By Steve Vertlieb: Jerry Goldsmith’s work for the motion picture screen encompasses some of the most excitingly original music written for the movies over the second half of the 20th Century.

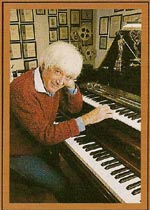

Born February 10, 1929 in Pasadena, California, Jerrald Goldsmith determined early on that the course of his life would be musically themed, but his earliest aspirations were swiftly sidetracked when he realized that his dreams of composing music for the concert hall would yield infrequent fruit. Artistically precocious, he would study piano at age six and begin his studies in composition, theory, and counterpoint at age fourteen under the tutelage of both Mario Casteinuovo-Tedesco and Jacob Gimpel.

It was Miklos Rozsa’s Oscar winning score for Alfred Hitchcock’s 1945 suspense classic Spellbound that first inspired the gifted teenager to write music for the visual arts and, in later years, he studied under Rozsa at the University of Southern California. Goldsmith found employment in the music department at CBS as a clerk typist in 1950, but was soon writing original music for radio programs like Romance, and the prestigious CBS Radio Workshop.

Remaining with the network for most of the decade, Goldsmith would compose thematic material for both the critically acclaimed Playhouse 90 TV series, as well as music for the weekly program Climax.

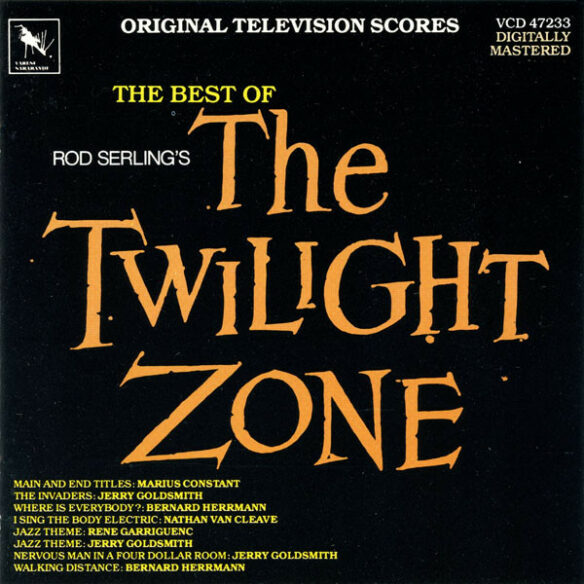

In 1957 he scored his first full length motion picture, the Western film Black Patch, and in 1960 began writing original music, along with Bernard Herrmann (from1959), for Rod Serling’s iconic science fiction/fantasy TV series, The Twilight Zone.

In 1960, Goldsmith was hired by Revue Studios to score their new weird fiction anthology series Thriller, which was hosted each week by the distinguished actor, Boris Karloff. Goldsmith, together with Morton Stevens, would write much of the significant body of work composed for the legendary horror program. Goldsmith continued to write for television, most notably for NBC’s popular Dr. Kildare program, as well as the James Bond-inspired, network secret agent series, The Man From U.N.C.L.E.

