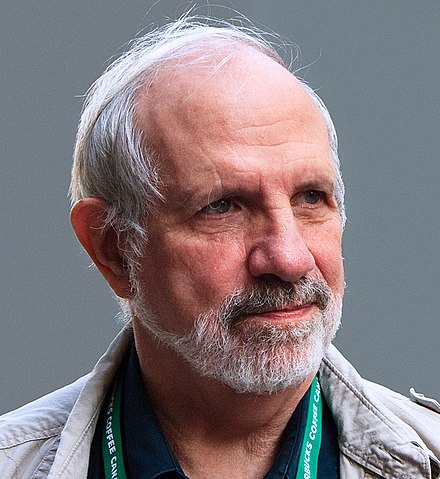

By Steve Vertlieb: The irony of Brian DePalma’s seeming obsession with mayhem and graphic bloodletting is that the director is essentially a humanist. Throughout his work on the screen, there is a thread of humanity in search of acceptance. Unlike the Hitchcockian twists of plot with which his work has most frequently been compared, DePalma’s heroes and heroines are essentially lost and lonely victims of their own sordid self-destructiveness.

In DePalma’s nightmare world, violence and brutality are merely the window-dressing on a canvas of frustration and bitterness. The landscape of his vision perversely masks the tragic isolation of small, lonely people willingly imprisoned within the boundaries of their own psychological exile. Misfits and outcasts, DePalma’s characters watch life from the sidelines, experiencing joy only in the limited reality of those whose perception and awareness are themselves blighted and unimaginative.

These hapless marionettes struggle exhaustively to free themselves from the invisible bonds that tie them to irreversible tragedy. In the agony of their loneliness, they strike out passionately, inflicting a mirror image of their own grief upon whomever they perceive as causing their containment. They are incapable of penetrating the outer wall of their prison or of comprehending the nature of the puppeteer whose whims and fancies manipulate the strings to which they are irrevocably tied. For it is the director whose prejudicial conceptions of mediocre existence guide their fate to its ultimate and tragic conclusion. It is DePalma’s own sense of hopelessness and human suffering that sadly dooms the characters of his design.

For his emergence into the suspense/horror genre, DePalma chose as the vehicle a bizarre tale of sibling rivalry entitled Sisters. Like Hitchcock, DePalma chose the imaginatively visual theater of the fanciful with which to perfect his creative yearnings. Working within the limitless confines of a genre whose very nature encouraged the freedom of creative experimentation, DePalma began to explore the terrain of his own developing artistic maturity. In seeking to enhance his style and storytelling technique, he chose the most expressive of styles, the media offering the most exciting challenges to a young, gifted film stylist.

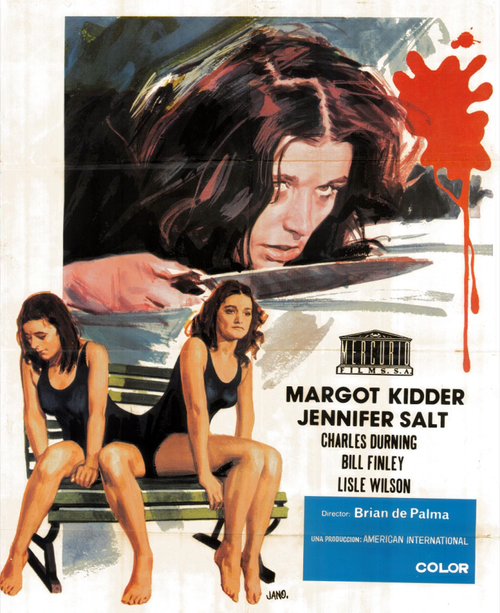

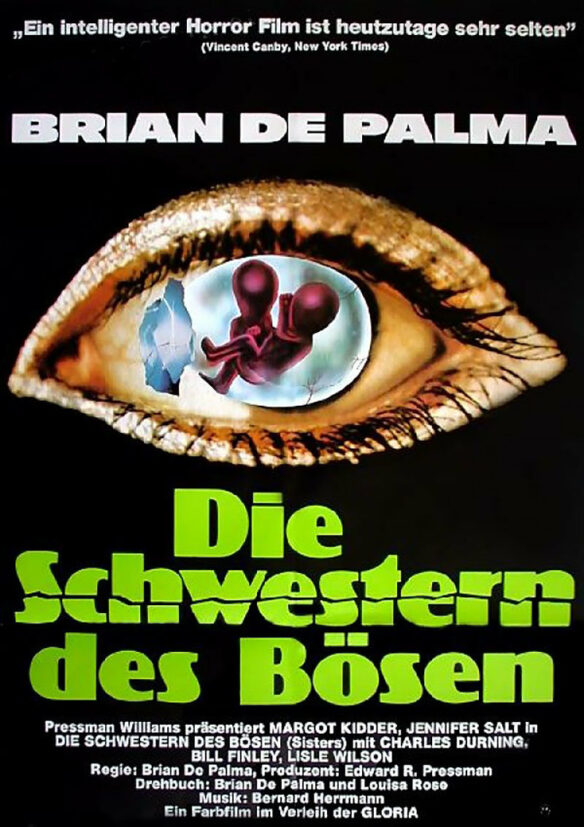

Released through American International Pictures in 1973, Sisters concerns the strange relationship of Danielle and Dominique, twin sisters whose disturbing affinity for one another seems to surpass normal familial affection. The film begins as Danielle, a French-Canadian model, is observed disrobing by Phillip Woode, a young newspaperman. As the action stops and lurid titles flash upon the screen, it immediately becomes apparent that we are watching a television game show entitled “Peeping Toms” in which the contestants are judged by the degree of their voyeurism. Woode (Lisle Wilson) invites Danielle to dinner after the show. During dinner they are disturbed by Emil Breton (Bill Finley) whom Danielle identifies as her former husband.

