By Steve Vertlieb: While science fiction in cinema has always enjoyed enormous popularity around the world, dating back to George Melies 1902 experimental short A Trip To The Moon, few would argue that the cultural renaissance of the well worn genre occurred during its most prolific flowering from 1950 until 1959. Arguably, British cinema and television seemed to understand and respect the outer limits of imagination far more than their American counterparts, treating science fiction themes with more respectability and adult interpretation than expectation would normally demand. Alexander Korda’s London Film Productions glorified the subject matter in the Thirties with H.G. Wells Things To Come in 1936. With uncommon reverence for its massive presentation, Korda assigned distinguished classical composer Arthur Bliss to compose the music for the prestigious presentation.

That same serious consideration for the genre would be repeated during the science fiction craze of the Fifties, during which Britain’s tiny Hammer Films would rise to the stars as England’s chief exporter of domestic product. During its reign, Hammer Films would produce many of the finest science fiction and horror films of the period. From 1955 until 1976, the studio would film Shakespearean calibre excursions into the cinematic realm of the fantastic, featuring many of the most eloquent English-speaking actors and actresses of their day. The incomparable Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee would find their greatest success in Hammer Film series playing Doctor’s Frankenstein, and Van Helsing, Dracula and Frankenstein’s monster respectively. The exquisite Veronica Carlson lent her poetic presence to these dramatic endeavors, as well, finding rich delicacy in her subtle performances, as well as a rare sensual grace. It was with the same degree of respect and commitment that the studio would choose its musical tapestry, along with the composers who would create the unforgettable Hammer sound.

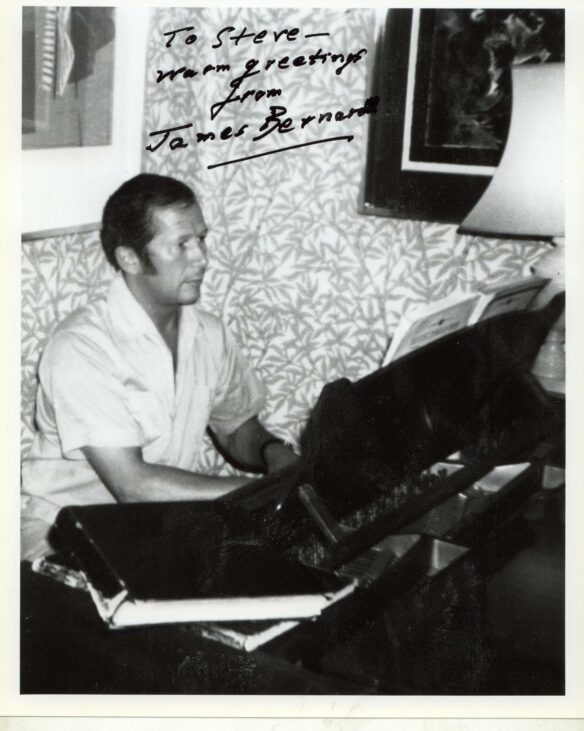

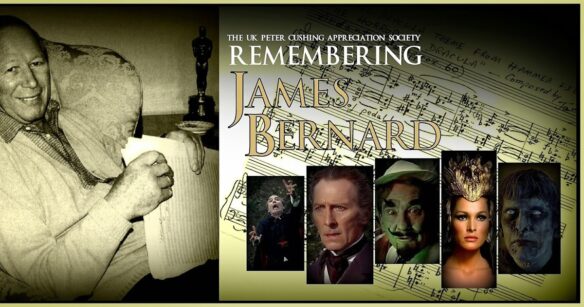

If any composer has been largely responsible for creating the sound of Hammer, or identified nearly exclusively with the musical significance and atmosphere for horror/fantasy films, it would almost certainly be James Bernard. Born September 20, 1925 in India, the son of a British Army officer, Bernard suffered from early ill-health and was relocated by his family back to his native England. Regaining his strength, he studied piano at Wellington College and joined The Royal Air Force where he served proudly until 1946. Interested in music at an early age, he began a correspondence with composer Benjamin Britten who suggested that he study composition at The Royal College of Music. Bernard had become something of a musical prodigy as a boy, offering piano recitals with ever-maturing skill and natural assuredness. While learning his craft under the tutelage of Imogen Holst, the young Bernard remained close to Britten, staying at the home of his mentor in 1950 when the older composer asked his student to copy out the vocal score for his opera Billy Budd.

