By Steve Vertlieb: Across a sea of stars and time lies a horror too terrible to endure…an evil Hell-Bound Train riding to infinity upon tracks immersed in darkness, careening toward midnight, consumed by madness…a terrible Opener of The Way to flights of fancy and depravity lost in translation, yet rediscovered in endless pages of classic fantasy rendered by one of the greatest, most enduring writers of the genre, Robert Bloch. One of the original circle of authors and students inspired by the eloquent lunacy of H.P. Lovecraft, Robert Bloch began his writing career in 1935 with a series of frightening short stories that soon assumed a poetic eloquence that rivaled Lovecraft in horrific intensity and originality. The crumbling pages of Weird Tales entertained these imaginative stories of witchcraft, mayhem and tales that witnessed madness. With fables such as “The Hungry House,” “The Cheaters,” “Yours Truly Jack The Ripper,” “I Kiss Your Shadow,” “The Dark Demon,” “The Faceless God,” “Beetles,” and “The Shambler From The Stars,” Robert Bloch quickly and effectively established himself as a master of the macabre, setting a standard of writing unequalled by any writer before or since.

Born in Chicago on April 5, 1917 to Jewish parents, Robert Bloch became an avid reader of pulp magazines and, in his teenage years, began a life transforming correspondence with Lovecraft who became his mentor, encouraging the young fan to write and develop his own fantastic fiction. At age seventeen he sold his first professional stories to Weird Tales and, with such lurid titles as “The Feast In The Abbey,” and “The Secret In The Tomb,” began to carefully establish his own fictional identity and style. In tribute to his young disciple, Lovecraft paid incomparable homage to the teenager by writing him into the text of his novel “The Haunter Of The Dark” as Robert Blake. After Lovecraft’s untimely death in 1937, Bloch continued to write for Weird Tales, as well as the science fiction themed Amazing Stories Magazine, quickly becoming one of the most widely read and popular authors of the genre.

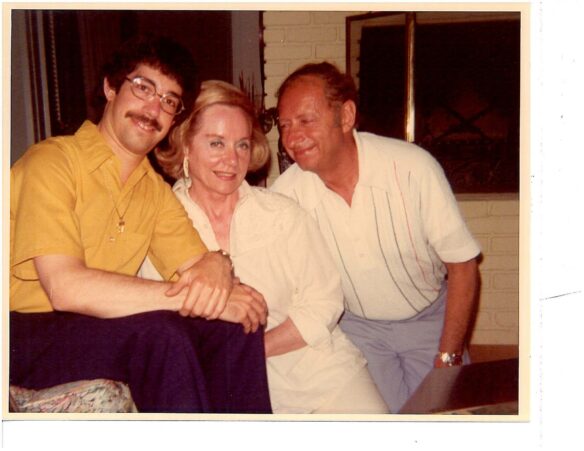

In his private persona, Bloch was a gentle soul with a huge heart who delighted in regaling audiences and friends with jokes and vaudevillian one liners. A student of motion pictures and the arts, he entered a hidden chamber within his soul when setting about creating the terrifying stories that solidified his reputation and career. A Mr. Hyde to the softer reflection of Henry Jekyll, the writer rarely shared his darker inspiration with his adored and adoring wife, Elly, who preferred to gloss over and forgive his celebrity, finding solace instead in his culture and humanity. For millions of readers of traditional horror fiction, however, Robert Bloch was the master of the macabre, a superb story teller whose hauntingly fanciful tales became the standard by which others were judged. His fertile imagination sired the stuff that unsettling dreams and nightmares are made of.

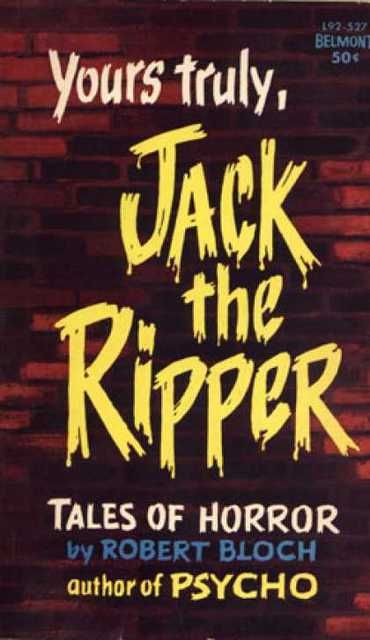

Admittedly an armchair psychologist, Bloch found the human psyche endlessly fascinating, infusing his characters with complex, disturbing behavioral patterns he could only imagine. An enthusiastic student of bizarre human behavior, he carefully crafted each characterization with dangerously woven personality flaws that lifted mere single dimensional protagonists from the printed page to uncomfortable realization. In his introduction to a paperback anthology, Yours Truly, Jack The Ripper, published by Belmont Books in January 1962, Bloch writes: ”My life as Jekyll has been commonplace in the extreme. I have a home, a family, a regular occupation, friends; a normal schedule of hobbies and amusements. Yet, Mr. Hyde is active, nonetheless. It is a partnership which has proved both pleasant and profitable — and it would ingratitude indeed if I allowed Dr. Jekyll to take the credit without proper acknowledgement to his alter ego. But the inspiration comes from Mr. Hyde. I fear, however, that Mr. Hyde must also share the blame for errors of taste and judgement. In his haste to affect some particular ghastly revelation, he has ignored many literary niceties. I can only submit that this is matter beyond my control.”

