By James H. Burns: Recently, a television mini-series based on Arthur C. Clarke’s classic novel, Childhood’s End, debuted internationally. But if the vagaries and fortunes of Hollywood had been just a bit different, there could have been such a production, or a theatrical feature film, far sooner, from Universal Studios–

As discussed in this interview I conducted over thirty–five years ago with the earlier project’s writer/producer, Phillip DeGuere Jr.

DeGuere began his career at Universal in the late 1960s, writing for such shows as Run For Your Life, and one of my all-time favorite series, The Name of the Game (“A Hard Case of the Blues.”) He went on to write for Alias Smith And Jones, Baretta, City of Angles and for such genre efforts as The Invisible Man, on NBC, and The Bionic Woman (and most notably, perhaps, writing and directing, and serving as the executive producer for, the 1978 Dr. Strange pilot on CBS, based on Steve Ditko’s and Stan Lee’s Marvel Comics character).

(When we met, DeGuere also told me he had devoted a great deal of time to what was hoped to be a major documentary/concert film with the Grateful Dead music group. He also had just worked on a new project with actor Robert Blake. He had been expecting the worst, having heard that Blake could be difficult to deal with, but was happily surprised that the actor/producer was concerned entirely with the quality of the endeavor’s writing.)

DeGuere’s career after the Childhood’s End endeavor explored here was even more notable: creating the television series Whiz Kids; working on the 1985 Twilight Zone revival, and creating and producing Simon and Simon. He was also a consulting producer for some episodes of NCIS and JAG.

DeGuere was only sixty years old, when he passed in July of 2005.

Intriguingly, his unproduced adaptation of Clarke’s book probably did wind up having a huge influence on 1980s television science fiction. His script had been around Universal for years, when V — the hit mini-series about an alien takeover of Earth — debuted in 1983.

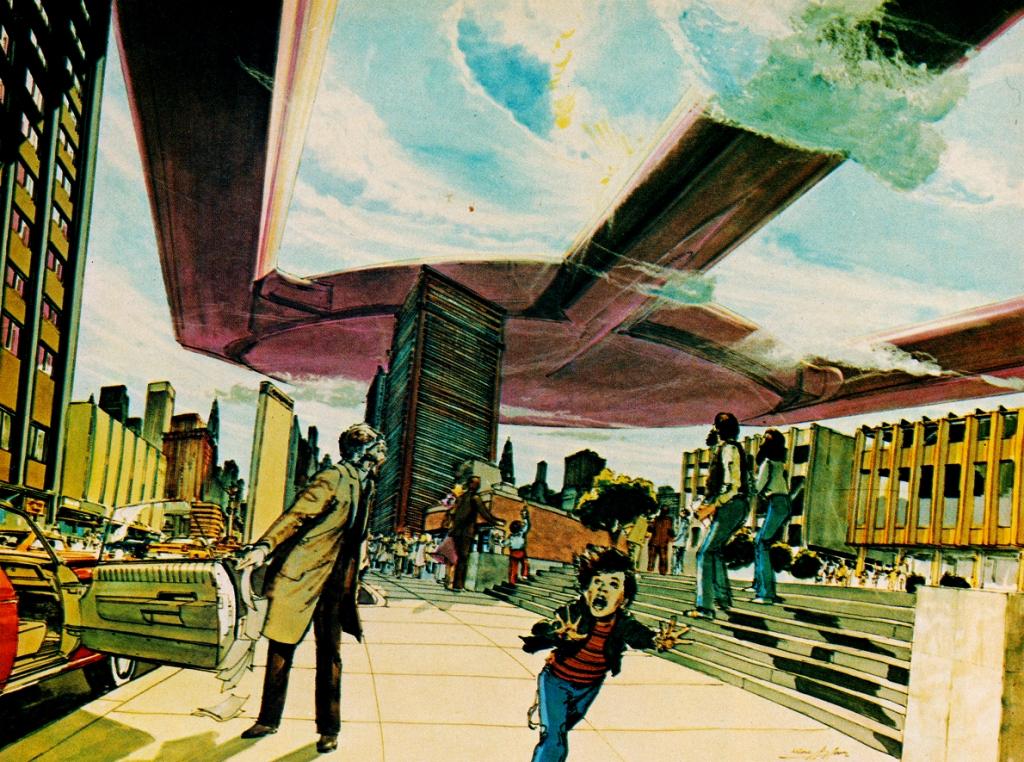

The program’s opening sequences — and a key marketing image — of alien ships hovering in the skies over the world, are almost identical to those in Clarke’s epic.

