decided to write an article denouncing the animation industry, which he sold to Penthouse. When their nonfiction editor asked him why he submitted the piece there, Straczynski said so that “tight-assed consultants and editors” who wanted to read what Straczynski wrote would have to buy “a magazine full of racy photos.”

Perhaps the saddest story in the book is when Straczynski got a job on Jake and the Fatman by noticing that star William Conrad, who did not play Jake, didn’t like to move very much. So he came up with a story where Conrad’s character is kidnapped. “He’s taken hostage and tied to a chair for the entire episode,” Straczynski said in his pitch.

Showrunner David Moessinger’s “eyes lit up like a Las Vegas slot machine. ‘That’s terrific!’ Moessinger said. “Bill hates to walk! He’ll love it!” Straczynski got the job.

Straczynski devotes three chapters out of 34 to Babylon 5. He tells us some things, including how hard it was to write all the scripts (except for one by Neil Gaiman) for Babylon 5’s last three seasons and how he had to deal with the mental breakdown of star Michael O’Hare after the first season. He credits Sandra Bruckner, head of the Babylon 5 fan club, for her help with O’Hare and other Babylon 5 stars who were in trouble. But there are some questions he glosses over, including what, exactly, Harlan Ellison did as the show’s “creative consultant.”

The reason Straczynski doesn’t dwell on Babylon 5 is that he wants to tell us about life after that show, including the three fallow years where everything he wrote was rejected: and he nearly quit writing. But Straczynski had long been interested in the story of Christine Collins, whose struggle to determine what happened to her son in 1920s Los Angeles ultimately led to exposing massive corruption in the Los Angeles Police Department.

Straczynski submitted his script to his agent in 2006. The agent sold the script to Ron Howard for $650,000, and Howard passed the script on to Clint Eastwood. Straczynski describes his meeting with Eastwood, when Eastwood to promised to film Straczynski’s script exactly as he wrote it.

Changeling appeared in 2008, but after the sale of his spec script in 2006, Straczynski’s plate was full, with credits on five other movies and stints as the lead writer on Spider-Man and Superman. A script he wrote on the friendship between Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Harry Houdini (which hasn’t been produced) sold for a million dollars. But the point of Straczynski’s readable and informative memoir is to tell writers that however successful you may become, there will always be lumps and down periods in your career which you will need to overcome.

“We have no control over who beats us up or knocks us down, or the obstacles that stand us and our dreams,” Straczynski concludes. “But we have absolute control over how we choose to respond.”

So the answer to how to deal with rejection or a closed door, Straczynski writes, is a simple one: “get up and keep fighting.”

[1] Thanks to able bookseller Michael J. Walsh for selling me a copy at the 2021 Capclave.

[2] The book in the episode was changed to “The Nameless Book.”

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

I enjoyed this book very much – thanks for the review

I read Becoming Superman right after it was released. The progressive revelations about Straczynski’s father were the stuff of nightmares.

An incredible, inspiring story – he just never gave up.