Harry Harrison passed away August 15 at the age of 87. Born and raised in the U.S., he lived in several other countries, including Ireland for many years, before dying in England. The SFWA Grand Master (2009), inductee of the SF Hall of Fame (2004), and past Worldcon guest of honor (1990) was also co-founder of World SF and part of the famed Hydra Club.

After I discovered sf in the 1960s and set about reading everything in the library, I became a fan of Harrison’s fiction both in its own right and as a dialog with his contemporary writers. While that was unmistakable in outright satires like Bill, The Galactic Hero, a send-up of Heinlein, Dickson and Asimov, it was also true of his straight fiction, like Deathworld (a 1961 Hugo nominee serialized in Astounding) or his series of matter-transmitter stories.

I soon learned through fanzines that most sf writers feel they are part of a literary conversation, however, fanzines also allowed me to witness the combative side of Harrison’s personality, the need to define himself by opposition to perceived wrongdoing, even if it might be hard for anybody else to see the difference. For example, readers found plenty of action in novels like Deathworld, but Harrison saw his violence as quite different from the warfare in other genre works:

You know they’re adventure stories without being like Baen books which have nothing but war stories in the U.S. – it’s violence – it’s just dirty! It’s pornography of violence I think. I can’t stand it. There’s too much of the heads rolling and guns bursting you know. It’s not my stick.

Harrison was an unabashed liberal and in these highly-polarized times his virtual father-son relationship with editor John W. Campbell is almost unfathomable given their irreconcilable political views. Yet it was Harrison who edited John W. Campbell: Collected Editorials from Analog, two volumes of The Astounding-Analog Reader, and The John W. Campbell Memorial Anthology. He told an interviewer in 1997 —

I was the very opposite of him politically in every way but he never dictated, It was easy to sell him a series, hard to sell him a short story. If he didn’t like a short story, he threw it out. But a serial, novel length thing, he knew what it was going to be like from the very beginning. And if he did not like it, he didn’t put it in. But he would allow you the freedom to do whatever you want. He might argue with you, but he wouldn’t correct you….

I worked with him, in a sense collaborated with him. When I gave him an outline for Deathworld, my first novel, he wrote me a five page letter of [pause] not telling me what to do but expatiating on my ideas. You didn’t have to follow him. He never told you to, “do this.” In a sense, all my novels, the first five or six, are a sort of collaboration with John….

There was a lot of give and take. Poul Anderson once said that having lunch with John Campbell was like throwing man-hole covers at each other, you know KLANG, CRASH, BANG.

The movie Soylent Green (1973) was based on Harrison’s novel Make Room! Make Room! (1966), elevating it as his most recognizable work. Considering Harrison’s stated dislike for Stanley R. Greenberg’s script, it’s either ironic or unfair that Soylent Green was also the only item of Harrison’s career to win a major award, a 1974 Nebula.

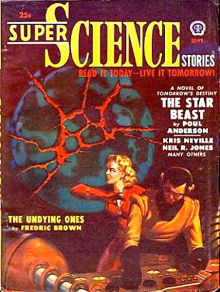

Harrison got his start in the professional sf field not as a writer but as an artist for EC Comics. Then for several years he was the main writer of the Flash Gordon newspaper comic strip.

Among his other achievements, Harrison co-edited nine editions of the Best SF annual with Brian Aldiss, spanning 1967-1975.

A fan of SF beginning in 1938 at the age of 13, Harrison co-founded the Queens chapter of the Science Fiction League. Later, as a pro writer in New York, he was part of the Hydra Club — and may well be somewhere in the LIFE magazine group photo (1950).

He also helped found World SF, primarily organized to hold regular meetings of sf professionals all over the world to which Soviet bloc and Chinese sf writers could be invited, facilitating their ability to travel to the west.

Another friend impressed me even more with the news that my favorite prozine had experimented with a large format during WWII — collectors called them “bedsheet Astoundings” — and had briefly revived the format (as Analog) just a few years before. I found them for sale in used bookstores and soon owned a copy of the most dramatic prozine cover ever, John Schoenherr’s depiction of a sandworm for the March 1965 Analog.

Another friend impressed me even more with the news that my favorite prozine had experimented with a large format during WWII — collectors called them “bedsheet Astoundings” — and had briefly revived the format (as Analog) just a few years before. I found them for sale in used bookstores and soon owned a copy of the most dramatic prozine cover ever, John Schoenherr’s depiction of a sandworm for the March 1965 Analog.