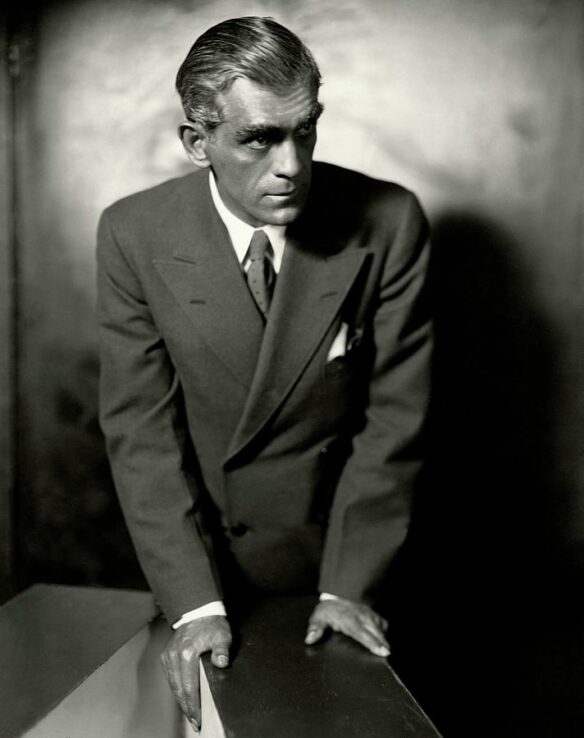

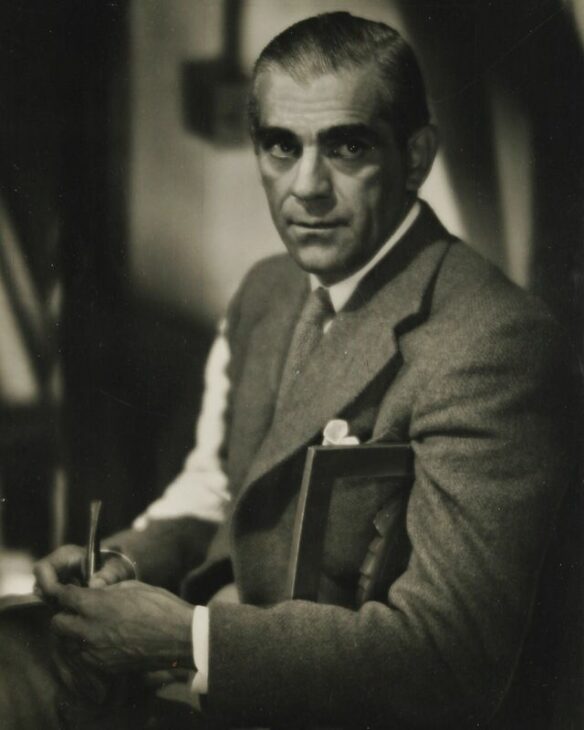

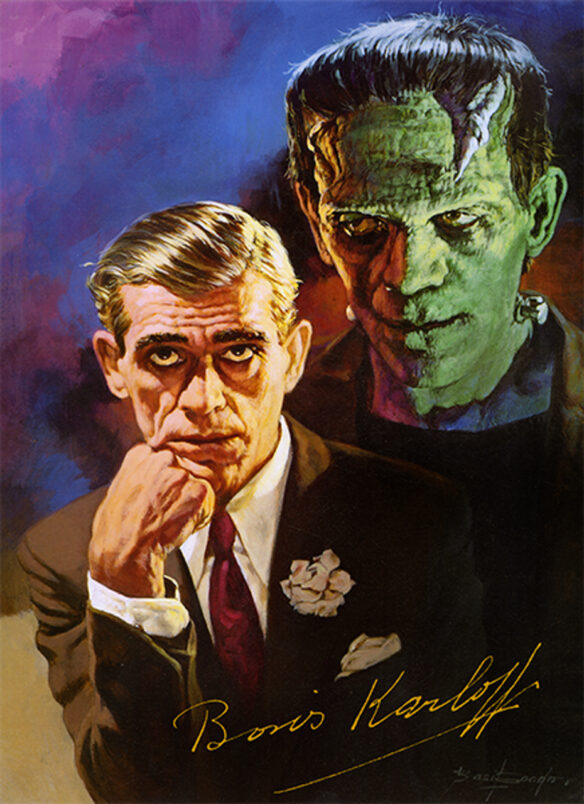

By Steve Vertlieb: Perhaps no other actor in the long, durable history of horror on the motion picture screen has been so closely identified with the genre as Boris Karloff. Yet, this “monstrous” presence was as famous for his gentle heart and kindness as he was for his screen persona.

That his very name can conjure goose bumps and chills to children, or adults that remember his films, so many years after his legend and ultimate passing is a tribute to the artist and the man. Born William Henry Pratt on November 23rd, 1887, at Camberwell in the South of London, he was the youngest member of a family that included eight sons and one daughter.

He spent his formative years at the family home on Forest Hill Road in Dulwich, which may have earned him his later reputation (with apologies to H.P. Lovecraft) as “The Dulwich Horror”. Young Billy never knew his father. Edward Pratt had worked for the Indian Salt Revenue Service and had virtually abandoned his family in far off England. Edward died when his son was still an infant and so Billy was raised by his mother, Eliza Sara (Millard) Pratt until her untimely passing. Thereafter, he was raised and sheltered by his brothers and his sister.

While all of Billy’s brothers had eventually followed in their father’s footsteps and entered the Diplomatic Corps, one had briefly flirted with the theatre and had performed on the stage. When his career seemed at a dead end, he too joined the Diplomatic Service but not before the seeds of performance had taken root within the heart of his baby brother.

W.H.P., as he liked to refer to himself, had been smitten by the proverbial acting bug and no amount of familial coercion could dissuade him from his chosen profession. By all accounts, the youngster was a kind, gentle boy who had little aptitude for, or interest in, the service. He was a dreamer with strikingly handsome features, and a commanding voice. While his brothers chastised him repeatedly for choosing such a disreputable career, rather than the honor of political service, Billy would not entertain any course but his own.

As a child, Billy performed each Christmas in plays staged by St. Mary Magdalene’s Church. Interestingly, his very first role was that of The Demon King in the pantomime Cinderella. It would not be the last time that he would play such a part.

By 1909 William had become obsessed with thoughts of a life in theatre, and read for every part that he could find. At twenty-two years of age, he announced his intention to leave home and pursue an actor’s life. The youth purchased a second-class steamer ticket for Montreal and, on May 7th, 1909, sailed from Liverpool to a new land filled, he believed, with opportunities for his chosen career.

Theatrical positions were difficult enough to obtain for a seasoned professional, but Billy had no real experience and so resorted to manual labor in order to eat. Ditch digging and laying track for the British Columbia Railway System paid some of the bills and afforded him a meager meal now and again. His brothers supported him when they could with economic care packages, but it wasn’t long before he had grown despondent.

Reading the classified ads one day in a local newspaper he stumbled upon a notice placed by the Ray Brandon Players in Kamloops, some two hundred fifty miles away, seeking an experienced character actor. He desperately wanted to apply for the position but realized that his name wasn’t remotely theatrical. He recalled a distant family branch on his mother’s side by the distinguished name of Karloff. For a first name he chose what he fancied might be construed as a dignified, professional Christian name…Boris. It seemed to jell, and so young Boris Karloff happily applied for the position with the company in faraway Kamloops.

Touring Canada

After his first performance as Hoffman, the banker, in playwright Ferenc Molnar’s The Devil it was obvious to everyone, including the actor, that he was not a professional. However, the manager of the troupe felt that Karloff had potential and allowed him to stay. For the next year he toured much of Western Canada with the company, playing largely villainous roles.

Early in 1912, however, Canada’s infamous cyclone hit the community, wiping out both the town and the resources of the small acting troupe. Karloff then joined the Harry St. Clair Players in Prince Albert, spending two years with the repertory company. They toured the Midwestern United States, but studiously avoided performing in large cities. When the actor grew tired of working only in strictly rural towns and communities he found work with another touring company, the Billie Bennett troupe. They were taking a production of The Virginian on the road and, among their destinations, was Los Angeles, California. Arriving in December, 1917, Boris Karloff had discovered Hollywood.

Karloff in Hollywood

Fame and fortune continued to elude the young actor, however, but he found enough manual labor and temporary work in theatrical stock companies to pay the bills. Several years passed before he received an invitation from an old friend, Alfred Aldrich, to join him for a chat. Aldrich suggested that his friend try to find work in the growing film industry. Karloff hit the bricks, and his persistence paid off in winning some extra work in the celluloid community.

Aldrich introduced Karloff to a film agent by the name of Al MacQuarrie. The agent found Boris a few days’ work as an extra on a Douglas Fairbanks film called His Majesty, The American. He portrayed a Mexican soldier, and often spoke of this as his motion picture debut. With a bit more confidence under his belt he began making the rounds of the local agencies, meeting Mabel Condon who was at once enthusiastic about his look and potential. She cast him in a small part in a film with Blanche Sweet. It wasn’t long before a more substantial role followed, once again, with Blanche Sweet.