Danielle invites Woode back to her apartment where they make love. In the morning, Phillip awakens to the sound of offscreen voices arguing in French. Dominique has visited her sister on the pair’s birthday but is apparently angered over the appear ance of an intruder in Danielle’s bed. Danielle sends Phillip out on an errand to renew her medicine which is running low. While on his errand, Phillip decides to make peace between the twins by buying a birthday cake. Returning to the apartment, Phillip approaches the sleeping body of a girl he presumes to be his lover. Reaching for the knife on the cake plate, the girl plunges the blade into Phillip’s body, stabbing him repeatedly until the reporter’s lifeless form collapses on the floor.

The murder is witnessed by Grace Collier (Jennifer Salt), another reporter whose apartment overlooks Danielle’s. When Danielle returns to the apartment, she realizes that Dominique has murdered her lover in a jealous rage. With Emil, who has now arrived at the scene, the pair attempts to hide the body of the slain journalist and protect the missing sister.

In the classic Hitchcock mold, Grace tries to convince the police that she has witnessed a murder. Since Grace has authored a series of articles on the police entitled “Why we call them pigs,” however, the officers investigating the case are rather reluctant to cooperate with her. It remains for the reporter to hire a private investigator (Charles Durning) who, with the determined witness, sets out to unravel the mystery. They discover that Danielle and Dominique were celebrated Siamese twins, separated as children. According to a Life magazine journalist who covered their story, however, Dominique died during the fateful operation, and only Danielle survived. It soon becomes clear that like Norman Bates in Hitchcock’s Psycho, Danielle Breton conceals a split personality, harboring an unbearable sense of guilt for the death of her sister and assuming both roles, thus negating the death. When Phillip entered Danielle’s life, Dominique flew into a jealous rage. In the battle for affection between the two struggling personalities, Dominique emerged the winner, and Phillip was made to pay a handsome price for his interference.

Danielle is a murderess, certainly, but, as played by Margot Kidder, a gifted and beautiful actress, she is a tragic doomed heroine. Danielle believes that her sister survived the operation. There is a horrible nobility in the efforts of the surviving sister to protect her sibling, not realizing that it is she herself who has committed a gruesome murder. Danielle is a helpless innocent, struggling valiantly to retain a sense of human dignity but devoured unknowingly by forces wholly beyond her awareness or control. Danielle is doomed from the start. She fights in the only world her consciousness will permit, but it is that very limited consciousness which will lead to her eventual demise.

Gaston Leroux’s The Phantom of the Opera was to provide the inspiration for Brian DePalma’s next work. Phantom of the Paradise, released by Twentieth Century-Fox in 1974, was a tragicornic satire rooted in the hereditary insanity of both horror films and rock and roll. Phantom of the Paradise is a mad, manic exercise in black comedy highlighted by Paul Williams’s demonic performance as the satanic dwarf Swan, a diabolical munchkin whose recording empire was derived when “He sold his soul for rock and roll.”

William Finley (Emil Breton in Sisters) is the sensitive young rock composer whose cantata is first coveted, then stolen, by the evil rock entrepreneur. Swan adopts the music of the young composer, Winslow Leach, as his own and plans to premiere the work at the opening of his new theater, The Paradise. Following. the story line of the Claude Rains (1943) and Herbert Lom (1962) versions of the classic horror tale, Leach invades the sanctuary of the evil impresario in order to retrieve his missing manuscript. Within the walls of Swan’s recording plant, Winslow tries to sabotage the machinery but instead finds his head caught in a record-pressing machine and horribly disfigured. This is the ultimate irony. The budding composer sees not his record pressed, but his head.

Adding insult to injury, Leach is shot by a security guard, escapes, but is presumed by all to be dead. Fate leads, however, to the new Paradise Theatre where the spectral presence of a phantom continues to sabotage plans for a gala rock opening. From a vantage point, hidden high in the rafters of the theater, Winslow observes the auditions for the premiere of Swan’s stolen rock cantata. The composer is taken with the lovely voice and gentle beauty of one of the singers, Phoenix (Jessica Harper), and conspires to blackmail Swan into casting the girl in the lead performance. Winslow worships Phoenix from afar, guiding her career anonymously and falling ever more deeply in love with her. Swan’s sadism continues unabated as he seduces Phoenix, knowing full well that Winslow is observing the pair through a rooftop skylight. His body and emotions terribly scarred, part of a world of ugliness whose jagged boundaries can never touch the sweet innocence of the girl he loves, Winslow screams in terrible anguish at the betrayal of love and beauty beneath the window. The awful fury of a raging storm blends its anguish with the primal agony of the captive phantom, tied by morbid fascination to endure his grief, unable to look away from a sight that mocks his soul.

Although Phantom of the Paradise is a brilliant, fiendishly funny satirical gem, there are moments of great poignancy. Phantom is comedy, to be sure, but despite its moments of hilarity, William Finley’s characterization of the beleaguered composer Winslow Leach falls well within the guidelines of DePalma’s doomed protagonist. Leach never has a chance to achieve the richness of life he quietly desires. Fame and financial success are robbed from him early in the scenario. Physical well—being is denied him when he loses his teeth during imprisonment inside the walls of a penitentiary, courtesy of the malevolent Swan. Finally, the love and tenderness of the woman he worships are forever denied him because of his ghastly appearance. Yes, even his once-handsome features have been decayed and corrupted by the clutches of a jaws-like record press intent on putting wax into his ears, rather than taking it out. Is it any wonder that Leach, the sensitive, artistic soul, becomes Leach, the revenge-thirsty Phantom of the Paradise?

The characters who populate DePalma’s scenarios are each, in their own way, smalltime losers. Their universe is a bleak, dreary ghetto wherein the inhabitants never seem to rise above the stench of despair. Survival is everything, and yet it seems the rarest commodity of all.