¶

“The power of Childhood’s End remains undiminished as the years go by,” says Phil DeGuere, a Universal Studios producer-director-writer (Black Sheep Squadron, Dr. Strange). “The real reason for making the picture is because the story is worth telling to a large number of people. It fills you with a sense of wonder and enlightenment. Childhood’s End is one of the few science fiction novels that even people who don’t like science fiction enjoy. But, unfortunately, people in this business tend to be shy of innovation.” Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End was first published in 1953 and has since become one of the genre’s most influential and bestselling novels. The book concerns man’s encounter of an apparently superior race named the Overlords and the future development of mankind. What Phil DeGuere is hinting at in his opening statement is that for the past year, his telefilm production of Childhood’s End (originally announced in the late 1970s), has been stalled due to various legal and financial entanglements. Perhaps DeGuere shouldn’t be surprised at this stasis, however, considering Childhood’s End‘s bizarre past as a film project.

Kicking around Hollywood as a viable movie property since the middle ‘fifties, Childhood’s End resurfaced for celluloid potential in 1975 when the late Gene Kearney, one of Universal’s best writers and producers (Night Gallery, Kojak, Games), realized that his studio owned the novel’s option.

“That was two years before Star Wars, so I think it’s safe to say that nobody had a very good idea of what was involved in bringing a picture like Childhood’s End to the screen,” DeGuere remembers. “When Gene left Universal in 1977, I kind of inherited the idea of trying to develop Childhood’s End.”

Phil soon discovered that the novel was in “turnaround” to producer George Litto, a former Universal staffer, who had been interested in Childhood’s End while still with the company. This meant that while Universal technically owned the book’s rights, Litto was enabled to sell the project to another company.

“It wasn’t until Star Wars came out — which is typical of the studios — that all of a sudden everyone wanted to jump on that particular bandwagon. Then Universal became actively concerned and took the necessary steps to bring Childhood’s End back.”

Childhood’s End was initially going to be produced as a six-hour mini-series for CBS. When that fell through, ABC told Universal that they wanted the property as a two- or three-hour feature.

“That was the summer of 1978,” DeGuere recalls. “We would have proceeded aggressively on trying to pull the project off, but then it became known that the contracts that had originally been written with Arthur Clarke were so old–some of them dating back to 1957–that several of them had expired. It took a month-and-a-half just to get a lawyer to dig up the contracts and read them in order to verify that we had lost the rights to some aspects of Childhood’s End. It took another nine months to resolve the stalemate between the lawyers representing Universal and Arthur’s people. That was the major delay once we actually had a go-ahead from the network. The new contracts stipulate that Universal retains all rights in the galaxy or the universe. They’re thinking fairly down the line…”

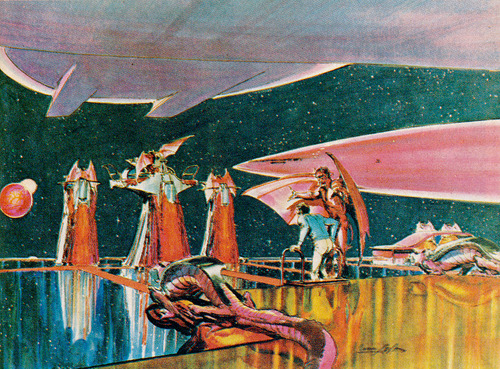

During that nine month period, DeGuere wrote a seventy-page treatment for the film in which he feels that he solved many of the problems inherent to adapting the novel to celluloid. The only major change Phil instituted was promoting Jan Rodericks, the black youth who becomes the only human the Overlords permit to watch man’s evolution, to a character that appears throughout the entire story.

“That was done to unify the film,” DeGuere explains, “because except for Korella, the events and characters in the first half of the book are not related to the elements and characters in the second half of the book. That could have been the telefeature’s only fault. It doesn’t feel right to ask an audience to sit for an hour-and-a-half and get to know some characters and a story and then suddenly jump twenty-five to fifty years in the future and start a whole new story. You need some kind of satisfactory link to work as a framework. Having Jan Rodericks not only finish the story but start it as well seems to work beautifully.”

