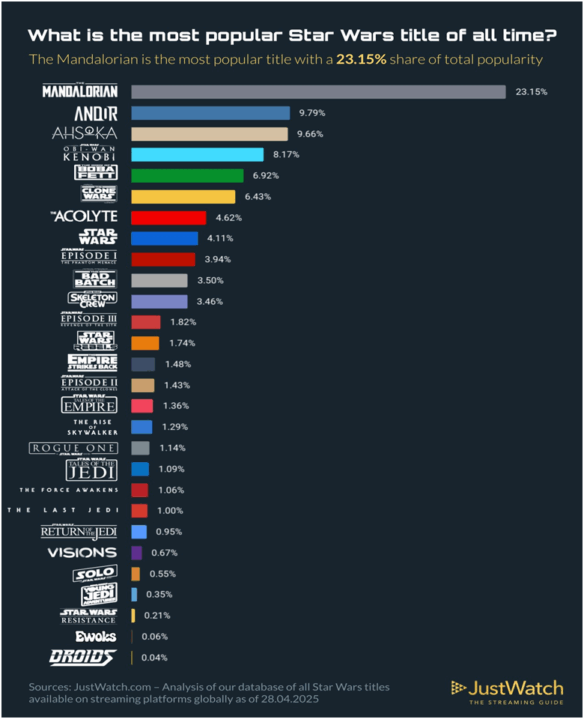

(1) JUSTWATCH REVEALS THE MOST-STREAMED STAR WARS TITLES. JustWatch, the world’s leading streaming guide, released an exclusive report ahead of Star Wars Day (May the 4th), diving into the most-streamed titles across the Star Wars universe.

From the timeless legacy of George Lucas’ original trilogy to the power of Disney’s modern revival, JustWatch’s findings reveal how the Force continues to captivate American audiences.

Drawing from millions of data points collected from JustWatch users, the report uncovers the top-performing Star Wars films and series and how streaming preferences vary between generations of fans.

Key Findings

- “The Mandalorian” Reigns Supreme: Disney+’s flagship series outperformed the original trilogy by over 25%, cementing its status as the most-watched Star Wars title.

- Film Favorites Still Fly High: Episode V: The Empire Strikes Back remains the most-streamed film from the Lucas-era classics, while The Rise of Skywalker leads among Disney’s theatrical releases.

- Old vs. New: Though newer series like Ahsoka and Andor surged in popularity in 2024, the original trilogy collectively still held over 30% of the film streaming share.

- Anakin Showdown: Hayden Christensen’s portrayal in the prequels has seen a resurgence, outpacing Jake Lloyd and even early Mark Hamill-led films in younger demographics.

- Hidden Gems: Despite critical acclaim, Star Wars: Visions and The Book of Boba Fett landed among the least-streamed titles.

Methodology: Streaming interest is based on JustWatch user activity globally, from 2019-April 28th, 2025, including interactions such as adding titles to watchlists, click-outs to streaming platforms, and filtering by service providers. JustWatch aggregates data from over 60 million monthly users across 140 countries.

(2) EFFECTIVENESS OF STATE PRODUCTION INCENTIVES. The New York Times asks, “When Taxpayers Fund Shows Like ‘Blue Bloods’ and ‘S.N.L.,’ Does It Pay Off?” (Behind a paywall.)

New Yorkers — and residents of many other states — have paid more for entertainment in recent years than just their Netflix or Hulu subscriptions.

Each New York household has also contributed about $16 in taxes, on average, toward producing the drama series “Billions” since 2017. Over that period, each household has also paid roughly $14.50 in production incentives for “Saturday Night Live” and $4.60 for “The Irishman,” among many other shows and movies.

Add it all up, and New York has spent more than $5.5 billion in incentives since 2017, the earliest year for which data is readily available. Now, as a new state budget agreement nears, Gov. Kathy Hochul has said she wants to add $100 million in credits for independent productions that would bring total film subsidies to $800 million a year, almost double the amount from 2022.

Other states also pay out tens or hundreds of millions each year in a bidding war for Hollywood productions, under the theory that these tax credits spur the economy. One question for voters and lawmakers is whether a state recoups more than its investment in these movies and shows — or gets back only pennies on the dollar….

