Dark Corners and Illumination

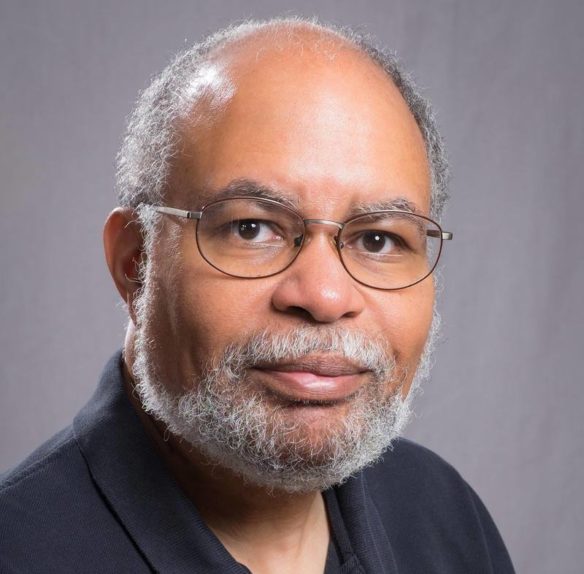

By Chris M. Barkley:

“Let me reiterate: Racism is a system. As such, it is fueled as much by chance as by hostile intentions and equally the best intentions as well. It is whatever systematically acclimates people, of all colors, to become comfortable with the isolation and segregation of the races, on a visual, social, or economic level—which in turn supports and is supported by socio-economic discrimination.”

From The New York Review of Science Fiction: “Racism and Science Fiction” by Samuel R. Delany, August 1998. (https://www.nyrsf.com/racism-and-science-fiction-.html)

Professor Henry Jones: Elsa never really believed in the grail. She thought she’d found a prize.

Indiana Jones: And what did you find, Dad?

Professor Henry Jones: Me? Illumination.

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, written by Jeffery David Boam, 1989.

When I was growing up, children like myself were taught, no, more like indoctrinated, to think the United States was the BEST place to grow up, that our country was ALWAYS in the right and that our institutions were, for the most part, unassailable and impervious to criticism from anyone, especially foreigners.

I grew up in Ohio in the 1960’s and despite what I was being taught in a parochial Catholic grade school (at great expense, I might add, by my hard-working parents), certain things I was experiencing did not add up. News of the violence and casualties during the Vietnam War was inescapable. I remember watching the evening network news broadcasts and being horrified by the number of people (on all sides of the conflict) being wounded or killed on a daily basis.

As the years went on, it became harder to reconcile all of the violence, terrorism, public assassinations and the racism I was experiencing with the education I was receiving. The Pentagon Papers and the Watergate break-ins coincided with my high school years and the beginnings of my political awakening.

When I look back on those formative days of my life, I see myself as a small child, set out upon a sea of prejudice and whiteness, in a boat of hetero-normaltity, destination unknown.

You should also keep in mind in this era of American history, the civil rights movement was supplementing the struggle for basic human rights alongside a growing emphasis on the pride of being Black and uncovering the suppressed history of women, other various minorities and oppressed peoples.

Needless to say, there was very little representation of minorities (of ANY kind) on television and the movies then, but when there was, our household paid attention. Bill Cosby as an undercover intelligence agent on I Spy. Diahanne Carroll was a compassionate nurse, Julia. Genius engineer Greg Morris on Mission: Impossible. Gail Fisher as Joe Mannix’s hip assistant. Eartha Kitt as Catwoman on Batman. Nichelle Nichols on Star Trek. And Sidney Poitier in, well, anything.

With that small awakening within me, came the realization that the institutions that I was taught to revere without question had glaring flaws, if not dark corners. Outright villany in their ranks. The United States military and industrial complex. Politicians on both sides of the aisle. Walt Disney. Harvard University. Police departments, everywhere. Kelloggs and General Mills. Major League Baseball and National Football League. Oil and gas companies. Automobile manufacturers.

And, as I gradually found out, in sf fandom’s past as well. (More on this later in the column.)

It was with this mindset that I formally entered sf fandom in June of 1976. It was as though my metaphorical had landed on an undiscovered land of opportunity and discovery.

Bright eyed, bushy tailed and somewhat politically aware, I plunged right into Midwestcon 27 with gusto. Besides the friend I came with, Michaele, we knew no one there. Fortunately, the Cincinnati Fantasy Group welcomed us both with open arms.