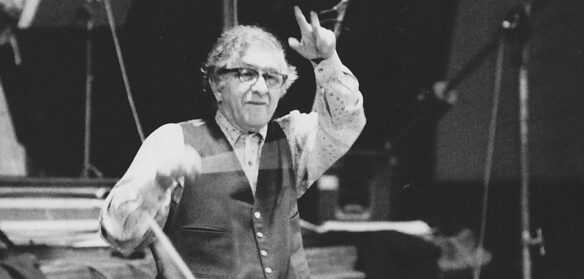

Survival in motion pictures may also have seemed a rather rare commodity to a young, struggling director searching for his roots. Sisters in 1973 was designed by its director as a deliberate imitation of the acknowledged master of suspense, Alfred Hitchcock, replete with all of Hitchcock’s traditional trappings, including a moody, bizarre musical score by Bernard Herrmann. If Sisters was a trifle rough around the edges, an imperfect salute from a technician largely inexperienced in the genre, then Obsession in I976 was a finely honed tribute from one artist to another.

In his attempt to recreate the experience of Hitchcock’s masterpiece Vertigo (Paramount, 1958), DePalma was inspired to create his own masterwork. Greatness rarely begets anything other than flattering imitations. Obsession was, however, an entirely different matter, for with this strange, haunting film, Brian DePalma achieved his own distinctly original claim to cinema posterity. With its painful, romantic imagery so delicately painted by Vilmos Zsigmond’s classical cinematography, its brilliant and complex screenplay composed by the powerful hand of writer Paul Schrader, its exquisitely ethereal, nearly overpoweringly beautiful musical score by Bernard Herrmann, the rnost provocatively gifted composer of Twentieth-century dramatic scoring, and the assured, spell-binding direction of an astonishingly talented director, Brian DePalma, Obsession seemed to equal the acclaimed magical mystery of the film it once aspired to impersonate.

Released through Columbia Pictures, Obsession weaves an intricate, fascinating tale of kidnapping, revenge, and obsessive love. On the tenth anniversary of their marriage, Michael and Elizabeth Courtland host a celebration attended by friends and associates. At evening’s end, the happy couple prepares to retire. Elizabeth leaves Michael briefly to check on their nine-year-old daughter Amy. When she fails to return, Michael (Cliff Robertson) goes searching for her and finds a note pinned to the bed which reads: “Do not call police. Be at home with $500,000 cash tomorrow if you want wife and daughter returned alive.” Turning to his partner Robert LaSalle (]ohn Lithgow) for help, Courtland raises the money but, despite the warning, notifies the police. The kidnappers are located, and a frantic chase by car ensues. In the pursuit, the escaping vehicle is destroyed, killing both Elizabeth Courtland and young Amy.

Years pass, and Michael Courtland, despite a halfhearted attempt at retaining his business affiliations, remains a broken man living in the ominous shadow of his tragic past. On a business trip with his partner to Florence, Italy, Courtland is encouraged to visit the legendary Church of San Miniato. There he observes a young woman restoring a priceless painting. As he catches sight of her, the world seems to stop, for she is the very image of his beloved Elizabeth.

Michael becomes obsessed and enchanted with the wonder of his second chance. He must win the love of his reincarnated wife, Sandra Portinari (Genevieve Bujold in both roles), and take her to their New Orleans home once again. Miraculously she agrees to marry him and returns to the home he shared with Elizabeth.

Michael is reborn. The scars and the awful pain disappear seemingly overnight along with the torturous deprivation that turned a loving, fulfilled human being into an emotionless shell. Shadows soon form, however, as Sandra herself feels a growing obsession for the portrait, clothing, and possessions of the dead Elizabeth. The young girl seems to lose herself in the identity of Courtland’s first wife. The pattern reaches its deadly and inevitable conclusion when, on the eve of their impending marriage, Michael searches the house for her, only to find the same terrible, familiar message pinned to the bed . . . “Do not call police. Be at home with $500,000 cash tomorrow if you want wife and daughter returned alive.”

Is it possible? Is he insane, or has the horrible scenario begun again? Frantic, out of his mind, Michael drives to the home of Robert LaSalle, awakening his partner and demanding a loan of another $500,000 in order to save Elizabeth/Sandra again. LaSalle? is in no mood to pamper Michael. Savagely, he taunts Courtland with his refusal, deliberately driving him to the very brink of insanity. It had all been a plot, in fact, to drive him insane. In Italy, LaSalle had recruited Sandra because of her startling resemblance to Elizabeth. Together, they had conspired to drive Michael mad and share his wealth. Enraged, Courtland murders LaSalle and then drives to the airport to take his revenge on Sandra who, he learns, is returning to Rome that night.

A shocker? Yes, certainly, but DePalma has held his greatest surprise, his master card, for the last. On the plane, Sandra sits alone while her own terrible memories come flooding back to her, as she recalls the mother and child being separated by the kidnappers. She remembers the awful explosion as Elizabeth Courtland is killed in the burning wreckage of the car, and herself, a terrified child, being led away to the airport by her “Uncle Robert” to be put on a plane bound for Rome. “Where’s my daddy?” young Amy Courtland cries. “Your daddy doesn’t want you anymore,” responds Robert LaSalle, himself grief-stricken and afraid of exposure. LaSalle had, in fact, engineered the kidnapping and ransoming of his partner’s wife and daughter. It was a plot to extort his partner, but the plan went awry. Elizabeth was never supposed to die. That hadn’t been part of the plan. After the accident, LaSalle had to cover his involvement. He couldn’t kill the child, so he packed her off to Rome, paid for her upbringing by an Italian family, and filled her young mind with hatred for her father.