… A recent study commissioned by Empire State Development, the agency that administers the tax credit, found that for every dollar handed out, about $1.70 was returned via local or state taxes, meaning the program was profitable for the state.

But many economists say these programs are money losers. A separate study commissioned by the New York State Department of Taxation and Finance estimated a return of only 31 cents on the dollar….

…A recent survey of incentive programs by The New York Times estimated that states had paid out more than $25 billion over 20 years. Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom of California cited the size of New York’s subsidies when he proposed increasing his state’s tax credits to $750 million from $330 million….

(3) THUNDERBOLTS* CHOICE QUESTIONED. [Item by Steven French.] The Guardian’s Ben Child frets about introducing Sentry into the Marvelverse in the latest “Week in Geek” column: “Has Marvel shot itself in the foot by bringing superfreak Sentry into Thunderbolts*?”

Is there ever a right time to introduce into your superhero universe a psychologically unstable god-being with the potential to sneeze a continent off the map? It is probably not when – 17 years in – you are being accused of having lost half your audience to superhero fatigue. But that’s exactly what Marvel is doing this weekend as Thunderbolts* brings us Sentry, quite possibly the freakiest superhero to ever grace the comic book publisher’s hallowed pages. You thought Rocket Raccoon was weird and unhinged? Reckon Moon Knight is a bit of a handful? This guy makes them look like well-adjusted professionals with decent pensions.

(4) THE HANDMAID’S TALE Q&A. Leading into the show’s final season, in “‘The Handmaid’s Tale’ Wants to End With a Message of Hope” the New York Times hears from actors Yvonne Strahovski and Elizabeth Moss (who is also a producer and director on the series); Bruce Miller, the creator; Warren Littlefield, a producer; and Yahlin Chang and Eric Tuchman, the Season 6 showrunners. (Behind a paywall.)

…When you originally conceived of this show, how faithful to Margaret Atwood’s novel did you feel like you had to be?

BRUCE MILLER I first read “The Handmaid’s Tale” in college. I’m dyslexic, so I tend to read the same books over and over. Since it became one of my favorites, I didn’t want to mess it up in an adaptation. The key, for me, was not fealty to the book or Margaret as an artist — it was born out of the storytelling in the novel that had already stood up to a whole bunch of readings. There are parts in it that I have never understood.

ELISABETH MOSS Margaret’s tone is so specific to her voice and writing that it was really important for that to be part of the show. As a producer, if I’m sent something and someone says, “I don’t see how you make this into a film or a show.” I’m like, “Have you read ‘The Handmaid’s Tale’?” It’s a first-person narrative that follows one person’s perspective the entire way, has a ton of loose ends and ends abruptly with no explanation.

Like the book, the show often feels politically prophetic, but it is much more racially and culturally diverse. What were some of your priorities when it came to adapting the novel?

MILLER: I decided at the beginning that fertility would trump everything. That once the fertility rate went down by 95 percent, people’s racism, sexism and whatever-ism would slide. I was completely wrong, based on what happened in the last 10 years. That stuff is more intractable than I ever thought it was. But on a much more practical level, it didn’t make sense for me to, by following the book, keep a whole bunch of actors of color from working.

WARREN LITTLEFIELD We wanted it to be relevant. But if we’re going to resonate, then why not reflect the world we live in?

The show was developed during the Obama years and even then, we could see the radical right rising throughout the world and in the United States. Did we think that was going to settle into the White House? We didn’t. But when we were about to shoot Episode 4, we realized that No. 45 was going to be Donald J. [Trump], so we found ourselves doing this show at that time. Months later, Hulu purchased an ad spot for the show during the Super Bowl, it played twice, and then suddenly we were claimed as part of the resistance….