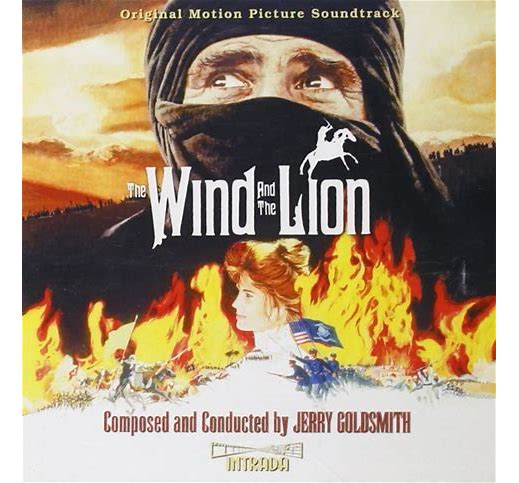

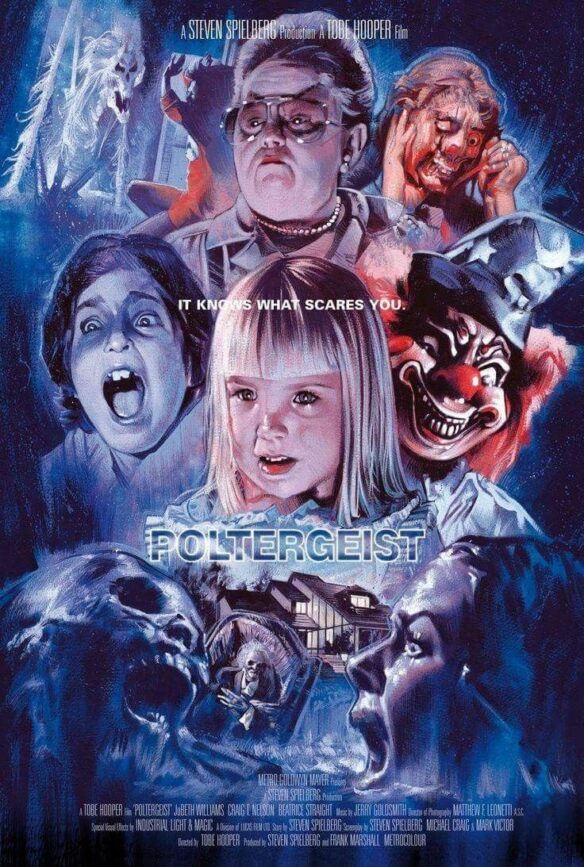

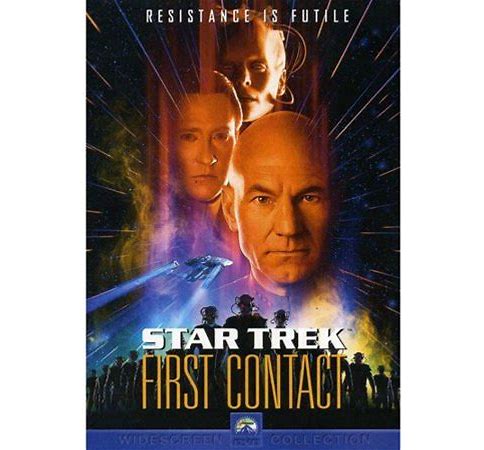

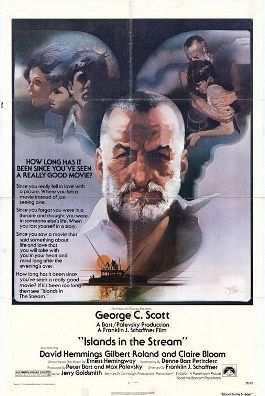

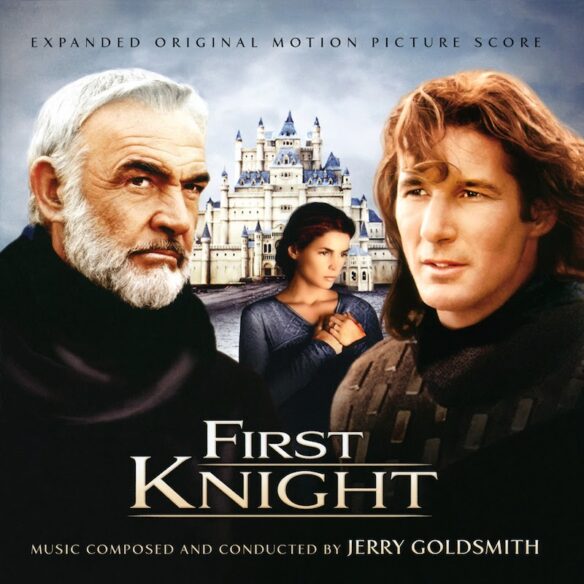

In 1962, Oscar winning composer Alfred Newman persuaded Universal to hire Goldsmith to write the music for their modern Western drama, Lonely Are The Brave, starring Kirk Douglas. He went on to score an astonishing variety of films including The List of Adrian Messinger (1963), Fate Is The Hunter (1964), In Harm’s Way (1965), the ethereal score for The Blue Max (1966), The Sand Pebbles (1966), Planet of the Apes (1968), the lonely, brooding themes for The Detective (1968), Patton (1970), The Wild Rovers (1971), Papillon (1973), the magnificent score for The Wind and The Lion (1975 – perhaps his greatest work), Logan’s Run (1976), The Omen (1976), the haunting score for Islands in the Stream ( 1977), Capricorn One (1978), Alien (1979), his spectacular signature score for Star Trek: The Motion Picture (1979), the exquisite, yet chilling rhapsodies for Poltergeist (1982), Twilight Zone: The Movie (1983), the delightful Gremlins (1984), Hoosiers (1986), Total Recall (1990), the tragically discarded music for Legend (1985 – ironically, the poetic musical legacy of this troubled film), the lovely, lyrical themes for Medicine Man (1992), the majestic and heroic score for First Knight (1995), and The Mummy (1999).