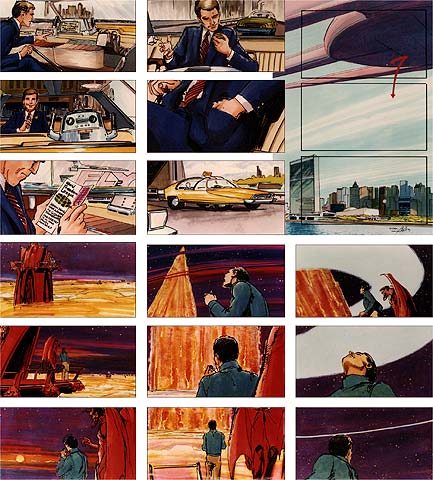

The legal difficulties were finally settled around January of 1979. Phil began writing a full screenplay and commenced pre-production. One of DeGuere’s first moves was to hire Neal Adams, the noted comic book artist (also known for his Tarzan paperback covers, and involvement with the science fiction theatrical play, Warp), as a production designer.

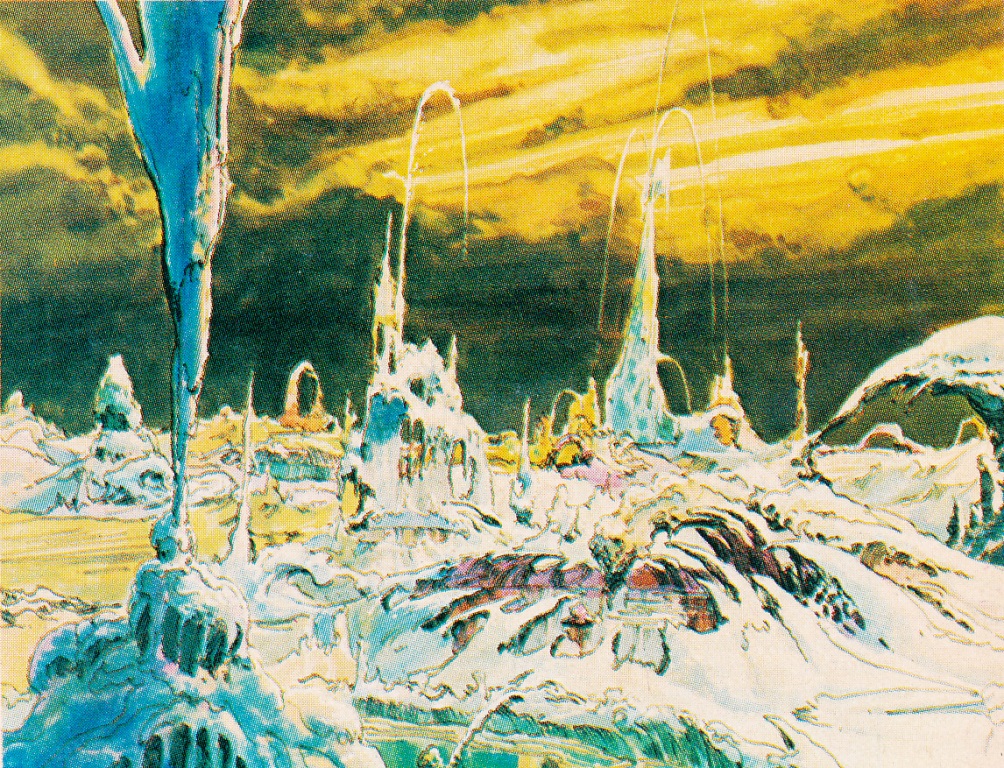

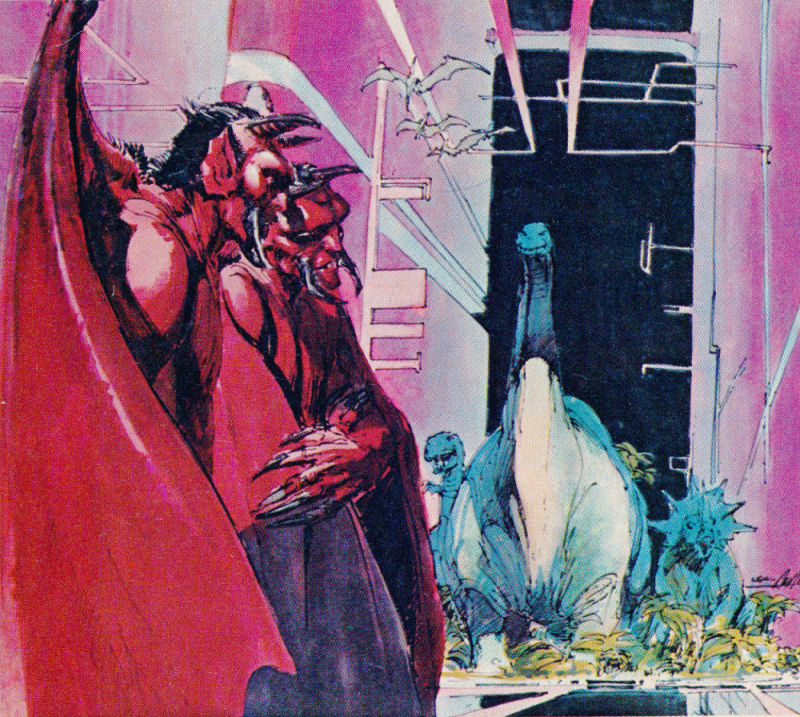

“I think that comic artists are particularly adept at condensing single story elements into single pictures,” says DeGuere. “Neal Adams has always been one of my absolute favorite artists and it was one of those happy coincidences that I was able to get him. Neal has a unique ability to take a scene, read it, interpret it, understand it and figure out a way to make it look right in a painting. It is a hell of a lot easier to have a single drawing or painting that you can take around to the technical people in the movie business, and say, ‘This is what I want to see on the screen,’ than to write a page of description in the screenplay and have various people interpret that and do it whatever way they like. We also had a couple of pieces of artwork done by an amazing visionary named Anthony Scott Thom. There’s an incredible range of artists in this country who have become fascinated with fantastic themes. They make a talent pool that you naturally want to tap into when you do a picture like Childhood’s End.”

DeGuere also began exploring how Childhood’s End ‘s special effects requirements would be effectively executed.

“My concern has always been for adequate resources,” DeGuere comments. “I’m confident that Universal will let me film a faithful adaptation of the novel, but we need enough money to do it right. There aren’t too many people around who can do the kind of special effects and makeup required for Childhood’s End.

“Some of the effects might require slightly changing the story. I don’t think,. for example, that we could realistically show the Overlords’ spaceships coming over New York City during the day. As soon as you start dealing with blue skies and clouds, you run into horrendous effects problems. It may be a lot smarter for me to have a spaceship coming in at night, hang over the city and flash some lights and then go into orbit–at which point I don’t have to deal with the problem of matting the spaceship against a blue sky. I’, compromising, but even with a forty million dollar budget, you might not be able to successfully put the ships against a blue sky. For me, this type of film has to be done right, or not at all.”