Bloch, along with the reader, has given away both his rational reasoning and will power, consciously sacrificing his higher instincts for the greater good of his imagination. As an actor of gentle or docile spirit studiously packs away his better nature in order to mine the trenches of his hidden demons, and more accurately capture the ugliness he must portray, either on screen or in the theater, the writer’s imagination floods his more spiritual sanctuary in search of the characters and stories lurking just beyond the fragile threshold of sanity. He must unleash Hyde at the expense of Jekyll, sleepwalking vicariously through the dungeons of depravity.

Sensitive to the duality of human nature, Bloch’s essay on “The Clown At Midnight” remains a classic of extraordinary perception. He asks the reader to visualize a circus clown performing within the restricted confines of a three ring tent. The surroundings are familiar, and the imagery comforting. Children of all ages laugh at the frantic behavior of the jolly clown adorned in frilly, loose fitting costuming. The circus performer cavorts with blackened teeth, his face pale and unrecognizable beneath the theatrical makeup that deftly conceals his identity. Now, as Bloch suggests, what would happen if you lifted that very same clown out of the familiar surroundings of a circus sideshow, and placed him alone on a deserted corner, standing solitary beneath a dimly lit street light? There, motionless and grinning beneath a soul less mask, he assumes the persona of a demonic and terrifying escapee from either an asylum for the criminally insane, or from the bowels of Hell. Sanity grasps tentatively at the bonds holding together reason as the veil that witnessed madness crumbles in horrifying confusion.

In his short story “The Hungry House,” (1951) a psychologically vulnerable couple move into an old mansion priced just a little too inexpensively. They quietly congratulate themselves on their shrewd negotiating skills, little realizing that the realtor was a bit too anxious to let the property go at such an unrealistic cost. It isn’t long before they begin to suspect that they aren’t alone in the property, for this is a troubled house, a disturbed structure whose malevolence conspires to consume them. It had never occurred to the couple that an alarming absence of mirrors within the dark walls of their new home might have been a forboding suggestion of danger to come. Reflections caught out of the corners of their eyes suggest a shadowy presence hidden just beyond recognition. Shaving mirrors shudder in vague, unholy perception, multiple and uninvited images shimmering in faded twilight. The house had once been inhabited by a vain, beautiful belle of the ball whose self adoration had all but consumed her. Mirrors adorned every corner of the house so that she could observe her own perfect loveliness. The years had finally passed her by but, for the mad and lonely soul who danced solitary within its walls, time had stood mercifully still. She danced into the very mirrors that had once caressed her, an old embittered hag whose frail skin had been torn to ribbons by the jagged daggers smashing about her. They said that her spirit still lived, and danced within those mirrors, mirrors discovered in a locked attic upon investigation of the shadowy house. For now, unleashed from her imprisonment, the tortured reflection of the haggard crone, withered and cruel, reached out from beyond the grave to invite others to join her…others who might come to worship her beauty, frozen in Hell.

“The Cheaters” (1947) portrayed the terrible consequences of greed and distrust as the bewitched spectacles of an infamous sorcerer are discovered hidden in the secret drawer of some antique furniture. The ancient eye glasses reveal the naked truth and soul of anyone encountered by the wearer, exposing in unimagined honesty, the inner thoughts and heart of their focus. Little is left to the imagination as, one by one, its victims wear the accursed “cheaters,” falling victim to dirty truths that might better have been left unspoken. As secrets unravel in unwitting candor, betrayal and revenge all but destroy the inquisitive inheritors of the deadly spectacles until, at last, the ugliness of one’s own soul drives the final owner to madness and suicide. As in Hitchcock’s cinematic morality play Rear Window (1954), there is little reward for even the most selfless peeping tom. Bloch’s characters draw noble, self serving parameters for themselves in which the hypocrisy of their mental eavesdropping achieves intellectual justification and moral outrage but, in the end, the lines between veracity and deception become as blurred as the distorted lens of the “cheaters.”

Most, if not all, of Bloch’s stories involve damaged people. They are misfits living beneath societal radar, outcasts from the mainstream living lives of quiet desperation. Some are overweight and slovenly, while others are isolated and lonely. They are abandoned by their world, left to find solace in unsavory redemption. There is little tolerance for the unattractive or unintelligent in a world of uniformity, and so these discarded souls must reach out in directions normally shunned by polite society. Abnormality attracts its own, and so humanity’s refuse finds value in the darker corridors of exploration. Bloch’s protagonists have degenerated to the deepest refuge of the inhuman psyche, finding comfort and delusional grandeur in satanic ritual and supernatural depravity. Their decadence offers respite from the outer storm of derision, and seeming unity in leprous colonization. Often, their rebellious rage threatens the very balance of sanity and reason, as miscreants and misfits discover validation in psychological deformity and demonic possession.