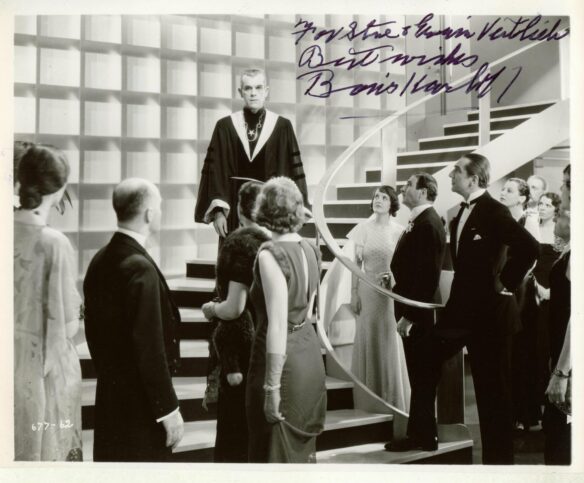

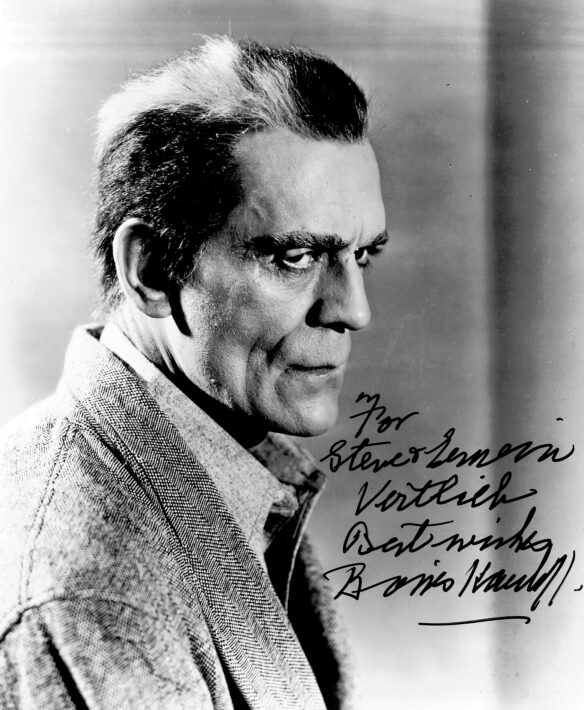

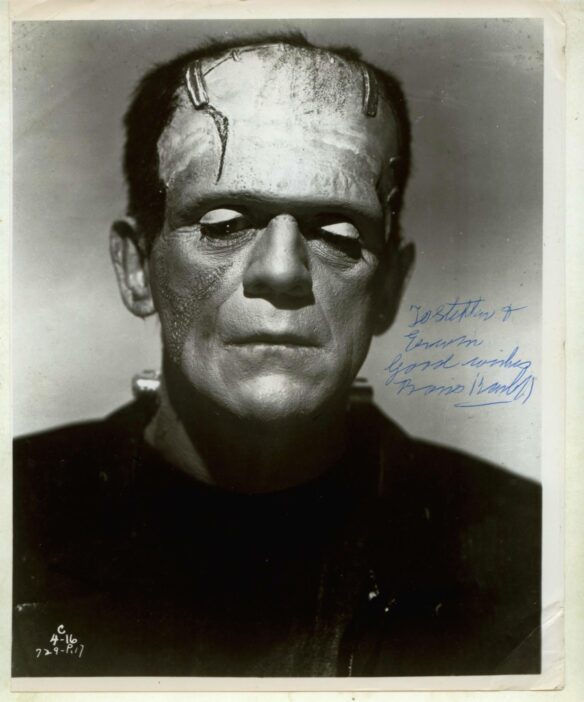

(5) THE FACE (BOOK) ON THE CUTTING ROOM FLOOR. Steve Verlieb celebrates his release from Facebook jail.