DeGuere also established contact with Arthur C. Clarke, to insure the property’s integrity.

“What little we talked about seemed to meet with his approval at the time,” DeGuere says with a smile, “but it was hard to get too many specifics talking to a man I had never met at 1:30 in the morning my time.” (There is an eleven-and-a-half hour difference between California and Sri Lanka.) “He approved of my boosting Jan Rodericks’ role in the story and also my elimination of the kidnapping of Stormgren. Arthur revealed to me that the abduction had been an element that existed in an earlier novella that he had incorporated into Childhood’s End and that it didn’t really pay off as far as the overall structure of the book is concerned.

“More recently, I wrote him a letter explaining that the production’s been held up for a while, which I think he might have suspected was going to happen. Unfortunately, I didn’t have a hall of a lot to say to him. I told him that I was really embarrassed by the situation, but I guess Arthur’s been through this before with other projects. When the film gets going again, I’ll hopefully be able to meet with Arthur and get as much input from him as possible.”

Childhood’s End ‘s limbo telefilm status is somewhat difficult for DeGuere to understand. He had originally thought that Universal was simply waiting to make sure that Star Trek: The Motion Picture and The Black Hole would both be relatively successful before proceeding into production.

“Maybe now they’re waiting to see how Dino DeLaurentiis’ Flash Gordon will do,” DeGuere speculates. “Certainly, if that film is successful, it would be a good impetus to reactivate Childhood’s End. The novel really doesn’t fit the kinds of categories that SF films and television have always done. You almost have to look at filmed science fiction as a completely separate phenomenon from written science fiction. It’s very rare that it’s made an adequate transition. Science fiction movies have always fundamentally been exploitation films. There really isn’t much precedent for trying to adapt a science fiction novel as a work of literature.”