The ploy worked. Sandra/Amy grew up despising her father. She still hated the father who had abandoned her, didn’t she? Didn’t she? But no. She’d come to love him during their brief reunion. He was, after all, her father. Consumed by remorse, Sandra steals into the rest room on the airplane and cuts her wrists.

In perhaps the film’s greatest moments, the airplane returns to New Orleans and a waiting Michael Courtland. Sandra has barely survived her attempted suicide and is being rushed in a wheelchair to the hospital. Michael, seeing the woman in the wheelchair approaching,‘ conceals the gun in his coat and walks toward her. Sandra awakens from her depression as she sees her father coming toward her. For Amy, it is a second chance to reclaim the love of her lost parent. For Michael, it is a second chance to kill the woman who deceived him. Amy leaves her wheelchair and races toward her father, arms outstretched, crying uncontrollably. Michael races too, but with revenge on his mind. Will he kill her? Will Amy have a chance to tell him who she really is, or will Michael lose his beloved daughter a second time? As she reaches his arms, they embrace and Michael points the gun at her head. He is about to pull the trigger when Amy cries out “DADDY!” Bewildered’, tears filling his eyes, Michael Courtland sees his daughter in his arms. Astonished, he holds her and says questioningly, “Baby?” It is a supreme moment of excrutiating drama, nearly unbearable in its intensity.

Courtland has suffered too much pain. DePalma, in his humanity, has allowed his creation to recapture his soul in a climax as daring and suspenseful as any cinematic moment ever committed to film. Recalling the lesson of the master, Alfred Hitchcock, that you musn’t lead an audience on and then cheat them, DePalma was able to wrench every ounce of suspense from his climactic reunion and still reward his audience with a fully satisfying. Emotional release. Without that all-important escape valve, Obsession might have lapsed into pointless cynicism and bitterness, but the hopeful, humanistic aspect of Brian DePalma’s cinema colored its conclusion, and Obsession is a far more powerful exercise because of it. The final imagery of father and daughter, forever lost then found, locked in a slow-motion dance of emotional intensity, is the most haunting and stunningly brilliant sequence in the complex cinema of this paradoxical director.

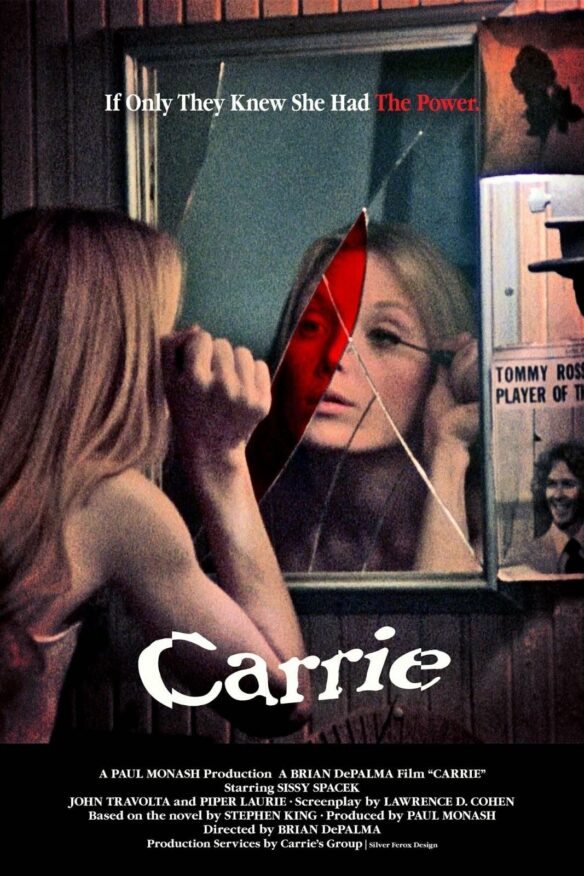

Perhaps Brian DePalma’s most tragic creation was the hopelessly sheltered, lonely high-school girl named Carrie. Based on the novel by Stephen King and released through United Artists in 1976, Carrie starred Sissy Spacek as the Cinderella whose magic wand concealed deadly telekinetic powers. Spacek shone as the fragile teenager, innocently unaware of her blossoming sensuality and savagely tormented by her classmates. This was truly a modern parable, an allegorical shocker based upon the classic story of Cinderella, replete with William Katt as the handsome prince, Piper Laurie as the wicked stepmother, and Betty Buckley as the kindly, understanding fairy godmother. Taunted by her peers, Carrie is magically transformed into the loveliest girl at school by a sympathetic teacher and escorted to the prom by the most popular boy on campus.

This is not Walt Disney, however, but Brian DePalma. Unlike the charmed and charming heroine of the fabled fairy tale, DePalma’s doomed Cinderella remains at the ball beyond the hour of twelve and must pay a terrible price. Happiness turns to horror as the wicked rivals drench Carrie in a pool of pig’s blood and crush the skull of her handsome Prince Charming. Innocence dies irretrievably, replacing youthful radiance with a newly awakened psychic power destined to decimate not only the wicked stepmother and her venomous “sisters” but Carrie’s fairy godmother and the entire magical kingdom as well. The school prom ends abruptly as blind hatred seizes Carrie, exacting a frightening payment from those who jealously coveted her crown. Carrie’s momentary castle, the high-school gymnasium, is consumed in a spectacular fire, claiming the lives of all who conspired to deprive her of her first chance for happiness.

Sissy Spacek is irresistibly innocent as Carrie White, a childlike waif with huge, alluring eyes and a guileless charm that radiates spiritual warmth and profound sensuality. She is a lovely, exquisite creature waltzing through an entrancing celluloid fantasy. It is this wide—eyed sense of wonder that the gifted young actress brings to the difficult role of the disturbed teenager.

