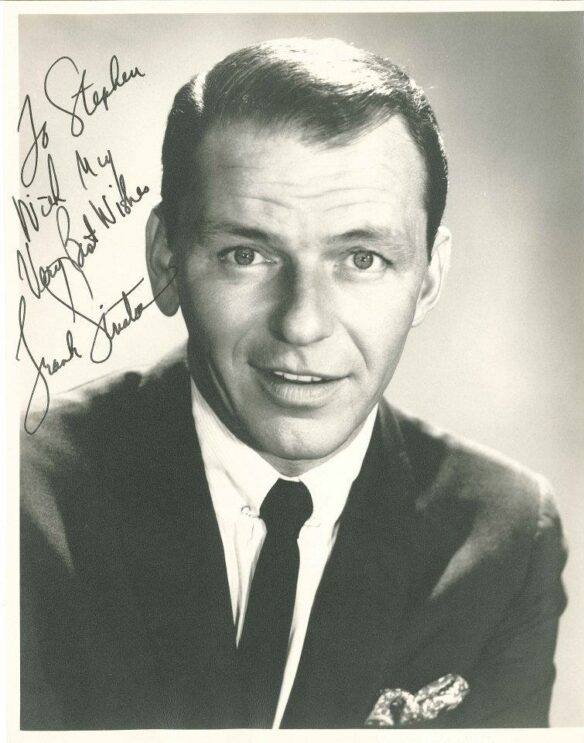

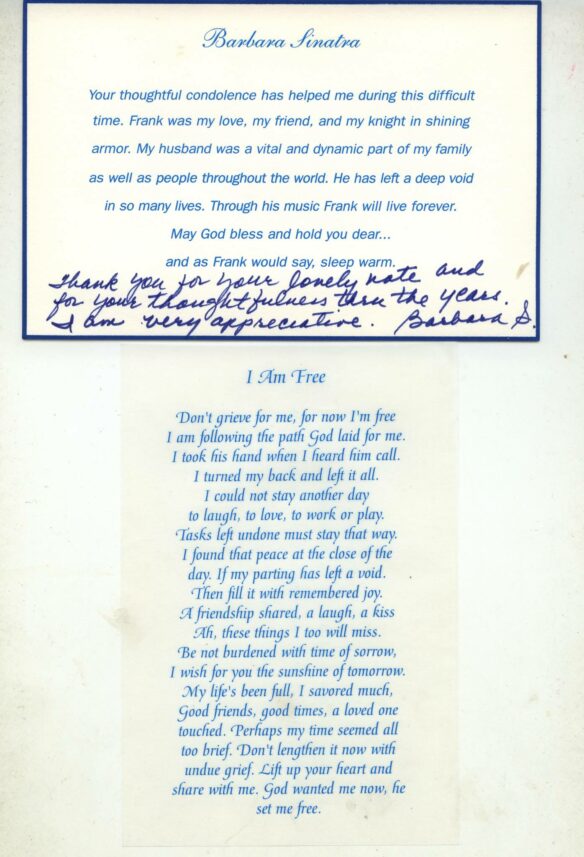

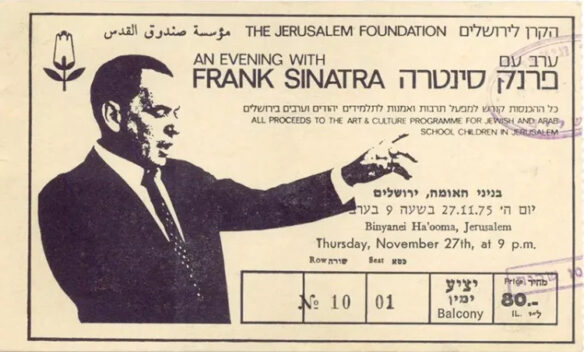

By Steve Vertlieb: This is a love story, as wondrous, tender, and affectionate as any that you’ll ever read. In the current vernacular, it might be referred to as a “bromance,” the non-romantic affection for one man by another. For, in all my life, I have never felt the adoration for another human soul…beyond my brother, my parents, and my beloved girlfriend, Shelly, that I have felt for more than half a century for a man called Sinatra.

Music and films have, I imagine, played an integral role in my life from my earliest memories, perhaps as early as 1950 when I was but four years old. We got our first television set that year and, from the moment that the magical square box came to life, I would be permanently and adoringly enchanted and entranced by the sights and sounds that came lovingly from its intimate screen and speakers.

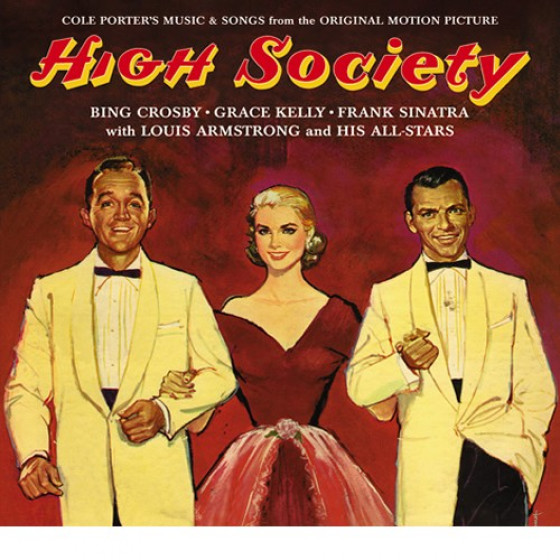

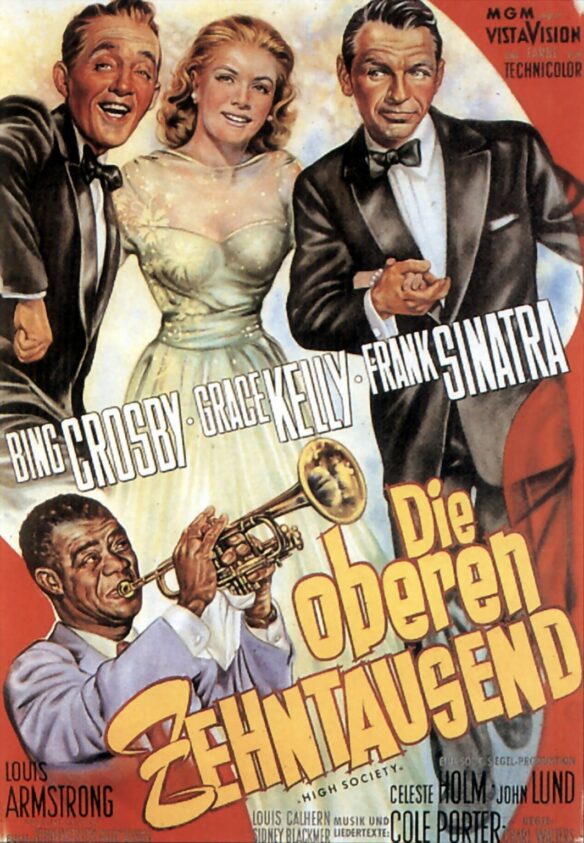

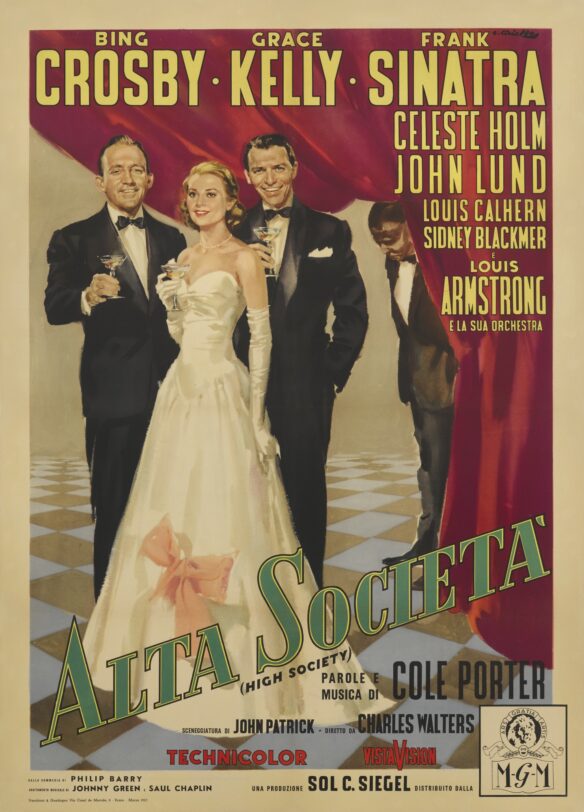

In my early youth, my mom and dad would take me to the movies, either at our premiere local movie house, The Benner Theater or, during more sophisticated journeys beyond the realm of the Oxford Circle in Northeast Philadelphia, to Philadelphia’s first-run downtown theaters such as The Mastbaum, The Stanley, The Boyd, The Fox, The Randolph, The Stanton, or The Arcadia. My dad would always take me to see adventure movies such as Ivanhoe with Robert Taylor, The Searchers with John Wayne, or Mogambo with Clark Gable. My mom, on the other hand, would escort me to the big musicals of the time such as Annie Get Your Gun with Betty Hutton and Howard Keel, The Bandwagon, with Fred Astaire, and a little musical opus from the pen of Cole Porter called High Society. It was during a screening of the latter motion picture that I first encountered Frank Sinatra on the big screen in 1956.

Now, to be candid, my singular man crush of the period was with Bing Crosby. I discovered at the tender age of ten or younger that I’d developed a reasonably good romantic singing voice, and that I aspired to follow in the theatrical footsteps of Harry Lillis Crosby (“Bing” to you) when I grew into manhood. I only had eyes for Bing at the time, and had little interest in an upstart named Sinatra. My cousin Marsha had developed something of a teen crush on Frank, but the purity of my ten-year-old “vision” would only allow for the more traditional warbling of “the old groaner.”

I had first encountered the enigma called Sinatra a year earlier during a “live” television broadcast of Thornton Wilder’s classic Our Town. The highly publicized and significant tv production was to be aired in “Living Color” on NBC. The famous story was given a new wrinkle for television. It was to be an entirely new and original musical production with words and music written expressly for the show by the popular composing team of Sammy Cahn and James (Jimmy) Van Heusen. Cahn and Van Heusen had become Sinatra’s composers of choice, and their tunes for the program went on to achieve their own “star” status on America’s Hit Parade. Van Heusen, whose real name was Chester Babcock and who took his stage name from his favorite shirt, was often spoofed by friend Bob Hope when the comedian used the song writer’s real name as his character name in some of the Crosby and Hope “Road” pictures for Paramount.

Our Town premiered as a part of the “Producer’s Showcase” series on September 19, 1955, and featured Paul Newman as George, Eva Marie Saint as Emily, and Frank Sinatra as “The Stage Manager.” The program contains the only known visual record of Paul Newman singing. Network news commentators and personality hosts all stood gleefully in line to extract interviews from the cast and, in particular, from Frank Sinatra whose recently revitalized career offered him the rare opportunity to introduce four new songs for the production. These included the title song from the production, “Our Town,” as well as newly realized Sinatra standards such as “Look To Your Heart,” “The Impatient Years,” and the program’s mega hit tune, “Love and Marriage.” The color elements of the original program seem to have been lost over the ensuing years, but a fine black and white “kinescope” survives, and attests to the still poignant drama of this unique interlude in early television history and development.

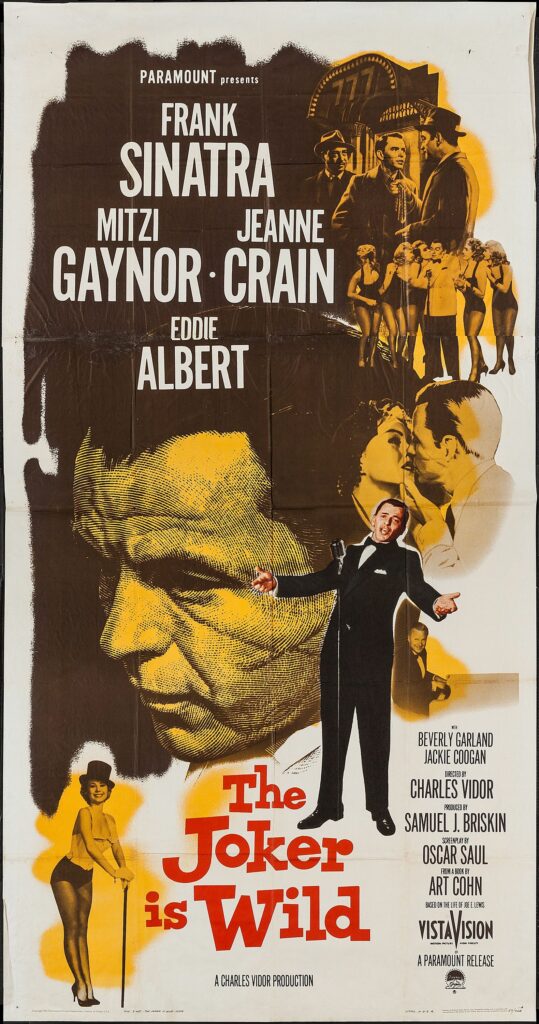

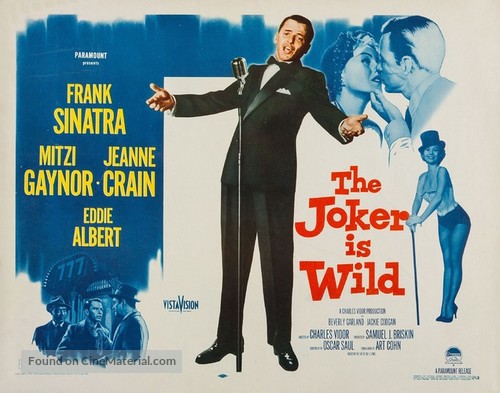

Now, I’d seen the coming attractions at The Benner Theater for a new film biography “Coming Soon,” and decided in 1957 to go see The Joker Is Wild starring Frank Sinatra as comedian Joe E. Lewis. It was a wonderful experience which further intoxicated my growing dreams of pursuing a show business career as a singer, further reinforced by Sinatra’s screen performance of a new Cahn and Van Heusen song called “All The Way.” The film had originally been produced as All The Way, which must have exasperated Cahn and Van Heusen when their carefully fashioned title tune was sung for a film now titled The Joker Is Wild. Nevertheless, that song would come to play an important role in the transition of my own musical tastes.