Bloch, like Lovecraft before him, was able to vividly illustrate a vast nether land in which deformity threatens to overcome the waking world, while night consumes the sun. Lovecraft’s terrifying Cthulhu Mythos found new, if fetid, breath in a continuing sequence of tales based upon the demented writings of the “Mad Arab,” Abdul Alhazred, in the fabled book of the damned, the “Necronomicon.” Anyone in possession of this hellish tome might summon the “great old ones” from their slumber, causing a tear in the fragile fabric of time and space in which the lumbering elder gods might rupture the Earth once more, achieving infinity in terrifying abandon. After Lovecraft’s death in 1937, Bloch expanded the mythological library of literature sought by sorcerers with such infamous texts as “De Vermis Mysteriis,” and “Cultes des Goules,” each offering unholy access to monstrous damnation.

In 1945, Bloch was asked to write exclusively for a new syndicated radio program called Stay Tuned For Terror. Broadcast and produced from Chicago, the series presented a full season of thirty-nine episodes showcasing the work of the author, which he adapted for air from his own short stories. In addition to writing for print and for radio, Bloch held down regular weekly employment as a copywriter for the Gustav Marx advertising agency, a position he maintained for eleven years.

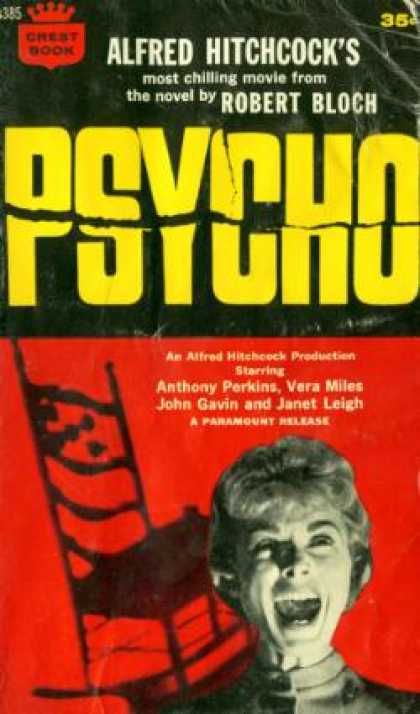

Although maintaining a respectable income and reputation during the forties and fifties, and winning the coveted Hugo for his short story “That Hellbound Train” (1958), Bloch continued to reside in the Midwest and worked in an advertising position in order to remain economically afloat. That changed in 1959 when the writer published his new novel…the story of a boy, his mom, and a motel. The work, which he titled “Psycho,” based somewhat loosely upon the real life exploits of notorious Wisconsin mass murderer Ed Gein (as was the somewhat less subtle Texas Chainsaw Massacre), changed Bloch’s life forever. The book was purchased by blind agents for Alfred Hitchcock and the rest, as they say, is history. Having literally no idea who was purchasing his book, Bloch sold the film rights for something in the neighborhood of two thousand dollars. Had the identity of the purchaser been revealed, the author might have been entitled to a far grander sum. While Outer Limits writer/producer Joseph Stefano penned the screenplay for the controversial motion picture, Hitchcock commented in print that “Psycho was ninety percent Robert Bloch’s book.”

Psycho will forever remain Robert Bloch’s most popular and identifiable work based largely, of course, upon the success and legacy of the motion picture. To begin with, Hitchcock was one of the most respected and enduring directors on the world stage, and so his decision to make a film of the author’s work was one of considerable importance to Bloch. Much has been said about the director’s decision to do away with the star of the picture roughly half way through the film, and how daring and provocative that remarkable creative decision actually was. To his credit, Hitchcock wisely chose a major actress to play the tragic Marion Crane, enabling her shocking early demise to attain near operatic surprise and dramatic crescendo. However, it must be remembered that Marion was killed quite early on in Bloch’s novel, as well, insuring calculated shock by the unprepared reader. Hitchcock merely embellished the calculation by casting the biggest star in the film as the doomed heroine.

Hitchcock’s other masterly decision was to cast Anthony Perkins in the role of Norman Bates. Unlike Bloch’s sleazier depiction of Norman, Hitchcock chose to portray Norman as the boy next door, an outwardly shy sexual innocent, brilliantly camouflaging his Jekyll and Hyde persona. Hence, the revelation of his inner demons became more effectively disturbing. In some ways, Norman Bates was a projection of Robert Bloch’s own literary personality. As stated earlier, Bloch was himself a gentle, sensitive soul with an appreciation for the arts, and a broad, infectious sense of humor. When he chose to don the cape of creativity, however, he transformed himself into a far darker, Freudian evocation of his personal complexity and shadowy identity. It may truthfully be stated that each of us masks our own inner demons with smiles and banal pleasantry. If Robert Bloch, during his waking hours, was his own Henry Jekyll then, surely, his Mr. Hyde would take center stage when immersed in the twilight zone inhabited by Norman Bates.