Carrie is doomed by the awakening seed of her own pubescent self-discovery. As a troubled, friendless adolescent, she might safely have suffered in the shadows of peripheral life, assuming a benign invisibility. Forced into the dangerous arena of conspicuous social involvement, however, her peculiar vulnerability sets the ominous stage for her emotional assassination. DePalma’s sensibilities are obviously attuned to Carrie’s pathetic plight. Up until the predictable bloodbath that concludes the Stephen King story, Carrie is an unforgettable essay on teen-age cruelty and loneliness, a deeply sensitive commentary on societal alienation. The director, despite his personal empathy for Carrie, is forced to focus a bitterly realistic eye upon the fable. Fate, after all, had determined the course and brevity of her unusual life long ago. Carrie was always alone, always different. A well-ordered, structured society has little tolerance for those born outside its traditional mold. Carrie never would have fit in. She was unique. Therefore, she had to die.

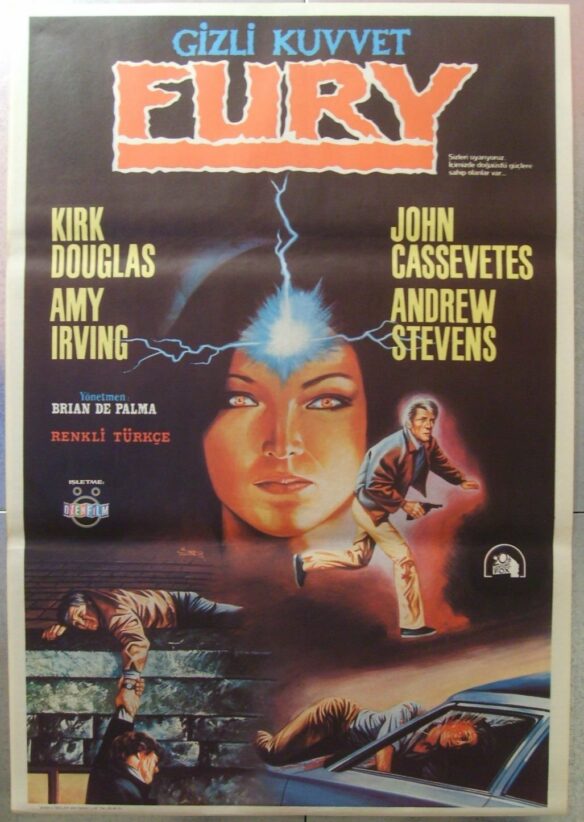

Recharging his creative energies, DePalma would allow two years to elapse before unveiling his next motion picture, The Fury, released by Twentieth Century-Fox in 1978. Remarkably similar in tone and treatment to the earlier Carrie, The Fury concerns the efforts of an ex-government agent to rescue his son from the clutches of a mysterious central intelligence agency bent on controlling the boy’s bizarre psychic abilities. Once again, a character’s fate is seemingly predetermined by an accident of birth and powers wholly beyond his understanding or control.

Peter, the boy’s father (Kirk Douglas), enlists the aid of a young girl with comparable psychic talents, and together they search for the captive youth. Amy Irving, the enchanting, sensitive young actress who played the single survivor of Carrie White’s wrath in the earlier film, portrays Peter’s confederate, Gillian, an impressionable psychic whose ominous visions portend impending tragedy.

It is difficult to distinguish between traditional conceptions of good and evil in The Fury. John Cassavetes as Childress, the determined American agent, is essentially amoral, a governmental clone unable to differentiate between right and wrong and lacking the basic ability to comprehend the difference. He walks somnambulistically through his assignments, neither knowing nor caring that he has become a corruption of the values he was sworn to protect.

Tradition has somehow undergone an ugly metamorphosis. Strict morality has polluted our concept of respect for authority and transformed it into a Hitlerian perversity. Representations of institutional justice have corroded conscience into amoral ambiguity. The federal agent we’ve been conditioned to admire has become a robot, a shallow descendant of the Third Reich obediently implementing the cruelest of directives.

The kindly research director at the psychic institute (Charles Durning) betrays his scholarly integrity by acting in frightened complicity with the federal agency. Dr. McKeever is a modern Caligari, a Kafkaesque caricature simply carrying out the will of the state. Tradition and trust have vanished quietly, frighteningly, without revolution or rebellion. DePalma has murdered our most precious illusions of natural order. In this dark society, we are the villains.

Despite Peter’s heroic effort to save his son, it becomes painfully apparent that it is an exercise in futility. It is too late. The boy (Andrew Stevens) has endured too much ugliness to have survived unscathed. The evil effect of his captivity has warped his fragile mind, expunging his conscience of all responsibility. Corrupted by his environment, he undergoes a terrible transformation. His powers channeled into negative energy, Robin becomes a frightening superbeing—a monster.

Kirk Douglas, as the concerned father, delivers his most restrained and intelligent performance in years. Accompanied by the brooding brilliance of John Williams’s masterful score, Peter and his only child are swept beyond salvation, engulfed by merciless tides of evil, in all-consuming intensity. Once again, the unsuspecting have lost their fight for survival in a game whose cards were already stacked against them.

In Dressed to Kill (Filmways, 1980) DePalma focused upon another kind of human frailty–sexual excess borne of a repressive society. Kate Miller (Angie Dickinson) is starved for affection, seeking male companionship in order to satisfy her needs. Liz Blake (Nancy Allen) is, on the other hand, a prostitute, reimbursed handsomely for her ability to satisfy the needs of her clientele. At either end of the spectrum, the judgments imposed by society on its inhabitants have created the climate into which both women were born.

Sexual yearnings, however normal, however human, are denied by vast segments of society intent on ignoring or invalidating their natural instincts and imposing their values on the remainder of an already confused species. The search for personal identity or the fear of what that search might reveal has, historically, negated our sexual birthright. “Sin” became an easy, simplistic catchphrase for burying our genitals under the sands of fear and ignorance. We protest too much, as someone once said, creating the seeds of emotional conflict and pain.