Wedged somewhere between my growth from childhood to maturity came a transitional period often referred to as one’s teenage years. It was during this often troubling period that I came to fall in love with the voice of a young folk/rock singer named Jimmie Rodgers. I had left Crosby behind, and was purchasing every recording I could find by Rodgers. “Honeycomb,” “Kisses Sweeter Than Wine,” and “Oh-Oh, I’m Fallin’ In Love Again” became my favorite songs of this era, and I played them quite literally until the grooves on the recordings had been worn to dust. I was the singer’s biggest fan from 1957 until somewhere midway through 1960 when a curious thing happened. I was fourteen years old. I became aware of politics for the first time, adored Jack Kennedy and Camelot, and wistfully longed for adulthood to consume me. I was conspicuously aware of searching for more evolved, mature role models. As an aspiring singer, I began looking for a new musical influence from which to pattern my own vocal development. In the back of my ever curious, expanding mind and experience, I heard once again the rich, warm, deep strains of “All The Way,” as interpreted by Frank Sinatra. The “single” of the recording was the first record I’d ever purchased as a determined young eleven-year-old, transitioning to adulthood in 1957. That record came back to haunt me in the Fall of 1960, and would come to have a profound effect on the meaning and direction of my subsequent life.

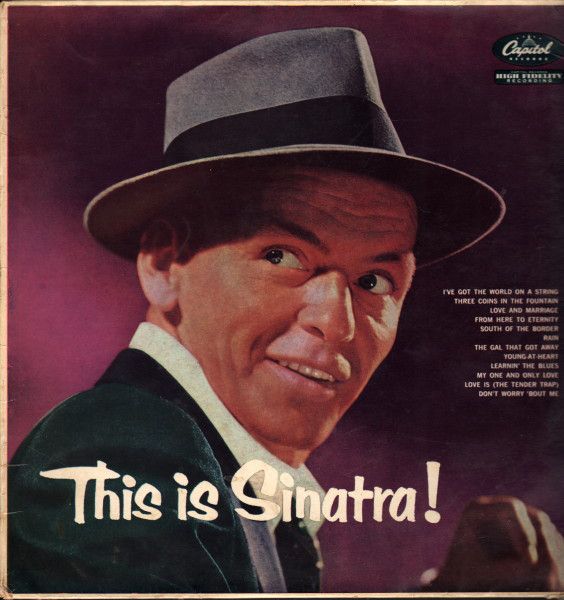

One of the first record albums I ever purchased, after Johnny’s Greatest Hits by Johnny Mathis, and Music From One Step Beyond by Harry Lubin, was This Is Sinatra, followed quickly by This Is Sinatra Volume Two. I’d borrow a little portable record player each weekend from my neighbor, Art Soren, and play these Sinatra recordings over and over again throughout these now interminable weekends for my parents. That was it. I was in love. I wanted to BE Frank Sinatra. Sinatra’s friendship with Jack Kennedy only served to solidify my connection with the artist. As for the singer’s validity and credentials as an actor in the motion picture community, these early years in which my cinematic and musical tastes were rapidly developing became integral to my adult years as a writer. I was growing ever more serious, both about my adoration of Sinatra and the career path that would subsequently guide the direction and meaning of my life. This, then, was no simple “idol” chatter.

Of Sinatra’s progression from the bobby sox idol of his day to a motion picture star, his evolution was alternately maddening and unforgettable. It seemed inevitable that the crooning recording artist, first for Harry James and then for Tommy Dorsey, would eventually wind up appearing on movie screens across America. How to cast the youthful singer, however, became problematic, as his squeaky clean image with drooling teenage girls allowed for little more than fluff appearances in those early war-related years.

His first appearance came in 1941 with a minor effort produced by Paramount entitled Las Vegas Nights. This decidedly less-than-stellar endeavor remains notable only for its inclusion of an appearance by the Tommy Dorsey band, and its fledgling male vocalist singing Ruth Lowe’s classic lament for a woman who had lost her husband to war, “I’ll Never Smile Again.” MGM’s Ship Ahoy followed a year later in 1942 as a thoroughly innocuous musical for dancer Eleanor Powell, and comedian Red Skelton. Tommy Dorsey and his band appeared once again, accompanied by an ambitious crooner named Sinatra who would sing “The Last Call For Love,” and “Poor You.” Moving over to Columbia Pictures in 1943, Sinatra would perform a single tune, but what a tune. Sans the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra, he sings Cole Porter’s “Night And Day” for an otherwise forgotten Ann Miller vehicle titled Reveille With Beverly. Later the same year, Sinatra would co-star with Michele Morgan and Jack Haley in his first somewhat “starring” screen role in Higher And Higher (which he would later refer to as “Lower And Lower”), an ineffectual musical “comedy” produced for RKO. He plays a boy-next-door type who, not surprisingly, is actually Frank Sinatra. He loses the girl to “the tin man,” but virtually steals the show when crooning “I Couldn’t Sleep A Wink Last Night,” and “This Is A Lovely Way To Spend An Evening.” In one memorable sequence, he sings standing by a piano played by Rick Blaine’s Casablanca accompanist, Dooley Wilson. RKO managed to step lively when preparing their star’s next screen fling, Step Lively, co-starring Gloria De Haven and future United States Senator George Murphy. As innocuous as its predecessor, the more white than black comedy featured Sinatra as a young country bumpkin aspiring to conquer Broadway as a budding playwright. The music, however, overwhelmingly steals the show as Sinatra’s stunning interpretation of “As Long As There’s Music” dominates the picture’s legacy.

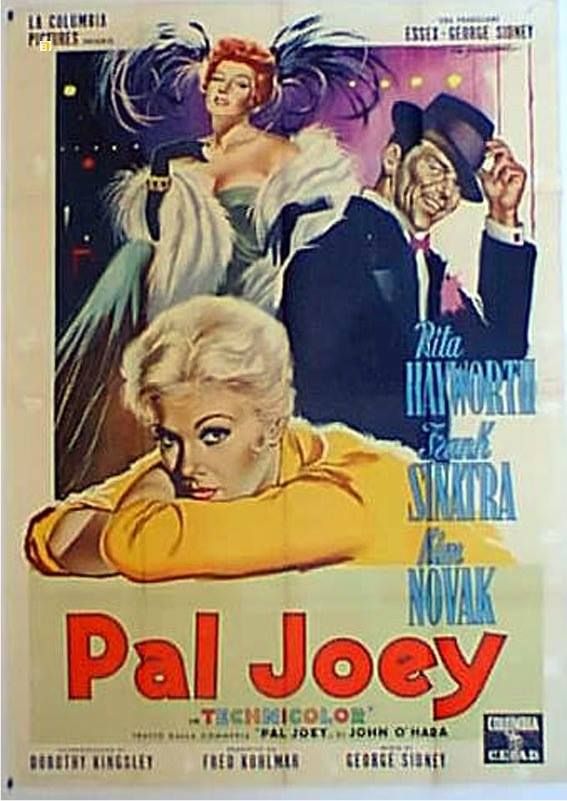

It was only natural, and clearly inevitable, that Sinatra would soon move over to the reigning bastion of musical comedies, Metro Goldwyn Mayer and, in 1945, the studio released its blockbuster extravaganza, Anchors Aweigh starring Sinatra, along with his new partners, Kathryn Grayson and Gene Kelly. While no more sophisticated in his characterizations than in his previous roles, Sinatra had dramatically grown in importance to Tinseltown, earning a coveted starring role in a huge MGM musical featuring outstanding production values, and memorable songs. Adding his usual class to the presentation was the incomparable classical conductor Jose Iturbi who was, in his own right, becoming a highly dignified staple of the MGM musicals. It is Gene Kelly, however, who steals the show in his immortal dance duet with Jerry The Mouse from the Tom and Jerry cartoons. Sinatra’s defining moment in the cherished musical comes with his tender performance of “I Fall In Love Too Easily” by Jule Styne and Sammy Cahn. The film was helmed by George Sidney who would direct a decidedly different, far more artistically developed Sinatra a mere twelve years later in Pal Joey for Columbia.

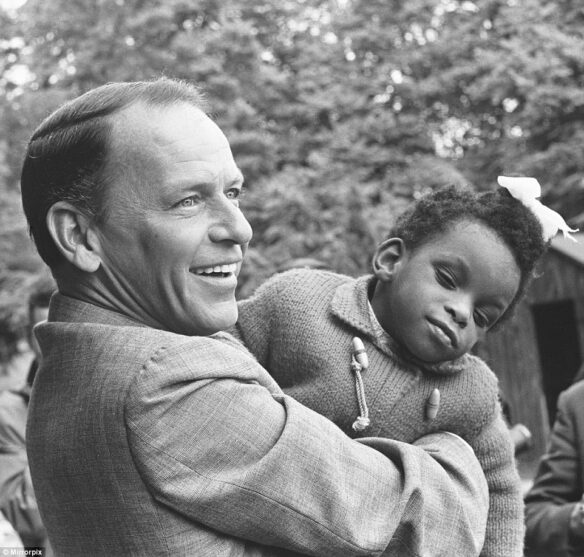

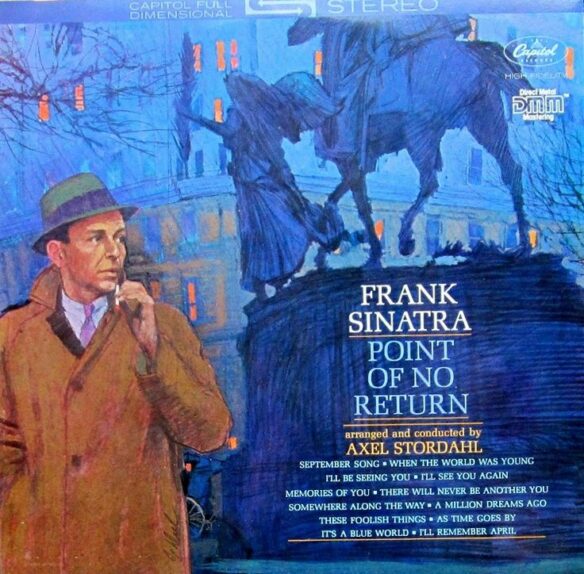

RKO would produce, perhaps, the most influential and important Sinatra film of the decade later in 1945. The House I Live In, written by blacklisted writer Albert Maltz (one of the celebrated “Hollywood Ten” accused by Senator Joseph McCarthy), and directed by Mervyn LeRoy, was a powerful ten-minute short focusing on racial intolerance in America in which Sinatra, playing himself, records in a studio, blithely unaware of the street kids in the adjoining alley terrorizing another boy from a different ethnic background. Sinatra’s heartfelt plea to the youngsters for love and tolerance won the singer and the film a special Academy Award. Sinatra, known even then for his liberal politics, had been visiting area high schools preaching racial acceptance and harmony. These caring, selfless acts on the part of the singer prompted the studio to produce its celebrated, Oscar winning short film. Performing with arranger/conductor Axel Stordahl, Sinatra sings “If You Are But A Dream,” and the stunning title anthem by Earl Robinson and Lewis Allan.

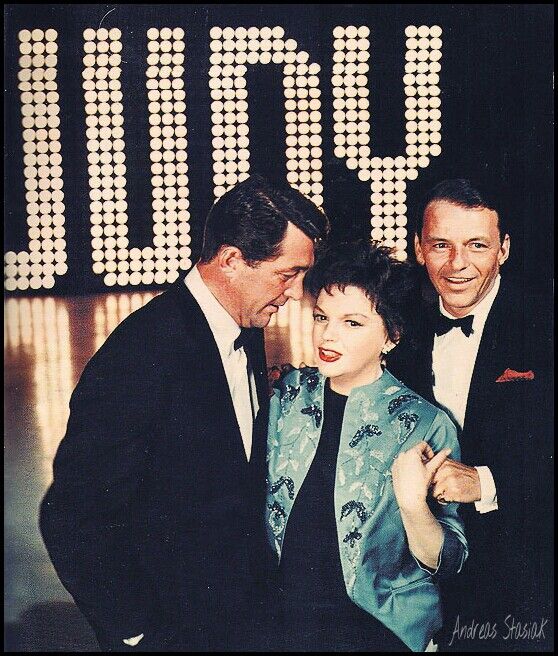

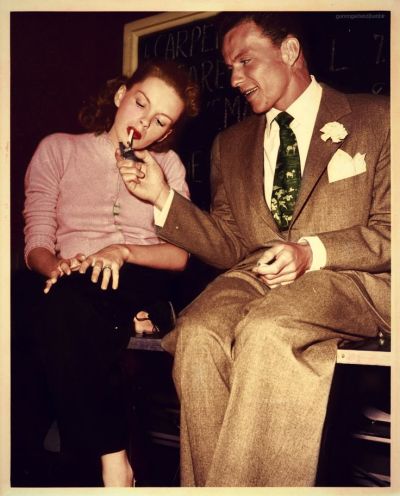

In 1946, MGM produced one of their most lavish and respected musicals. Till The Clouds Roll By, inspired by the life and music of composer Jerome Kern, featured a vast ensemble of the studio’s musical contract players in separate set pieces and production numbers, including Judy Garland, Lena Horne, Kathryn Grayson, Van Johnson, June Allyson, and Dinah Shore. The film’s climactic masterpiece, however, remains the brilliant performance by Frank Sinatra, dressed in a stunning white tuxedo, echoing the pain of millions, in a spectacular rendition of Kern’s superb “Old Man River” from Show Boat.