The genius of Bloch’s Psycho is, of course, that the supposed main character of the novel isn’t revealed as merely a “red herring” until well into the story’s progression. The groundwork for Marion Crane’s moral dilemma and near redemption is laid out meticulously. She has abandoned her integrity out of thoughtless greed, never fully comprehending the circumstances of her fall from grace or its ultimate consequence. She has been entrusted with depositing forty thousand dollars by her boss and his client, deciding instead to steal the money and join her lover in an idealized dream of financial security and sexual domesticity. The reader’s concern, then, is that she has come to her senses in time to redeem her fortunes and return to her life, virtually unscathed by a momentary decline into criminality. It is only then that we learn that the story isn’t about Marion Crane at all but, rather, a recently introduced proprietor of a seedy motel in which she quite innocently decides to spend the night, while en route to her destiny. Tragically, the motel IS her destiny as she is gruesomely slaughtered by Norman Bates, the true focus of the novel. All that has transpired up to this point is merely the expository groundwork that serves to introduce the reader to the real thrust of both the story, and Norman’s knife. Marion is expendable. She is a fragile, flawed individual who can be sacrificed for the greater good of the novel. Bloch has carefully led the reader into a sheltered sense of complacency, travelling down a calculated detour to a climactic intersection in which the proverbial rug is unceremoniously pulled out from under him. Marion’s world, as well as our own, has been turned inside and out. The bathroom door has closed, and there is no turning back.

On the basis of the novel’s huge success, Bloch moved his family to Los Angeles, leaving his day job behind and settling into the film community as a full time, working author. Any acrimony with Hitchcock was washed away by the muddy waters of success, and the opportunity to write stories for the director’s popular television series, Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Bloch became one of the program’s most prolific writers, contributing some seventeen teleplays including “The Greatest Monster Of Them All” (1961), “The Sorcerer’s Apprentice” (1962), and “The Sign Of Satan” (1964) guest starring Christopher Lee.