If Universal and ABC find Childhood’s End ‘s cost prohibitive for television (DeGuere estimates the picture’s budget at roughly ten million dollars), could the novel find life as a theatrical release?

“Universal has recognized Childhood’s End ‘s potential as a feature film presentation,” DeGuere replies. “As I understand, however, it’s somewhat more attractive for them to consider making pictures of this nature where their financial involvement is limited, like on Flash Gordon. That may change, but there are other factors, from the studio’s point of view, the story doesn’t have the elements that are time tested for theatricals. Childhood’s End doesn’t have a clearly etched battle between good and evil, a group of people running around shooting at each other, a great deal of jeopardy, or a life and death situation as far as the characters are concerned. I’m inclined to think that a feature film would be a crossover situation, where adults would see it because of the story and kids would want to see it because of the aliens and spaceships. The merchandising prospects of the Overlords are certainly intriguing.

“The major audience for movies might have to mature before we can do a feature,” DeGuere continues. “Presently, the target audience for motion pictures is teenagers. The majority of films are therefore designed for an even lower common denominator than television. But I think that there’s a kind of demographic change taking place. The age of the largest segment of the country’s population is rising for the first time in over thirty years. All this translates into my mind as meaning that little by little the target audience for motion pictures will have to grow older. Films will have to reflect the mass’ matured tastes. It’s possible that the fundamental factor for Childhood’s End ‘s future really involves a change in which this industry makes it decisions.”

Another possibility is that an independent producer could approach Universal and either buy the rights to Childhood’s End or offer a co-financing agreement.

“That might be the way it has to happen,” DeGuere admits, “because in order for this picture to get made at Universal, somebody in a high decision making position is going to have to make a personal commitment to go ahead with the project. It requires that kind of courage which is not necessarily the long suit of this industry’s executives.”

If another studio does buy the rights to Childhood’s End, would DeGuere try to become involved with the new production?

“I probably wouldn’t have to do that,” says DeGuere, “because if somebody were to buy the rights from Universal, they’d get a copy of my script as part of the sale. Naturally, I don’t think anybody’s going to come up with a better script. Anybody sensible enough to know what they were buying would read all the available material. Hopefully, they’ll realize that they had a good adaptation in my screenplay.”

The events surrounding Universal’s development of Childhood’s End could help explain why there aren’t more capable producers handling television science fiction. Like several producers before him, DeGuere has run into so many delays that he might be understandably wary of initiating future science fiction oriented productions.

“I don’t think that that’s going to be the case,” says DeGuere. “There are so many frustrations and roadblocks that you run into naturally in films and TV that I don’t think it’s likely that any of us are going to get that discouraged.”

DeGuere has already completed a pilot script for ABC which he described as “The Six Million Dollar Man meets Carrie,” and also maintains hopes for a mini-series based on Larry Niven’s and Jerry Pournelle’s Lucifer’s Hammer. At the moment, Childhood’s End is basically ready to start rolling. Once the telefeature gets a go-ahead, it would still be a year away from actual production, but “ninety percent of the problem is solved,” in that the book is adapted and DeGuere has a completed script.

If Childhood’s End lays on the shelf, Arthur C. Clarke’s brainchild might appear in other media. Broadway producers have shown interest in bringing the story to the stage and, at the very least, some publisher might release a special edition of Childhood’s End utilizing Neal Adams’ preproduction paintings and sketches.

But Phil DeGuere isn’t content to watch Childhood’s End “appear in other venues.”

“Most producers have in the back of their desks those one or two very special projects that they have always wanted to make and never forget,” says DeGuere. “In my case, Childhood’s End is one of them. If I were suddenly catapulted into a position of great clout in the business and was given a blank check, it’s very likely that I would immediately get Childhood’s End launched.

“The other thing is that, fortunately, it doesn’t necessarily require me to reach that position. I get a lot of phone calls every week from people all around the world showing interest in the project. I would like nothing better than for somebody to come along and get the film made.

“I guess what I’m trying to say is that it’s inevitable that Childhood’s End gets made. At one point, it’s bound to happen…”

Original Article © Copyright 1980 James Burns

Revised Version © Copyright 2016 James H. Burns