A year earlier Bernard had met writer Paul Dehn with whom he formed both a professional and personal relationship lasting twenty-seven years. Together they wrote the original treatment for Seven Days To Noon, winning the Oscar for Best Writing, Motion Picture Story in 1952. The idea for the story had been formulated during a conversation between the two men in 1950 during which they wondered aloud what might become of the world they knew if nuclear madness were allowed to proliferate without rules of society in place to prevent such unbridled insanity. While the treatment would serve as a successful introduction to motion pictures, it wouldn’t be the last time film goers would either hear of, or listen to James Bernard.

BBC Television had produced a series of live science fiction serials in the early years of the decade focusing on the fascinating exploits of rocket scientist Bernard Quatermass who, engaged voraciously in the exploration of space, would ultimately need to defend his own planet from the onslaught of unwelcome predators from surrounding worlds. Written by the brilliant visionary author Nigel Kneale, The Quatermass Experiment was a huge success throughout the British Isles. Hammer Films was able to secure theatrical rights to the groundbreaking teleplays and assigned director Val Guest to helm the first of three films. The Quatermass Experiment was released in England under its original title and found recognition in The United States as The Creeping Unknown. Released theatrically in 1955 and featuring American actor Brian Donlevy in the lead as Quatermass, the first of the hugely popular science fiction melodramas had a bold, semi-documentary style approach in its presentation, lending a chilling, realistic focus to its other worldly tale.

Producer Anthony Hinds had originally contracted composer John Hotchkis to write the music for the film but, as fate so often determines, Hotchkis grew ill and was unable to fullfill his assignment. Hinds telephoned John Hollingworth, conductor and eventual Music Supervisor at Hammer, to ask if he might suggest another composer to fill the vacancy left by the ailing Hotchkis. Hollingworth suggested a young, twenty-nine-year-old composer who had recently written a successful score for a BBC radio play of The Duchess of Malfi. His name was James Bernard. Hollingsworth, according to writer David Huckvale in his biography of Bernard (James Bernard: Composer To Count Dracula, McFarland, 2006) notes that Hollingsworth was reluctant to offer the young composer a larger orchestra to perform his first film score, and so the twenty or so minutes of music for the film were performed entirely with a string ensemble and played, under Hollingworth’s direction, by The Royal Opera House Orchestra. The three-note theme written by Bernard for The Quatermass Experiment was a stark, bone chilling instrumentation predating Bernard Herrmann’s searing string score for Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho by five years. Bernard’s visceral music for the picture perfectly captured the grim mood of the horrific tale realizing, in its striking notes and themes, the bleak predominant threat of an alien infestation destroying London.

The studio wanted to do a follow up to the initial “Quatermass” story, but Nigel Kneale refused at first to allow his character to be used by Hammer again, due his personal distaste for American-born actor Brian Donlevy. Losing neither sleep or disquiet over Kneale’s refusal, Hammer assigned writer Jimmy Sangster to write an original Quatermass screenplay without using the name of Kneale’s protagonist. In 1956 Hammer released X-The Unknown, directed by Leslie Norman, and featuring American actor Dean Jagger as the embattled scientist fighting both alien invasion and the British political establishment. Composer James Bernard would once again contribute the very effective score and, to all appearances, this next Hammer shocker was in every way, save for both character name and permission, a “Quatermass” film.