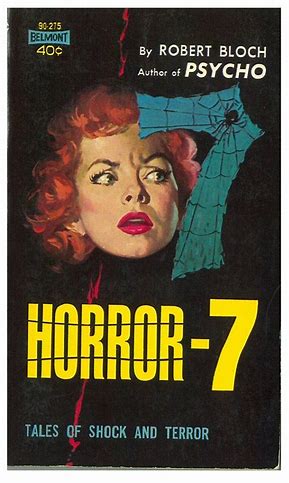

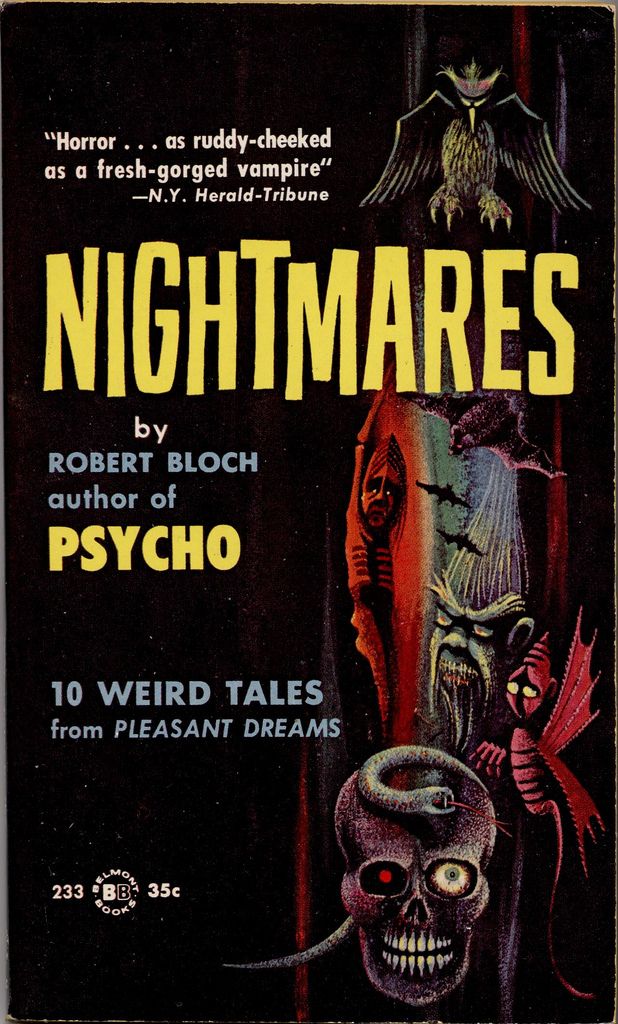

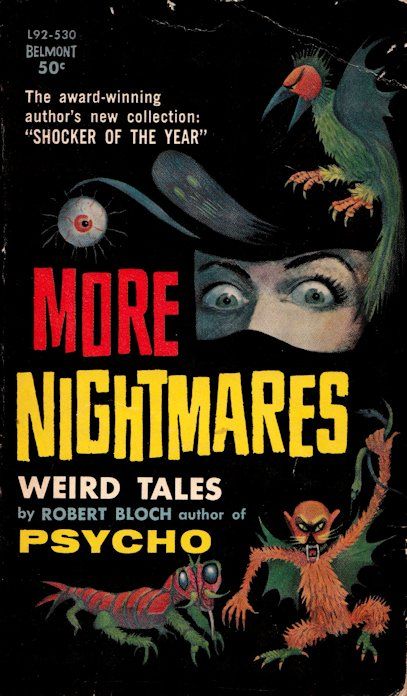

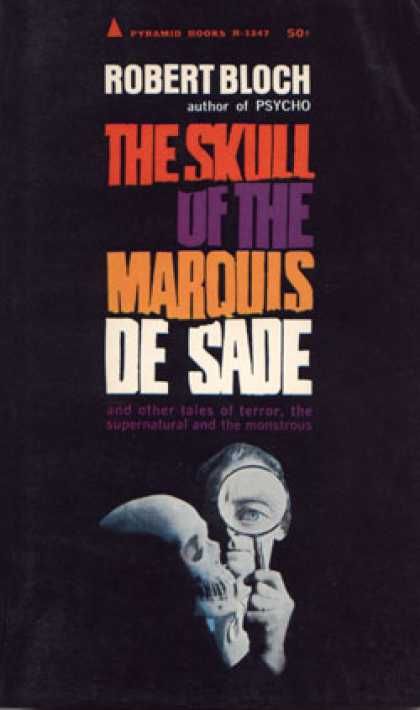

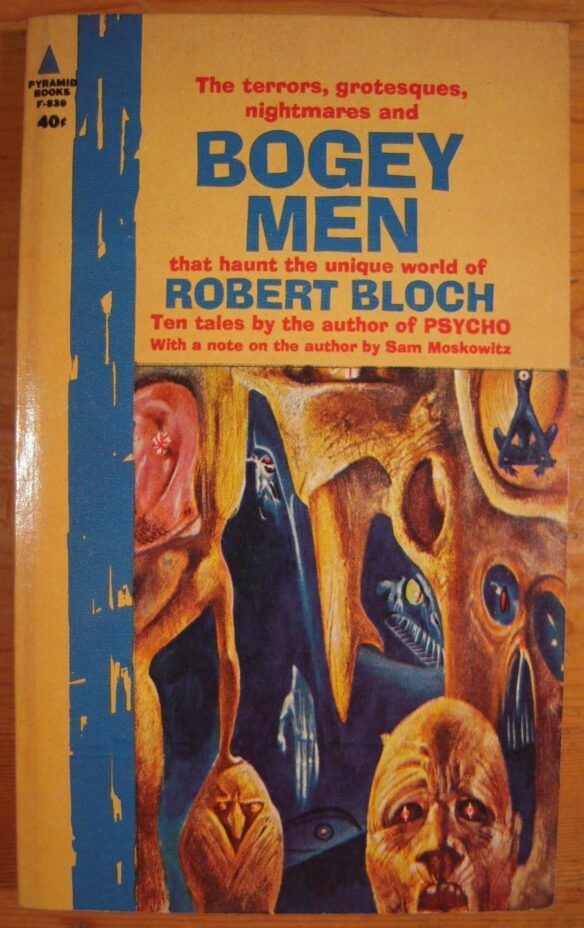

Collections of short stories by the celebrated writer began appearing both in hard and paperback editions with luridly commercial titles such as Nightmares, More Nightmares, Even More Nightmares, Pleasant Dreams, Mysteries of the Worm, and Yours Truly, Jack The Ripper.

It was about this time that NBC television producer, Hubbell Robinson, began developing a new series for the network to star horror actor Boris Karloff. Airing over the network in prime time from 1960 until 1962, Boris Karloff’s Thriller remains the most frightening, potent and atmospheric series in the troubled history of horror television. The series presented some of the most disturbing and nightmarishly visual hours of the past fifty years and many of its most memorable, haunting episodes were written for the program by Robert Bloch. These included “The Cheaters” (the story of a deadly pair of Victorian spectacles that delved into the truth of every soul it perceived), “The Grim Reaper” (featuring young William Shatner as the greedy heir to a writer’s fortune who conspires to frighten the elderly woman to death with stories of a terrible painting coming to life) and, perhaps, the program’s defining moment. Based upon Bloch’s short story, “The Hungry House,” William Shatner was featured once again in “The Hungry Glass” as a recovering victim of a nervous breakdown who purchases a house with a terrible secret, and strangely devoid of any mirrors. Rarely has the medium of film so chillingly captured the gothic temperament and nightmarish language of horror as effectively, or as reverently, as in this uncompromisingly graphic, black and white television series. If Psycho brought Robert Bloch’s name and reputation into the cinematic consciousness of theater goers, Boris Karloff’s Thriller brought the author lasting fame and recognition in captive living rooms across the country. It was fitting, then, that the decadent domicile used by NBC and Universal for the “Hungry Glass” episode was, in fact, the very same structure utilized by Hitchcock to house Norman Bates and his skeletal mother. Despite the apparent popularity and success of the literate young series, however, it was surprisingly cancelled by the network after only two years, reportedly at the urging of Alfred Hitchcock who felt that its early suspense oriented stories constituted direct competition to his own half hour anthology program on NBC.

Assignments for both television and theaters continued with screenplays for The Cabinet Of Caligari (1962), “The Couch” (1962), Strait-Jacket (1964) (starring Joan Crawford as an ax murderess), The Night Walker (with the former husband and wife team of Barbara Stanwyck and Robert Taylor in 1964) The Skull (1965) with Peter Cushing (adapted from Bloch’s short story, “The Skull Of The Marquis De Sade”) (1966), The Psychopath (1966), Torture Garden (1967), The Deadly Bees (1967), The House That Dripped Blood (1971), Asylum (1972) (once again starring Peter Cushing), The Cat Creature (1973) for ABC television, three episodes of the original Star Trek (“What Are Little Girls Made Of,” “Wolf In The Fold,” and “Catspaw”). Star Trek’s “Wolf In The Fold” offered a futuristic variation of his earlier take on the White Chapel slasher, “Yours Truly Jack The Ripper.” Bloch had been working on a massive teleplay for CBS television in 1980, an adaptation of H.G. Wells’ “In The Days of the Comet” produced by the legendary George Pal, when the fantasy film pioneer died of a sudden heart attack. The ambitious collaboration, sadly, was not to be. Among Bloch’s most curious projects for television aired as the final episode of the ABC series, Bus Stop. Based upon the popular 20th Century Fox classic starring Marilyn Monroe, this all out horror tale became the final episode of the short lived series, with actor Alfred Ryder in a frightening adaptation of Bloch’s short story, “I Kiss Your Shadow.”