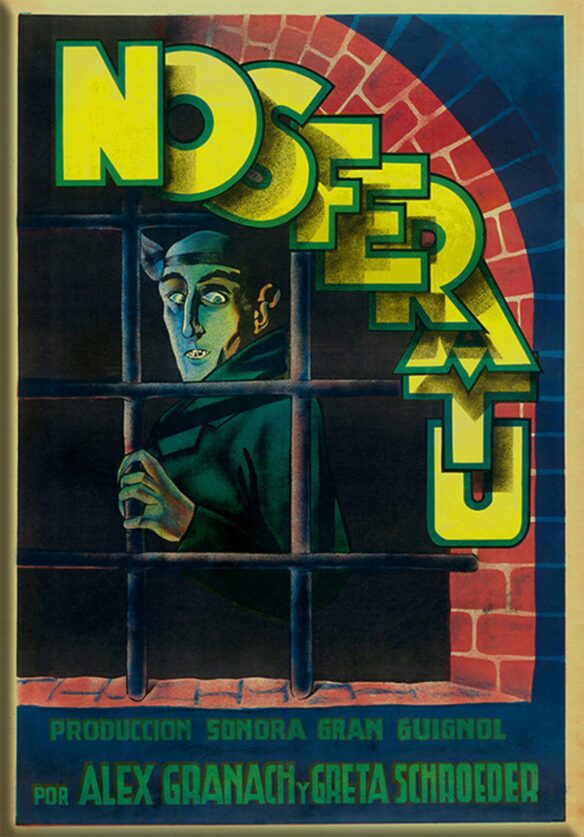

One or ten of you may have noticed that I’ve been “Missing in Action” (M.I.A.) from Facebook for a fairly substantial amount of time. Whether M.I.A., MS13, OR MSNBC, the fact of the matter is that I’ve been rotting away in Facebook prison without the benefit of legal defense for some time. While incarcerated, I wasn’t even Afforded a Harrison or “Cell” phone with which to notify friends and family of my precarious circumstances. My “crimes” included the audacity and utter indignity of sharing my own articles with others of like-minded affiliation and persuasion. In the depths of my despair, I wasn’t even permitted to drown my virtual sorrow in the local prison “bars.” I was surreptitiously removed from active recognition and participation on Unsocial Media by I.C.E. without the lawful declaration of my Lin-Manuel “Miranda” rights.

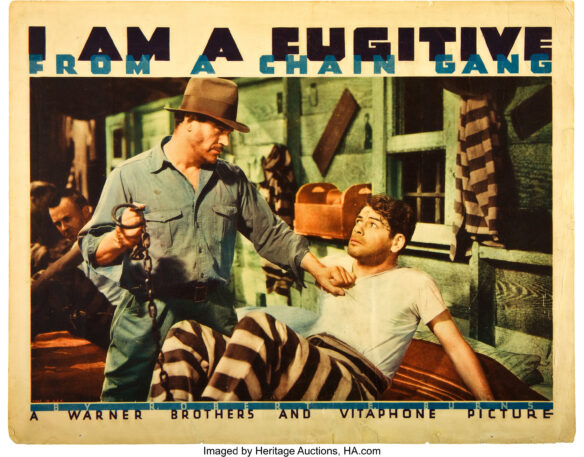

My eventual “sentence,” while not quite as long as a “paragraph,” was nonetheless both shameful and humiliating. Denied the privilege of legal counsel, with not an active “Mason” in the “Big House,” not even Raymond Burr (or even Aaron Burr) could help me “Escape from Alcatraz.” Despite the presence of some illustrious prison mates, like Charlie “Byrd,” man, with no strings attached, this proverbial “Jailhouse” did not “Rock.” Not even my continuing letters and messages to friends and neighbors offered any semblance of appeal or hope of freedom, and so I fled into a “Long Day’s Journey into Night,” while desperately hiding the disgrace that “I Am a Fugitive from a Chain Gang.”

With an increasingly inflationary Writ for what I Wrote upon my head, the gavel ultimately sent me to the gravel under the cruel reign of Warden Zuckerberg. It seemed that I’d become a permanent resident of “The Big House” when suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, I was delivered a perhaps tentative reprieve, and allowed access to the burning blaze of freedom once more. Free At Last, Free At Last, I was a “Stranger in a Strange Land,” having to re-learn the “dues” and don’ts, as well as the ins and outs, of safe navigation across the inflamed countryside of social media. However, I must be up Front in my declaration of joy in being Back once more, and I sincerely hope that you’ll both forgive, and pardon my pardon … with “Biberty” and James Robertson Justice for All.