Sinatra’s next starring vehicle for MGM would be the delightful It Happened In Brooklyn, released by the studio in 1947, pairing Sinatra once more with Kathryn Grayson, along with Jimmy Durante and his later Rat Pack pal, Peter Lawford. Two army buddies, stationed in England, return to the United States at the conclusion of the Second World War, and vie for the attentions of the proverbial girl next door. Naïve, but utterly charming, the Sinatra vocals include “Time After Time,” “I Believe,” “It’s The Same Old Dream” and, in a memorable duet with Durante in which Sinatra wonderfully emulates the elder statesman of comedy, “The Song’s Gotta Come From The Heart.”

Sensing the need to expand his artistic horizons, Sinatra took a gamble with his next picture, playing his first somewhat dramatic part in RKO’s tale of faith and spiritual miracles. The Miracle of the Bells, a deeply moving story of a young actress whose untimely death precedes the opening of her first starring role in a film about Joan of Arc, premiered in 1948. Fred MacMurray stars as a hungry studio publicist trying to keep the producers from shelving the picture after the death of its star. Alida Valli (The Third Man) stars as Olga Treskovna, the film’s ill-fated star, along with Lee J. Cobb as Marcus Harris, the conflicted studio head trying to save his studio. Sinatra appears in a brief, but pivotal and moving performance as Father Paul, the young parish priest whose small Coaltown, Pennsylvania church has been chosen as the location of Olga’s final farewell. Sinatra sings the deeply moving “Ever Homeward,” written by Kasimierz Lubomirski, along with Jule Styne and Sammy Cahn.

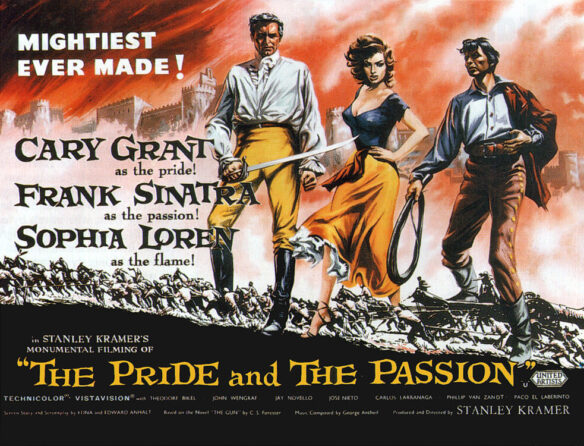

MGM’s The Kissing Bandit, released in 1948, found the crooner adrift once more in a likeable, if sappy variation of The Pirate in which Gene Kelly was mistaken as a notorious buccaneer. Sinatra, a milquetoast business school graduate from Boston, finds himself in old California where he impersonates a kissing bandido in a gang once run by his late father. The film, while colorful and entertaining, has been acknowledged by Sinatra as the least favorite of his various screen roles (together with his performance as Miguel in The Pride and The Passion. The exquisite Kathryn Grayson co-starred once again as his romantic lead.

Take Me Out To The Ball Game from MGM in 1949 was the second and, perhaps, the weakest of the Frank Sinatra, Gene Kelly musical collaborations, featuring the pair of unlikely sports figures, playing both baseball and vaudeville while simultaneously wooing Esther Williams and Betty Garrett. To Sinatra’s credit, the singer underwent punishing dance steps and routines under the supervision of Kelly in both this film, as well as their earlier collaboration, Anchors Aweigh, and emerged a highly professional dance partner for the more remarkably skilled hoofer. Their next collaboration, however, would become the most memorable of their three dance films together.

On The Town, produced by MGM in 1949, directed by Gene Kelly and Stanley Donen, with music by Leonard Bernstein, and lyrics (as well as screenplay) by Betty Comden and Adolph Green became the first musical film ever to shoot on actual locations, rather than indoor stages and sets, in the city of New York. The city, its streets, subways, skyscrapers and bustling landscape were as much the stars and personality of the beloved musical as were its human protagonists. New York, with its exuberance, excitement, and pulsating electricity, provided the vibrant backdrop and story of three sailors on leave in Manhattan who discover romance, music, and adventure along Rockefeller Center and The Great White Way. The incomparable vitality of Kelly and Donen’s direction and choreography, together with spirited live on location performances by Kelly, Sinatra, Jules Munshin, Ann Miller, Betty Garrett, radiant Vera Ellen as the ever elusive “Miss Turnstiles,” the music of Leonard Bernstein, and the shattering steel and chrome exhilaration of the world’s greatest city, joyfully combined to create a truly one of a kind motion picture musical experience.

RKO’s embarrassing Double Dynamite co-starring Jane Russell and Groucho Marx followed in 1951, nearly ending the long careers of each of its players, but Sinatra’s next performance, though largely forgotten today, would powerfully shape the dramatic career path and stature of its star for virtually the remainder of his life.

Frank Sinatra was going through the worst period of his life. He had grown beyond the adoration of his one-time bobby soxer fans. MGM had tired of his seeming one-dimensional screen persona, although they had helped to fashion and perpetuate it…and, while trying desperately to resuscitate his singing career, his vocal chords had hemorrhaged, leaving him to wonder if he’d ever sing again. His cronies, sensing the end of his career, deserted him and wouldn’t pick up the phone to take his calls. With professional medical care and prescribed rest, the voice eventually returned, but Sinatra remained a professional hot potato in Hollywood.

Meet Danny Wilson, released in 1951 by Universal International Pictures, should have changed the singer’s fortunes but, astonishingly, it didn’t. As Danny Wilson, Sinatra plays a brash, hip performer with ties to the mob. This was not the Sinatra of old but, rather, a self-assured, dramatic powerhouse whose explosive acting and mature vocals set the stage for virtually everything that would establish his familiar persona in years to come. The baby fat, both physically and vocally, had disappeared, replaced by a lean and confident cocoon preparing to give birth to the most remarkable singer of the Twentieth Century. Sadly, neither the film’s budget nor cast prompted anything more than unremarkable “B” film reviews. Directed by Joseph Pevney, with an original screen play by Don McGuire, Meet Danny Wilson introduced a brand new, revitalized Sinatra to an audience that simply didn’t care. Had audiences gone to see this little film with overpowering aspirations, it might not have taken another two years for Sinatra to return to the top.

While traveling with then wife Ava Gardner for location shooting in Africa, Sinatra seemed out of place and uncomfortable. He was simply along for the ride. Gardner was starring with Clark Gable and Grace Kelly in John Ford’s remake of an earlier Clark Gable vehicle, Red Dust. For Mogambo, Gardner was playing the role earlier essayed by Jean Harlow in the MGM 1932 original. A novel by writer James Jones was being prepped for filming back in the states, and its casting was the hottest ticket in Hollywood. From Here To Eternity had taken the country by storm, and director Fred Zinnman was busily searching for the actors who would grace the most highly anticipated film in years. The bestselling novel concerned the tumultuous lives of army personnel in Hawaii prior to the infamous attack on Pearl Harbor. Among the characters populating James Jones’ novel was a hot headed, arrogant little Italian private named Angelo Maggio. Sinatra read the novel, and identified so strongly with the character of Maggio that winning that role in the film had obsessed him. He believed that he WAS Maggio, and that no one else could play the part. Zinnman wanted no part of him, but Sinatra persuaded Gardner to talk to Harry Cohn, the Columbia Pictures studio head who had wisely purchased the rights to film the novel. To virtually everyone’s astonishment, Sinatra’s screen test won him the role and what followed became the stuff of cinema legend. Sinatra became Private Maggio. He ate, slept, and breathed the characterization. In the film’s pivotal scene, Sinatra is brutalized by Ernest Borgnine in the company brig. He escapes imprisonment in the back of an army truck, only to fall out of the vehicle and bounce cruelly along the darkened road. He crawls in agony to his friends (Montgomery Clift and Burt Lancaster) where he dies in Clift’s arms. That performance and, in particular, that sequence won him the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor of the year. Suddenly, everyone in town was looking at him with new eyes. Those who had written him off and forgotten him were now knocking at his door, begging for his attention. He was back. Sinatra had returned, and he would become bigger than ever.

Hungry for meatier roles, along with a desire to effectively immolate his former screen persona, Sinatra next enacted one of his most frightening performances and, indeed, one of the most chilling performances in cinema history…that of the psychotic assassin John Baron in Suddenly. Released in 1954 through United Artists, and directed by Lewis Allen (The Univited), Sinatra plays a vicious killer for hire who, with his lethal associates, arrives in the innocuous California community of Suddenly, where he toys sadistically with conservative, old world ideals and balances while meticulously plotting to kill the President of the United States whose train is scheduled to stop in the quiet suburban community. America, in the middle 1950’s, still reeling from the subversive shock of war in which its traditional values and morality were challenged and nearly decimated by Hitler and his conquering armies, has returned to the complacency and isolationism inherent in world weary societies, tired of war and seared by pain. Its citizens ache for the simplicity of an idealistic culture painfully absent from the imposing international landscape. Into this hedonistic plateau arrives a cold-blooded assassin whose narcissism explodes in ranging contempt for the human Ostrich community refusing to lift up its collective head from the sand. Baron, too, has been irrevocably scarred by the brutal reality that no man or country is an island unto himself, but his insecurity and fear have been manifested in aggression, suspicion and the seething hatred of an animal cornered in ever diminishing space. His ugly contempt for humanity shocks his hostages into seizing once more their emasculated strength, embracing their beliefs, and standing firm in the face of fear. Their unity defeats Baron, exposing his naked cowardice and callous contempt for peace. Sinatra delivers a fiercely frightening performance as a wounded psychotic, a coward with a gun, finally crumbling in both humiliating and numbingly terrified defeat. Standing against him in accumulated courage and resolve are Sterling Hayden, James Gleason, Paul Frees (War of the Worlds and The Thing From Another World) and Nancy Gates who would appear once again with Sinatra four years later as Arthur Kennedy’s mistress in Some Came Running.

Young At Heart, released by Warner Bros in 1955, was based upon Fanny Hurst’s “Sister Act,” which had been filmed previously by the studio as Four Daughters. Sinatra plays “stumble bum Barney Sloan,” a talented song writer plagued by torturous doubt and self defeating insecurities whose insertion into a traditional middle America family wreaks havoc upon their naïve confidence and values. His edgy, conflicted performance as a ”victim” of bad breaks and circumstances beyond his comprehension, echoes perfectly the cynical interpretation of a talented “loser” earlier enacted by John Garfield in the original production. Doris Day is the uncomplicated “girl next door” he falls in love with and who, ultimately, saves him from his personal demons. Sinatra escapes the fate rendered Garfield at the sad conclusion of the original version, although his performance is every bit as edgy and emotionally vulnerable. The film gives both stars an opportunity to shine musically, and Sinatra delivers definitive, unforgettable performances of “One For My Baby, “Just One Of Those Things,” “Someone To Watch Over Me,” the haunting “You My Love” (in his single screen duet with Day), and the hit title theme, “Young At Heart.”

Sinatra next essayed the role of an amusingly cynical young doctor in Stanley Kramer’s ensemble directed Not As A Stranger (United Artists, 1955), based upon the bestselling novel by Morton Thompson, with a screenplay by Edward and Edna Anhalt. A young, idealistic doctor (Robert Mitchum) nobly climbs the medical ladder of success, sacrificing all human interaction to the aspirations of his clinical beliefs, realizing nearly too late that the frailty of human emotion is as essential a component as medical knowledge in healing the sick. With an all-star cast, including Mitchum, Olivia DeHavilland, Charles Bickford, Sinatra, Lee Marvin, Broderick Crawford, and Lon Chaney, Jr as Mitchum’s alcoholic father, the film is interesting but, ultimately, flawed as Mitchum’s lead character is written and portrayed as an entirely unsympathetic son of a bitch, failing virtually everyone whose love and support he callously abandons and betrays in the name of blind ambition.

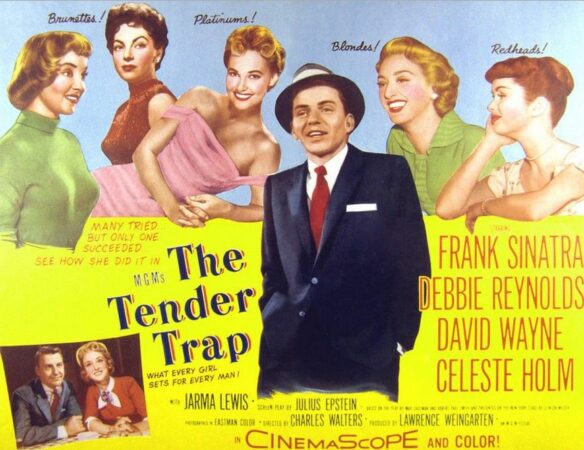

MGM’s The Tender Trap, released in 1955, is an innocuous bit of sexist fluff based upon a Broadway play by Max Shulman, the celebrated creator of The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis. Sinatra stars this time as theatrical agent Charlie Reader, a womanizing bachelor romancing multiple secretaries and starlets until he meets Julie Gillis (no relation to Dobie), charmingly portrayed by Debbie Reynolds. David Wayne appears as his best friend, frustrated by the perceived restrictions of a perfect marriage, and longing to emulate his swinging pal. The wonderfully sophisticated Celeste Holm plays Sinatra’s wise, if ultimately jilted girlfriend of convenience. Predictably scripted, The Tender Trap offers comparatively little in the way of originality. Its surviving strength is in its remarkably memorable opening and closing sequences, particularly the former, in which Sinatra emerges from the distance on an empty, barely camouflaged soundstage, adorned in his signature sports jacket and designer hat, swaying persuasively in rhythmic, self-assured confidence as he flirts mesmerizingly with the camera while singing “Love Is The Tender Trap”. The musically evocative, sexually intoxicating introduction to an otherwise unimaginative bedroom farce, remains both the film’s and its star’s character defining moment of the decade.