When pressure beneath the earth’s crust has been contained and suppressed for too long, it builds to a terrible climax and explodes. We are all products of this earthly terrain. Like the smoldering rock beneath the surface, the natural inclinations of human beings cannot be denied. When the pressure becomes too intense, people erupt as well.

Kate Miller’s pathetic sexual escapades, like a deadly vacuum, pull her into a black, bottomless well from which there is no escape. In a handsome sequence apparently modeled from the museum interlude in Hitchcock’s Vertigo, Kate plays a highly sexual game of cat and mouse with a patron of something more than the arts. Canvassing the canvases at New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art, her gaze lingers hungrily on the sight of an attractive man. Sensing that he is being appraised, the man turns to acknowledge the bidder. Discovered, Kate turns self-consciously, walking slowly, deliberately through a maze of twisting corridors, aware that she is being pursued and luring her admirer confidently through his moves. Tiring of the game, the mouse changes the rules. The chase is reversed, and now Kate retraces her steps, drawn to the irresistible bait through the same mad maze.

The scene is charged with sexual tension as the camera dances through the ever-winding corridors, frantically surveying every corner for evidence of the manipulative Mouse Who Would Be Cat. Kate’s heavy breathing intensifies, dominating the soundtrack with a desperate urgency. The entire sequence is literally orgasmic, an electrifying display of filmic artistry in which the mating of sight. and sound combines to create the illusion of passionate sexual foreplay without the luxury of the slightest physical contact. The tension abates momentarily as Kate loses the prey, as well as her glove. Frustrated, she walks down the steps of the museum, only to be greeted by the sight of the missing glove dangling seductively from the open window of a parked taxi. The scene reaches its climax as she reaches for the glove and is pulled into the cab by the cat, joyously exacting his pound of flesh on the back seat. Kate’s sexual abandon is complete. Her screams of ecstatic excitation are engulfed in waves of frenzied sound as the cab comes to a screeching halt in front of the man’s apartment.

The moment has been consummated, but the moment is gone. Now Kate must pay a horrible price for her altogether human indiscretion. Leaving the apartment in the middle of the being exposed, she is confronted by a crazy woman on the elevator, wielding a straight edged razor, and hacked to death in a nightmarish scene of “moral” retribution. Kate never had a chance of surviving her weakness, for this was the ultimate betrayal of trust. The murderess was in fact Dr. Elliott (Michael Caine), her own psychiatrist who, like Norman Bates in Hitchcock’s Psycho, led a double existence as a man and a woman. Elliott’s masculine self was attracted to Kate. When his own longing for her became too strong, his feminine ego took control and, in a jealous rage, killed the girl. Despite her struggle to regain a foothold in the course and meaning of her destiny, Kate was a loser, and in this, the final game, the price was her life.

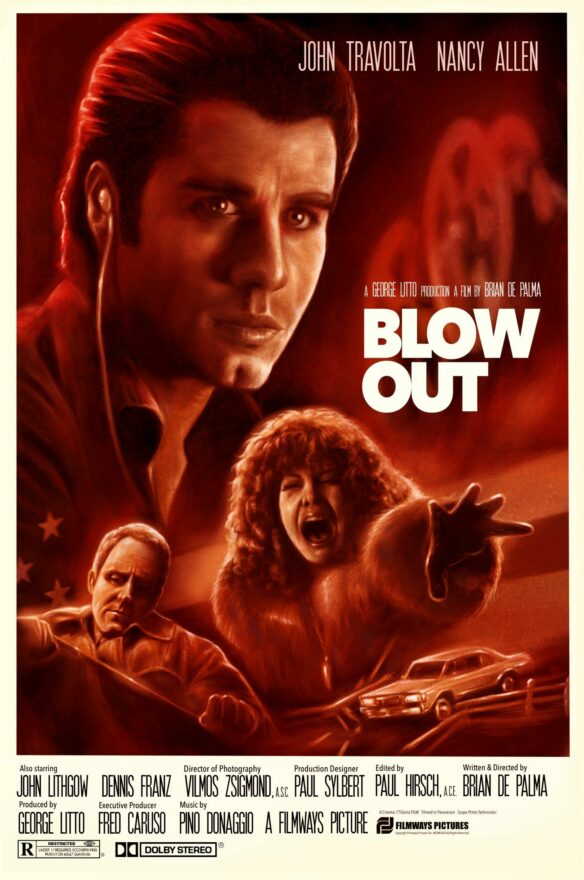

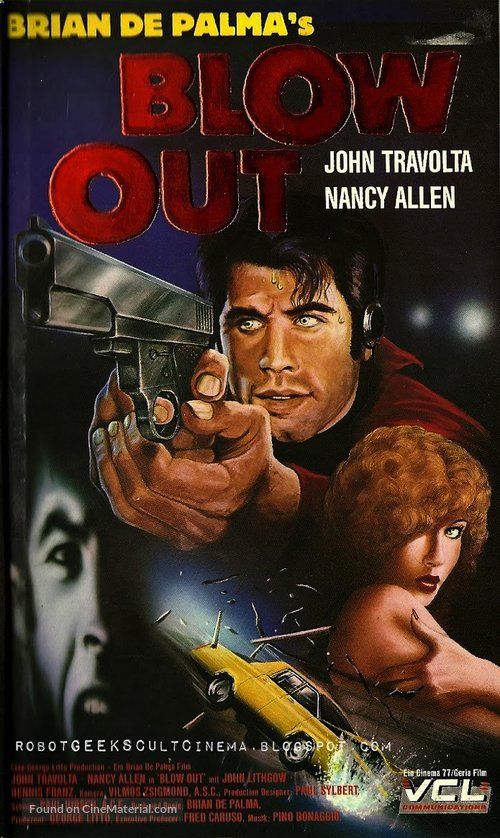

With Blow Out (Filmways, 1981), Brian DePaln1a has reached a new level of artistic maturity. Filmed in its entirety in Philadelphia, this brooding, disturbing film tells the deceptively simple story of a politician and his female escort whose car races off a dark road, plunging its occupants into the murky waters of the Wissahickon Creek.