I will note that although almost all of the members of the CFG at that time were white, there was one other member at that time who was probably the first person of color to join the group, the late Frank Johnson.

Frank, who passed away in March of 2019 at the age of 65, was a good friend over the years, had first attended Midwestcon in 1968 along with a good friend of his, Joel Zakem, who both became full fledged members of the CFG a year later. I knew him and I was grateful to know him as well.

Then, and now, the members of the CFG have treated me with respect. I have truly felt that from the beginning, they have treated me as their peer and an equal. Any animosity or disagreements I may have had with any of them, I felt as though racial animus was never a factor in those matters.

In fact, during the first two decades that I attended literary sf conventions, I felt as though I was completely safe. In addition, I also thought I was positively egalitarian among my peers and I believe they felt the same way about me. Any problems I had at conventions in that era, which I have chronicled here in the past, were from people outside fandom who openly questioned or doubted I should be in such spaces. But I may have been wrong.

During those early days in fandom, I was either an attendee, a panelist or in the lower chain of command of volunteering at conventions.

As I rose through the ranks of conrunning, I was still seen and sought after for assignments and advice. However, as I became more politically engaged through my twenty years of activism at the WSFS Business Meetings, I became gradually aware that some people were not entirely happy with the changes I was trying to implement through changing the Hugo Awards. One of the main reasons I was trying to push through those changes was because it was becoming readily apparent to me that there was a schism between younger fans who favored media based conventions and older fans who celebrated films but preferred author-driven conventions.

The seeds of this separation were sown from the growing ascension of Star Trek conventions in the mid-1970’s and the explosive (and surprising) success of Star Wars, whose debut irreparably blew the doors off both fandom and the media landscape as well.

The catalyst for this column began with the pointed meme by Andrew Trembley (at the top of the column) on April 18 and this post on the JOF Facebook page on the very same day:

“Question for the group. Why do we as a group (science fiction conventions) do such a poor job of getting BIPOC? From what I can see we get less than 5%. But you go to a comicon and there are hundreds, go to a SF convention maybe 10 or 20?”

THIS is not a new problem for fandom. POC and other marginalized groups have been asked this question over and over for several decades now, and usually by well meaning white or privileged fans, who demand BIPOC fans come up with the answers to a problem they systematically keep perpetuating.

I subsequently read EVERY single response to the query and at some points, it got very ugly. There are some people in fandom who are still under the false impression that fans outside of their sphere are uninformed, ignorant or just plain undesirable to associate with. These sorts of comments weren’t new to me, I had encountered them more than twenty years ago through emails and early internet bulletin boards.

Then, on April 22, while doing research about addressing that very question, Kat Tanaka Okopnik re-posted this blog post on JOF from 2021 on two days earlier: “Jim Crow, Science Fiction, and WorldCon” by Bobby Derie at Deep Cuts in a Lovecraftian Vein.

Wherein I became reacquainted with some not so very flattering history of Cincinnati Fandom:

[Gene Deweese had] been corresponding with a girl, Bev Clark, in northern Indiana, and wanted me to go with him to meet her, which suited me fine; I was finally finding girls I could talk to. Gene arranged things and we went up. It was the first time I’d met a black (or African-American, if you prefer) person socially. We got along fine, and later on we’d arranged that the three of us would drive to Midwestcon, again in my car; that car got a lot of use that summer; Juanita and her friend Lee Tremper would meet us there, and we’d have fun. We arrived at Beatley’s Hotel (or Beastley’s-on-the-Bayou, which was one of the fannish descriptions at the time) but Bev was refused admittance. No blacks allowed. None of us had even considered the possibility. On the way out, we talked to a few fans sitting on the hotel porch and some anger was expressed, especially by Harlan Ellison, who said that all fandom would hear about this outrage. We drove home, and as far as I know, nobody ever mentioned the episode again. Except me, of course.

—Buck Coulson, “Midwest Memories” in Mimosa #13 [PDF] (1993), 36

That was in 1953; Coulson added that later that year Bev attended the 1953 WorldCon in Philadelphia with them and there were “no room problems.”

