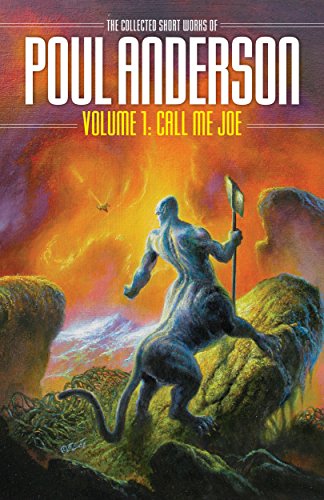

By Paul Weimer: Call Me Joe by Poul Anderson strongly starts off a NESFA Press series of volumes covering the work of one of the key 20th century writers of Science Fiction, Poul Anderson

In the introduction, the editor, Rick Katze, states “This is the first in a multi-volume collection of Poul Anderson stories. The stories are not in any discernible pattern”. The pieces of fiction are an eclectic mix of early works in his oeuvre, mixed with poetry and verse that range across his entire career.

The contents include:

- Call Me Joe

- Prayer in War

- Tomorrow’s Children

- Kinnison’s Band

- The Helping Hand

- Wildcat

- Clausius’ Chaos

- Journey’s End

- Heinlein’s Stories

- Logic

- Time Patrol

- The First Love

- The Double-Dyed Villains

- To a Tavern Wench

- The Immortal Game

- Upon the Occasion of Being Asked to Argue That Love and Marriage are Incompatible

- Backwardness

- Haiku

- Genius

- There Will Be Other Times

- The Live Coward

- Ballade of an Artificial Satellite

- Time Lag

- The Man Who Came Early

- Autumn

- Turning Point

- Honesty

- The Alien Enemy

- Eventide

- Enough Rope

- The Sharing of Flesh

- Barbarous Allen

- Welcome

- Flight to Forever

- Sea Burial

- Barnacle Bull

- To Jack Williamson

- Time Heals

- MacCannon

- The Martian Crown Jewels

- Then Death Will Come

- Prophecy

- Einstein’s Distress

- Kings Who Die

- Ochlan

- Starfog

The introduction is not quite correct, in that the reader can find resonances between stories, sometimes in stories back-to-back. There are plenty of threads, and a fan of Anderson and his Nordic viewpoint might call it a skein, a tangled skein of fictional ideas, themes, ideas and characters. The same introduction notes that a lot of the furniture of science fiction can be found in early forms here, as Anderson being one of those authors who have made them what they were for successive writers. In many cases, then, it is not the freshness of the ideas that one reads these stories for, but the deep writing, themes, characters and language that put Anderson in a class of his own.

The titular story, for example, “Call Me Joe,” leads off the volume. It is a story of virtual reality in one of its earliest forms, about Man trying to reach and be part of a world he cannot otherwise interact with. Watchers of the movie Avatar will be immediately struck by the story and how much that movie relies on this story’s core assumptions and ideas. But the story is much more than the ideas. It’s about the poetry of Anderson’s writing. His main character, Anglesey, is physically challenged (sound familiar). But as a pseudojovian, he doesn’t have to be and he can experience a world unlike any on Earth:

Anglesey’s tone grew remote, as if he spoke to himself. “Imagine walking under a glowing violet sky, where great flashing clouds sweep the earth with shadow and rain strides beneath them. Imagine walking on the slopes of a mountain like polished metal, with a clean red flame exploding above you and thunder laughing in the ground. Imagine a cool wild stream, and low trees with dark coppery flowers, and a waterfall—methanefall, whatever you like—leaping off a cliff, and the strong live wind shakes its mane full of rainbows! Imagine a whole forest, dark and breathing, and here and there you glimpse a pale-red wavering will-o’-the-wisp, which is the life radiation of some fleet, shy animal, and…and…”

Anglesey croaked into silence. He stared down at his clenched fists then he closed his eyes tight and tears ran out between the lids, “Imagine being strong!”

Reader, I was moved.

That’s only part of the genius of Anderson’s work shown here. Anderson has many strings in his harp and this volume plays many of those chords.