Bloch was never entirely satisfied with his screen work, for neither the direction or the theatricality of these final picturizations ever truly captured the genuine dread portrayed by his written word. Only Hitchcock’s Psycho ever realized the black and white simplicity of the writer’s psychology of horror. Bloch wrote in black and white or, to put it more succinctly, from a darkened perspective devoid of color. The visualization of horror must be stripped of comfort with the familiar. While colors enrich the waking realm in which we work and interact, their very reassurance serves to erase the frighteningly primordial recollection of a world immersed in dreams. Bloch’s stories were essentially driven by his, and our, deepest fears. As we struggle to awaken from night’s journey through shadows, it is the first light of day in which we must find solace. Bloch understood that nightmares are derived from darkness, for it is there that familiarity is lost. One cannot understand what he cannot see. Rationalization is clarified by light. We can attempt to define what lies before us. It has definition and color. Strip away that color, however, and the horizons before us become dreamlike, or surreal. Drained of color, the world degenerates into a simplistic panorama in which monstrous apparitions can co-exist comfortably with reality. It is here, in a world stripped of pretense and calming reassurance, that we walk naked through the night. Alone in the darkness, we become vulnerable to emotional assault, and prey to the denizens of darkness. The simplicity of black and white has now prepared our emergence, or descent, into the nether world of dreams and nightmares. It is for this reason, perhaps, that Bloch’s most successful work on screen remains the quintessential horror anthology hosted by Boris Karloff for NBC Television.

Bloch lent distinction to his name whether adapting one of his own short stories for the screen, or reworking the efforts of another writer. Asked to adapt a short story written by Harold Lawlor for the Thriller series, the author composed one of his most terrifying confections, entirely re-structuring the thread of the original tale and turning it into modern horror classic. “The Grim Reaper” aired during the 1961 television season, becoming one of the earliest efforts in the fledgling series’ subtle transformation from suspense to outright horror. The greedy nephew of an Agatha Christie styled mystery writer attempts to frighten his wealthy aunt to death with the gift of an accursed portrait of a skeletal avenger brandishing a razor like scythe. The tale is, of course, a lurid fabrication concocted by Paul Graves (William Shatner) to drive his elderly aunt either to madness or to death so that he might inherit her fortune. His plan works all too well, for the normally grounded writer (Natalie Schafer) sits before the awful portrait, drinking herself into an hallucinatory stupor in which she imagines that the evil figure in the picture has stepped down from its bloody perch to stalk her. The alcohol induced delusion convinces her that Paul’s wicked stories of a cursed creature are, indeed, true and she succumbs to the sum of her fears while frightened to death. Paul has woven his insidious tale a little too well, however, for as he prepares his departure from the house, he senses something not quite right about the portrait. The hideous image upon the bloody canvas has disappeared from its ornate frame. As Paul clutches the opening of his mouth in mortal fear, barely stifling a heart shattering gasp, he hears the rhythmic swish of the deadly blade from somewhere in the room. Nothing is seen but Paul’s mask of terror as the sounds grow closer to his body, frozen in paralyzing fear. An awful scream is heard from beyond the locked door to the library, as frantic relatives and friends of the late writer try unsuccessfully to pry open the lock. Paul’s own vivid imagination has conspired to consume his weak and greedy psyche, and he is torn to shreds by the monstrous aberration he conceived. The Reaper has returned to its menacing lair within the canvas as though it had never left its position on the wall…and yet…there is fresh blood glistening on the painted scythe.

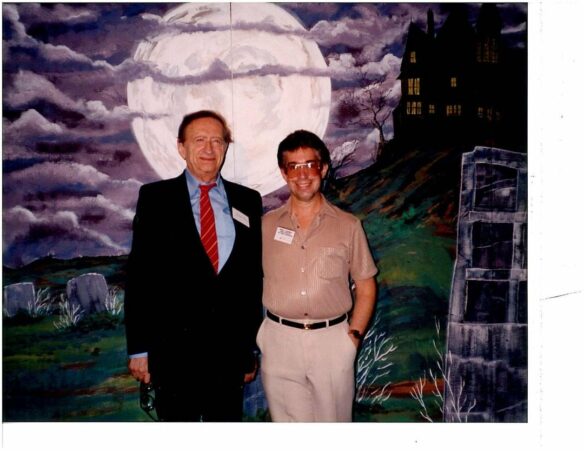

Both honored and treasured in his later years, Bloch received a Life Achievement Award at the first World Fantasy Convention in 1975, a Big Heart Award presented at the World Science Fiction Convention, the Bram Stoker Life Achievement Award, and the World Horror Convention’s “Grand Master Award.” A respected and gifted writer of mystery, as well as horror fiction, he served a term as President of The Mystery Writers Of America. During his lifetime, Bloch wrote twenty-five novels, four hundred short stories, an infinite number of collections, radio programs, screenplays and teleplays.