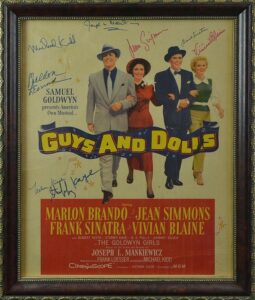

Samuel Goldwyn’s lavish Technicolor production of the Broadway smash Guys and Dolls, released the same year, is an ambitious, if slavishly stage bound version of the Abe Burrows hit (based upon “The Idyll Of Miss Sarah Brown” by Damon Runyon) musical with memorable songs by Frank Loesser. Unimaginatively directed by the usually gifted Joseph L. Mankiewicz, this colorful screen translation seemed mis-guided and miscast by period star value, rather than genuine musical talent. Starring the superb Marlon Brando in one of his oddly ineffectual early performances, the otherwise astonishing actor plays the lead role of Sky Masterson in a musically impotent interpretation that begs credibility. Playing the second banana role of ultimate “stooge,” Nathan Detroit, is Sinatra who, at this stage of his re-emerging career, should have played the lead. Sinatra is said to have referred to Brando during the production of the film as “mumbles,” while the method actor delivers a nearly catastrophic performance of the show’s most memorable tune, “Luck Be A Lady.” Guys and Dolls is remembered more as a curiosity, sadly, than as a successful screen visualization of a classic Broadway show.

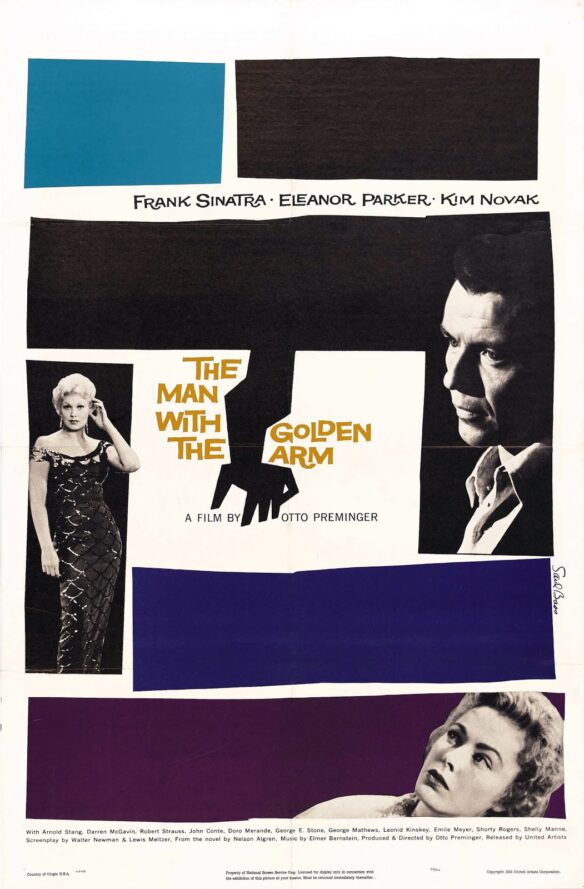

Sinatra would fare significantly better in his next film, Otto Preminger’s explosive production of Nelson Algren’s novel, The Man with the Golden Arm. Released in 1955 by United Artists, Sinatra’s title role in this unflinching look at the world of drug addiction was one of the first American films to explore the raw underbelly of substance abuse. Still shocking today, the film was revelatory and unimaginably horrifying upon its controversial release in the mid-Nineteen-Fifties. With a pounding, electrifying jazz score by composer Elmer Bernstein, Sinatra’s stunning performance as a “dealer” of cards in backroom games and marathon betting sessions won him another Oscar nomination for Best Actor. Sinatra visited a variety of drug rehabs and sanitariums while researching the part, witnessing firsthand the horrors of drug addiction. It was an experience that would haunt him in years to come, nearly severing his long friendship with Sammy Davis, Jr., when the gifted performer briefly succumbed to the drug culture of the Sixties. Sinatra’s performance in a key sequence in which Frankie Machine is locked in a room, forced to go “cold Turkey” in order to kick his addiction alone, writhing and screaming in physical torment on the floor, is nearly unwatchable even by modern standards in its violent ferocity and realism. Kim Novak co-stars with Sinatra as an understanding neighbor secretly in love with dealer, while deservedly acclaimed actress Eleanor Parker is a revelation as his sick, manipulative wife. The role would become the defining dramatic performance of Sinatra’s screen rebirth.

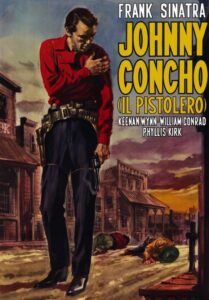

His next starring role would find Sinatra in a courageous performance as a young coward in one of the first Freudian westerns, the failed yet ambitious story of Johnny Concho. Released by United Artists in 1956, the complex tale concerned a bully riding on the reputation of his gunslinger brother, until his infamous sibling is killed in an armed confrontation, and Johnny is left exposed and vulnerable. Naked and ridiculed by the community he once lorded over, the young sibling must prove to the town and his girl that, in the face of avenging brutality by gunslingers and bandits overriding the quiet community, he is a man. The score by Nelson Riddle is subtle, yet effective, producing the single “Wait For Me,” a brooding, evocative hit for the singer.

His next film, a starring role in one of the most delightful musical comedies of the fifties, would prove a lyrically defining moment for the actor and singer. MGM’s big budget, glossy remake of the Broadway hit and Oscar winning comedy The Philadelphia Story (Katherine Hepburn’s “comeback” vehicle) provided the basis for the immortal Cole Porter’s final score. High Society, produced and released by MGM in 1956, was among the most delightful, sophisticated, effusively joyous musicals of the decade. Pairing Sinatra with his lifelong idol, Bing Crosby, for the first time on screen was a major coup for the studio, for there were no more important musical stars in Hollywood at the time of this inspired collaboration. Joining forces with Sinatra and Crosby were the reigning dramatic queen of the film industry, Grace Kelly, and jazz musical legend Louis Armstrong. With Crosby in the lead as C.K. Dexter- Haven (in the role originally enacted by Cary Grant), Grace Kelly as the rich, untouchable Tracy Samantha Lord (the role first played by Hepburn in her career-saving performance), and Sinatra (co-starring once again with the wonderful Celeste Holm) as Macauley “Mike” Connor (originally played by Jimmy Stewart), the film is a musical gem. Heralded as Grace Kelly’s final screen performance before assuming the real-life royalty persona and duties as Princess of the Principality of Monaco, High Society is a joyous marriage of music, wit, and sophistication. Both Crosby and Kelly won a gold record for their million selling recording of “True Love,” while Sinatra and Crosby literally steal the show with their incomparable rendition and performance of Cole Porter’s alcohol induced set piece, “Well, Did You Evah?”… a classic screen duet that never fails to invite warm smiles and magical, delectable, happiness and delight.

Among the strangest and, perhaps, most ill-advised films in the Sinatra canon was Stanley Kramer’s ambitious take on the Peninsular Wars and the Napoleonic campaign in Spain, during which Spanish peasants and freedom fighters courageously fought the French with passionate resistance. An abandoned cannon, left by Spanish soldiers under attack by advancing French forces, is a valued prize coveted by both the peasants and a British captain eager to secure its weaponry. Cary Grant co-starred with Sinatra and Sophia Loren in The Pride and the Passion, released by United Artists in 1957. The finished film was a colorful extravaganza, but Sinatra seemed uncomfortable in his performance as Miguel, a Spanish rebel, and his accent appeared both forced and at times awkward. While the actor’s efforts were noble and sincere, the actor himself regarded his performance as embarrassing and among his least favorite roles. Kramer may have overextended himself with this massive, yet somehow lethargic production, which seemed overburdened at times by the weight of its location shooting and self-important dialogue. Consequently, the film is often more ponderous than impactful and is remembered more as a curiosity than an epic.

Despite an awkward start to the year, however, Sinatra’s next two films would join the most iconic, beloved productions of his motion picture career. The Joker Is Wild provided the actor with one of his most ingratiating performances. Based upon the popular book by Art Cohn, the film recounts the turbulent life story of standup comedian Joe E. Lewis. Lewis is beginning a promising concert and recording career as a singer when his throat is slashed by rival nightclub owners, retaliating for his defection to another club. His vocal chords cut and permanently damaged, Lewis can no longer sing. Sophie Tucker finds the savaged performer hiding beneath the greasy camouflage of a clown’s makeup on a burlesque stage, and helps him to find an unsuspected calling. His cynical wit and comic swipes at his own misfortune lead him on a secondary path as a celebrated, yet volatile, comic whose temper often strains the patience of those who love him. His tantrums and alcoholic binging ultimately decimate the tenuous bonds of both love and friendship, leading to a final self realization that will either destroy him, or lead to his personal salvation. Sinatra is wonderful as the conflicted comedian whose real life friendship with the singer played an integral role in his seeking the role. Upon the film’s release by Paramount in 1957, Lewis remarked that “Frank had more fun playing my life than I had in living it.”

The film had originally been titled All The Way when production began, and Sinatra collaborators Sammy Cahn and James Van Heusen had been asked to pen the title song. However, after the song had been written and submitted, Paramount decided to revert to the original title of Art Cohn’s biography. The song remained in the picture although it could no longer be considered a “title” tune, winning an Oscar in the process, thereby becoming one of Sinatra’s most closely identified signature songs for the rest of his life. Directed by Charles Vidor, with a sterling cast that included Eddie Albert as his beleaguered long time pianist Austin Mack along with Mitzi Gaynor and Jeanne Crain as his battle scarred romantic leads, and the fabulous Beverly Garland as Albert’s caustic wife, the picture remains among the brightest lights in the singer’s dramatic film career. Interestingly, it was during the production of a key sequence in the film involving Sinatra and Mitzi Gaynor that Gaynor was asked to come in and audition for Richard Rodgers and Oscar Hammerstein who were casting the leads in their upcoming film translation of South Pacific. When Sinatra heard that Gaynor could not make the audition due to scheduling demands and conflicts imposed by the film’s director, Charles Walters, he instructed Walters to “just shoot around her.” According to Gaynor herself, it was thanks to Sinatra’s personal intervention that she made the audition and won the coveted role of Nellie Forbush in the 1958 Joshua Logan production.

Following on the heels of his enormous success as Joe E. Lewis, Sinatra next essayed, perhaps, the most iconic role of his career…that of Joey Evans, novelist John O’Hara’s despicable womanizer and cad, while everyone’s Pal Joey. Produced on Broadway in 1940 by Richard Rodgers and then partner Lorenz Hart, the modestly successful New York musical made a star of Gene Kelly in the lead performance. While Rodgers and Hart, along with O’Hara, envisioned Evans as a dancer for the original theatrical production, the suave heart throb became a singer when Columbia Pictures and director George Sidney offered the coveted role to Sinatra.The character of the “character” was softened somewhat for the screen version but Joey, although overwhelmingly charming, particularly to women, remained a narcissistic “louse.” The part was tailored perfectly to fit Sinatra’s post-comeback swagger and macho persona. Women adored him, and men wanted to BE him. As a wisecracking, romantic “user,” Sinatra fit Joey Evans like a well worn glove, twisting and manipulating everyone in his selfishly evolving web of deceit and personal aggrandizement. Aided and abetted by two of Columbia’s biggest female stars, Rita Hayworth and Kim Novak, Sinatra was at the peak of his heavily publicized, lecherously sophisticated charm and sensual appeal. Adorned in a white dinner jacket while seated on a revolving piano stool, his cocky, finger snapping, self assured rendition of “The Lady Is A Tramp” is as classic a male “temptress” in its imagery as John Travolta’s acrobatically sexual movements in Saturday Night Fever. Waving his fingers in the air, gently clutching a lit cigarette while singing and fondling the piano keys in rapturous romanticism, THIS was Sinatra at the pinnacle of his allure and success. If the film is deficient in any manner, it would be in the abandonment of a more elaborate musical finale than what ultimately appeared on the screen. Hayworth, a veteran “hoofer” and dance partner to both Fred Astaire and Gene Kelly, had rehearsed a complicated musical routine with Kim Novak for the climactic “What Do I care For A Dame” sequence with Sinatra. While Sinatra had himself performed many stylish, energetic dance steps with Gene Kelly over the years at MGM, he appeared unwilling to participate in an elaborate new choreographed sequence. Whether due to time constraints or growing insecurity about his earlier film career path, Sinatra chose a more simplistic, stylized treatment over the more ambitious choreography rehearsed by Hayworth and Novak. Sinatra needn’t have worried about his prowess as a dancer, however. Years later, after his abrupt retirement from the stage, he returned to television with a musical special entitled “Old Blue Eyes Is Back” in which both he and Gene Kelly sang a remembrance of their musical pairings called “We Can’t Do That Anymore,” all the while reprising their original dance steps and proving that they actually still could.