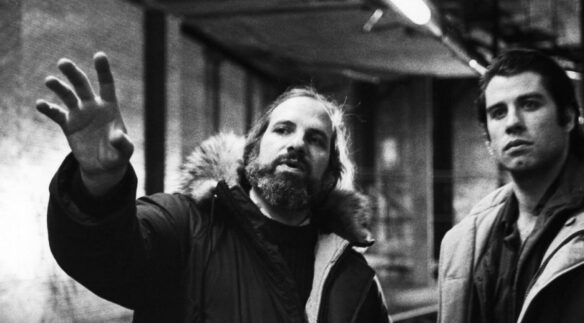

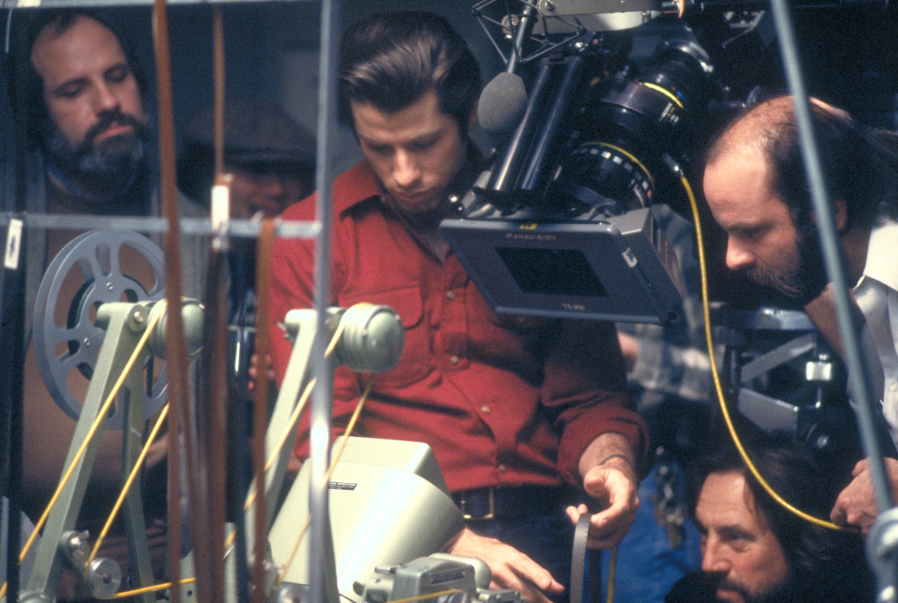

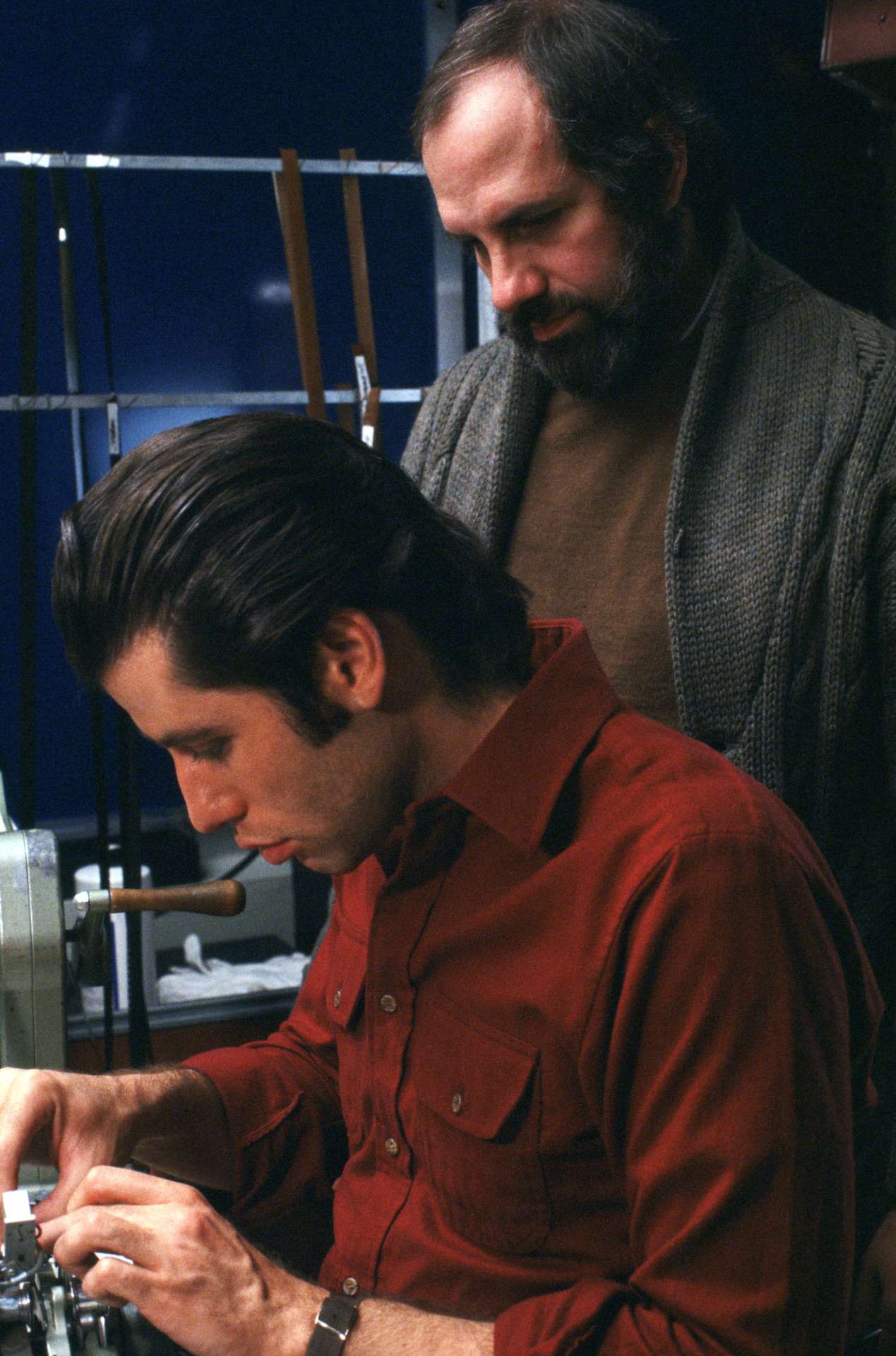

Written and directed by DePalma, the film is a darkly successful thriller about the underbelly of political intrigue out of control within the normally safe boundaries of civilized society. Utilizing Hitchcock’s familiar scenario of an ordinary man caught up in extraordinary circumstances, the director uses john Travolta’s boyish innocence as the unwitting bait that lures a crazed assassin from out of the shadows. Travolta, in perhaps the most understated performance of his career, seems content to surrender his notoriety to DePalma’s masterful manipulation of people, places, and events.

Jack (Travolta), a sound man for a small motion picture company, inadvertently records the sound of the politician’s tires blowing out just before the fatal accident. Did they blow out, however, or were they blown out by rifle fire? Sally (Nancy Allen) is the girl whose life and reputation are savagely compromised by the accident. Rescued from a watery grave by the technician, she wants only to fade into the background and escape the inevitable lurid publicity. The allusions to Senator Kennedy and his celebrated accident are obvious, except that in a novel twist it is the girl who survives the crash and not the politician.

A massive cover-up is under way when it becomes apparent that ]ack’s recording can prove that the “accident” was an act of political assassination. Since the public is unaware of either the girl or the murder, the pair must be silenced permanently. Burke, the killer (John Lithgow), is given the assignment of tying up the loose ends. Like Childress in The Fury, Burke is a machine devoid of values or compassion. He understands only that he has left a job incomplete and that he must finish his work.

Vilmos Zsigmond’s shattering cinematography succeeds in turning Philadelphia into an eerie, surrealist nightmare world in which every darkened corner seems to verge on the brink of exploding into violence. The City of Brotherly Love is presented in an astonishing panorama of stark and menacing set pieces that seem to recall Hollywood’s memorable cinema noir period of the 1940s in which the city preyed upon its captives.

Jack and Sally are captives within the walls that keep them prisoners. They struggle valiantly to survive, but their fate relentlessly succeeds in tracking them down. Along the way, however, DePalma infuses the picture with haunting, unforgettable moments of directorial brilliance. The city’s famous 30th Street train station is transformed into a dangerous den of cold and menacing mechanization, gazing with cyclopean eyes at the tiny, fragile form of a vulnerable young woman being stalked by the calculating killer. A parade celebrating long years of independence and liberty turns into a