In The Deadlier Sex, he played a French-Canadian trapper, a role he was to continue to play in his next half dozen assignments. By 1923, the industry’s fascination with French Canadians had dissipated, however, and the actor found himself out of a job.

The story goes that on one particularly dispirited afternoon, Karloff heard the repeated honking of a car following him out of the gates of the studio. The man in the car behind him was an actor he had met briefly on a variety of film sets, and who had taken a liking to the young performer. Lon Chaney emerged from his vehicle, asking the startled youngster “Don’t you recognize old friends, Boris?”

Chaney invited Karloff to ride with him for a time. They drove together for an hour, during which Chaney asked his youthful friend about his goals and dreams. Chaney told him: “The secret of success in Hollywood lies in being different from anyone else. Find something no one else can or will do, and they’ll begin to take notice of you. Hollywood is full of competent actors. What the screen truly needs is individuality.”

Though still continuing to act in minor parts within minor films, he managed to supplement his income by working as a truck driver. Driving a seventeen-ton rig, he was asked to deliver three hundred casks of cement. The cement had to be carried from the warehouse to his truck, driven twenty-seven miles, and then unloaded again. In later years his wife, Evelyn, recalled the incident as what may have been the beginning of his life-long battle with crippling back pain.

In 1926 Karloff found a provocative role in The Bells, in which he played a sinister mesmerist alongside Lionel Barrymore, who actually sketched out the bizarre Caligari make up for his young co-worker. Karloff worked with Barrymore again in his first sound film, The Unholy Night (1929) which the older actor directed.

One afternoon in 1930, Karloff strode up the stairs to the Actor’s Equity office in Los Angeles to check his mail. The girl at the front desk asked him if he was working. When he answered “no,” she told him that they were casting a local production of The Criminal Code at the Belasco Theatre. He won the part of a vicious convict named Galloway who stalks and murders a stool pigeon. The play was a success, and when Columbia Pictures announced plans to make a movie version of the story to be directed by Howard Hawks, starring Walter Huston as the prison warden, Karloff was signed to repeat his stage role. The film was released in 1931 and, with his characteristic short-cropped hair and menacing features, Karloff was a frightening sight to behold.

Karloff was working steadily now and was cast by director Michael Curtiz for a Svengali-themed opus called The Mad Genius, along with John Barrymore.

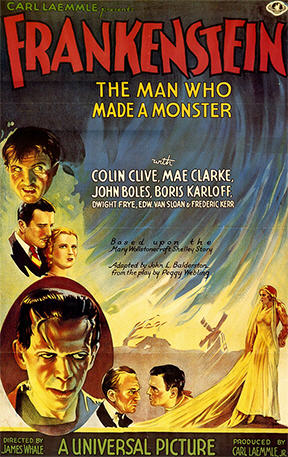

Frankenstein

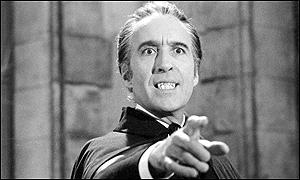

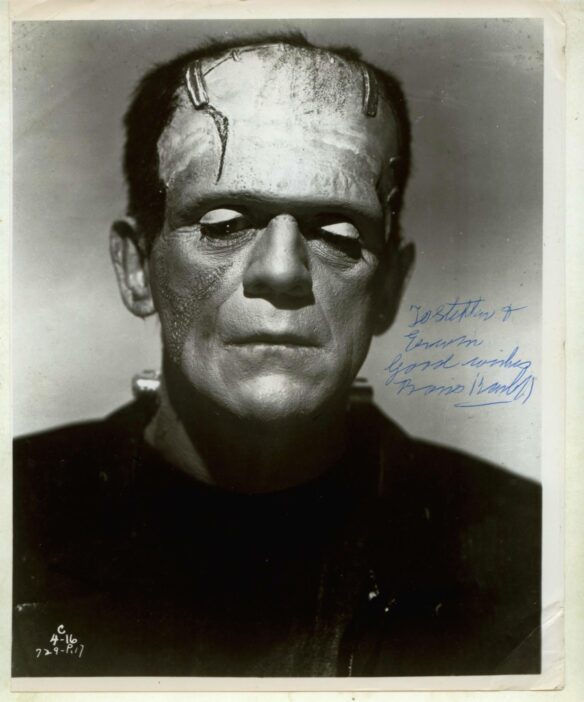

When Universal was preparing its production of Frankenstein, the part of the Creature had been offered to their new horror star, Bela Lugosi, but Lugosi turned the part down, fearing that his identity would be smothered in makeup. Lon Chaney had died unexpectedly and so the studio was left without a monster.

Director James Whale decided to take a chance on a fellow countryman, and relatively unknown actor for the part. Boris Karloff was given the role of a lifetime, and one that would forever change the course of his life.

Had Lugosi agreed to portray the “monster,” Robert Florey would have directed the film. When Lugosi declined the studio’s offer, Florey joined Lugosi on Universal’s adaptation of Poe’s Murders In The Rue Morgue.

Whale spotted Karloff having lunch in the studio commissary, and invited him to join his table. Whale commented later that “Karloff’s face fascinated me. I made drawings of his head, added sharp bony ridges where I imagined the skull might have joined. His physique was weaker than I could wish but that queer, penetrating personality of his, I felt, was more important than his shape which could easily be altered.”

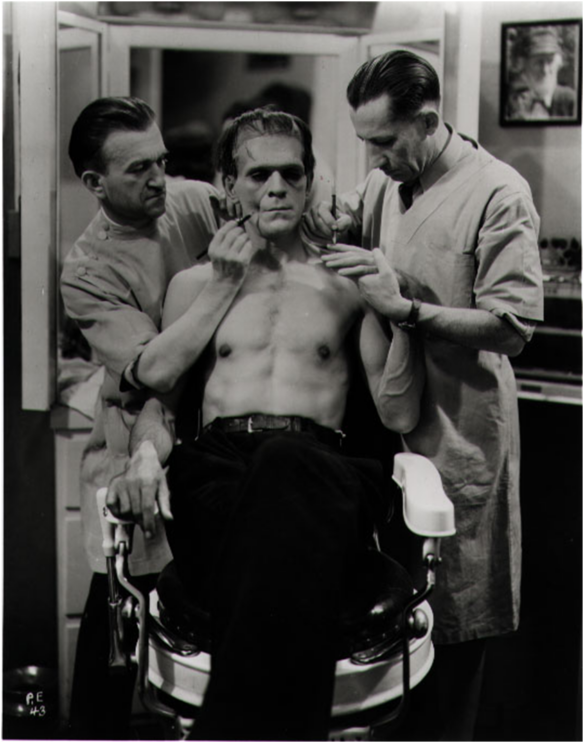

Karloff arrived at the studio each morning at five-thirty and sat for three and a half hours in the makeup chair. Universal’s resident genius, Jack Pierce, created the demented appearance of the creature, an unforgettably shocking visage of a gaunt, hollow being tormented on either side of death’s descending veil.

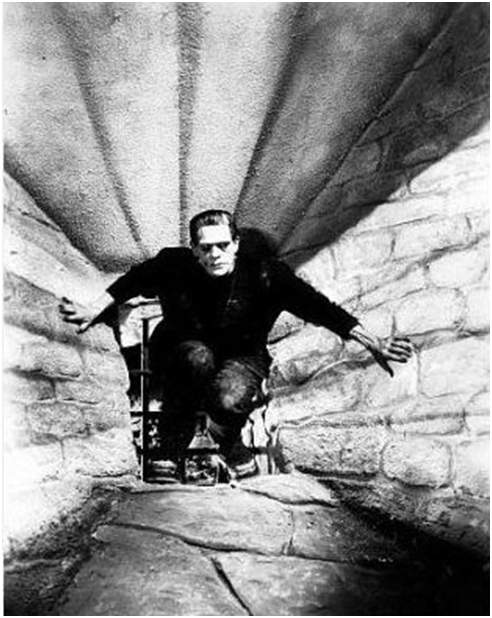

The first appearance of the “monster” in the premiered film had to have been unexpectedly shocking to theatergoers. Whale’s startling introduction of Karloff is as unforgettable as any moment in screen history, perversely duplicated eight years later by John Ford as John Wayne reached close-up immortality in Stagecoach. The technique, although more romantic, was nearly identical in its staging.

There was an eerie, nearly ethereal quality to Karloff’s gestures, as though he had actually returned from the grave. His desire to return remains a chilling evocation of a lost soul, condemned to wander the endless corridors of eternity. When Colin Clive opens the creaking gates of the rafters buried deep within the castle ceiling, sunlight burns deeply into the scarred facial tissue of the transposed creature. Hypnotically, without a will of its own, the “monster’s” arms reach up toward the source of the light, a queer marionette searching in unfathomed recognition for the creator of existence.

As the rafters slowly close, returning darkness to the room, the creature’s arms descend in dumb obedience as the light of eternity passes from his gaze, leaving him alone and desolate once more.

Frankenstein became an enormous success for the studio, and for its newest star whose name was not revealed until the final credits of the picture, and then only as KARLOFF.