(6) JACK KATZ (1927-2025) In “Jack Katz, 1927-2025”, The Comics Journal profiles the late creator’s complete 60-plus-year career.

Artist/writer Jack Katz, whose ambitious indy epic, The First Kingdom, laid the groundwork in the 1970s for long-form graphic narratives like Cerebus, died April 24 at the age of 97. If he had not published that science-fantasy saga, it’s likely that Katz would have been regarded as just a journeyman artist, who tried — with little success — to make a living in comics. As it is, he will be remembered for his attempt, during the waning days of underground comics, to put out one of the first self-published graphic novels….

… After he moved to California, Katz encountered underground comics and realized that self-publishing would give him the freedom to craft his own stories and art without anyone dictating to him the direction and scope of his story or the pace at which he had to work, which was always an issue with the slow and meticulous Katz.

He began putting out The First Kingdom in 1974, published by Comics & Comix Co., which remained his publisher until 1977 (issues #1–6). Longtime book-dealer and fanzine-publisher Bud Plant took over publishing from 1977 until 1986, re-offering #2-6 and completing Katz’ first story cycle of 24 issues. Always a deliberate and diligent worker, Katz only put out two issues a year and wrote and drew every comic, never working with assistants. No one had ever done an independent comic book quite like The First Kingdom, and Katz’s efforts were praised in the pages of both Playboy magazine and the Rocket’s Blast Comicollector fanzine. Although the series had its fervent adherents, Katz’ fan base was never very large, because his comic book never had newsstand distribution and was only available by mail order, in comics shops or in head shops alongside underground comics like Zap Comics, Slow Death and The Fabulous Furry Freak Brothers. Its commercial appeal was also limited by the infrequency with which the title appeared and by its adult content, which restricted its venues.

The First Kingdom storyline was a fantasy/science-fiction hybrid, with a growing emphasis on the science fiction component by the sixth issue. It began in a primitive, post-nuclear world populated by barbaric peoples, anthropomorphic gods and strange monsters….

(7) TODAY’S BIRTHDAY.

[Written by Cat Eldridge.]

May 4, 1976 — Gail Carriger, 49.

Steampunk and mannerpunk, it’s time to talk about both, specifically that as written by our birthday author, Gail Carriger.

Where to start? Her first novel, Soulless, is set in an alternate version of Victorian era Britain where werewolves and vampires are members of proper society. Alexia Tarabotti is a wonderful created character that anyone would love to have an adventure with, as well as sit down with to high tea in the afternoon.

The book begins the Parasol Protectorate series centered around her, which as of now goes on to have Changeless, Blameless, oh guess, Heartless and Timeless in it, plus one short story, “Meat Cute”. Why the latter broke the naming convention I know not.

Wait, wait, don’t tell me! — she’s done more mannerpunk. Indeed she has. There is Custard Protocol series (Prudence Imprudence, Competence and Reticence), also set in Parasol Protectorate universe. When Prudence “Rue” Alessandra Maccon Akeldama , a young woman with metahuman abilities, is left an unexpected dirigible in a will , she does what any sensible (ha!) alternative Victorian Era female would do — she names it the Spotted Custard and floats off to India. Need I say adventures of a most unusual kind follow? I really love this series and not just for the name of the series. It’s just fun. Really fun.

The Finishing School series is set in Parasol Protectorate universe. Again she has a delightful manner in naming her tales, Etiquette & Espionage, Curtsies & Conspiracies, Waistcoats & Weaponry and Manners & Mutiny. Go ahead, I think you can figure what this series is about without me telling you. It’s delightful of course.

So I’m not that familiar with her other writing. It appears the two Delightfully Deadly novellas might have a tinge of romance in them though at least one also has dead husbands, four to be precise, lobsters and of course high society. Lobsters?

The Claw & Courtship novellas are standalone stories set in the Parasol Protectorate universe. So far there’s just “How to Marry a Werewolf (In 10 Easy Steps)”, though she says there’ll be more.

Finally, I’ll note she did a SF series, the Tinkered Stars Universe series — how can this possibly be? — which she describes on her website as “a sexy alien police procedural on a space station”. Oh, that sounds so good. It consists of Divinity 36, Demigod 22, Dome 6, Crudat and The 5th Gender.