Kings Go Forth, released the next year by United Artists, and directed by Delmer Daves was a comparatively small film shot in black and white with Sinatra playing an essentially subordinate role opposite Tony Curtis and Natalie Wood in a World War Two drama concerning the dangerous love affair between an innocent Italian girl and a shallow soldier played by Curtis. Sinatra is torn between his love for Monique (Wood), and his friendship with Curtis. In the end, the film is a curiosity at best with a romantically unsatisfactory conclusion, and ineffectual hints of racial prejudice. It did, however, generate another modest hit recording for the singer in its title tune, “Monique” written by Elmer Bernstein with Sammy Cahn. Sinatra’s next role as a disillusioned soldier returning to his small Indiana home town after the war would yield one of his most remarkable, deeply sensitive performances, as well as an extraordinarily powerful motion picture.

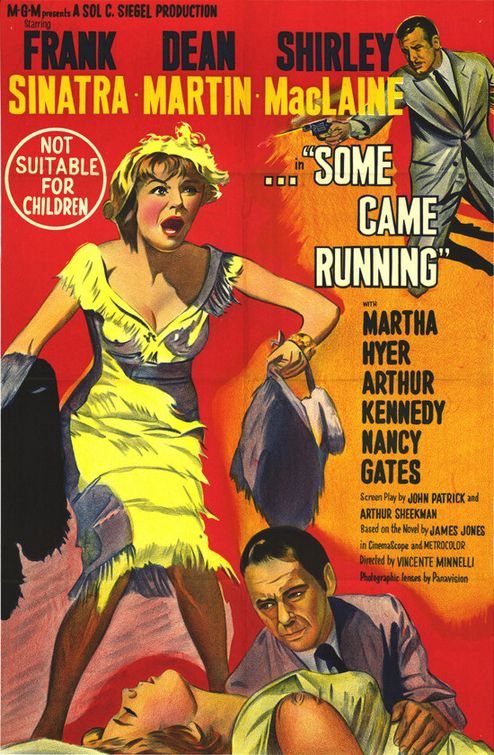

Vincente Minnelli was known primarily as a director of musicals, and was MGM’s premier song and dance interpreter. He would, however, wander off into new areas from time to time and work on some notable dramas. His non-musical films for the studio were among MGM’s dramatically finest, and included such remarkable films as The Bad And The Beautiful, Madame Bovary, and Lust For Life (the latter two films featuring brilliant scores by three-time Oscar winning symphonic composer Miklos Rozsa.) In 1958 Minnelli directed one of the most compelling dramas of his distinguished career. Some Came Running, based upon the novel by James Jones, would be Sinatra’s second involvement with the author of his Oscar-winning characterization in From Here To Eternity. Once again, he is an enlisted soldier in the Second World War. This time, however, he is a disillusioned veteran returning home to a small town in Indiana. He is accompanied on his Greyhound bus trip by a floozy he drunkenly picked up in a bar along the way. As interpreted by Sinatra, Dave Hirsh is a world weary soldier torn between several worlds, searching for his roots as well as a starting point from which to begin again. He is a writer whose single published novel caused a minor stir upon its publication, but whose creative well has seemingly run dry. Punctuated by composer Elmer Bernstein’s lush, passionate score, Some Came Running is a tale of loneliness, seething anger, frustration, and sexual repression longing for release. In his first of many later “Rat Pack” pairings with Sinatra, Dean Martin scores as an alcoholic professional gambler named Bama Dillert who hooks up with, and befriends Hirsh. Shirley MacLaine is wonderful as Ginny Moorehead, the sweet “hooker” who wants only to “love and be loved” by Dave, while Martha Hyer quietly ignites her surroundings as a sexually inhibited school teacher encouraging Sinatra to begin writing again. Rounding out the outstanding ensemble cast is the always reliable Arthur Kennedy as Sinatra’s older brother, a traditional small town moralist who wishes that Dave had stayed on the bus. Some Came Runnng offers Sinatra an opportunity to play a scarred artist reaching out for beauty and meaning in his life following the war, while MacLaine’s bittersweet, Oscar nominated performance is heartbreaking in its fragile, often simple humanity. The stunning conclusion of Some Came Running brings each of its deeply flawed characters to their inevitable ends, and beginnings with, perhaps, a wiser appreciation for what lies ahead. This is a superb, often underappreciated, motion picture with unforgettable characters, performances, and the eloquent writing of author James Jones.

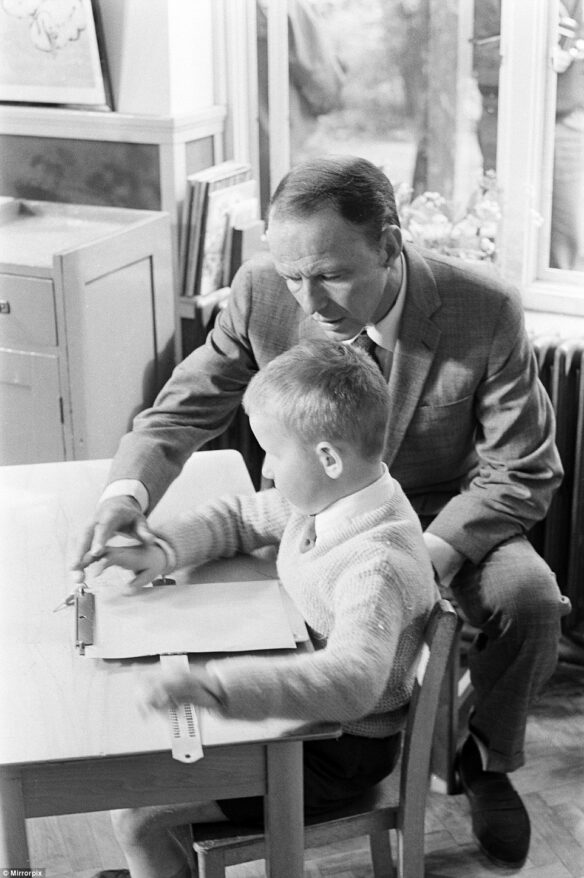

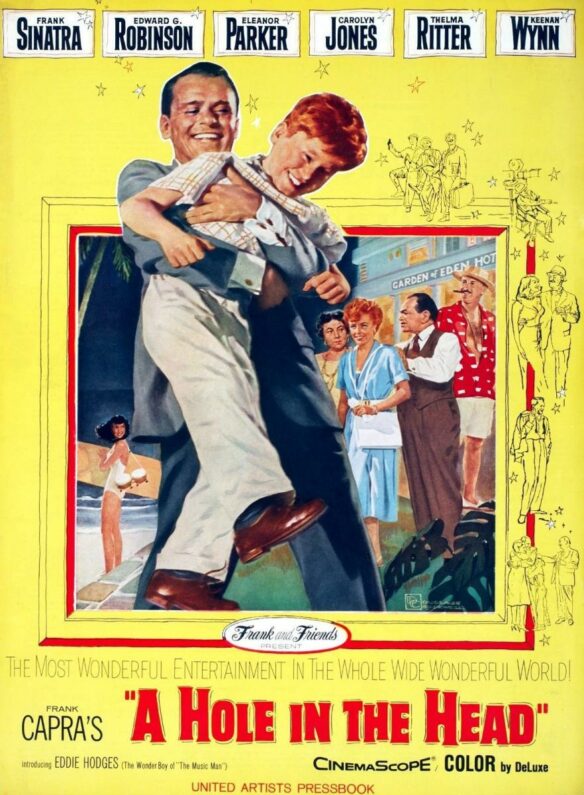

The years between 1957 and 1962 were, perhaps, the most creatively fertile for Frank Sinatra as an actor, and his next film would further demonstrate his ever-unfolding artistic talent and expressive range. A Hole In The Head (United Artists, 1959) features the actor as Tony Manetta, a down on his luck dreamer, and is among Sinatra’s most charming and endearing characterizations. Manetta owns a small, quirky hotel filled with equally quirky guests in a low rent district of Miami Beach, Florida. He is a wistful widower living with and raising his young son, Ally (played by Eddie Hodges) on the grounds of a decidedly “down scale” rental facility. Tony longs to escape the sordid confines of his surroundings, and “hit it big” one day. As reality closes in and foreclosure threatens, Tony reaches out to his older brother, Mario, and his wife (wonderfully played by the delightful Edward G. Robinson and Thelma Ritter) for money. Into this mix comes a beautiful widow played by the enchantingly versatile Eleanor Parker whose frightening performance as Sinatra’s conniving wife in Otto Preminger’s The Man With The Golden Arm would ordinarily have led him to run very far from her character, Mrs. Rogers. Sinatra is both entirely sympathetic and ingratiating in his love for his little boy, and his seemingly unlikely ambitions. His desperation and ultimate despair at the races as he gambles and ultimately loses the money that might have renewed his hotel lease is painted poignantly upon his face and emotional vulnerability. As so eloquently written by Sammy Cahn and James Van Heusen, he has “High Hopes” for “All My Tomorrows.” As directed by one of the screen’s greatest, most revered and influential directors, Frank Capra’s “American Dream” is lovingly exhibited here in one of his last motion pictures, proving that just when you think that all is lost…It’s A Wonderful Life after all. Capra was scheduled to direct Sinatra once again in a proposed screen biography on the life of comedian Jimmy Durante with Dean Martin as the legendary comic, and Sinatra as his partner but, sadly, the project was never realized.

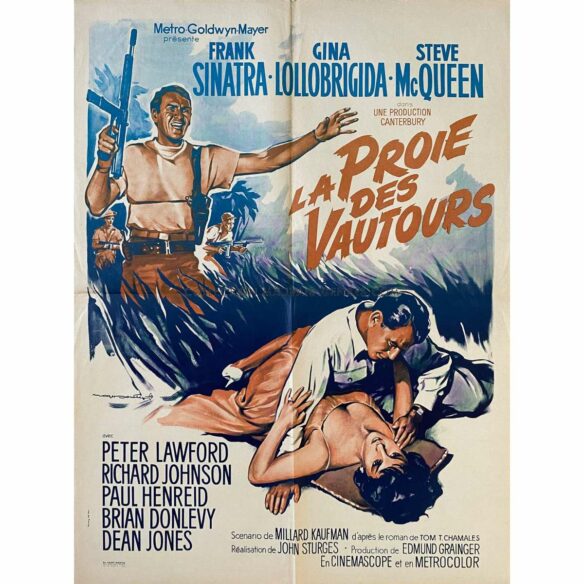

A private disagreement with cherished friend Sammy Davis, Jr. led to a creative opportunity for another young actor in Sinatra’s next film, Never So Few, released by MGM in 1959. Davis had been signed to play the role of Sinatra’s brash subordinate but, when their long friendship abruptly (albeit briefly) derailed over some derogatory statements uttered in public by Davis, the plum role went to an up-and-coming young actor by the name of Steve McQueen. It was a breakout performance by McQueen, effectively leading to starring roles in shortly subsequent progression. Directed by ultimately frequent McQueen collaborator John Sturges, Never So Few is an exciting adventure film placed in the Burmese jungles as Captain Tom C. Reynolds (Sinatra) and his guerilla fighters engage in combat with the Japanese during World War Two. With lush orchestral foliage provided by composer Hugo Friedhofer, and a most decorative cast including Gina Lollobrigida, Peter Lawford (soon to join Sinatra’s exclusively jubilant pals in “The Rat Pack”), Steve McQueen, Paul Henreid, Richard Johnson, Brian Donlevy, and another up and coming young actor named George Takei, still seven years away from his own iconic performance as Mr. Sulu on NBC’s Star Trek series, Never So Few is a profoundly underrated, though thoroughly entertaining and exciting war epic.

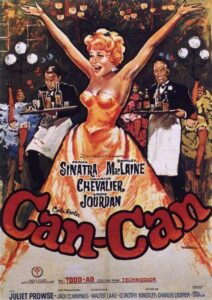

The cold war between The United States and Russia grew momentarily warmer in 1960 when Russian premier Nikita Khrushchev and his wife visited the set of Can Can at 20th Century Fox during a diplomatic trip to the U.S. The pair were invited to meet the cast of the film, as well as witness the filming of the infamous “Can Can” sequence with Shirley MacLaine and Juliet Prowse. The Russian premier, it was reported, openly enjoyed the dancing until his wife grimaced in disapproval. After that, it was business as usual between the two countries with the cold war growing ever more frigid. Can Can, directed by Walter Lang, was a big budget musical based upon the legendary stage production with music and lyrics by Cole Porter. The film is a colorful delight with wonderful comedic performances by Sinatra as a rogue Parisian attorney, Shirley MacLaine as the owner of a popular club specializing in performances of the outlawed dance, Maurice Chevalier as a lecherous judge, and Louis Jourdan as the prudish addition to the court insisting upon the letter of the law. The obvious chemistry between Sinatra and real life “pal” MacLaine is joyous, while Chevalier and Jourdan both sing and mug deliciously for the cameras. Sinatra is at the peak of his career, clearly in command of his vocal artistry, and relishing his performances of “C’est Magnifique,” “Let’s Do it” (with MacLaine) and, particularly, the exquisitely performed “It’s All Right With Me,” a nearly heart wrenching lament set characteristically in a Parisian “saloon.” It is a definitive homage to popular music’s ultimate “saloon singer.”