nightmare as Jack’s jeep races through congested streets in an effort to catch the subway train beneath his wheels and prevent Sally’s death. In a stunning tour de force of expert cinematography and direction, Zsigmond and DePalma capture the sequence from high above the city, looking down through the doors of a helicopter as Jack leads the police on a thrilling chase through the very grounds of City Hall courtyard. The daring stunt climaxes as the jeep crashes through the huge display windows of Wanamaker’s department store. Finally, in the most dazzling sequence of the film, Jack searches through the rubble of his ransacked studio in order to find the incriminating tape containing the murderous blowout. The camera surveys the room in a dizzying, continuous, circular panning shot, observing the destruction detached, without comment, as Jack floats in and out of camera range. It is a superb achievement.

Always a moralist, DePalma completes his essay in a profoundly moving finale that will haunt filmgoers for years to come. The bitter irony of the director’s vision is that life leaves no one unscathed . . . that the users are themselves finally used up.

At the last, Burke lures the innocent Sally away from the crushing crowds continuing their celebration into evening. Recovered, Jack tries desperately to work his way through the parade and find the killer before it is too late. Carrying his recording equipment, he eavesdrops once more on the sounds of a murder in progress. Grief-stricken, unable to locate the source of Sally’s terrible screams, Jack overhears the death agony of his lover.

Early in the picture, in a comedic interlude, Jack tries fruitlessly to simulate a convincing death scream from a series of hopelessly inept actresses to add to the soundtrack of a horror film. Now, in the final devastating moments of Blow Out, DePalma adds the last pathetic touch. Jack, ever the professional technician, uses the recording of Sally’s final, agonized screams to fill in the soundtrack of his picture. In this ironic symbolism, it becomes clear that DePalma has created a work of profound and enduring importance, a unique and wholly original film peculiar to his own developing style as a creative filmmaker.

Yet, Brian DePalma is essentially a purist, and the spectacular journey from opening credits to end titles is pure cinema, exciting and exhilarating. Blow Out is a major work from one of this country’s most shamefully underrated film directors. It’s time that the rating changed. A complex and serious talent, De Palrna’s ever-emerging flair for combining exuberant directorial genius with sober, provocative writing has already earned him a place of importance in modern cinema. In whatever guise, however, serious or sardonic, DePalma is always dressed to thrill.

[Appeared originally in George Stover’s CINEMACABRE Magazine in 1982.]