During his career, Jerry Goldsmith would compose the music for two hundred fifty-two motion pictures, win seventeen nominations from The Academy Of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for his efforts, and win a single Oscar for his music for The Omen in 1976.

His final film score was for the insanely inspired comedic tribute to the Warner Bros. cartoons, Looney Tunes: Back In Action (2003) for his old friend, director Joe Dante. He passed away far too prematurely from the rigors of cancer on July 24, 2004. He was seventy-five years young. Within mere weeks of his passing, two more of cinema’s great dramatic composers would also, remarkably, come to the end of their own mortal journeys…first David Raksin, and then Elmer Bernstein. It would become the most tragic month in the history of motion picture music…the “day” the music died.

Yet, the music lives on in recorded recollection. Two of Goldsmith’s works have been accorded exhaustive, archival tribute in stunning new two disc releases of his original soundtrack scores, while a third major label is releasing a brand new concert recording of the composer’s science fiction scores, both on DVD, and packaged together with an accompanying CD.

FIRST KNIGHT

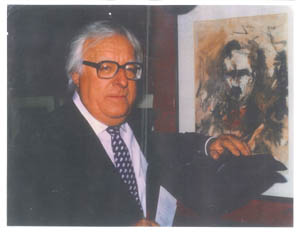

La-La Land Records has released a stunning complete recording of Goldsmith’s breathtaking score for Jerry Zucker’s monument to heroism and mythic chivalry, First Knight. Zucker felt that Jerry Goldsmith was the perfect choice to score his 1995 release. Goldsmith had become known as a master of romantic, swashbuckling adventure, writing wall to wall symphonic panoramas for grand and glorious spectacle, much as had Erich Wolfgang Korngold at Warner Bros. in the nineteen thirties for the joyously valiant films of Errol Flynn. The thrilling nobility of Goldsmith’s heroic themes accompanying Sean Connery in The Wind and the Lion are among the most emotionally stirring and viscerally exultant scoring in film history. Visionary writer and poet Ray Bradbury felt so exhilarated by that music that he was inspired to write a novella based upon his own, deeply felt, personal experience of Goldsmith’s score. In his novella “Now And Forever…Somewhere A Band Is Playing” (William Morrow Company, 2007), Bradbury remarks that his adoration of Goldsmith’s score for “The Wind And The Lion” inspired him to compose a lengthy poem, which he later incorporated into the prologue for his story, “Somewhere A Band Is Playing.” Such is the mesmerizing power of art in any of its forms.

Goldsmith was delighted to have been asked to compose the music for First Knight. He felt at home in a colorful world of courageous warriors, fighting valiantly to preserve the honor and value of king, honor, and country. Damsels endangered by distress, and the noble lords who vanquished evil on their sweet behalf, was a concept that appealed deeply to the composer’s traditional Jewish upbringing and sensibilities. He was, at heart, a romantic. Indeed, Goldsmith’s agent at the time, Richard Kraft, comments in the liner notes of First Knight that Jerry “ was very excited when it seemed like he was going to get the job, and while he was working on it he was as happy as I’ve ever seen him.” Goldsmith himself remarked that “It’s more interesting for me to try and write music that gets inside people, and First Knight was perfect…it had all the romance and all that splendor.”