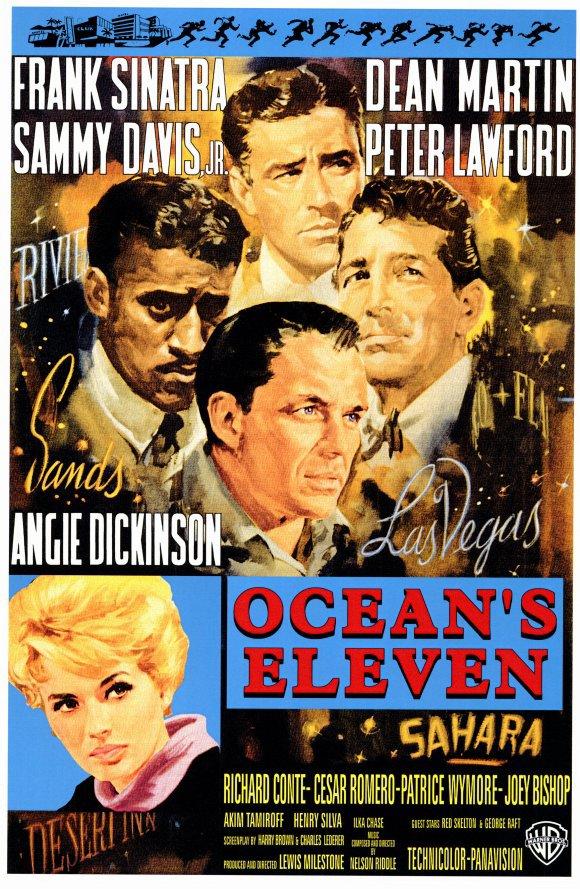

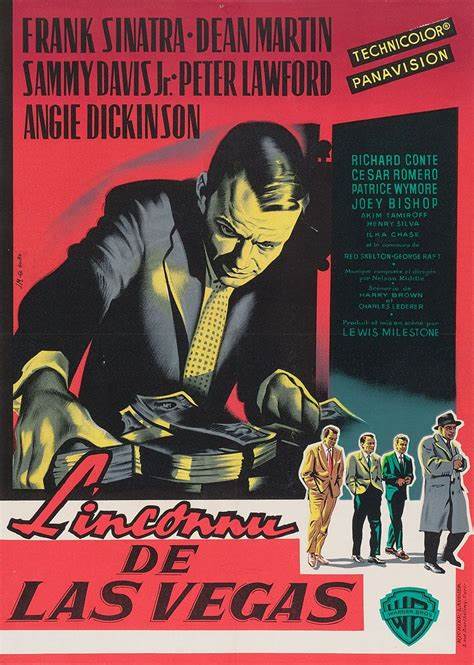

Old Sinatra pal Peter Lawford had purchased the screen rights to a hip, “buddy,” caper movie about a bunch of former soldiers conspiring to rob the Las Vegas casinos of their substantial loot. He brought it to Sinatra who then recruited many of his own buddies to co-star in the production. What seemed a simple heist adventure became one of the most iconic films of the period. Released by Warner Bros. in 1960, Ocean’s Eleven, based upon a story by co-writer, George Clayton Johnson and directed by Lewis Milestone (All Quiet On The Western Front), became significantly more than a mere motion picture. The film, its production and, in particular, its nearly all male cast, transformed the city of Las Vegas into the billion-dollar industry it has since become. While Las Vegas had offered night clubs, celebrities, alcohol, and women to high rollers for years, and had functioned prominently as a “mob” run franchise under the watchful guidance of such legendary gangsters as Bugsy Siegel, the turbulent filming of Warners’ Ocean’s Eleven changed the topography of Vegas nearly over night.

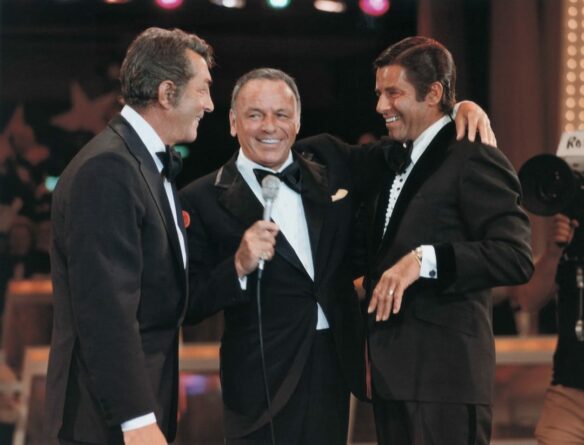

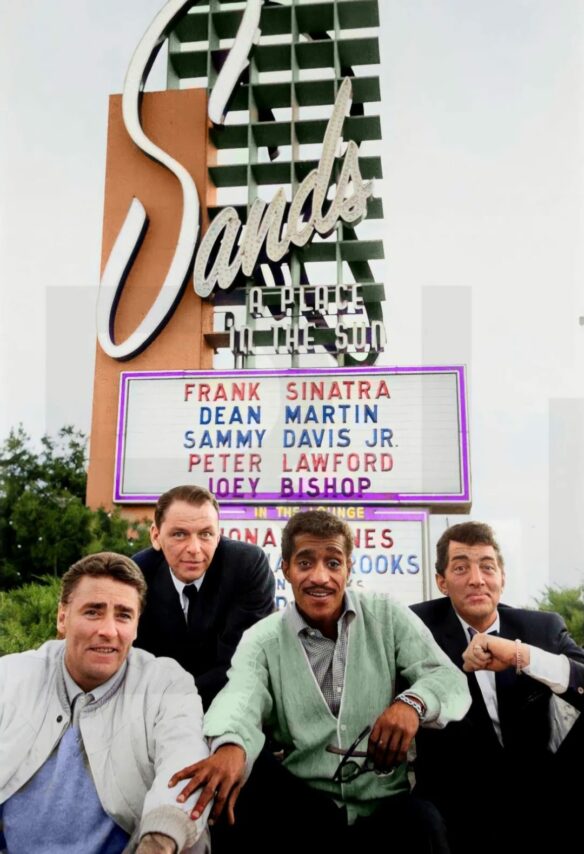

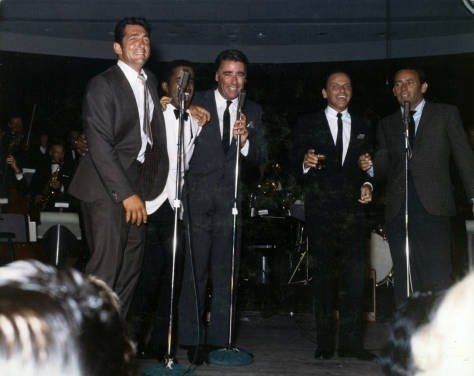

The film also gave birth to the legendary “Rat Pack,” headed by Sinatra, who gleefully invited his pals to join the laughter. While filming by day, the cast adjourned to The Sands Hotel, owned by Jack Entratter, in the evenings and often well into the night to perform, cavort, drink, and party. The nighttime attraction became as big a draw to the public as the filming of the movie. High rollers from around the globe would fight to pay exorbitant tabs just to witness Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin, Sammy Davis, Jr., Peter Lawford and Joey Bishop perform their wildly talented, anarchic musical and comedic turns on stage at The Sands at night, and into “the wee small hours of the morning.” After the death of its founding member, Humphrey Bogart, The Holmby Hills Rat Pack (of which Sinatra was a member) floundered without a rudder until Sinatra assumed command of the ritzy social group, transforming it into the hippest ensemble on the planet. The group’s legendary comradery and razor-sharp wit, performing night after night during the filming of the movie, and for countless years thereafter, by all credible accounts, virtually changed the face of the gambling city from a modest destination for gamblers to the showplace of the world. As for Ocean’s Eleven, the film itself influenced generations of celluloid caper movies, contained an uncredited voice performance by actor Richard Boone as a Las Vegas chaplain, and inspired a series of high-quality remakes starring George Clooney in the role of Danny Ocean. As overblown and expensive as these high-priced remakes were, however, they somehow never compared to the chic simplicity of the 1960 Warner Bros. original featuring Sinatra and his legendary troupe of talented bad boys, The Rat Pack.

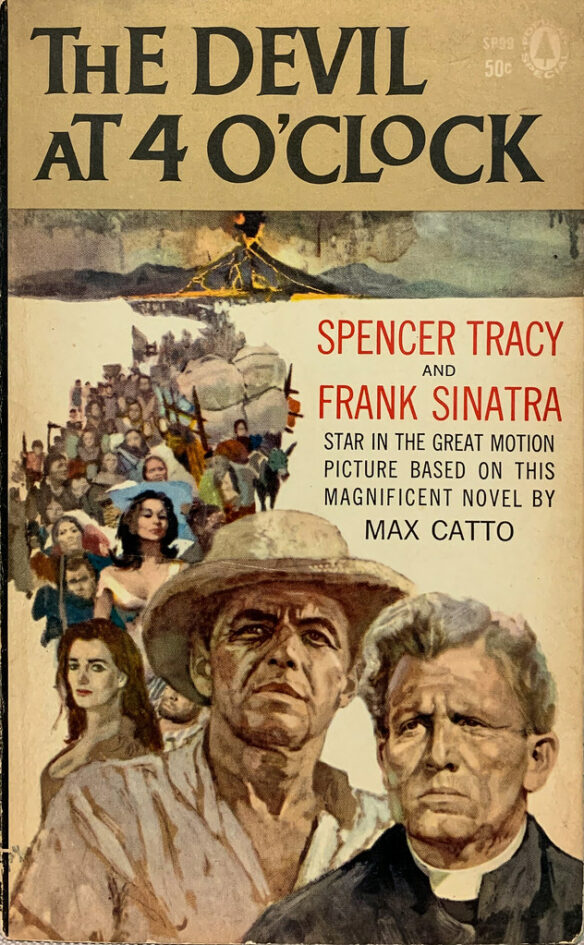

In the wake of Columbia Pictures hugely successful adventure film The Guns Of Navarone, the studio cast Sinatra with, perhaps, the greatest screen actor of both his, and any subsequent generation, Spencer Tracy, in an explosive tropical paradise on the brink of volcanic devastation. The Devil At Four O’Clock, based upon the novel by Max Catto, and directed by Mervyn LeRoy, aspired to repeat the success of the earlier production. The early poster art for the picture proclaimed that it was “in the tradition of The Guns Of Navarone, hoping that cinematic lightening might strike yet again at the box office.

While few films could survive such an unrealistic advertising comparison, The Devil At Four O’Clock is actually a vastly underrated romantic adventure filled with memorable performances, particularly by Tracy and Sinatra, as an alcoholic priest and cocky convict consigned to a lushly beautiful island soon to be consumed by volcanic ferocity. Despite some obvious indoor sets substituting for mountainous trails, the film is often exciting, powerful, and exceedingly poignant. Bernie Hamilton is a standout as a co-conspirator, struggling to break free of his shackles, while unexpectedly finding heroism in one final incomparable act of self-sacrifice, while Barbara Luna is sensually innocent and appealing as the blind girl who guides Sinatra’s own path to spiritual rebirth. The film “scores” musically, as well, with the finest work of composer George (Picnic) Duning’s long career. His original music for the picture is as profoundly haunting and beautiful as any of the film’s exotic locations. Although historically overlooked, and often ignored by self-important film “critics,” The Devil At Four O’Clock is often thrilling, singularly moving, and powerfully dramatic and poignant in its tale of irrevocable disaster and spiritual redemption.

Sinatra’s own Essex Productions was responsible for the filming of his next film. Directed by the venerable John Sturges, Sergeants 3 is a western remake of George Stevens’ 1939 RKO classic Gunga Din. Released by United Artists in 1962, Sinatra saw this somewhat updated re-telling of the Rudyard Kipling classic adventure as the ideal vehicle for his Rat Pack pals. Featuring Dean Martin in the role created earlier by Cary Grant, Peter Lawford in the Douglas Fairbanks, Jr. part, Sinatra essaying the Victor McLaglen role, and Sammy Davis, Jr. as Gunga Din, Sergeants 3 is an entertaining, comedic, irresistibly irreverent take on a beloved film. Sinatra performs most of his own, often dangerous stunt work in the picture. Out of release and distribution for some four decades, the film is largely remembered today as the second and final Rat Pack motion picture. While the later Warner Bros. production of Robin And The Seven Hoods is often erroneously looked upon as a genuine Rat Pack picture, its pairing of Sinatra, Martin, and Davis excludes both Peter Lawford and Joey Bishop. Only Ocean’s Eleven and Sergeants 3 two years later includes all five of the original Sinatra Rat Pack members in its ensemble cast.

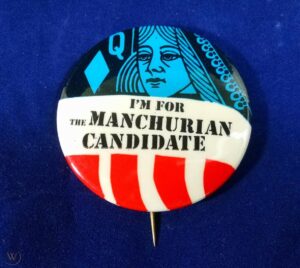

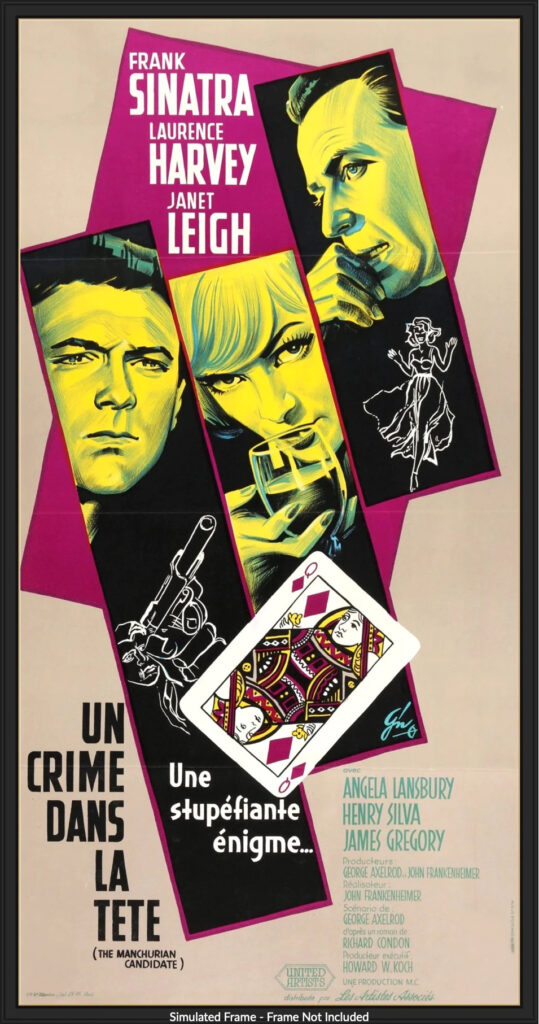

Sinatra’s next performance and film would be remembered as, perhaps, the finest work of his sizeable career. Richard Condon’s controversial political thriller The Manchurian Candidate was a favorite novel of President John F. Kennedy, and Sinatra was eager to purchase the rights to the book. United Artists was intimidated by its theme of attempted presidential assassination, and wary of financing or releasing the picture. When President Kennedy reached out to the studio, at Sinatra’s personal request, indicating that he would love to see the film produced, United Artists relented and allowed the film to be made. Released in 1962, with superlative direction by John Frankenheimer, a riveting, brilliant, and convoluted screenplay by George Axelrod, superbly valiant performances by Lawrence Harvey, Frank Sinatra, Angela Lansbury, and Janet Leigh, as well as a stunning musical score by composer David Amram, The Manchurian Candidate took the country by storm. Its shocking, often mesmerizing story of brain washing and robotic homicide during and following the Korean War, became the most fervently discussed and admired motion picture of the decade. Frankenheimer’s documentary style direction gave the film a brutally realistic look, delivering its controversial themes with ever more immediacy than might have been provided by a traditional, studio bound production.