In his personal life, despite his public persona, Robert Bloch was a quiet, gentle man with a robust, self-effacing sense of humor and a love of the arts. Cancer consumed his sensitive soul in 1994 at age 77. The Grim Reaper of his imagination had returned to claim just one more victim, as endless night descended in Pleasant Dreams.

++ Steve Vertlieb, 2008

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts to your email.

His urn is in the shape of a book and is just a few steps from Ray Bradbury, his longtime friend.

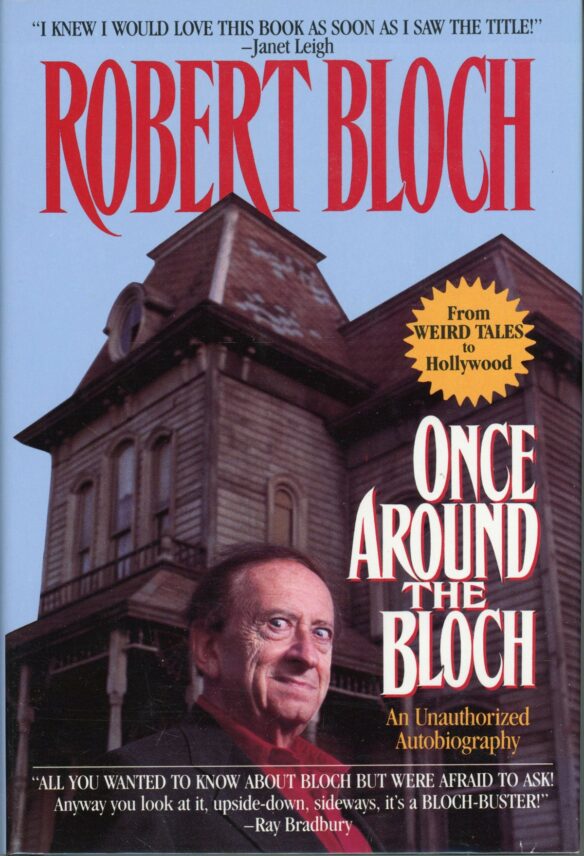

As Hugo Administrator, I had the privilege of phoning Robert Bloch in 1994 to let him know that his memoir Once Around the Bloch was a Hugo finalist for Best Nonfiction Book (as the category was called then).

“How do you know it’s nonfiction?” cracked Bloch.

“Well, sir, that’s what the voters nominated it as,” was all I could say.

A good summary of Bloch’s professional writing career. But more significant to me than all his fiction, Bloch was one of the greatest (if not the greatest) fannish science fiction fan in history. This book, which I purchased from Earl Kemp at Discon I back in 1963, changed the entire course of the rest of my life:

https://books.google.com/books/about/The_Eighth_Stage_of_Fandom.html?id=PFILAAAACAAJ

There are still reasonably cheap copies of the first edition from Earl’s Advent Press to be found on eBAY. https://tinyurl.com/3yppsxja

Goodness, an essay of this length without one mention of Bloch’s humorous work? Lefty Feep, at least, is worth a mention….

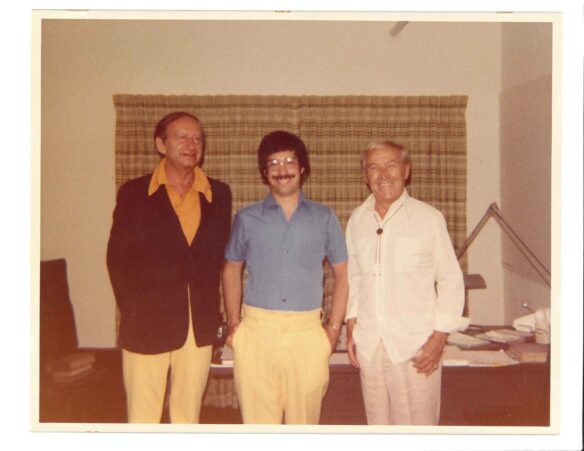

Bob Bloch and Bob Tucker were good friends; I met and got to know Bloch at Tucker’s house when he visited the Tuckers back in the ’70s and ’80s. He was indeed a remarkable and delightful fellow and a great writer. Unfortunately, I didn’t take the opportunity to ask Bloch if he had ever seen the motel in the village of Bates on the old road between Springfield, Illinois, where I live, and Jacksonville, Illinois, where Tucker lived at the time. Alas! by the early ’90s, the Bates Motel there was in ruins–the new Interstate took almost all the traffic off the old road–and it was eventually torn down.

http://file770.com/robert-bloch-the-clown-at-midnight-2/

ROBERT BLOCH: “THE CLOWN AT MIDNIGHT”

Perhaps Alfred Hitchcock’s most famous, and enduringly popular motion picture, was his celebrated 1960 production of “Psycho,” screening this evening on Turner Classic Movies, and based upon the novel by frequent Hitchcock television collaborator, Robert Bloch.

Robert Bloch has at last been inducted into the Rondo Awards “Monster Kid” Hall of Fame for his lifetime of literary achievements. Born April 5th, 1917, Robert Bloch would have been 106 years old. His contributions to literature, film, television, and popular culture are incalculable.