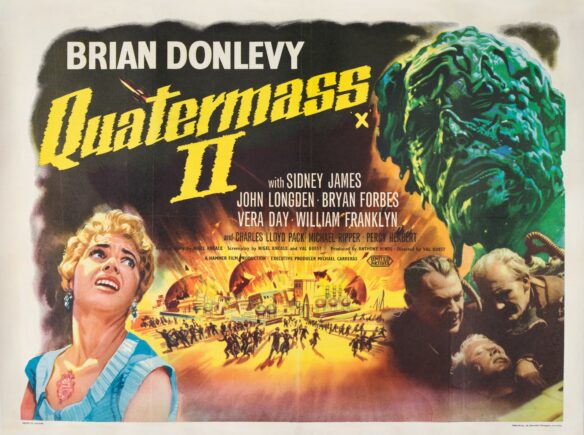

Hammer followed their instincts and produced the second installment of the original Nigel Kneale trilogy a year later when Quatermass 2 was released in 1957 throughout England. Enemy From Space was the American title for the Val Guest-directed shocker, once again starring Brian Donlevy as Professor Quatermass with another chilling science fiction score by James Bernard. Apparently, Nigel Kneale had relented in his initial displeasure, now allowing the studio to adapt his second teleplay for filming. Following the same semi-documentary approach as he had used in the first film, Guest guided his actors in frighteningly realistic style to a spectacular conclusion in which huge gelatinous creatures, resembling H.P. Lovecraft’s “old ones,” collapsed in excruciating torment to the striking accompaniment of James Bernard’s economic, yet unforgettable themes.

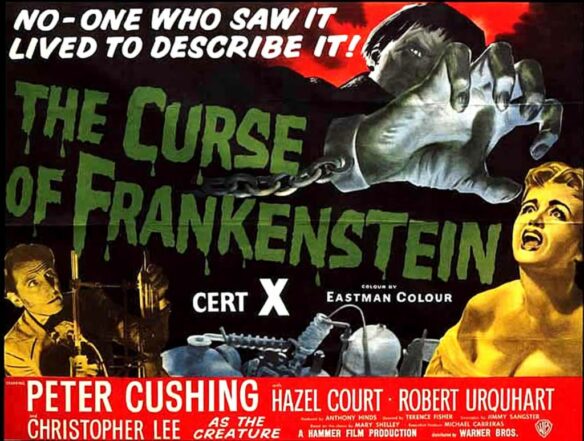

James Bernard was now solidly a member of the Hammer repertory company. What has now become known as the Bernard years, however, would officially begin the next year in 1957 with the release of the first of Hammer’s legendary recreations of the classic Universal monster series. Curse of Frankenstein was essentially a modern retelling of Universal’s 1931 production of Frankenstein starring Boris Karloff as The Monster, and Colin Clive as his creator, Henry Frankenstein. The startling new production would feature Hammer’s lurid color trademark, accompanied by sexual situations, and graphic violence. Starring Peter Cushing in his first outing as Doctor Victor Frankenstein, and Christopher Lee as his abominable experiment gone horribly wrong, Curse of Frankenstein ignited world box office records as the innocence of the original Universal productions was replaced by explicit thrills for a new generation of monster enthusiasts jaded, perhaps, by the simplicity of the earlier films. James Bernard composed the score for the film which was as profoundly impactful and dramatic as the characters and colorful horror for which it was driven.