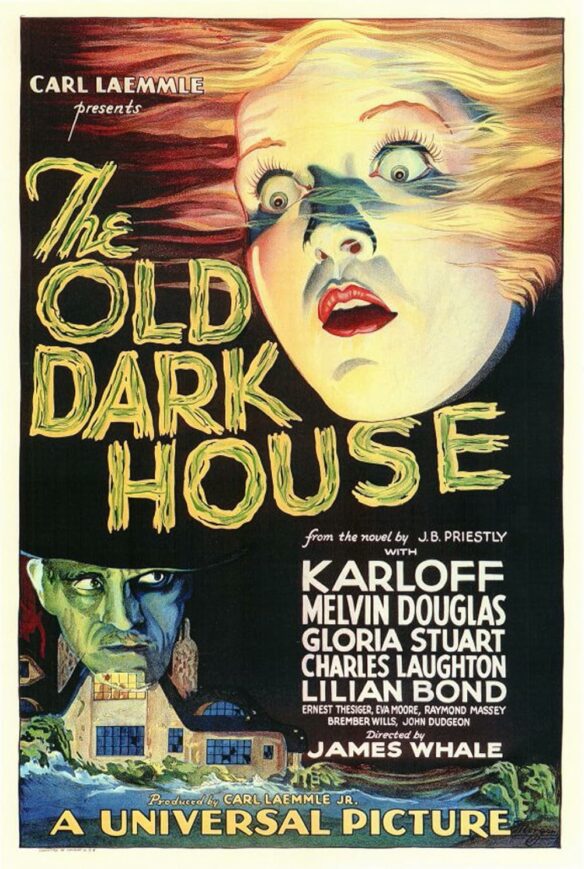

In 1932 Karloff earned a featured role in Howard Hawks’ classic Scarface starring Paul Muni. During the same year he was happily reunited with James Whale in the studio’s recreation of J.B. Priestly’s macabre comedy, The Old Dark House. With a wonderful cast comprised of Karloff, Melvyn Douglas, Charles Laughton, Raymond Massey, Ernest Thesiger and a young Gloria Stuart (later to star in James Cameron’s epic, Titanic), this quirky, eccentric version of Priestly’s Benighted remains a strange, delightful gem.

Universal decided to loan their new star to the prestigious Metro Goldwyn Mayer to play the coveted title role in Sax Rohmer’s exotic The Mask Of Fu Manchu. Wonderfully kinky, the film co-starred young Myrna Loy as the intoxicating, yet sadistic Fah Lo See, Fu Manchu’s sexually perverse daughter. Filmed prior to Hollywood’s infamous production code, the film joyously escaped the later scrutiny of The Hayes Office, and remains a fascinating example of pre-code extravagance.

Loy’s obvious excitation in ordering the flogging of her half naked captor, cowboy star Charles Starrett, is daring even by today’s standards: eyes open wide, nearly achieving an orgasm as the lash tears into his flesh with furiously increasing rapidity. Lavishly filmed and executed, The Mask Of Fu Manchu remains one of the most unique, original horror fantasies of the thirties and the definitive representation of Rohmer’s infamous villain.

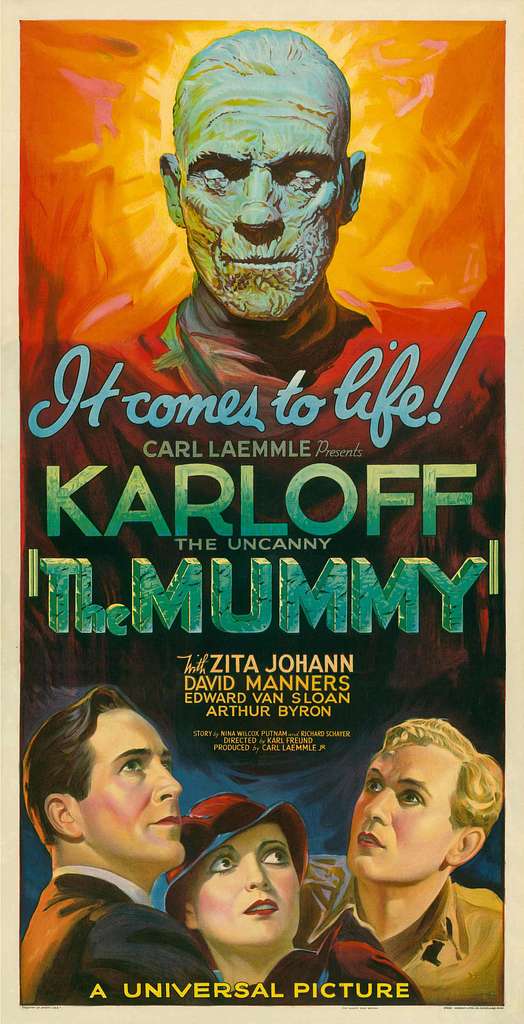

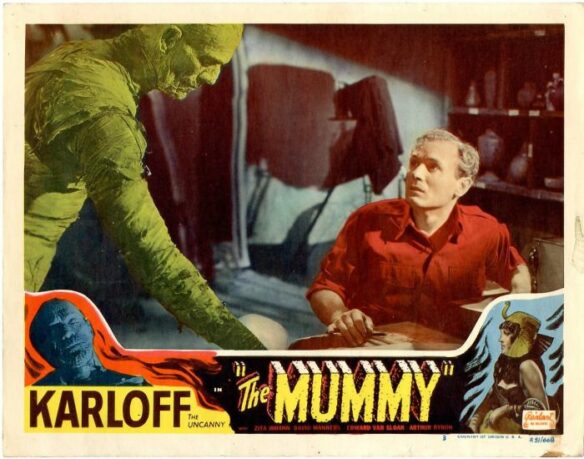

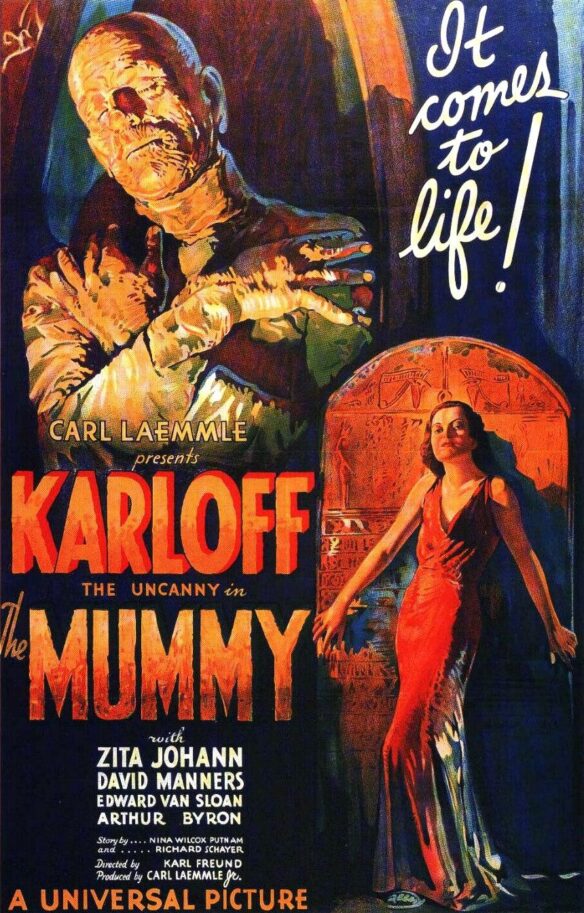

Karloff returned to Universal for one of his most memorable motion pictures, The Mummy.

Released for Christmas, 1932, it featured Karloff as Im Ho Tep, the resurrected incarnation of an ancient evil. Directed by Karl Freund, an emigre from Germany’s golden, expressionistic era, Freund had photographed Lugosi’s Dracula and would continue working in Hollywood well into the 1950s as principal cinematographer for television’s I Love Lucy. Noble Johnson, who one year later would appear as the native chief in King Kong, played “The Nubian,” Im Ho Tep’s servant, while Bramwell Fletcher created an indelible impression as the young archaeologist who unwittingly brings the withered mummy back to life.

Screaming at the sight of the living mummy, Fletcher lapses quickly into mental incompetence, muttering “He…he went for a little walk. You should have seen his face.”

Fletcher was active for many years in both films and the theatrical stage, replacing Rex Harrison on Broadway as Henry Higgins in My Fair Lady. During the late sixties, he starred as writer George Bernard Shaw in a one-man show that toured the U.S. It was during a stop in Atlantic City, New Jersey, that this writer had the good fortune to meet and befriend the actor — a relationship that continued until his passing some years later.

The Mummy is rich in its atmospheric portrayal of an ageless soul, reaching out beyond centuries to reclaim a forbidden, reincarnated love. It remains one of Boris Karloff’s signature portrayals. His eyes literally burn with the intensity of one who has walked the corridors of time in search of his forbidden destiny. “Karloff, The Uncanny,” had been resurrected, along with the rotting flesh of the mummy he came to personify.