When my friend Michaele and I attended Midwestcon 27 twenty-three years after this infamous incident in June of 1976, we were both blissfully unaware that the convention had been embroiled in such discriminatory acts towards people of color in the 1950’s. Why would we? We had just stumbled on to one of the greatest continuing parties of our lives, that’s why. We had entered fandom at a time when the elder members of the Cincinnati Fantasy group were exiting or dying off and a new generation were just joining.

In light of all of this history, I must give pause to think and question what actually happened during my 46 years of fandom.

Was the opposition to my activism regarding the Hugo Awards treated as altruism (as I saw it on my part) OR, were people opposing me because of my “outsider-other” status, or was it more plainly, but hidden, racial prejudice against me? At the moment, I don’t know. And frankly, I am very comfortable with my actions and how I conducted myself while I was a fan activist between 1999 to 2019 to leave that judgment to historians and literary critics.

I should also say that out of this cauldron of frustration and angst came some actual illumination.

On April 19, Kris ‘Nchanter’ Snyder (pronouns they/them), a veteran con runner of many years and person of color, laid out a formative set of guidelines they have developed over the years on the JOF (Journeymen of Fandom) Facebook page. (Quoted with permission) To wit:

So you want more Fans of Color at your convention? I’ll repeat (some of) the advice we’ve been giving you. In order:

1) Listen to what non-white fans are telling you and stop arguing with us that it can’t be that bad. We’re not actually telling you everything. This means doing research by using Google to read blogs and things. Don’t engage, just read. If this is exhausting or makes you uncomfortable, I promise it’s 10x more so for those of us who live it.

2) Deplatform your bigots, and anyone who thinks bigots deserve a seat at your table. Anyone who refuses to put in work to root out bigotry, who complains about attending sensitivity training (unless they are a member of imperiled marginalized groups, but like, even then) is a PROBLEM and needs to not be on panels, and not be on staff.

3) Pay for sensitivity training for your staff. Yes, pay. You want someone good, and preference should go to trainers who are not-white. It’s just as important as making sure there is first aid training or people are serve-safe certified.

4) Make sure your code of conduct covers racial harassment, have a clear reporting and follow up process, have members of that team go through extra training, and then do all the hard follow up work. It’s 2022. Have an anti-racism statement that you make sure your staff is following and refers back to when setting goals.

5) Create safer spaces at your convention. This acknowledges that you know there are problems, and you are committed to doing work to address them.

6) Spend money on accessibility services. (You should have been doing this already, but I’m adding it in here. And god help anyone who asks why this is in here when we’re talking about racial inclusion).

7) Set up and spend money on an inclusion fund to help people who need financial assistance get to the convention. If you have this, and advertise that it takes donations, people will donate to it, and fans of color who don’t need the services are more likely to come to your convention because it is a sign that you care.

8.) Commit to doing this for 5 years before you come back and whine that it’s not working.

And though you’d think that post would have been a definitive endpoint to the discussion, people rambled on. As the weeks progressed, it seemed as though there would be no end to this roundabout discussion among the participants.

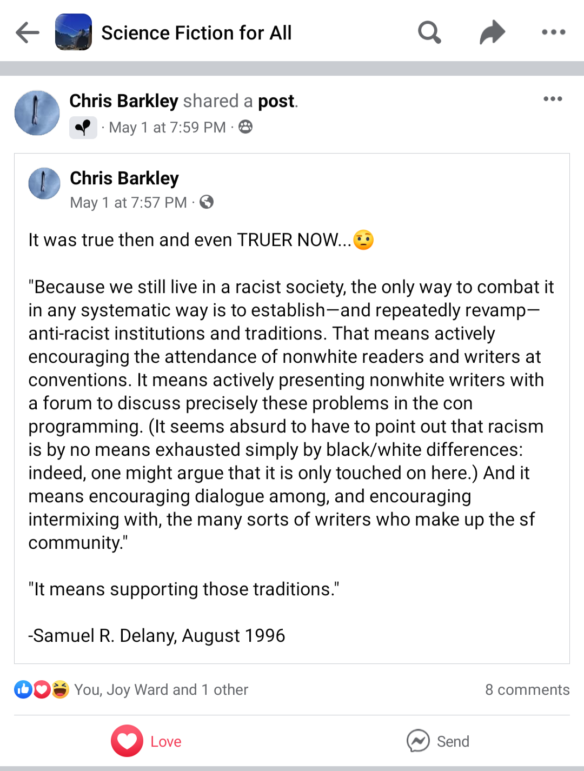

To accentuate my position, I took it upon myself to post another excerpt from Samuel Delany’s racism essay across Facebook, including a group I am an active member of, Science Fiction For All. Unfortunately, I inadvertently posted the quote twice. The first post was received very favorably by the few members who bothered to comment. The duplicate however, attracted some very unwanted attention…