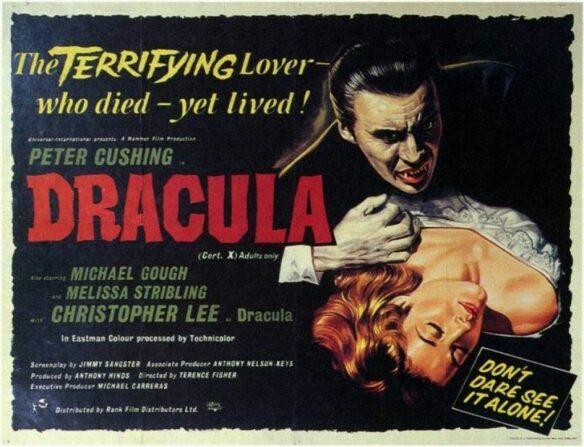

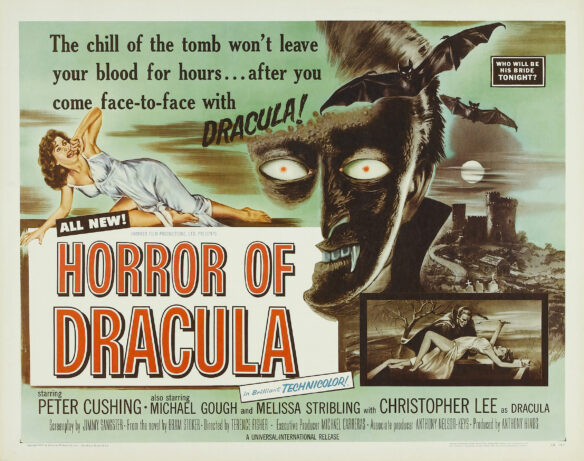

1958 would provide the composer with, perhaps, his signature work. Now that Hammer had successfully begun mining the riches of Universal with Curse of Frankenstein, the obvious choice for their next classic monster revival was The Monster’s caped counterpart, Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Peter Cushing was signed once again to play off his earlier rival, Christopher Lee. This time Peter Cushing would play Dr. Van Helsing, while the tall, aristocratic Lee would essay the vampiric count. Released once again in lurid British Technicolour, with graphic bloodletting and even more provocative sexual situations, Dracula would prove Hammer’s greatest triumph. Released in America as Horror of Dracula, this first vampiric foray by Hammer remains among the most notable, striking visualizations of Bram Stoker’s acclaimed novel. For Dracula, Bernard would compose his most demonstratively mature, symphonic music for films to date. The three-note salutation has become internationally recognized as Dracula’s theme, while the rest of his full-bodied score is as remarkable and memorable as the film itself. Directed by legendary film maker Terence Fisher, with star making performances by both Cushing and Lee, and a thrilling score by a composer beginning to feel more confident of his gift, Dracula became the standard by which all successive Hammer Film Productions would be measured.

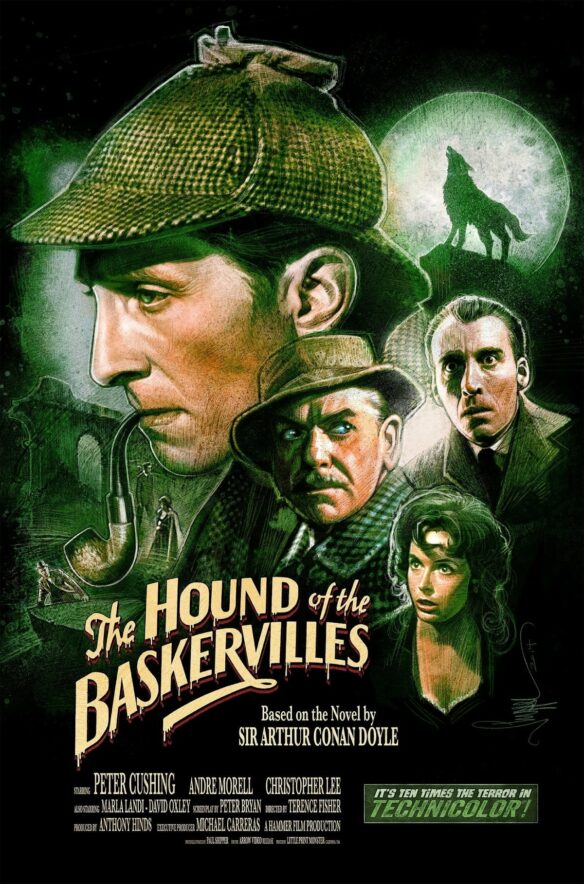

Hammer’s next distinguished pairing of actors Cushing and Lee, with composer James Bernard, would be yet another retelling of both a classic novel and motion picture. However, this time the studio would turn to mystery, rather than horror, with a new version of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s definitive detective yarn, The Hound of the Baskervilles. Filmed earlier by Twentieth Century Fox studios in 1939, the original film would feature the legendary pairing of Basil Rathbone and Nigel Bruce as Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson in their initial appearance as the iconic sleuths, along with Richard Greene as Sir Henry Baskerville. For the full-color version from Hammer, Peter Cushing would play Sherlock Holmes, while Christopher Lee would essay the part of Sir Henry Baskverville. Andre Morell would appear as Dr. Watson. Directed once more by Terence Fisher, this gothic dramatization remains, perhaps, the definitive interpretation of the Conan Doyle novel. Cushing, born to play the fictional detective, delivered one of his most distinguished and energetic performances. It is difficult to imagine a more perfect Holmes than Peter Cushing, with Basil Rathbone alone sharing contention for the screen’s most memorable Holmes interpretation. Hammer, however, couldn’t quite resist the temptation to turn the Doyle classic into a horror film. Since the story is traditionally hovering on the border between suspense and terror, Hammer’s graphic treatment was hardly out of line. James Bernard’s distinctive music for the picture is brooding, commanding, and eerily effective, creating a sense of encroaching danger upon the dreaded moors.