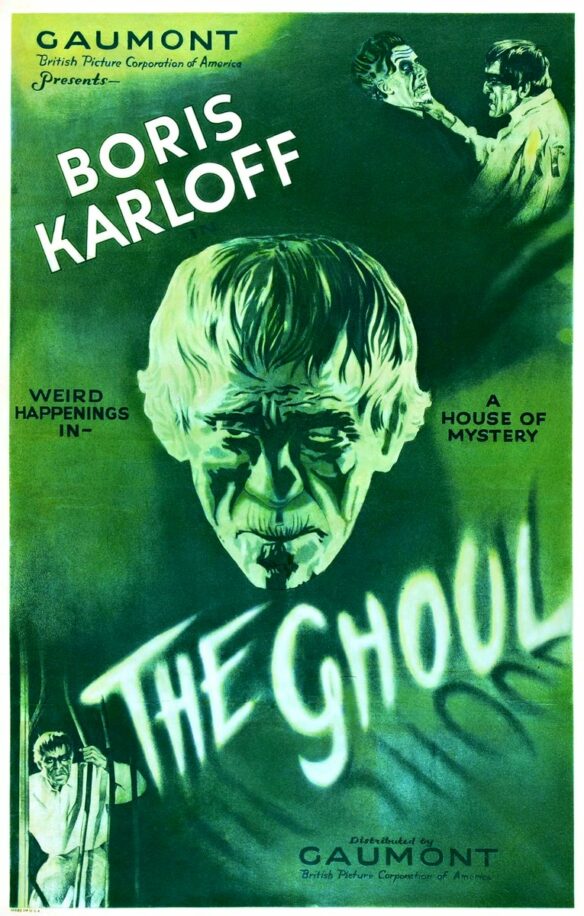

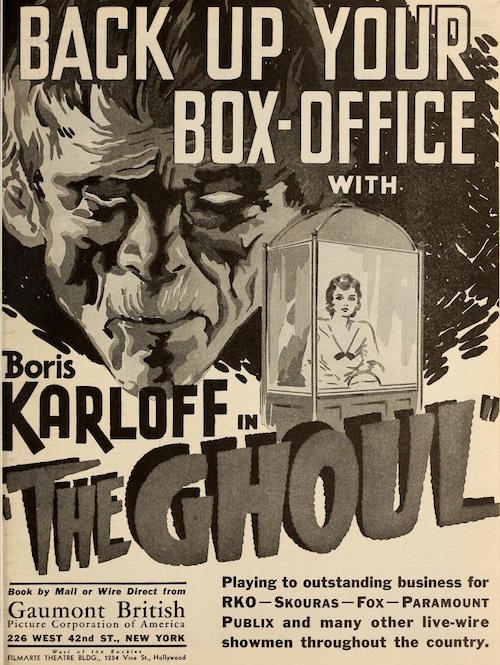

In 1933 Karloff returned to his native England in order to star in the brooding Gaumont British presentation of The Ghoul, based upon both the novel and play written by Dr. Frank King. Recently restored and rediscovered by an entirely new generation, the picture co-starred Cedric Hardwicke and Ernest Thesiger and is, in its newly discovered form, a revelation.

Karloff moved over to RKO Radio for the 1934 John Ford production, The Lost Patrol, in which he portrayed a religious fanatic gone mad in the Mesopotamian desert. It is an impressive, impassioned performance by an actor finding and exploring his considerable range at long last.

Karloff next co-starred, along with George Arliss, as the anti-semitic Prussian ambassador, Baron Ledrantz, in Alfred Werker’s The House of Rothschild for United Artists.

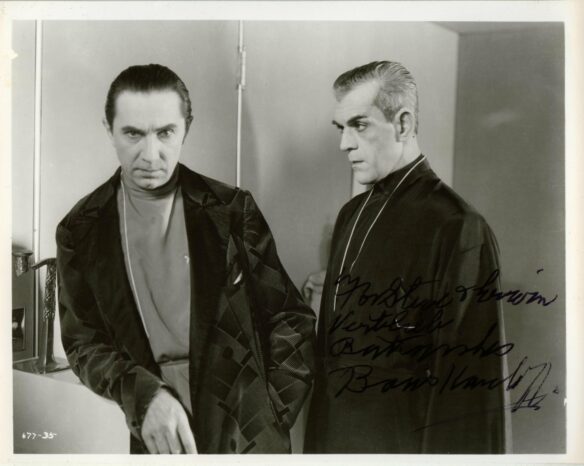

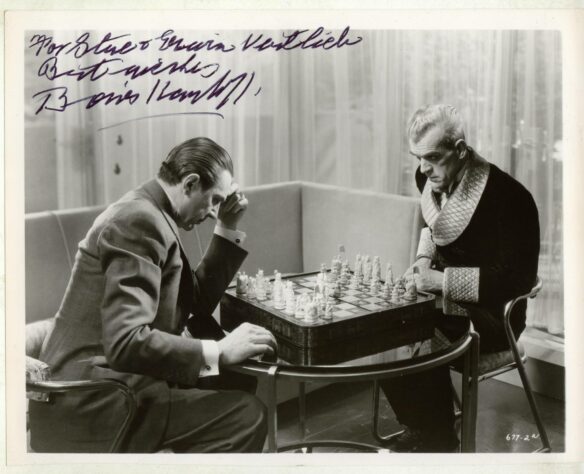

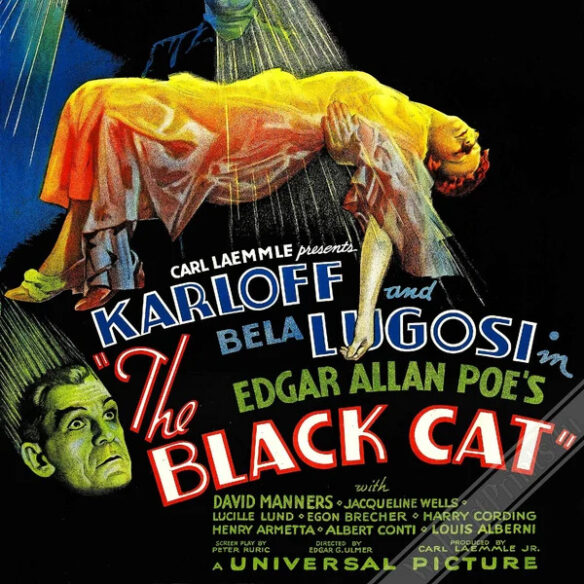

In May of 1934 Universal released their next major entry in the burgeoning Boris Karloff franchise. The Black Cat, directed by Edward G. Ulmer, became the first motion picture to pair the studio’s reigning “Titans Of Terror.” Karloff co-starred with Bela Lugosi in this fabulous tale of Teutonic adversaries in a war of nerves.

In the restored castle of the infamous traitor, Hjalmar Poelzig (Karloff)…built atop the graves of the countrymen he betrayed…comes his former friend, Dr. Vitus Verdegast (Lugosi), seeking vengeance after returning from a fifteen-year incarceration. Engineer Poelzig had stolen his wife, then married his daughter, reigning over the broken battlements of a decaying fort in which thousands had perished.

Smugly assembling a devil-worshipping cult within the walls of his blood-soaked castle, Poelzig is the embodiment of evil. A crazed genius and architectural futurist, he has designed an art deco palace worthy of the Wright Stuff.

To the somber strains of Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony, Verdegast plots his horrifying revenge, flaying the flesh from the shackled body of his host, bit by agonizing bit.

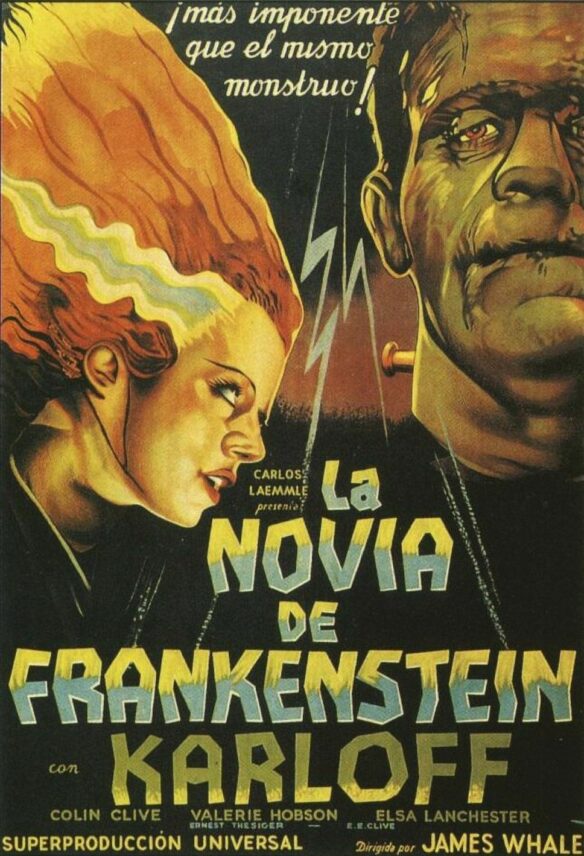

One year later, in May of 1935, Universal unveiled its masterpiece. After the release of Frankenstein in 1931 the studio had tried to persuade both Karloff and James Whale to film another story about the “monster.” Whale had no desire to repeat himself unless the treatment was sufficiently bizarre to warrant his attention. With a screenplay by William Hurlbut and John L. Balderston, and a cast that included Boris Karloff, Colin Clive, Valerie Hobson, Elsa Lanchester, Dwight Frye, Una O’Connor, O.P. Heggie and the astonishing Ernest Thesiger as the demented Dr. Pretorious, Whale delivered perhaps the greatest horror film of the decade and easily the most critically acclaimed rendition of Mary Shelley’s novel ever released.

