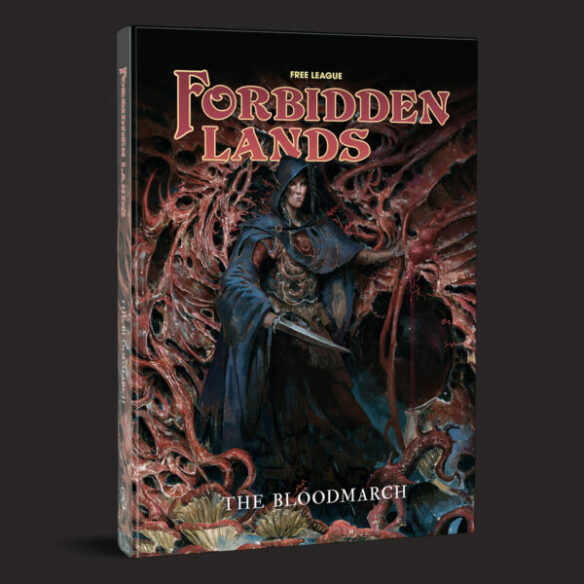

Forbidden Lands Book of Beasts by Andreas Marklund and Henrik Rosenborg (Free League, 2023)

By Warner Holme: Andreas Marklund and Henrik Rosenborg’s Forbidden Lands Book of Beasts contains more than the name would imply.

Quite early in the book on the page 6-7 spread we already begin to see the talent and quality that went into the volume. There is a wonderful pencil style drawing and summary about a creature called an amphibian. In addition to providing a lovely example of the ugly cute aesthetic, the right up gives a delightful example of a morally complicated creature that can be seen as more than cannon fodder. Instead motives like religion, survival, and family paint a picture where the creatures can be allies or enemies depending upon the circumstance.

Other creatures scattered throughout are given similar levels of detail and explanation. Some of them are quite universally a danger to people of any type, such as the entertaining and clever adaptation of the “Mara” starting on page 54. Yet even knees are detailed with not only abilities and mechanical details, but also a variety of situations as well as environmental and behavioral details to make them believable within the world of the game.

Detailed selections for encounters which might bring out a variety of the creatures described in this book are given a little later, and while the charts may not be appreciated by many the multiparagraph setups are delightfully entertaining reads. Many of these refer back to classical fantasy tropes like page 133’s “Petrified Troll” while others take a more naturalistic approach like the very next pages “Monster Droppings” which touches upon some rarely used in fiction biological functions.

One of the strange aspects of this volume comes in the section on page 165, the “Solo Rules.” A set of charts and detailed explanations for how to essentially run the basics of A game with no one else, it is a very nice supplement for any individual who wants to try it alone. That said while it seems well thought out and constructed, it is a strange addition to a book which purports to be about the creatures and beings populating the setting. This and, to a lesser extent, the section on “Gamemaster Tools” feel like they might be better suited to another volume, however are such major elements they are likely to be appreciated by anyone playing it as a game.

One of the more surprising elements of the book comes up to a start with an illustration on page 98 and a description on page 99. This would be the entertaining yet very oddly named “Twisted Ent.” While making perfect sense in relation to that name, the strange tree creature seems a surprise and light of the fact that certain rights holders related to the works of J.R.R. Tolkien have gone out of their way to make other fantasy authors and game creators change the latter of those two words to something else for any strange tree creature. Only time will tell the future printings of this book have a similar result.

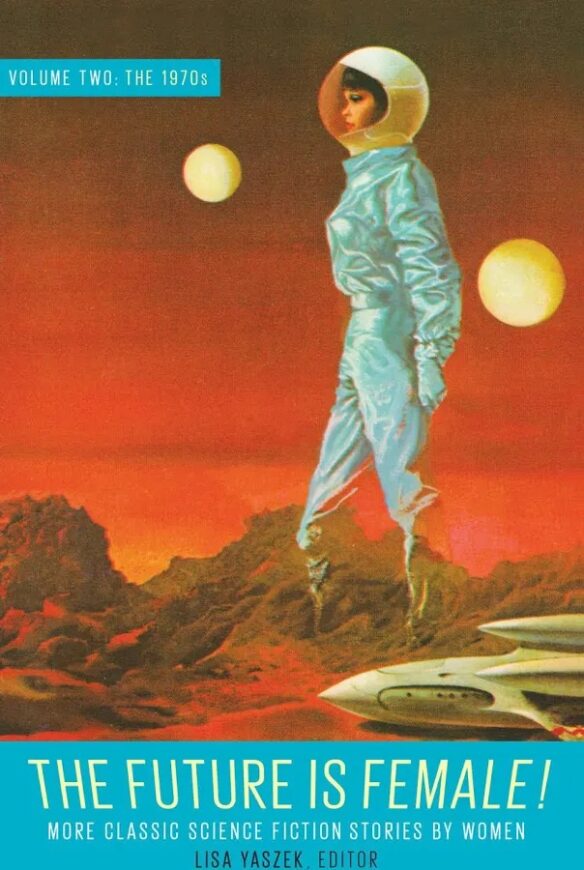

With its dark blue leather-like binding this volume is marked off as a more major release than many of the other supplements to the game. The gorgeous art from the field of corpses and papers to the little sketches of bottles would be greatly appreciated by anyone flipping through it. To fans of the game as it already exists this particular book is likely unmissable. For someone looking for ideas or entertaining little Snippets of information about creatures and places it’s certainly not a bad experience either, although some of the material is certainly likely to be skimmed over by the non-gamer.