The Kiss of the Vampire, released by Hammer in 1963, was a thoughtful tale of vampiric infestation in a rural Balkan village, and featured a lovely suite by James Bernard who, by now, was truly maturing as a superior screen composer, as evidenced by the superb piano concerto written by Bernard expressly for this often-forgotten gem from Hammer.

Bernard’s next assignment from Hammer would rank with his finest, most haunting contributions to the genre. The Gorgon, released by Hammer Films in 1964, and starring Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee, along with Barbara Shelley and Patrick Troughton, featured a beautiful, mesmerizing score by Bernard, capturing the hypnotic menace and legend of the awful mythological creature who could turn men to stone with a mere glance of her hideous features.

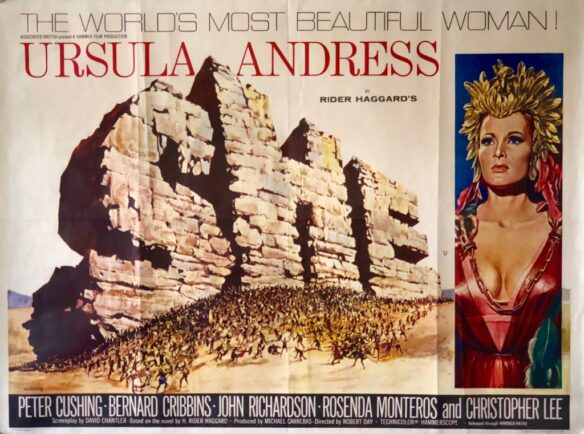

Hammer turned to one of their most ambitious productions in 1965, choosing to re-imagine H. Rider Haggard’s epic novel She once more for the screen. Filmed earlier at RKO by Merian C. Cooper in 1935 with Randolph Scott, Nigel Bruce, and Helen Gahagan Douglas, an expensive new production in full color would star Peter Cushing, Christopher Lee, and Ursula Andress as the ageless queen. While cinematically daring, at least on paper, the completed production of She was, in the end, strangely static in its execution, with performances that appeared unaccountably bored, stiff, and disinterested. The one area, however, in which the film did succeed beyond its most earnest ambitions was in the musical scoring by James Bernard. Rich beyond words, and lush beyond reason, Bernard’s magnificent score for this often turgid film brought to mind and heart all of the stunning legend of an ancient sorceress who might live eternally, providing the haunting and unforgettable musical imagery sadly lacking in every other aspect of the compellingly mediocre visualization.

In the years that followed, Hammer would remake many of its earlier hits with both Peter Cushing and Christopher Lee reprising their earlier triumphs, hoping to find cinematic treasure once again. The results were sporadic, offering rare moments of gold interspersed with uninspired tedium. While scripts may have become increasingly tired and mundane, however, the performances by Cushing, Lee, and James Bernard rarely lost their magical spell over audiences. While more closely identified with the bombastic themes for Dracula and Frankenstein, James Bernard revealed a softer, more poetic side to his musical signature as the familiar series wore on, writing some of the most lovely, unabashedly romantic music of the period. He would often insist that these gentler themes would identify his music far beyond the recorded recollection of those written for horrific thematic identification, and that these rhapsodic interludes would more clearly define his musical legacy. Indeed, desperation on the part of corporate executives to somehow recapture a fragment of the magic of their earlier efforts, may actually have filled a creative void in the heart of the composer, much as it had with his music for She. While each successive sequel demanded yet another failed homage to the films that had initially inspired them, James Bernard was asked to recall thematically the torrential music that launched a thousand ships. He found artistic solace, however, in the deeply sensitive and introspective music created for the quieter intervals in each of the studio’s sequels.