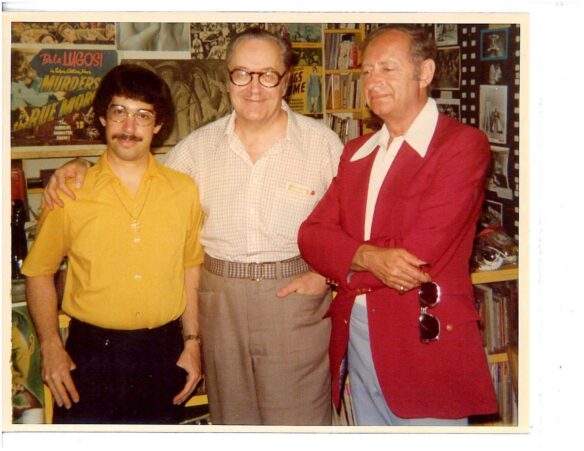

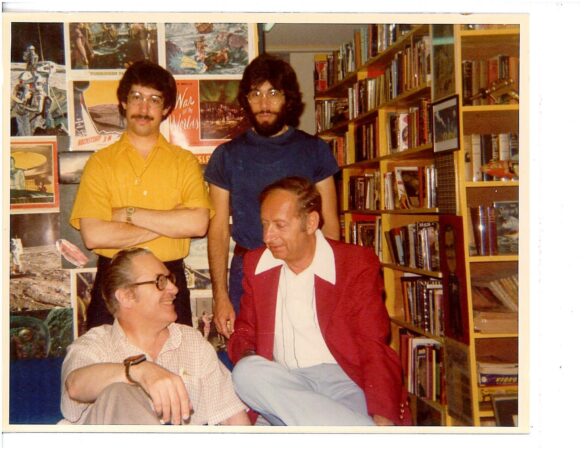

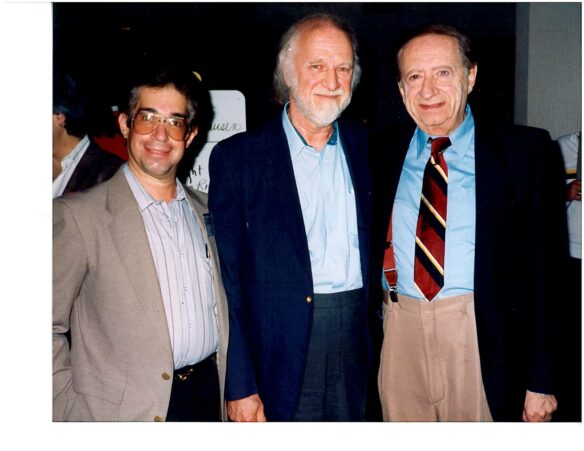

This is the story of my twenty-five year friendship with acclaimed writer Robert Bloch, the author of “PSYCHO.” It is a published, Rondo Award nominated remembrance of a complex, remarkable man, and our affectionate relationship over a quarter century.

Robert Bloch was one of the founding fathers of classic horror, fantasy, and science fiction whose prolific prose thrilled and influenced the popular genre, its writers, and readers, for much of the twentieth century. An early member of “The Lovecraft Circle,” a group of both aspiring and established writers of “Weird Fiction” assembled by Howard Phillips Lovecraft during the early 1930’s, Bloch became one of the most celebrated authors of that popular literary genre during the 1940’s, 1950’s, and 1960’s, culminating in the publication of his controversial novel concerning a boy, his mother, and a particularly seedy motel.

When Alfred Hitchcock purchased his novel and released “Psycho” with Anthony Perkins and Janet Leigh in 1960, Bloch became one of the most sought after authors and screen writers in Hollywood. His numerous contributions to the acclaimed television anthology series “Alfred Hitchcock Presents” are among the best of the director’s classic suspense series, while his legendary scripts, adaptations and teleplays for Boris Karloff’s “Thriller” series for NBC are among the most bone chilling, frightening, and horrifying screen presentations in television history.

He also famously penned several classic episodes of NBC’s original “Star Trek” series for producer Gene Roddenberry. Writers Stephen King, Richard Matheson, and Harlan Ellison have written lovingly and profusely of their own literary debt to Robert Bloch. Bob was, for me, even more significantly, a profoundly singular mentor and cherished personal friend for a quarter century. This is the story of that unforgettable relationship.

http://file770.com/robert-bloch-the-clown-at-midnight-2/

Steve Vertlieb

According to Bloch’s 1994 autobiography, Bloch and his agent sold the film rights to Psycho for $9500.

Those rights included sequel rights, a rarity at the time. In the 1980s when plans for a sequel were announced, Bloch had forgotten that the old contract included them because he was opposed to a sequel. I asked him at the time what he thought of them making a movie sequel and he vowed that “this will happen over my dead body!” But it did happen, over and over again. His own novel Psycho II killed off Norman Bates. At the Harlan Ellison Roast in the 1980s, after everyone made jokes about Harlan, Harlan made jokes about his friends, remarking that Anthony Perkins now had a second career making sequels to Psycho. Bloch was on the stage and he looked like he’d bitten into a lemon as this was clearly a sore point with him.