Filmed on locations throughout New York City, the picture seems often horrifyingly real and frightening in its depiction of chemically induced paranoia and ultimate societal madness. Harvey’s performance as Raymond Shaw is the most compelling and poignant of his illustrious career, while Angela Lansbury as his morally bereft mother delivers, possibly, the most evil interpretation of motherhood ever committed to film. James Gregory is all too sadly believable as John Iselin, an intellectually bereft, reprehensible Senator based largely upon the real life proclivities of Senator Joseph McCarthy who, like the fictional John Iselin, sells his soul, as well as the reputations of numerous innocent victims of his fictitious witch hunt for communists, in order to further his own purely personal political ambitions and aspirations. After the real life assassination of President Kennedy, the film’s single greatest champion, on November 22nd, 1963, The Manchurian Candidate disappeared for decades, reportedly due to the remorse of Sinatra who felt somehow complicit in the murder of his president and friend. When the film re-emerged from exile in the early 1990s, it was both hailed and critically acclaimed as a lost masterpiece. A mediocre, ill-conceived and incoherent remake starring the otherwise gifted Denzel Washington has not diminished the reputation or reverence deservedly afforded the original production.

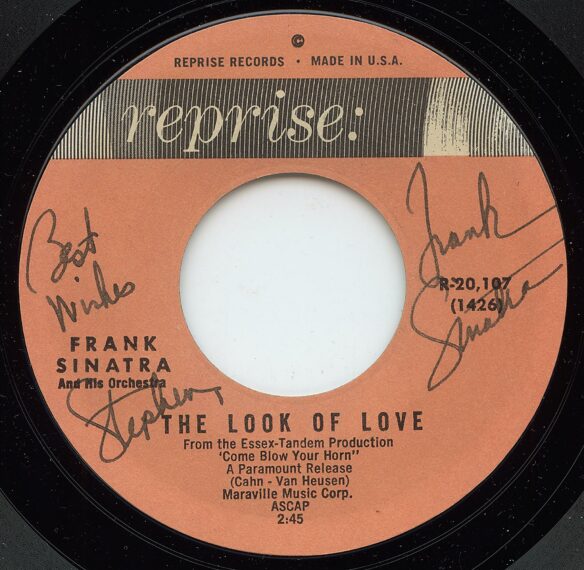

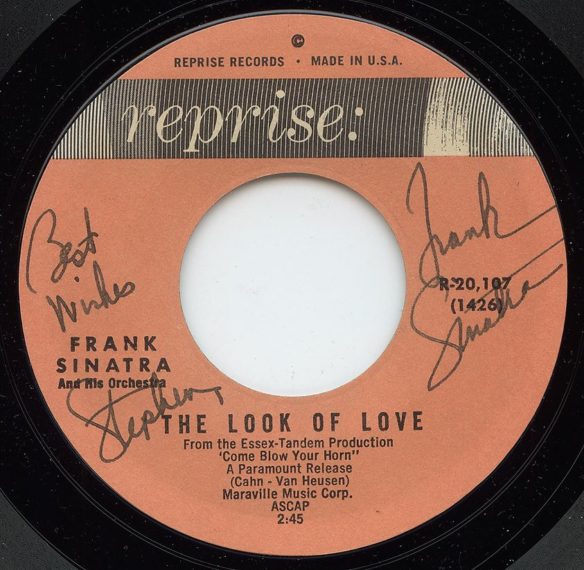

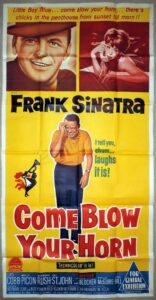

Paramount Pictures released Sinatra’s next film in 1963. Based upon Neil Simon’s first Broadway play, which premiered in 1961 in New York with Hal March in the lead, Come Blow Your Horn is a Jewish coming of age comedy in which a restless young man yearns to leave his ever suffocating, traditional ethnic nest, create his own bachelor apartment, and emulate his swinging older brother. Sinatra plays Alan Baker, the wayward roguish son of traditional, old world parents, who lives the high life while lecherously chasing after numerous models and aspiring actresses from his decadently lavish pad. His younger brother, Buddy (Tony Bill), sees only the glitzy romance of youthful bachelorhood, and decides to move in with Alan. Come Blow Your Horn, directed and scripted by Norman Lear (All In The Family), is a sparkling, often hilarious comedy gem marred in its ensuing years by changing times, revisionist interpretation, and politically correct criticisms having little or nothing to do with the trendy times in which it was first produced. The supporting cast is wonderfully befuddled with Molly Picon and Lee J. Cobb as quintessential Jewish parents charmingly out of touch with The Age of Aquarius, while Barbara Rush as Sinatra’s love interest, Connie, is radiantly beautiful in her “good girl” performance. Logic, admittedly, has been tossed out of the window here with audiences blindly accepting Sinatra as a Jewish Romeo but, with Molly Picon and Lee J. Cobb as his parents, he’d hardly be playing to his Italian heritage. Cobb and Sinatra became friends some years earlier when the older actor was stricken with a heart attack, and Sinatra paid all of his hospital bills, putting him up at his house while Cobb convalesced. Despite some dated dialogue, the film remains frequently delightful and, even by today’s moralistic standards, a joy to watch. Its musical highlight is Sinatra introducing his baby brother to the world of exclusive clothing lines while reaching astonishing high notes singing the title tune by Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen in the frenetic mean streets of New York.

Four For Texas, directed by Robert Aldrich and released by Warner Bros. in 1964 featured Sinatra with pal Dean Martin in a strictly by the numbers western with forced humor and utterly routine costume melodrama. Co-starring Charles Bronson as a gun slinging thug, along with Anita Ekberg and Ursula Andress as a mismatched pair of tough, overly masculine femme fatales, the unappealing western seems more like left over scripting than anything remotely original or inspired. The film appeared tired when it opened, and has not worn well with the passage of years.

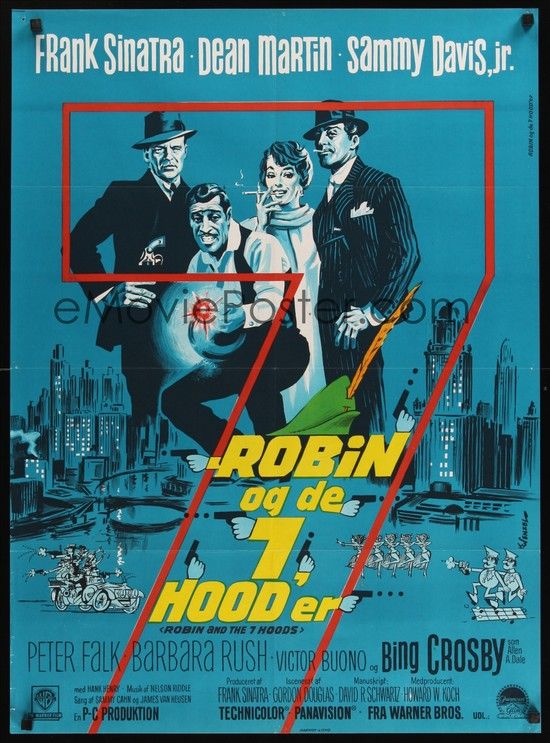

His next film for Warner Bros. would prove far more elaborate and creatively ambitious. Robin And The Seven Hoods, released in 1964, was a clever take on the legend of Robin Hood, updated to reflect Chicago’s gang wars of the 1930s. Directed by Gordon Douglas with a screenplay by David R. Schwartz, the original satire provided audiences with a big jolt of electrical star power, often amusing situations and comedic writing, bombastic performances by stars Sinatra, Dean Martin, Bing Crosby and, particularly, the enormously gifted Sammy Davis, Jr. in a delightfully over the top, quasi Jerry Lewis performance, as well as a completely new song score written for the film by the incomparable team of Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen. Peter Falk, however, very nearly steals the show as Sinatra’s hoodlum rival, Guy Gisborne. Falk mugs delightfully, and evidently delighted, for the camera in an often hilarious performance as a nefarious hood from the wrong side of the “hood.” Sammy Davis Jr. scores mightily with his wonderfully choreographed song and danced homage to his machine gun (“Bang Bang”), while Sinatra sublimely introduces what would soon become one of his most identifiable signature tunes, “My Kind Of Town,” on the steps of a bustling Chicago court house. This would be the last attempted film reunion of The Rat Pack (or “The Clan,” as it was alternately known) in that it featured three of the original five members (only the sadly disenfranchised Peter Lawford, and Joey Bishop were absent from the ensemble), and was billed essentially as a Rat Pack movie. Although Lawford and Sinatra would never speak again, due to a personal falling out over Lawford’s brother in law (President Kennedy) snubbing Sinatra’s elaborate invitation to stay at his pad, a final tragic irony would forever haunt the making of the film. It was during the funeral scene for “Big Jim” (Edward G. Robinson) that Sinatra and the cast received word that former pal, John F. Kennedy, had been assassinated in Dallas.

Warner Bros. would release Sinatra’s next film, as well. None But The Brave, released by the studio in 1965, introduced Sinatra as a first time director, as well as co-star in a subordinate role to Clint Walker, in a surprisingly thoughtful anti-war drama in which both American and Japanese soldiers find an uneasy truce while stranded on a small Pacific island during the Second World War. Based upon a story by Kikumaru Okuda, with a corresponding screenplay by John Twist and Katsuya Susaki, None But The Brave provides Sinatra with an ultimately selfless opportunity to sublimate himself in favor of Walker’s starring performance, while offering his quietly dignified direction and morality play as the true stars of the film. The final outcome of the story, though not unexpected, remains sadly haunting and poignant, and is profoundly underscored by the beautifully poetic music of composer John Williams. None But The Brave is largely forgotten today, but remains the first co-production between American and Japanese studios to be filmed in The United States, as it was lensed on Kauai Island in Hawaii. Subtle, rather than flashy…thoughtful, rather than bombastic, None But The Brave survives as a noble cinematic document portraying the madness of war.

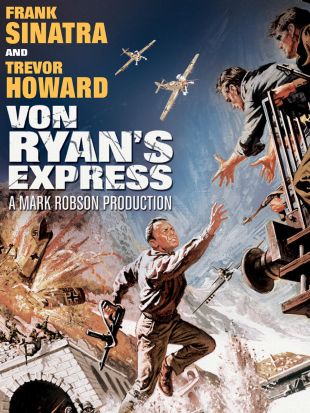

Another war film, albeit far more successful at the box office, followed the tropical solitude of None But The Brave. Released by 20th Century Fox the same year, Von Ryan’s Express would provide Frank Sinatra with another of his most memorable roles, that of Colonel Joseph L. Ryan, captured in Italy in 1943, and thrown into a crowded prisoner of war camp run by a sadistic fascist commandant. Ryan’s conciliatory exchanges with their captors earns him the name “Von Ryan,” considered a collaborator rather than a patriot, until a daring escape through German enemy lines reveals the colonel to be far more courageous than previously imagined. A thrilling train chase through the Italian Alps toward the Swiss Border provides the climactic highlight of the film. Directed by Mark Robson, with panoramic Cinemascope photography by William H. Daniels, special effects by L.B. Abbott, and a stirring musical score by composer Jerry Goldsmith, Von Ryan’s Express would provide Sinatra with one of his most charismatic performances, as well as one of his biggest hits. His death scene, occurring ironically just when victory appears certain, while Nazi soldiers desperately attempt to prevent a final escape, is as memorable and poignant a finale as any in film history.

Physically exhausted upon the completion of Von Ryan’s Express in Italy, Sinatra’s next project appears equally tired, an awkward attempt to catch his creative breath. Marriage On The Rocks, released by Warner Bros. in 1965, is an utterly humorless comedy with simplistically bland “sit com” aspirations that never rises beyond its dreary plot devices. Utterly predictable, and predictably boring, this unimaginative look at a crumbling marriage features Sinatra, unbelievably cast as a lifeless spouse whose wife, played by Deborah Kerr, looks for greener pastures and a more exciting mate. Pal Dean Martin plays his playboy bachelor friend who tries to teach Sinatra how to be a swinger. Directed by Jack Donohue, Marriage On The Rocks lectures and preaches with a sledge hammer, and is among the most forgettable of Sinatra’s screen appearances. Not even a “laugh track” would have saved this laughably inarticulate attempt at farce.