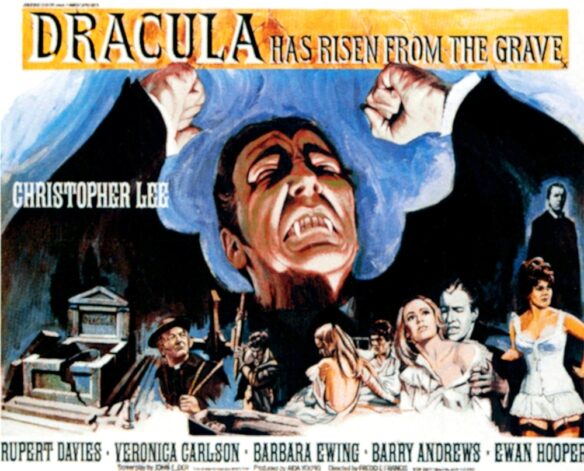

Bernard remained actively working for a variety of British filmmakers in the years that followed, writing the music for Dracula, Prince of Darkness (1966), The Plague of the Zombies (1966), Torture Garden (1967), The Devil Rides Out (1968), Dracula Has Risen from the Grave (1968), Frankenstein Must Be Destroyed (1969), Frankenstein and the Monster from Hell (1974), and the ill-fated The Legend of the 7 Golden Vampires (1974). While The Devil Rides Out was a somewhat tepid screen translation of the famed novel by Dennis Wheatley, its score remained the composer’s personal favorite of his own works, illustrating once more David Raksin’s contention that “good music has saved more bad films” than one could ever realistically imagine or expect.

There were some gems, nonetheless, interspersed along the way featuring sparkling musical champagne from the skilled hand of a now seasoned, gifted, and versatile composer. One has only to listen to the deeply sensitive, profoundly exquisite, romantic melodies delicately elevating the quieter interludes in such films as Frankenstein Created Woman (1967), Taste the Blood of Dracula (1970), and Scars of Dracula (1970) to recognize, and properly evaluate the poetic genius and stature of this gentle soul. Indeed, Bernard felt most comfortable with these tender, affectionate themes, sensing somehow that his true value as a composer might one day come to be recognized more for his unabashedly romantic interludes than for the full orchestral assaults associated with the more horrific aspects of his Hammer film scores.