First Knight is, above all else, a deeply felt, passionate musical tapestry capturing an era of romanticism and heroic grandeur that, like visions of Tara, gallantry, and ladies fair, has sadly passed into history and, but for the flickering image on the silver screen in tribute to its memory, has gone with the wind. Zucker’s film offered a somewhat different view of the Arthurian legend and yet, in the end, is handsomely mounted by striking visualizations of Camelot, Sean Connery’s tortured dignity, and Jerry Goldsmith’s brilliant musical score. Rather appropriately, as remembered by album producer Bruce Botnik, “Sean Connery came up to Jerry at the premiere, gave him a big hug and told him that he loved the score and wanted his theme played whenever he walked into a room. Jerry said that it was one of the highest compliments he could ever have received.” This long day’s journey into Knight is deserving of inclusion in any collector’s recording itinerary.

MASADA

Masada (Intrada, 2 CD set), filmed as an epic mini-series for ABC Television in 1981, is yet another reverential, sacred commemoration of courage in the face of tyranny, a solemn testament to the remarkable heroism and sacrifice of a proud people confronting their own mortality in the face of slavery and religious oppression. Airing from April 5 thru April 8, 1981, this ambitious teleplay was estimated to have cost roughly twenty-three million dollars.

According to Intrada Records producer Douglass Fake, Goldsmith had sat with director Sydney Pollack during an airplane flight, during which the director discussed scouting locations in Israel for a television program based upon the story of Masada. Goldsmith, who had apparently never before sought out film projects, told Pollack “I’ve never done this before, but I’ve got to do this picture.” Universal Pictures was thrilled to have the distinguished composer on board for what was essentially a made for television movie, and dispatched the composer to The Holy Land in order to research the project. “It was very exciting because I did get to see and do things that the normal person wouldn’t get to do,” he later related. “It was just the emotional and historical impact of that story. Being Jewish, I feel very close to those subjects, as I did on QB VII, and being in Israel for the first time added to the excitement of it.” Goldsmith felt a special affinity for assigned director Boris Sagal, with whom he had worked on television programs as early as 1960. Though contracted to write the music for the entire four evening presentation, delays in production forced Goldsmith to exit his commitment after only half the series had been scored. Composer Morton Stevens, who shared assignments on NBC’s Thriller series with Goldsmith, finished the massive scoring assignment after Goldsmith was forced to leave due to overlapping film commitments.

What remains, however, is a deeply passionate salute by Goldsmith to the legend and ultimate tragedy of the mass suicide of more than nine hundred Jewish patriots, taking their own lives rather than submitting to forced enslavement by conquering Roman soldiers. Intrada has released a faithful two CD set of both soundtrack scores by Jerry Goldsmith and Morton Stevens, capturing the sweeping spectacle of an historic monument to human dignity and sacrifice.

80TH BIRTHDAY TRIBUTE

Robert Townson, the visionary producer behind Varese Sarabande Records has been responsible for more than one thousand recordings of motion picture music on his prestigious label, culminating with the definitive representation of Alex North’s brilliant score for Stanley Kubrick’s masterpiece, Spartacus (1960).

Having proudly assembled and hosted two previous live concerts for the Fimucite festival in Tenerife, Townson has created a special tribute to Jerry Goldsmith for the third installment of this spectacular performance series. Dedicated exclusively to the superb science fiction and fantasy scores composed by Goldsmith, this marvelous 80th Birthday Tribute Concert evening is being released both on DVD and on CD in a deluxe new package from Varese. The belated release of this ninety minute tribute to Goldsmith’s eightieth birthday features exciting symphony performances of such Goldsmith scores as Capricorn One, Total Recall, Poltergeist,The Swarm, The Illustrated Man, and The Final Conflict. The composer’s widow, Carol, makes a rare, special appearance during the program to accept a heartfelt tribute to her late husband. Filmed in 2009, with Mark Snow and Diego Navarro conducting The Tenerife Film Orchestra and Choir, this stunning latest release from Robert Townson and his remarkable label are merely the newest jewels in an ever expanding and sparkling musical crown.