The Bride of Frankenstein remains a work of sheer genius, a brilliantly conceived and realized take on loneliness, vanity, and madness. The cast of British character actors is simply superb, featuring the blatantly over the top, overtly gay, comic performance of Ernest Thesiger as the devil to Colin Clive’s Daniel Webster.

As thrilling and hilarious as the film often is, it also conceived one of the most moving and tragic film sequences of the thirties. Hounded and tormented by an ignorant mob of peasants, Frankenstein’s haunted creature is chased mercilessly into the forests of the night, where he stumbles upon the isolated cabin of a bearded blind man. Since the hermit cannot see the shocking features of his unannounced guest, he does not fear his nightmarish visage.

Attempting to communicate with the “monster,” he realizes that his mute guest is as helpless and physically impaired as himself. A bond of mutual trust is formed by society’s outcasts, and both reach out in kind for the opportunity to share a moment of tenderness and human compassion.

As the blind hermit offers his guest a hot meal by the fire he tells his newfound companion that they must have been brought together by fate. So taken is the creature by the hermit’s selfless spirit and gentle kindness that, as the strains of Ave Maria caress his weary heart, this relic from a world of corpses begins to convulse in tragic sobs. It is a heart wrenching sequence, interrupted all too quickly by the violent intrusion of John Carradine as an ignorant woodsman who sees only the ugliness, rather than the inner beauty, of the hunted beast.

Later in the film, when Frankenstein’s creation realizes that even his bride, another artificially resuscitated corpse, cannot bear to be touched by him, he bitterly sheds a final tear before blowing the laboratory and its deformed inhabitants to bits. Franz Waxman’s exhilarating original musical score for the film remains one of its greatest pleasures. Utilized by Universal in countless other productions, most notably in the classic Buster Crabbe serial, Flash Gordon’s Trip To Mars (1938), this symphony fantastique remains among the greatest, most influential scores ever composed for the motion picture screen and is an astonishingly eloquent tribute to a screen masterwork.

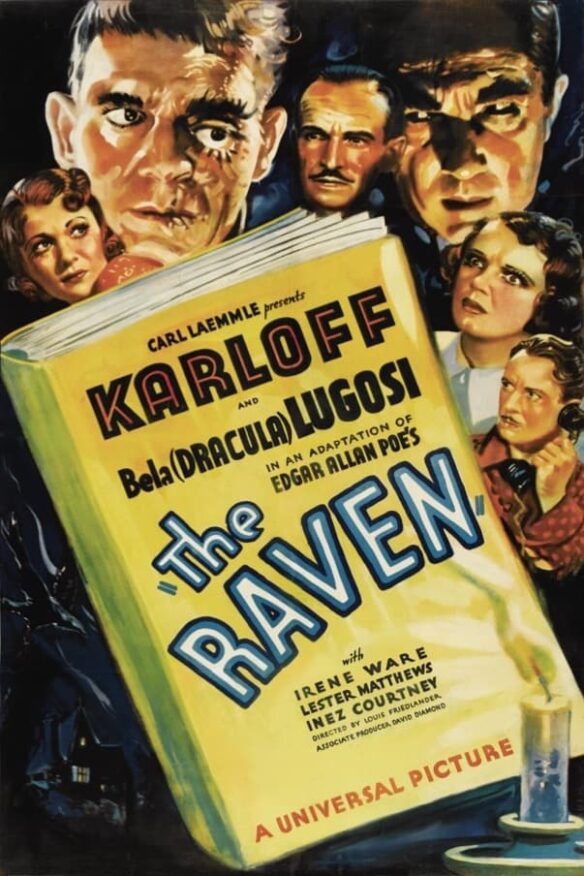

In July of 1935 Karloff starred as twin brothers, one kind and one evil, in The Black Room for Columbia. Later that same month Universal released the second of the Karloff/Lugosi pairings. Suggested by the work of Edgar Allan Poe, The Raven featured Karloff and Lugosi, respectively, as a criminal badly in need of plastic surgery and a brilliant, if mentally unstable, surgeon who deliberately distorts his face in order to bend him to his nefarious will. Karloff, as convict Edmund Bateman, is oddly touching as the flawed and fallen soul, while Lugosi handily steals the show in a bravura performance worthy of the Barrymores. Shifting the balance of power from the graphic finale of The Black Cat to that of The Raven, Karloff locks Lugosi within a deadly chamber in which the proverbial mad doctor is crushed, screaming, to his death.

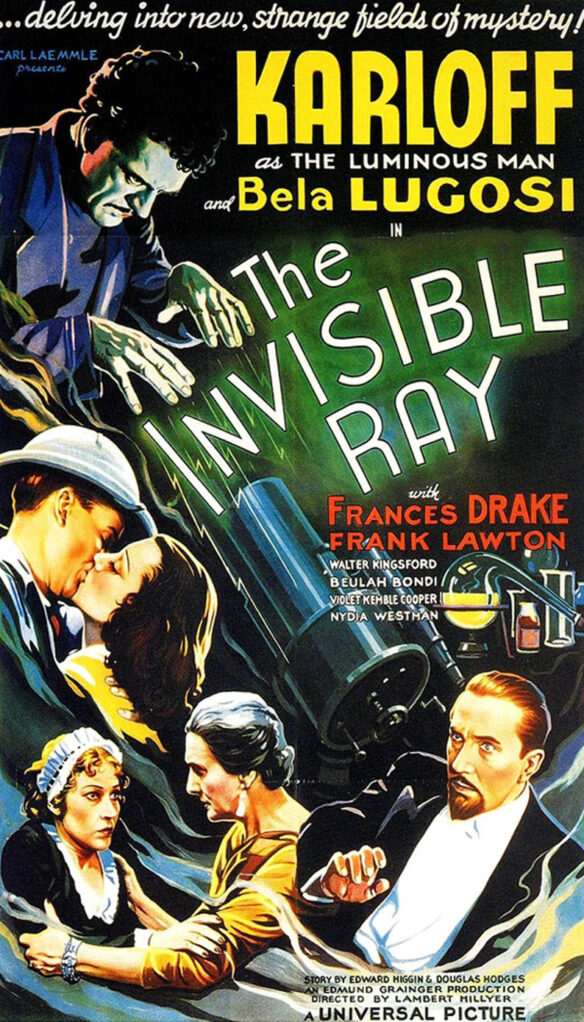

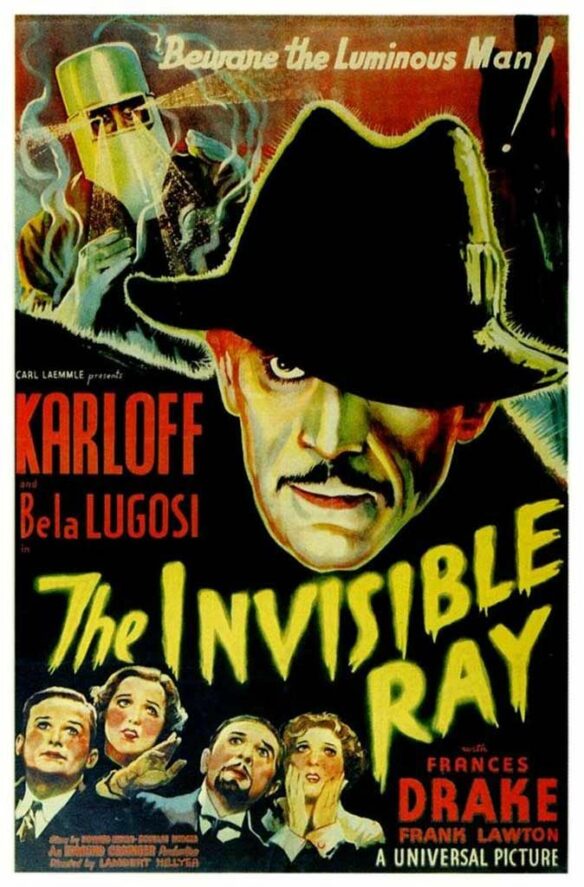

The rarely seen, imaginative science fiction melodrama, The Invisible Ray, quickly followed in January, 1936, starring Karloff as the tragically misunderstood Dr. Janos Rukh whose noble experiments with Radium X are coveted and stolen by jealous contemporaries, while his young wife (the lovely Frances Drake, Peter Lorre’s vision of lust and perversion in MGM’s Mad Love – 1935) is similarly unhinged from his burning sphere by a more openly attentive suitor, Frank Lawton (A doomed passenger aboard S.S. Titanic in A Night To Remember (1958).