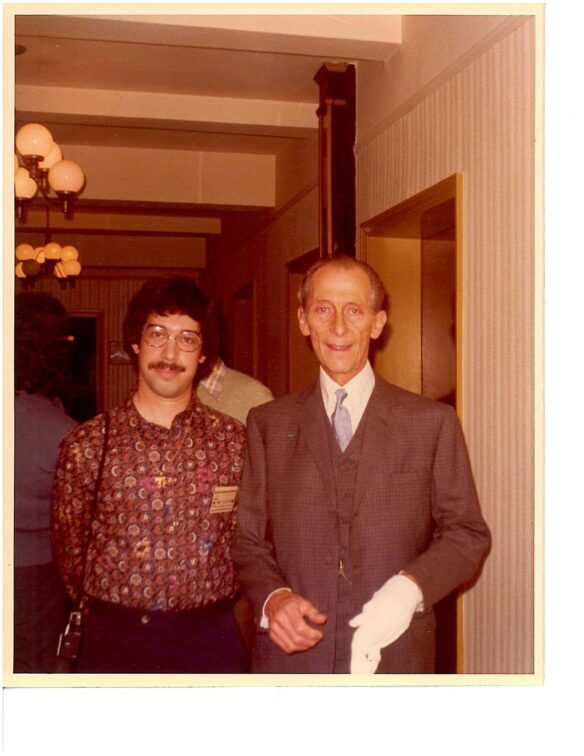

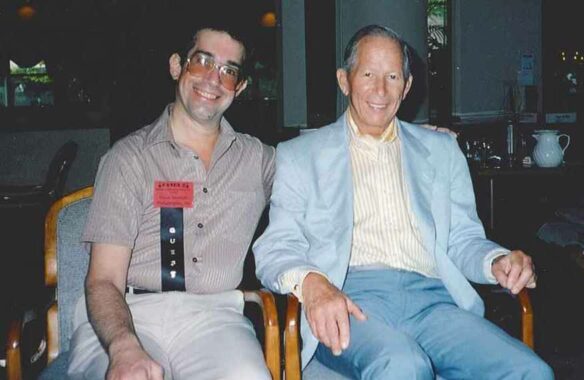

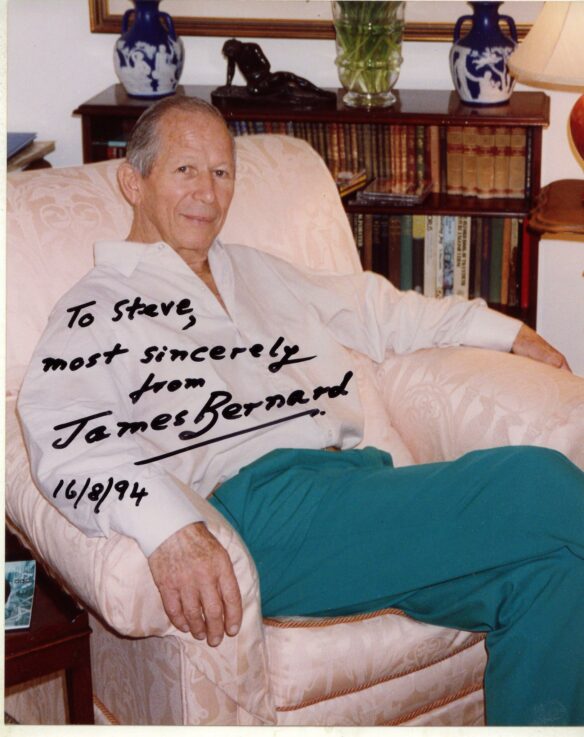

Tragedy befell James Bernard in 1976 when his trusted friend and life partner Paul Dehn was killed in a tragic act of violence. Traumatized by this senseless loss, Bernard retreated into both emotional and artistic retirement for many years. It was somewhere about 1997 when James Bernard’s creative energy and juices returned him to the medium he was born to write for…motion pictures. Still relatively young, Bernard yearned to return actively to composing for films. I met the composer in 1994 at a Fanex film conference in Baltimore sponsored by Midnight Marquee Magazine, and we became fast friends. He was simply “Jimmy” to those he regarded as chums, and I was happily to be counted among this rapidly growing circle of companions. Jimmy would often telephone me from his home in London on Sunday mornings, and we maintained an active correspondence over the years remaining to him. He had gotten himself an agent in London, actively seeking film and television work once more. Assignments were slow in coming, however, to a musician whose age surpassed seventy years, and whose musical presence had been missing for so many years. One Sunday morning, by telephone, he asked me if I thought that hiring an American agent in Los Angeles might lead to greener pastures in Hollywood. I wrote to Elmer Bernstein, whom I’d known for many years through correspondence, asking his thoughts on the matter. Despite his own advancing age, Bernstein was still working rather productively in the industry. Bernstein wrote back, entirely in sympathy with Jimmy’s desires to remain active and productive. The reality, however, was that Bernstein…by his own description…was “a dinosaur,” and that film producers were looking for “kids,” rather than older men. He remarked that he was uncommonly fortunate to still be working at his craft.

Even if new assignments weren’t immediately forthcoming, however, there seemed to be renewed interest in his earlier work. Silva Screen Records in England offered Jimmy an opportunity to prepare new concert suites for some of his scores with the intention of recording them for commercial release. Jimmy was anxious to get back to work, but had some reservations about the accessibility of his music for the Quatermass films. During the course of a letter, and later a telephone conversation, he asked if I thought that the earlier scores would either translate into listenable recordings, or if there would be any serious interest by fans in having a suite for Quatermass recorded for CD release. I assured him that there would be enormous interest in having his music preserved by Silva, and that he needn’t spend any more needless time worrying about the success of such a recording. Happily, his music for the Quatermass series was recorded in 1996, along with his carefully prepared and selected suites from She, Kiss of the Vampire, Frankenstein Created Woman, The Devil Rides Out and Scars of Dracula. Conducted by Kenneth Alwyn, Nic Raine and Paul Bateman, The Devil Rides Out: Music For Hammer Films…The Music Of James Bernard (FilmCD 174) is a marvelous celebration of Jimmy’s remarkable music, both splendidly conducted and performed by The Westminster Philharmonic Orchestra, together with The City Of Prague Philharmonic Orchestra.