Sinatra fared far better, and somewhat more credibly, in his next starring venture for Paramount Pictures. Relatively comfortable and at home in another caper film, the singer and pals conspire to “stick up” The Queen Mary while at sea in Assault On A Queen, released by the studio in 1966. Lacking the charm, humor, clever scripting and sophistication of his earlier Ocean’s Eleven, this Jack Donohue directed thriller was infinitely more user friendly and comfortable for Sinatra than his earlier, Donohue helmed “romantic comedy.” Based upon a novel by writer Jack Finney (“The Body Snatchers”) and a screenplay by Rod Serling (“The Twilight Zone”), Assault On A Queen is a reasonably well defined heist flick that offers a degree of suspense, along with attractive performances from Sinatra, Virni Lisi and, particularly, Tony Franciosa as an overly greedy provocateur whose nervous unprofessionalism ultimately sabotages the not so well oiled machinery. Duke Ellington’s edgy jazz score gives the picture a quirky lift, adding to the necessary tension of the story. While not a great or memorable film, Assault On A Queen is, nonetheless, a pleasant escapist diversion.

The Naked Runner, released by Warner Bros. in 1967, is a ponderous, slow moving spy thriller filmed in Europe, featuring a largely European cast that somehow feels out of kilter with Sinatra’s decidedly American persona. Unimaginatively directed by Sidney J. Furie, The Naked Runner never seems to come to life or find a voice of its own. Sinatra plays Sam Laker, an American businessman residing in London with his fourteen-year-old son. A wartime marksman, Laker is contacted by British Intelligence, and asked to assassinate a double agent who has defected to the communists. When Laker refuses the assignment, his little boy is kidnapped and held for ransom until the killing has been accomplished. Sinatra appears uncomfortable both in the role, and in his surroundings, while Furie’s uninspired direction and an often lethargic cast of performers do little to enhance the dullness of an ultimately shabby, unpleasant story. As a cold war thriller, the picture fails miserably and has all but been forgotten, lost in the shadow of far more memorable thrillers such as The Spy Who Came In From The Cold. Perhaps the single memorable element to emerge from this turgid melodrama was its theme song, “You Are There” with music and lyrics by Harry Sukman and Paul Francis Webster, which Sinatra recorded with modest success at the time of the picture’s release.

20th Century Fox released the first of two relatively popular Sinatra hits in 1967. Tony Rome began a brief new franchise about a hip Miami private detective whose arsenal of accoutrements included his own boat (“The Straight Pass”), a ready supply of booze, and an even readier supply of women. Hard-bitten, cynical, and world weary, Rome is a classic private investigator in the mold of Humphrey Bogart, and authors Raymond Chandler, and Dashiell Hammett. As directed by Gordon Douglas, he is a gritty no-nonsense sleuth delving into the sleazier sides of the Miami strip. Joined by old pal Richard Conte as local cop, Lieutenant Santini, Sinatra is very much in his element as a swinging private eye aided and abetted by bikini draped women (Jill St. John), rich, pouting young girls (Sue Lyon), and a predatory stepmother (Gena Rowlands). Punctuated by Lee Hazlewood’s sultry title tune, provocatively sung by daughter Nancy Sinatra for the soundtrack, Tony Rome is a solid, if cliché ridden, look at the often sordid world of private eyes and their similarly assorted, well oiled “dames.”

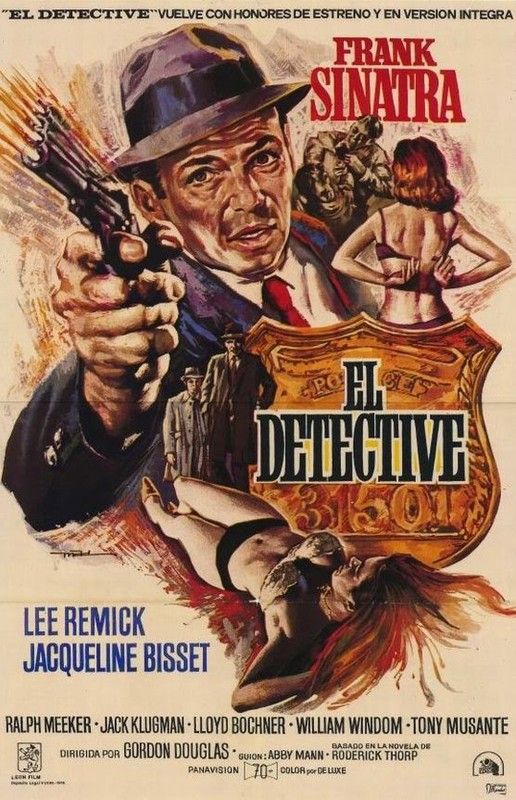

The following year would welcome the release of, perhaps, the final major film of Sinatra’s career. Directed once more by Gordon Douglas, released by 20th Century Fox in 1968, and based upon the bestselling novel by Roderick Thorp, The Detective concerns a career minded police officer investigating the brutal murder and gruesomely sensational, sexual mutilation of a prominent gay man. Sinatra’s Joe Leland is an intensely honest police detective whose crime solving skills have made him the best homicide cop on the force. Desirous of promotion, Leland is pressured by his superiors and by City Hall to crack the case quickly or see his promotion given to another. When Felix Tesla (Tony Musante) is suspected of the killing and subsequently arrested, Leland uncomfortably coerces a confession out of the obviously disturbed felon, thereby sending him to the electric chair for the crime. Joe then receives his needed acclaim for cracking the case so quickly. When the apparent suicide of a respected businessman, Colin MacIver (William Windom), occurs sometime later, his widow, Norma (Jacqueline Bisset), comes to Leland with the proposition that her husband could not have taken his own life, and that his death was enabled by politically motivated circumstances more sinister and entrenched than initially imagined. Leland’s life is further complicated by an alcoholic, nymphomaniac wife (Lee Remick), and the possibility that his psychologically manipulated confession from Tesla was responsible for electrocuting the wrong man. With an outstanding supporting cast of players, including Remick, Bisset, Windom, Ralph Meeker, Horace McMahon, Lloyd Bochner, Jack Klugman, and Robert Duvall, The Detective benefits from a strong, mature performance by Sinatra as the veteran police detective conflicted by his personal integrity and honor, and by the departmental pressure to score just one last big arrest in order to insure his future and security on the force. Accompanied by composer Jerry Goldsmith’s haunting, melancholy jazz score, The Detective provided a significant box office hit for both Sinatra and his studio. Mia Farrow, then the third Mrs. Sinatra, had been set to play the part of Norma MacIver in the film, alongside her husband, but when the high-powered couple separated after Farrow’s insistence on starring in Roman Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby for Paramount, the relatively unknown Jacqueline Bisset was signed for the coveted role.

Following on the heels of Joe Leland, Sinatra decided to hang out his investigator for hire sign once again, starring in the glossy sequel to Tony Rome. Lady In Cement, directed once again for 20th Century Fox by Gordon Douglas, essentially completed the “detective” trilogy, pairing the actor and director for the third consecutive time in two short years. More entertaining, perhaps, than its gritty, deadly serious predecessor, the second and final film in the brief Tony Rome series finds the flip gumshoe discovering the nude, dead body of a shapely young blonde adorning the bottom of the local waters where he has been scuba diving. Her feet encased in a thick block of cement, thereby “sealing” her fate, the young woman’s murder sets Tony off on his latest case and, in the process, encountering a bikini draped Raquel Welch as his soon to be love interest, along with Richard Conte as Lieutenant Santini, and an overly imposing ex-con named Earl Gronsky (Dan Blocker) who, like Moose Malloy in the earlier Murder My Sweet, hires Rome to find out who murdered his own reincarnated version of “Velma.” Though innocuous, Lady In Cement remains a joyful guilty pleasure.

Dirty Dingus Magee, released by MGM in 1970 will ever stand as the worst career decision of Frank Sinatra’s otherwise brilliant film career. With a screenplay inexplicably crafted by, among others, Joseph Heller (Catch-22), and directed by Burt Kennedy, this atrociously unfunny western “comedy” unimaginably stars Sinatra as a hopelessly simple minded “boob,” an incompetent crook whose artless thievery places his uninspired freedom in jeopardy. Sinatra, the virtual epitome of style, class, and sophistication, is cast as a half-witted hick whose unappealing stupidity keeps him barely one step ahead of the law, and in the beds of equally simple minded whores and witless young ladies of questionable intelligence. This utterly tasteless, supposed “spoof” stands as a horrid testament to one of the most heinously wrong casting decisions in film history, and to a film whose original “negative” elements are hopefully corrupting more aggressively than the corroded production decisions that sired its production in the first place.

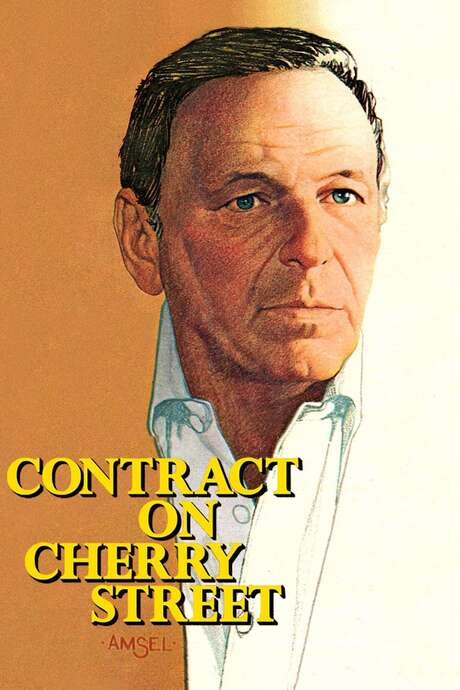

Stung, perhaps, by critical derision and mediocre box office receipts for Dirty Dingus Magee, Sinatra would not return to the screen for seven years and, when he did, it would be for a medium that he had more control over…television. Contract On Cherry Street was one of the most highly promoted and anticipated events of the late 1977 tv season. Produced for NBC Television, the motion picture aired over two nights, beginning on November 19th, 1977. Directed for television by William S. Graham, with a teleplay by critically acclaimed screen writer Edward Anhalt, and original music by Jerry Goldsmith, Contract On Cherry Street was vintage Sinatra. Produced by Sinatra’s own production company, Artanis (Sinatra spelled backward, and the name he used when painting), the actor played Frank Hovannes, a tough New York cop battling the mob and local thugs whose eventual undoing is unwittingly determined by one of his own men, a rogue cop bent on his own brand of street vigilantism. Co-starring Martin Balsam, Harry Guardino, and Martin Gabel, Contract On Cherry Street knocked it out of the park for Sinatra. His performance as a scarred veteran of the police force was tough, unflinchingly honest, and utterly mesmerizing. The book by Phillip Rosenberg, upon which the mini-series was based, was said to be a favorite of the actor’s late mother, and so he took pains to deliver a carefully textured and gritty performance. Location shooting on the streets of New York and New Jersey added a sense of urgency and realism to this often compelling and exciting movie for the deceptively “small” screen upon which it premiered.

Three years later, Sinatra returned to theatrical screens for one more outing. The First Deadly Sin (Filmways,1980), directed by Brian G. Hutton, was a slow, depressing tale of a police officer struggling with a series of grizzly unsolved murders, while caring for his cancer-ridden wife, hospitalized without hope of survival. The film had originally been intended as a vehicle for director Roman Polanski but, when Polanski fled the country after accusations of raping an underaged young girl, the directing chores were regretfully re-assigned. Had Polanski remained and directed the film, the end results might, perhaps, have been more interesting. With a fine, mature cast that included Fay Dunaway as Edward Delaney’s (Sinatra) wife, James Whitmore, Martin Gabel in his final performance, and a walk on by an uncredited young actor named Bruce Willis, The First Deadly Sin contains deeply melancholy performances by both Sinatra and Dunaway that caress one’s heart strings. The film, however, fails to ignite its pivotal story, ultimately degenerating into successively brooding, dark interludes that leave its target audience deflated and depressed. Sinatra is particularly touching in his portrayal of a weary soul watching his minimal world crumbling before him. Sadly, the film failed to reach an audience and passed mercifully into memory.

While it initially appeared that his role as a grieving cop would become his last screen performance, a seemingly improbable invitation would lead, some seven years later, to Sinatra’s actual dramatic swan song. Tom Selleck was an enormous admirer of the legendary performer and Sinatra, in turn, was an admitted fan of Selleck’s hit CBS television series, Magnum P.I. Sinatra openly declared that if the producers of the series ever found a suitable role for him, he’d seriously consider acting on the series. On February 25th, 1987, an episode of Magnum entitled “Laura” debuted on the network. A tough New York police officer has announced his retirement from the department. On the night of his retirement dinner, an innocent little girl in a large apartment building is raped and murdered by a savage, predatory pedophile. Michael Doheny (Sinatra), now retired but working as a private investigator, is haunted by the case and actively devoting his time to pursuing a suspect now living in Hawaii. His abrasive methods run afoul of Magnum, causing conflict in an uneasy relationship between the two investigators, until the alleged murderer is finally confronted and accidentally killed in a fall off of a roof, and it is ultimately revealed that Doheny…was the child’s loving grandfather. Sinatra’s performance is quite touching, while his grieving over the loss of his beloved granddaughter is genuinely poignant, and heartbreakingly moving. After garnering positive critical and audience approval, there was some discussion of the actor returning to the series for yet another episode during the following season. Time and availability would eventually erase the possibility of a return to the series, however, but…for one brief shining moment in the sun…Frank Sinatra had once more touched the stars, and risen beyond the clouds to create magic yet again…for one enduring, final moment.