There is the strong, dark tragedy of “The Man Who Came Early” which is in genre conversation with L Sprague De Camp’s “Lest Darkness Fall” and shows an American solider, circa 1943, thrown back to 11th century Iceland and, pace Martin Padway, doing rather badly in the Dark Ages. Poul Anderson is much better known for his future history that runs from the Polesotechnic League on through the Galactic Empire of Dominic Flandry, but this volume has three stories of his OTHER future galactic civilization, where Wing Alak manages a much looser and less restrictive galactic polity, dealing with bellicose problems by rather clever and indirect means.

And then there are his time travel tales. “Time Patrol” introduces us to the entire Time Patrol cycle and Manse Everard’s first mission. I’ve read plenty of his stories over the years, but this first outing had escaped me, so it was a real delight to see “where it all began”. “Wildcat” has oil drillers in the Cretaceous and a slowly unfolding mystery that leads to a sting in the tail about the fragility of their society. And then there is one of my favorite Poul Anderson stories, period, the poetic and tragic and moving “Flight to Forever”, with a one-way trip to the future, with highs, lows, tragedies, loss and a sweeping look at man’s future. It still moves me.

And space. Of course we go to space. From the relativistic invasion of “Time-Lag” to the far future of “Starfog” and “The Sharing of Flesh,” Anderson was laying down his ideas on space opera and space adventure here in these early stories that still hold up today. “Time-Lag’s” slow burn of a captive who works to save her planet through cycles of invasion and attack, through the ultimate tragedy of “Starfog” as lost explorers from a far flung colony seek their home, to the “Sharing of Flesh,” which makes a strong point about assumptions in local cultures, and provides an anthropological mystery in the bargain. “Kings Who Die” is an interesting bit of cat and mouse with a lot of double-dealing espionage with a prisoner aboard a spacecraft.

Finally, I had known that Anderson was strongly into verse and poetry for years, but really had never encountered it in situ. This volume corrects that gap in my reading, with a variety of verse that is at turns, moving, poetic, and sometimes extremely funny. The placing of these bits of verse between the prose stories makes for excellent palette cleansers to not only show the range of Anderson’s work, but also clear the decks for the next story.

The last thing I should make clear for readers who might be wondering if this volume truly is for them to is to go back to the beginning of this piece. This volume, and its subsequent volumes, are not a single or even multivolume “best of Poul Anderson”. This is a book, first in a series, that is meant to be a comprehensive collection of Poul Anderson. This is not the book or even a series to pick up if you just want the best of the best of a seminal writer of 20th century science fiction. This volume (and I strongly suspect the subsequent ones) is the volume you want if you want to start a deep dive into his works in all their myriad and many forms. There is a fair amount from the end of the Pulp Era here, and for me it was not all of the same quality. I think all of the stories are worthy but some show they are early in his career, and his craft does and will improve from this point. While for me stories like the titular “Call Me Joe”, “Flight to Forever”, “The Man Who Came Early”, and the devastating “Prophecy” are among my favorite Poul Anderson stories, the very best of Poul Anderson is yet to come.

Discover more from File 770

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

A Time Patrol story I haven’t read. Cool!

“Journey’s End” should be “Journeys End” – Anderson took the title from a Shakespeare line, “Journeys end in lovers’ meeting – / Every wise man’s son doth know”.

Raskos: “Journey’s End” should be “Journeys End”

Quite likely, however, when you look at the publication history of the story on ISFDB you find that it was first published in F&SF as “Journeys End,” but when it was collected in The Best from Fantasy and Science Fiction, Seventh Series (1958) by Anthony Boucher, the title was “Journey’s End,” and that version was repeated in Robert Silverberg’s anthology Dark Stars (1969).

But there are distinguished editors on the other side — probably more. It was spelled “Journeys End” in Damon Knight’s A Science Fiction Argosy (1972) and DAW’s Book of Poul Anderson (1975) and many other places.

I will say the NESFA Press edition here uses the “Journey’s End” spelling, just to reassure you that’s not merely another of my typos.

It never occurred to me that you might have blooped it, Mike – I’ve seen it published as both, but I believe that Anderson himself pointed out somewhere what the correct form is.

I always liked the story, downer though it is, so the matter stuck in my mind.

/pedantry