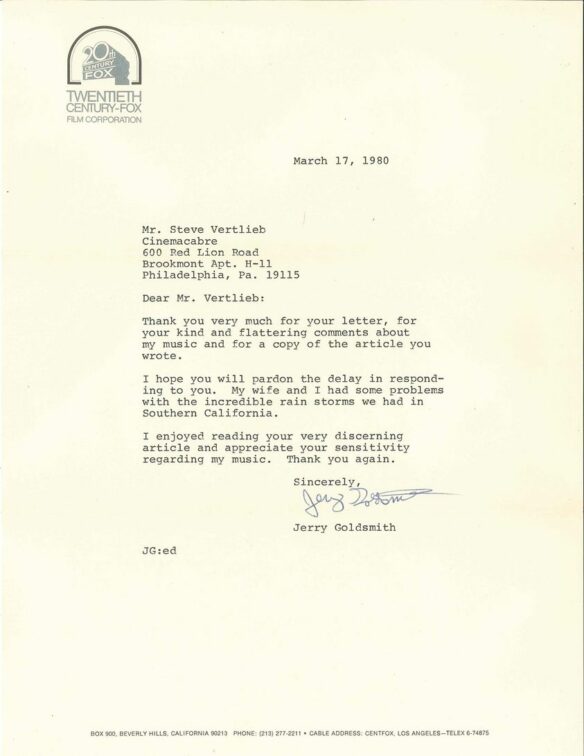

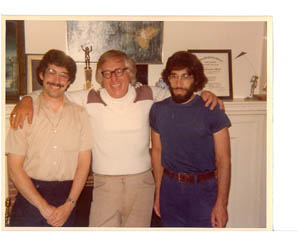

This is not my first attempt at chronicling this composer’s work in film. I was writing an article about Jerry Goldsmith’s music for cinema at Cinemacabre Magazine back in 1980. I had been writing a regular soundtrack column on the subject of film music for the magazine for several years, and decided that Jerry Goldsmith would make an interesting subject for a feature article. I did some research, and located his agent. I simply wanted to unearth some recent photographic material with which to illustrate the article, and tried to find some current stills. His agent at the time suggested that I telephone Jerry, and ask him directly whether he had any recent photographs that I might be able to utilize. The publicist gave me Jerry’s contact information, and I dialed his home telephone number, speaking briefly with the family housekeeper who informed me that the Goldsmiths were out for the evening. I left my name and telephone number with her, never expecting to receive a return call. Less than twenty-four hours later, however, the telephone in my apartment chimed, and the distinguished sounding caller identified himself as Jerry Goldsmith. Somewhat stunned and at a loss for any sense of verbal eloquence, I merely expressed my admiration for his music and asked if he had any stills that he might send me for the proposed article. He said that he had recently completed a new publicity photo shoot and that, as soon as the photographer sent him the “proofs,” he would send me some new material. True to his word, the photos arrived about a month later and I happily used them in my article.

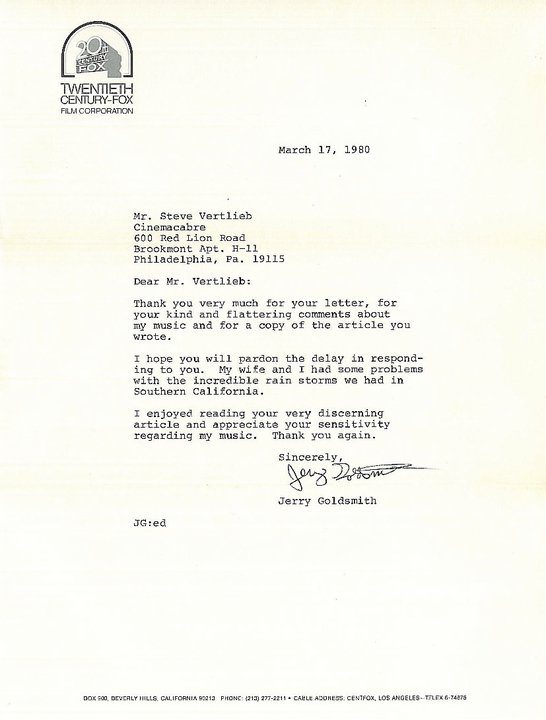

Shortly thereafter, I received the following communication from Jerry on stationary issued by the 20th Century Fox Music Department…

March 17th, 1980

Dear Mr. Vertlieb:

Thank you very for your letter, for your kind and flattering comments about my music and for a copy of the article you wrote.

I hope you will pardon the delay in responding to you. My wife and I had some problems with the incredible rain storms we had in Southern California.

I enjoyed reading your very discerning article and appreciate your sensitivity regarding my music. Thank you again.

Sincerely,

Jerry Goldsmith

From First Knight to last, Jerry Goldsmith was a class act.