Lost to humanity and to himself, Rukh is at last consumed by the very radium that has poisoned his mind and his body. When the mother who had given him birth (Violet Kemble Cooper) smashes the last remaining antidote from his fingers with her cane, Rukh resigns himself to his bitter fate, an atomic meltdown of his cells before the grieving eyes of his parent. While this was the third pairing by the studio of arch horror rivals, Karloff and Lugosi, the latter’s part was a relatively minor, unsympathetic role, doing little to enhance his already fading stature.

Karloff often marveled at his friend and colleague’s unfathomable sense of business comprehension, frequently moving from a starring role in a major production to a minor characterization in a mediocre film. While Karloff’s theatrical instincts were usually intelligently thought out and wise, Lugosi’s choices were ill timed and self-destructive. They eventually destroyed him.

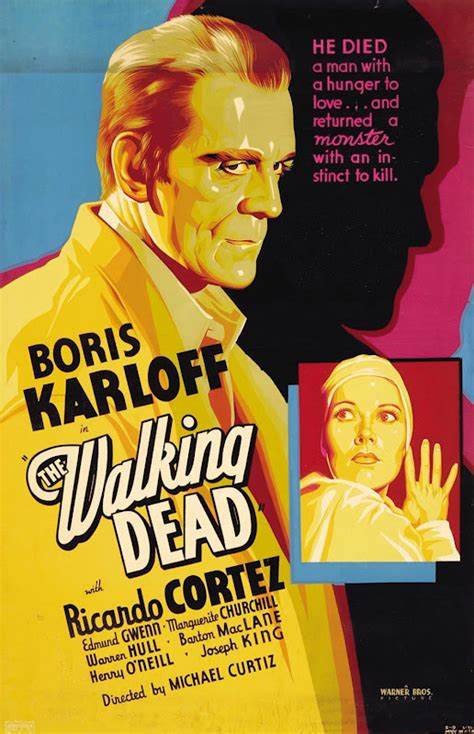

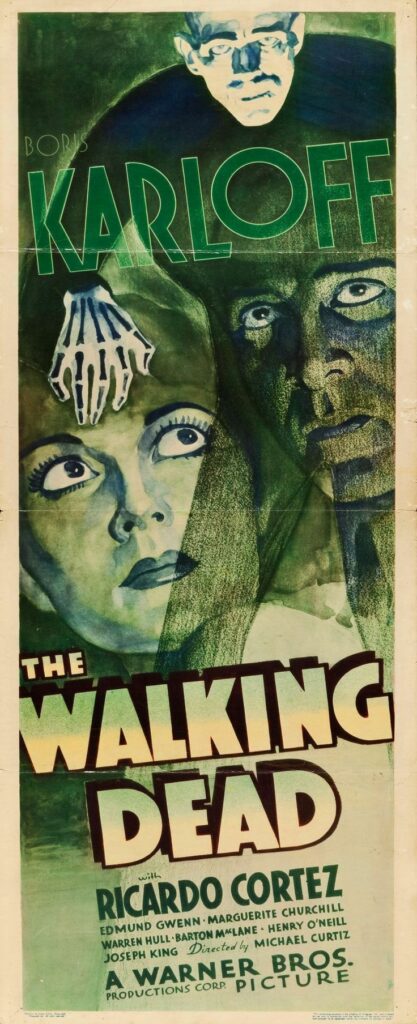

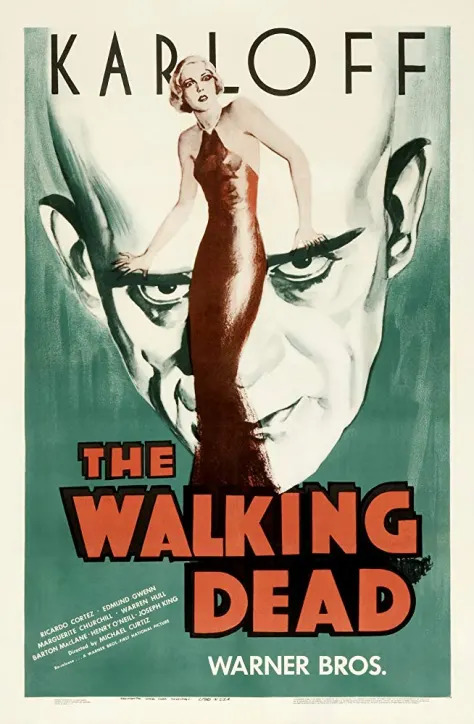

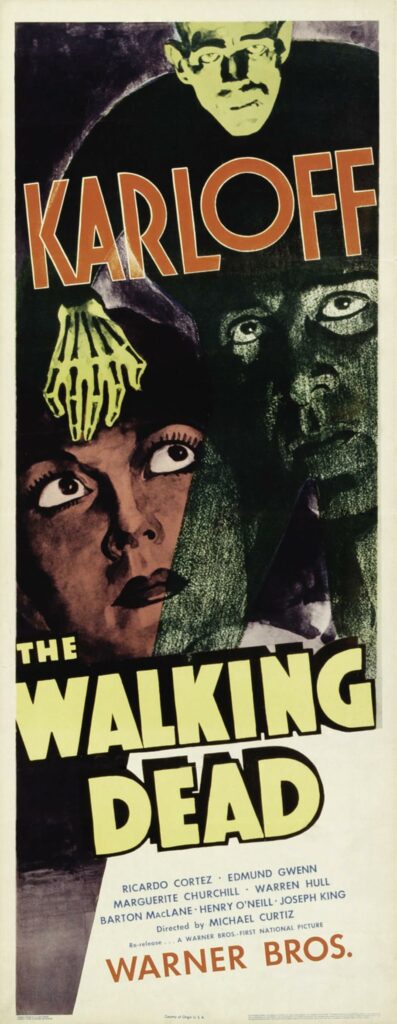

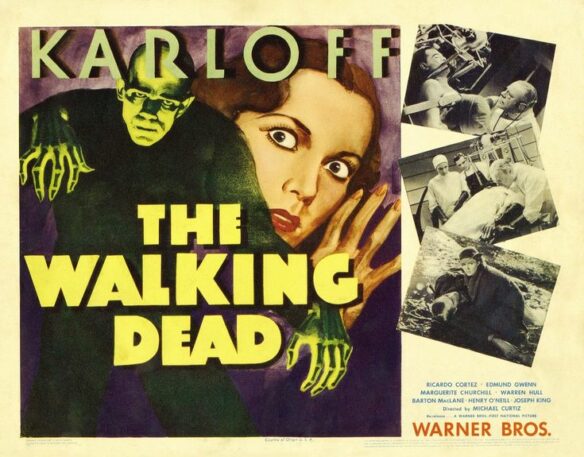

In March, 1936, Karloff starred in a seldom seen, yet deeply affecting film entitled The Walking Dead. He played John Ellman, an ex-convict wrongly executed for a murder he didn’t commit. When a kindly scientist (Edmund Gwenn of Them! fame) experiments on his corpse, bringing him back to “life,” Ellman seems to float between this world and the next. His hair has been streaked white, his eyes reflect the trauma of a soul lost between two worlds and, when he avenges his own death by killing those who accused him falsely, his gate is strangely reminiscent of Frankenstein’s “monster.” In the end, dying of gunshot wounds, he suggests that the doctor leave the dead to their inevitable fate.

Karloff returned to his native England once more to film The Man Who Lived Again for Gaumont British. This most satisfying production appeared lost for many years, resurfacing recently on home video and DVD in a pristine transfer. Co-starring Anna Lee and John Loder, the film concerns a brilliant scientist able to transfer the mind of one man into the body of another. Scorned and ridiculed by his jealous colleagues, Dr. Laurience (Karloff) succeeds in his mad experiments, finally attempting to transfer his own persona into the body of a much younger man, thereby extending his own life and winning the heart of his female assistant (Lee). The process is reversed just in the nick of time as Karloff perishes, taking his secrets with him to the grave.

In January 1937, Karloff appeared as an operatic villain for 20th Century Fox in the delightful Charlie Chan At The Opera, starring the gifted Warner Oland as the screen’s original Asian detective. (Oland also played Al Jolson’s Cantor father in The Jazz Singer, and the werewolf who infects scientist Henry Hull in The Werewolf Of London).

In January 1939, Universal Pictures released its third and final Frankenstein opus starring Karloff as the “monster.”

Universal had hoped to cash in on the success of their tepid, musical remake of The Phantom Of The Opera by casting its star, Susanna Foster, in an even more tepid clone entitled The Climax. Karloff stepped in for Claude Rains, who had already died in the earlier film, as a physician who tries to hypnotize Foster into believing that she cannot sing. It seems that the good doctor had already murdered his wife because her operatic career had come between them. Now, believing that the younger woman’s voice is the reincarnated embodiment of his wife, he sets out to prevent the tragedy from occurring again. While Karloff was as effective as ever, the scripting and music were hopelessly lame.