Did she do short stories? Just six, of which I really want to read one — “The Curious Case of the Werewolf that Wasn’t, The Mummy that Was and the Cat in the Jar”.

(8) COMICS SECTION.

- Off the Mark has lightsaber trouble.

- Bob the Squirrel tries the Force.

- Foxtrot runs into a nonbeliever.

- Rhymes with Orange meets another X-wing pilot.

- Brevity markets to special customers.

- Brewster Rockit introduces the challenges of a new planet.

- Brilliant Mind of Edison Lee has a game that cannot be played for money.

- Broom Hilda knows the difference between first novel and second.

- Herman knows why there are no more Martians.

- Reality Check turns apps into characters.

(9) THE SYNDICATE’S TAKIN’ OVER. Rick Marschall starts a series on newspaper syndication in “Yesterday’s Papers: An Inside Look Into The Bullpen Of Early Hearst Cartoonists”.

…The competition, particularly among their comics and cartoons, between Hearst and his rivals, had become so intense that some services had a surfeit of talent. By 1917 his comics operation filled the daily and Sunday pages of the dozen papers in the Hearst chain. A few years earlier the Hearst organization had spun off Buster Brown, Little Nemo, Polly and Her Pals, and other strips under a purportedly rival umbrella, the Newspaper Feature Service. This enabled Hearst papers to run two comic sections every weekend, perhaps one on Saturday, or to provide Hearst rivals in certain cities with their own comic sections that didn’t appear to be generated by Hearst! (In New York City, for instance, Hearst’s deadly competitor the New York Tribune was able to run a four-page NFS color comic section that appeared to readers to be the Trib‘s own.)

By 1917, Hearst’s lieutenant Moses Koenigsberg split up the syndicate operations even further. Eventually there was King Features, a sort of holding company or sales agent for all the syndicates; Central Press Association; International Feature Service, Newspaper Feature Service; and others. The material we will be sharing here and over subsequent weeks is from a rare book published for prospective clients by the International Feature Service….

(10) TRIVIAL TRIVIA. Alvin!!!

(11) MURDERBOT SHOWRUNNERS Q&A. The Grue Rume Show interviews film makers Chris Weitz and Paul Weitz. They write and direct Season 1 of Apple TV show MurderBot. “Chris Weitz and Paul Weitz talks Murderbot!!”

(12) ALEXANDER SKARSGÅRD’S SWEDISH MOMENTS. The Swedish actor’s occasional use of his native language in otherwise English-language productions is celebrated in this interview conducted by Jonatan Blomberg from Moviezine: “Murderbot, Lady Gaga & True Blood”.

I had a truly awesome time with Alexander Skarsgård, one of our best Swedish actors right now! We spoke about the times he’s been bringing our Swedish language in to American productions – which is also the case (in one brief moment) in his new show Murderbot. Here he tries to remember the “krokodil” when skinny-dipping in True Blood and sharing a bed while chatting in Swedish with LADY GAGA in the Paparazzi music video.

(13) HOW THE LEAD CHOSE THIS ROLE. And if you haven’t had enough, Winter Is Coming also scored a few minutes with the lead: “Alexander Skarsgård: Murderbot EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW!”

Winter Is Coming’s Daniel Roman sits down with Murderbot star Alexander Skarsgård to talk about becoming the SecUnit at the heart of Apple’s new comedic sci-fi series, how he embodied the character, and guilty TV pleasures.

(14) THEY DON’T LISTEN TO GURATHIN. This interview with the actor who plays Gurathin has much deeper insights into the series, plus clips: “David Dastmalchian talks ‘Murderbot’ and more: A blockbuster year for the versatile star” at Pix11 News.

[Thanks to Chris Barkley, Cat Eldridge, SF Concatenation’s Jonathan Cowie, Mark Roth-Whitworth, Steven French, Kathy Sullivan, Teddy Harvia, Mike Kennedy, Andrew Porter, and John King Tarpinian for some of these stories. Title credit belongs to File 770 contributing editor of the day Kip W.]