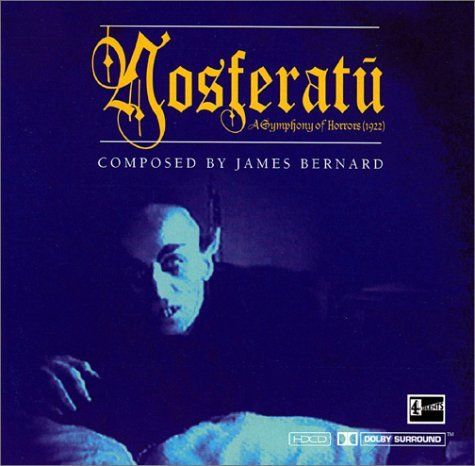

Fortune would intercede a year later when an enterprising producer asked Jimmy to score a newly remastered edition of F.W. Murnau’s silent horror masterpiece Nosferatu for a new generation of film enthusiasts. Plans were in the works to release the film theatrically, with a DVD of the restoration to follow. Jimmy was elated at the prospect of returning to his roots. Happily at home once more, the resultant score by James Bernard for the German expressionistic classic would become among the finest works of his career. Nosferatu is a masterful work, a wonderful symphonic coda to a distinguished screen career.

The score was premiered at a prestigious, live concert event at Queen Elizabeth Hall in London on November 17, 1997, in which the iconic motion picture was unspooled before an enthusiastic capacity audience, accompanied by a large symphony orchestra. Among the invited celebrity guests that evening was the score’s composer, James Bernard. Ironically, plans for a theatrical release were abruptly canceled when funds were not forthcoming and, as often occurs in theatricality, this was ultimately a promise that was not to be. Frustration by Jimmy was tempered by an offer by Britain’s Silva Screen Records to record the seemingly lost score for posterity on CD. I cried through much of my first listen to the commercially released recording, for this was not the work of an old man but, rather, the passionate symphonic rebirth of an artist who had simply been away for a time, while growing immeasurably as a musician. There were echoes of Hammer’s Dracula films, to be sure…but, more importantly, the new work represented a fresh, vital, and important reinvention of a singular composer’s miraculous gift for musical expression. Exhilarated and profoundly moved by the experience, I sat down to write Jimmy a letter of my joy and exultation over his achievement, expressing my sincere belief that his score was easily the finest new film music of the year. Not long after receipt of my letter, there was a telephone call from him in which he thanked me profusely for my critical analysis of his work. It was a moment of friendship, bonding, and genuine affection between us that I don’t think I’ll ever forget.

The following year saw Jimmy writing the music for a wonderful new television documentary, produced for Turner Classic Movies, documenting the history and tradition of early horror films produced by Universal Studios. Universal Horror provided a sublime look into the past of the legendary studio that had offered the inspiration for Hammer Films’ remarkable rise to international recognition and success. It seemed fitting, then, that James Bernard compose the decidedly atmospheric music lovingly caressing the haunting documentary.

In the years that followed, Jimmy’s health was sadly deteriorating, while film work seemed to diminish substantially. On July 12, 2001, James Bernard quietly succumbed to years of disturbingly debilitating illnesses. Jimmy is gone, but the light, laughter, and brilliance that illuminated his soul remains ablaze in the flickering image upon the screen, and on the wondrous soundtrack of our collective memories and experience.

++ Steve Vertlieb — Halloween, 2011

Steve Vertlieb Remembers James Bernard – The Musical Heart & Soul Of Hammer Films: “In June 2014, cinema archivist / historian / educator Steve Vertlieb took time before our documentary cameras to reminisce on his special friendship with legendary film composer – the late great James Bernard, best known to many as the primary musical voice of the classic 1960’s era horror and sci fi films of England’s Hammer Studios…”