Knee-deep in the midst of its second official horror cycle, Universal hit upon the idea of combining its monsters in a horrific succession of malevolent Grand Hotel like ensembles, featuring all-star casts from its own haunted castle of contract players. House Of Frankenstein was released in December of 1944 but, while the erstwhile cast included Karloff, he would never again portray the “monster” on the silver screen. Rather, he played yet another in a long line of delectably mad doctors.

The release of Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Body Snatcher in March 1945 was another matter entirely, however. Produced by Val Lewton and directed by Robert Wise, the RKO release was a sober, adult look at the real-life crime of grave robbing to supply physicians with bodies for experimentation. Karloff played a ruthless practitioner of the trade, while Henry Daniell delivered the performance of his career as the tormented doctor willing to pay any price for a fresh corpse, caring little for the circumstances under which they arrived at his laboratory door. Bela Lugosi appeared in a decidedly minor role as a greedy servant attempting to blackmail the grave robber. It was the last time that the two would ever appear together on screen.

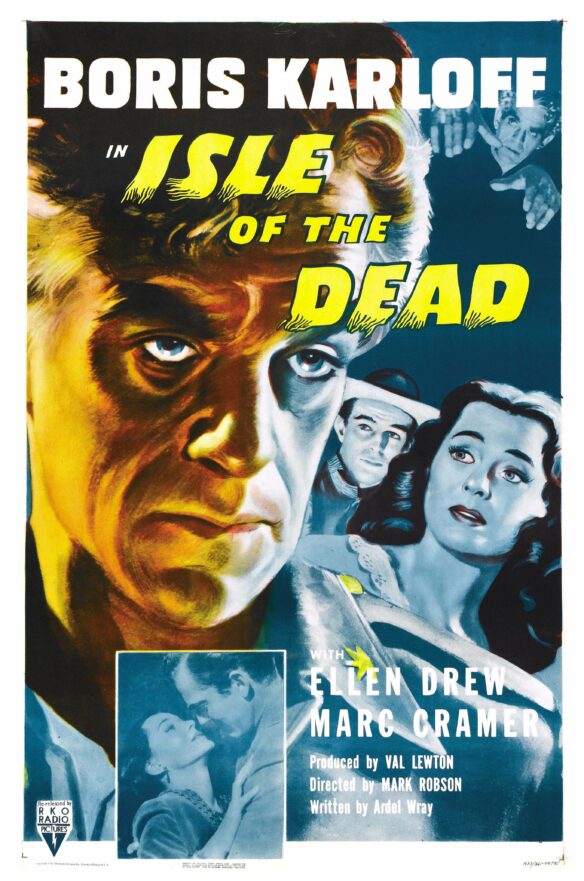

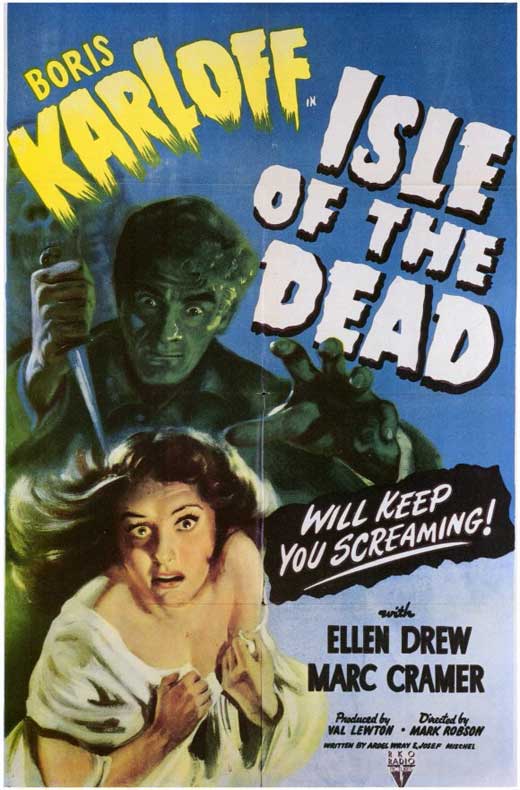

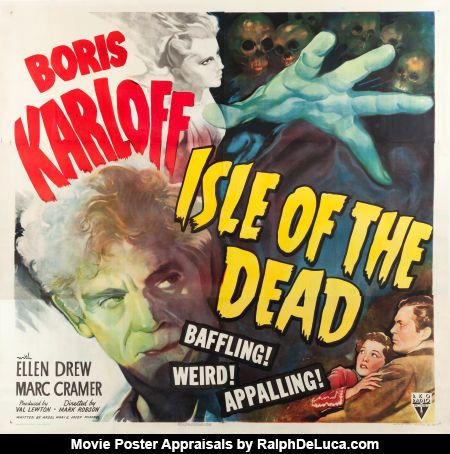

Lewton followed The Body Snatcher with an even more atmospheric production, Isle of the Dead, in which Karloff starred as General Pherides, driven to madness by superstition, intent on the spiritual destruction of an innocent girl he has come to believe is a vampire.

Filmed on a virtual shoestring, the Lewton productions quickly attained a well-deserved reputation for richly evocative imagery, favoring brooding shadows and imaginative cinematography above wasteful spending and extravagance.

Bedlam followed in May 1946, pairing Karloff with Anna Lee once again, in a story of the infamous mental institution of the eighteenth century. On a decidedly lighter note, Karloff returned to haunt the dreams of the insane, but lovable Danny Kaye in James Thurber’s The Secret Life of Walter Mitty, released by RKO in September 1947. The film was a smash comedy hit for the studio and for its esteemed producer, Samuel Goldwyn.

Karloff would revert to his earliest theatrical experience, playing Indians for Cecil B. DeMille in Unconquered at Paramount, and in Tap Roots for George Marshall at Universal in 1947 and 1948, respectively. Playfully poking fun at his ghoulish persona, Karloff joined Bud Abbott and Lou Costello in two theatrical outings at Universal. Abbott and Costello Meet the Killer, Boris Karloff was released in August 1949, while Abbott and Costello Meet Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde saw its release in August 1953. Both films were highly entertaining, and Karloff was chillingly effective as Dr. Henry Jekyll, as well as his monstrous alter ego, in the latter film.

Tiring of restrictive type casting in largely mediocre films, Karloff returned to the stage in 1950, starring on Broadway as both Father and the dastardly pirate, Captain Hook, in the acclaimed musical revival of J.M. Barrie’s fantasy, Peter Pan. The lovely Jean Arthur (Mr. Smith Goes To Washington and Shane) took flight from him as the enchanted boy who could fly, while composer Leonard Bernstein supplied the first-rate score. The production was a triumph for Karloff, who delighted in signing autographs for, and shaking hands with, star struck children after each joyous performance.

In 1952 the actor and his wife returned to England where he starred in a short-lived television series called Colonel March of Scotland Yard. Returning to the Broadway stage in 1955 to portray the sympathetic Bishop Cauchon in Jean Anouilh’s The Lark, Karloff regarded the production as the highlight of his long career. Julie Harris was his co-star as Joan of Arc in the celebrated play, recreated for live television in 1957 with Karloff, Harris and much of the original New York company intact.

Karloff had begun his television appearances in 1949 with a thirteen-week horror series for ABC called Starring Boris Karloff. Throughout the 1950s and 60s, Karloff was a familiar face to viewers. He reprised his starring role as Jonathan Brewster in Arsenic and Old Lace for the CBS drama series, Best of Broadway, on January 5th, 1955. Tony Randall co-starred as his befuddled younger brother.

Then, on November 6th, 1958, CBS presented a production of Heart of Darkness by Karloff’s favorite author, Joseph Conrad. The production co-starred Roddy McDowell as the man sent to find and “neutralize” a mad white man ruling a native community in the thick of the jungle. Heart of Darkness had been planned as a motion picture in 1940 by Orson Welles as his entry into the cinematic arena. He put the project aside in favor of a story based upon the life of newspaper publisher, William Randolph Hearst, titled Citizen Kane. Francis Ford Coppola finally filmed it in 1979 as Apocalypse Now for Paramount. While Marlon Brando played the part of Kurtz in the motion picture, it was Boris Karloff who starred as the mad Kurtz in the prestigious Playhouse 90 production in 1958.

Karloff was well known as a genuinely kind and gentle soul off the screen. He was also a deeply generous man, whose humility and shyness prevented any public recognition for his numerous acts of charity. That all changed on the night of November 13th, 1958, when host Ralph Edwards and an audience of millions witnessed the life and times of this very private gentleman unveiled on live television as a shocked, uncomfortable Boris Karloff became the latest subject of the popular television series, This Is Your Life.

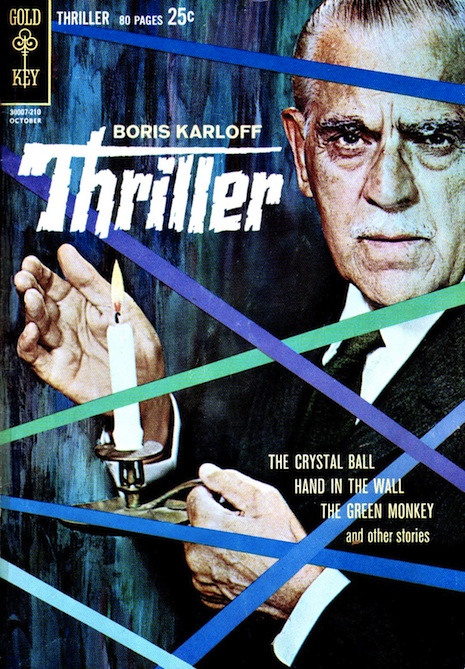

Karloff continued to act on the small screen and, on September 13th, 1960, he presided over the premiere and continuing run of a milestone in television history. This was the night that saw the beginning of a new NBC series entitled Thriller. Karloff hosted all of the episodes in its two year run, and acted in many of its teleplays.