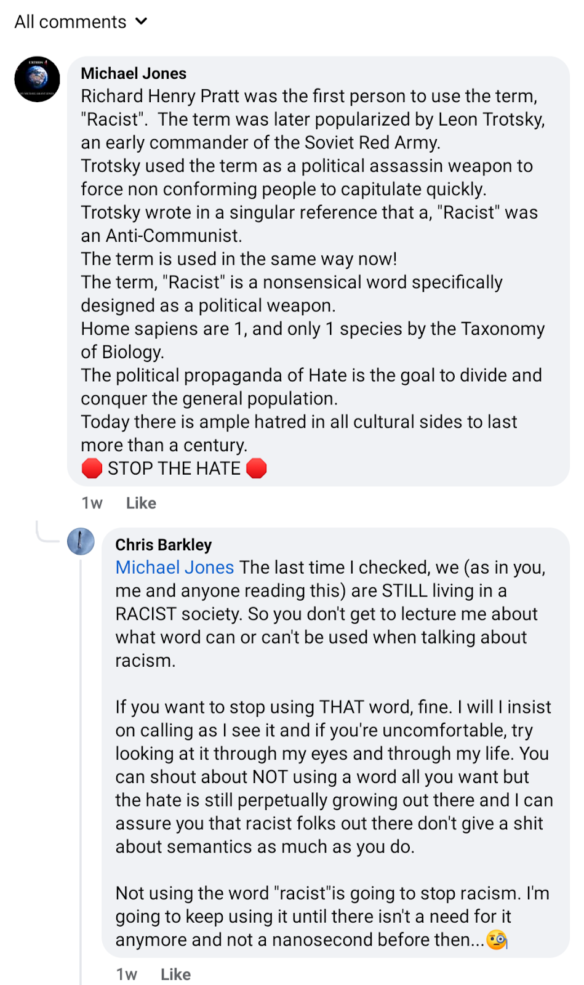

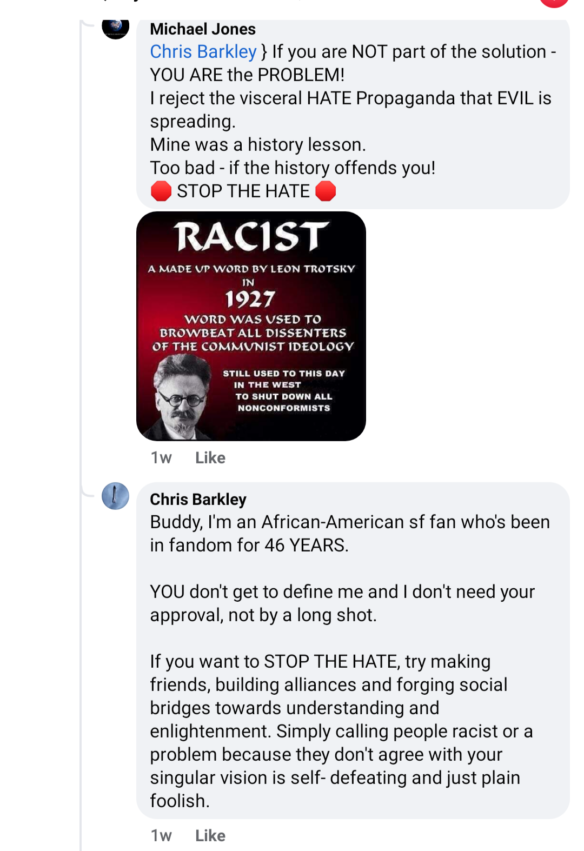

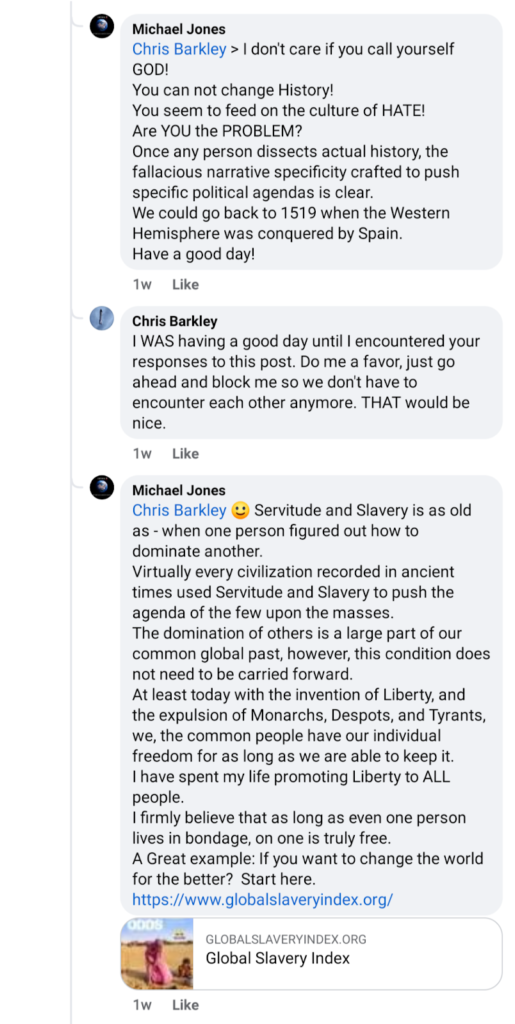

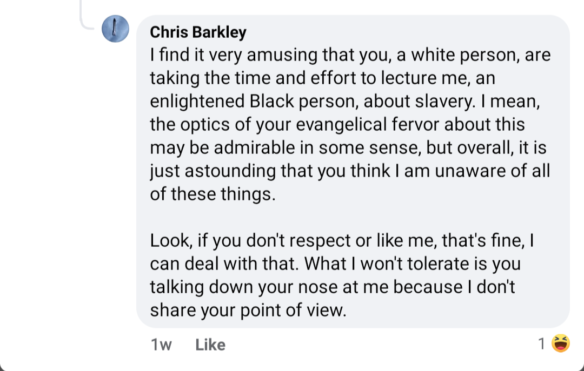

I wasn’t expecting any comments at all. And if I had known there was a duplicate post at the time, I would have readily deleted it. Instead, I was “gifted” with the presence of one Michael Jones, who proceeded to tell me, in great detail, that my post was extremely problematic:

As some of you may have suspected, the laughing emoji was supplied by Mr. Jones as a parting shot. Sometime between our encounter online, he left as a member of the Science Fiction For All Facebook page. (Whether he was pushed by the admins or jumped on his own is unknown.) I think I can safely say that he will definitely not be missed by me (or a great many of the current members).

I speculate freely that Mr. Jones is a part of the fannish community that was brought by his parents (and peers) to believe that people matter MORE than their racial ethnicity or national origin. Which is fine, except that as history has shown that setting aside those factors misses the point that continually ignoring people’s cultures, colonization, subjugation and oppression, really DO matter.

In the end, we all must realize that in addition to our personal experiences, we also bring our own sets of biases and prejudices as well. The first step in dealing with some of the more pressing issues in the various factions of fandom today is coming to the realization that these problems exist and that we should be very aware of our own personal shortcomings, or at least be willing to listen and accept constructive criticism when we are confronted with them.

I, and many others have called science fiction (and by inference, fantasy as well) the literature of change. And by change I mean shifts in perspective, either by historical, societal or technological means.

There have been times when I have marveled with dismay that the people who love and admire this branch of literature, can also be the most obstinate, stubborn and hidebound when it is plainly evident that a change in thinking or policy would be a great benefit to fandom.

On the whole, these changes, whether it is for either individuals or our society, is hard but inevitable.

How fandom ultimately deals with it will define us all, for better or for worse.

Let’s emerge from the dark corners. Let’s choose illumination.

There is no ‘them’ and ‘us.’ There is only us.

– Greg Boyle

This column is dedicated to the memory of Frank Johnson, sff fan, global traveler. collector, and a masterful lover of music, art and life itself. (Friends Pay Tribute To WGUC Announcer Frank Johnson | WVXU)