In nearly sixty years of commercial television history, no other program so effectively realized the enormous potential of cinematic horror. That this black and white hour of weekly television so perfectly captured the unimagined terror and literacy of some of the greatest works in modern horror literature is an enduring testament to the power and legacy of Boris Karloff’s Thriller. The late Robert Bloch, who contributed many of the program’s most disturbing chapters (“The Hungry Glass”, “The Cheaters”, “The Grim Reaper”), reminisced happily about his excitement and pride in having been so closely associated with the legendary series shortly before his passing. Sadly, the world of weekly television has seen nothing approaching the quality and integrity of this nightmarish series either before or since its remarkable, gothic inception.

In 1962, Karloff hosted a weekly series of one-hour science fiction stories, Out of This World, produced by BBC Television in England. Then, on October 26th, CBS Television aired its special Halloween episode of the beloved series, Route 66. “Lizard’s Leg and Owlet’s Wing” concerned series stars Martin Milner and George Maharis encountering a small “convention” of horror actors, attempting to resurrect the ailing genre, by inspiring fear amongst a coterie of young, female executives. As guest stars Boris Karloff, Lon Chaney, Jr. and Peter Lorre (joined by Martita Hunt from Hammer’s Brides of Dracula) stalked the unsuspecting corridors of a local motel in full costume and theatrical persona, women fainted innocently away as the boys and their devoted following of millions of smiling viewers looked on in blissful remembrance.

Chaney donned his Wolfman mask and clothing, while Boris Karloff, the elder statesman of fantasy and horror, became the Frankenstein “monster” for one last moment lost in time.

In 1965 Karloff frightened timid librarian, Carol Burnett, in a painfully funny sketch for The Entertainers on CBS. In 1966 he had enormous fun playing a villain in drag for an episode of the NBC series, The Girl From U.N.C.L.E. in “The Mother Muffin Affair”. On December 18th, 1966, Karloff created yet another landmark in his long, distinguished career-that of the voice of the crotchety Grinch in Chuck Jones’ How The Grinch Stole Christmas for CBS. The Dr. Seuss classic remains a perennial holiday event, and won Karloff a Grammy for his spoken narration on the recorded album.

In February 1967, Karloff guest starred on the popular NBC television series, I Spy, starring Robert Culp and Bill Cosby. He played the sweetly befuddled Don Ernesto Silvando, pursuing the magically eternal quest of Don Quixote.

On screen, a new generation of children was discovering the legend of Boris Karloff.

In 1963 he appeared with friends, Vincent Price, Peter Lorre and a youthful actor named Jack Nicholson in Roger Corman’s delectable horror satire, The Raven. Karloff, the traditionalist, knew his lines and never varied from them. While he counted on others sticking to the script, and feeding him his cues, Price and Lorre were more adept at improvising and ad-libbing. After one particularly lengthy rant by Lorre, Karloff rested his chin upon his fist and asked, forlornly, “Are you quite through, Peter?”

In 1963, this time under the direction of master director, Jacques Tourneur, Karloff worked once again for American International in a brilliant effort titled Comedy of Terrors.

Reunited once more with Vincent Price, Peter Lorre, and Basil Rathbone, this comedic gem generated generous box office, as well as laughter.

Karloff’s next project for American International release was the Mario Bava classic, Black Sabbath, a truly frightening terror trilogy in which the wonderful actor played a vampire with bone chilling intensity. The Wurdelak, in 1964, would become his final, pure horror performance.

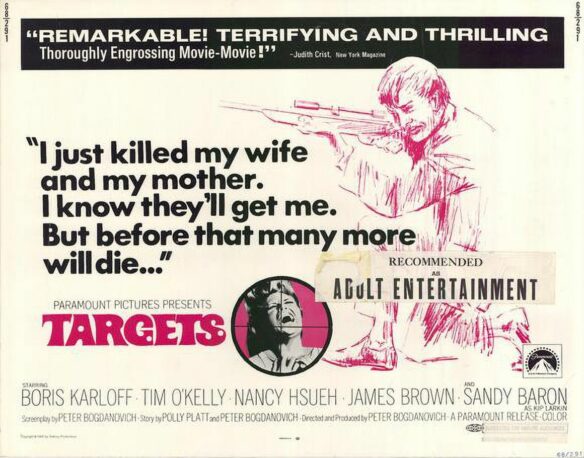

While Karloff continued working, by this time physically impaired and infirm, often performing from a wheelchair or with a cane, his last involvement of consequence came in 1968 with the Paramount release of a critically acclaimed “sleeper” hit called Targets.

Directed by fledgling artist, Peter Bogdanovich, and co-starring the director in a leading role, Targets was a profoundly disturbing study of a young sniper holding a small Midwestern community, deep in the bible belt, terrifyingly at bay.

The celebrated subplot concerned the philosophical dilemma of creating fanciful horrors on the screen, while graphic, troubling reality was eclipsing the superficiality so tiredly repeated by Hollywood.

Karloff co-starred, essentially as himself, an aged horror star named Byron Orlok, who wants simply to retire from the imagined horrors of a faded genre, only to come shockingly to grips with the depravity and genuine terror found on America’s streets. Bogdanovich’s first film as a director won praise from critics and audiences throughout the world community, and won its elder star the best, most respectful notices of his later career. While he went on to make several more mediocre films before his passing, Karloff regarded Targets as his final film.

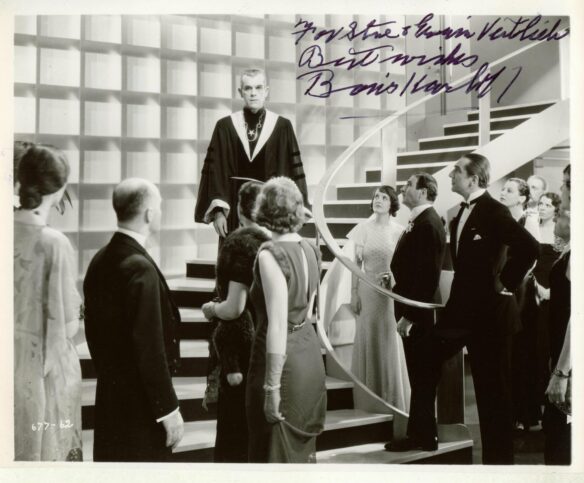

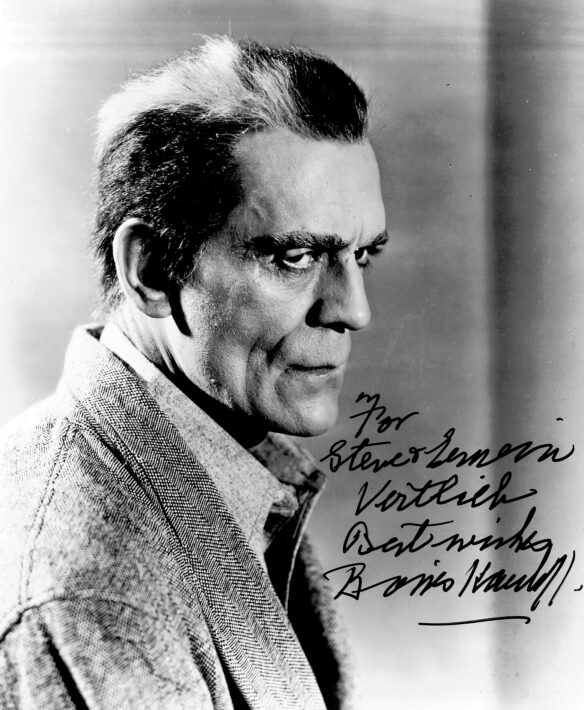

Somewhere around 1967, this star-struck young man wrote to Mr. Karloff at his residence in London, sending an accompanying package of portraits, pleading with the immortal star to sign them. Some months later, a package arrived at my home, without an accompanying note. My praise and adulation had been absorbed, yet not addressed. Nonetheless, the hand of this great and gentle soul had dutifully signed each adoring photograph.

His health had been rapidly declining and by the early part of 1969 he had developed pneumonia. As the world prayed for his recovery, Boris Karloff passed from this Earth on February 2nd, 1969. A memorial service was held in his honor at St. Paul’s Covent Garden, known simply as the Actors’ Church. A commemorative plaque was placed inside the church, containing a quotation from Andrew Marvell’s Horatian ode “Upon Cromwell’s Return From Ireland.” It reads:

He Nothing Common Did or Mean

Upon That Memorable Scene

We shall not see his like again.